По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

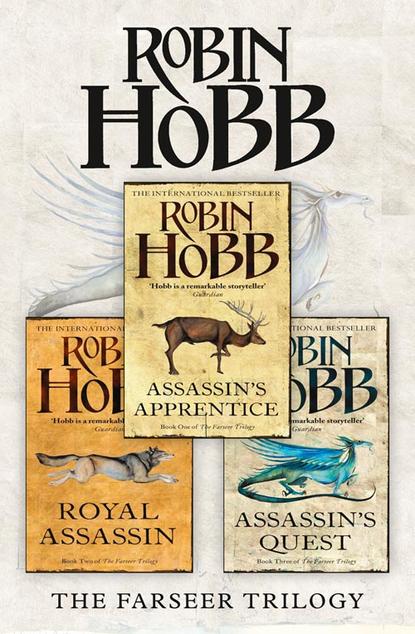

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘He has become his father’s favourite,’ Chade growled. ‘Shrewd has done nothing but spoil him since the Queen died. He tries to buy the boy’s heart with gifts, now that his mother is no longer around to claim his allegiance. And Regal takes full advantage. He speaks only what the old man loves to hear. And Shrewd gives him too much rein. He lets him wander about, squandering coin on useless visits to Farrow and Tilth, where his mother’s people fill Regal with ideas of his self-importance. The boy should be kept at home and made to give some account for how he spends his time. And the King’s money. What he spends gallivanting about would have outfitted a warship.’ And then, suddenly annoyed, ‘That’s too hot! You’ll lose it, fish it out quickly.’

But his words came too late, for the crucible cracked with a noise like breaking ice and its contents filled Chade’s tower room with an acrid smoke that brought all lessons and talk to an end for that night.

I was not soon summoned again. My other lessons went on, but I missed Chade as the weeks passed and he did not call for me. I knew he was not displeased with me, but only preoccupied. When, idle one day, I pushed my awareness towards him, I felt only secrecy and discordance. And a wallop to the back of my head when Burrich caught me at it.

‘Stop it,’ he hissed, and ignored my studied look of shocked innocence. He glanced about the stall I was mucking out as if he expected to find a dog or cat lurking.

‘There’s nothing here!’ he exclaimed.

‘Just manure and straw,’ I agreed, rubbing the back of my head.

‘Then what were you doing?’

‘Daydreaming,’ I muttered. ‘That was all.’

‘You can’t fool me, Fitz,’ he growled. ‘And I won’t have it. Not in my stables. You won’t pervert my beasts that way. Or degrade Chivalry’s blood. Mind what I’ve told you.’

I clenched my jaws and lowered my eyes and kept on working. After a time I heard him sigh and move away. I went on raking, inwardly seething and resolving never to let Burrich come up on me unawares again.

The rest of that summer was such a whirlpool of events that I find it hard to recall their progression. Overnight, the very feeling of the air seemed to change. When I went into town, all of the talk was of fortifications and readiness. Only two more towns were Forged that summer, but it seemed a hundred, for the stories of it were repeated and enlarged from lip to lip.

‘Until it seems as if that is all folk talk about any more,’ Molly complained to me.

We were walking on Long Beach, in the light of the summer evening sun. The wind off the water was a welcome bit of cool after a muggy day. Burrich had been called away to Springmouth to see if he could work out why all the cattle there were developing huge hide sores. It meant no morning lessons for me, but many, many more chores with the horses and hounds in his absence, especially as Cob had gone to Turlake with Regal, to manage his horses and hounds for a summer hunt.

But the opposite weight of the balance was that my evenings were less supervised, and I had more time to visit town.

My evening walks with Molly were almost a routine now. Her father’s health was failing and he scarcely needed to drink to fall into an early and deep sleep each night. Molly would pack a bit of cheese and sausage for us, or a small loaf and some smoked fish, and we would take a basket and a bottle of cheap wine and walk out down the beach to the breakwater rocks. There we would sit on the rocks as they gave up the last heat of the day, and Molly would tell me about her day’s work and the day’s gossip and I would listen. Sometimes our elbows bumped as we walked.

‘Sara, the butcher’s daughter, told me that she positively yearns for winter to come. The winds and ice will beat the Red Ships back to their own shores for a bit, and give us a rest from fear, she says. But then Kelty up and says that maybe we’ll be able to stop fearing more Forging, but that we’ll still have to fear the Forged folk that are loose in our land. Rumour says that some from Forge have left there, now that there’s nothing left for them to steal, and that they travel about as bandits, robbing travellers.’

‘I doubt it. More than likely it’s other folk doing the robbing, but trying to pass themselves off as Forged folk to send revenge looking elsewhere. Forged folk don’t have enough kinship left in them to be a band of anything,’ I contradicted her lazily. I was looking out across the bay, my eyes almost closed against the glare of the sun on the water. I didn’t have to look at Molly to feel her there beside me. It was an interesting tension, one I didn’t fully understand. She was sixteen, and I about fourteen, and those two years loomed between us like an unsurmountable wall. Yet she always made time for me, and seemed to enjoy my company. She seemed as aware of me as I was of her. But if I quested toward her at all, she would draw back, halting to shake a pebble from her shoe or suddenly speaking of her father’s illness and how much he needed her. Yet if I drew my sensings back from that tension, she became uncertain and shyer of speech, and would try to look at my face and the set of my mouth and eyes. I didn’t understand it, but it was as if we held a string taut between us. But now I heard an edge of annoyance in her speech.

‘Oh. I see. And you know so much of Forged folk, do you, more than those who have been robbed by them?’

Her tart words caught me off-balance and it was a moment or two before I could speak. Molly knew nothing of Chade and me, let alone of my side trip with him to Forge. To her, I was an errand-boy for the keep, working for the stablemaster when I wasn’t fetching for the scribe, I couldn’t betray my first-hand knowledge, let alone how I had sensed what Forging was.

‘I’ve heard the talk of the guards, when they’re around the stables and kitchens at night. Soldiers like them have seen much of all kinds of folk, and they’re the ones who say that the Forged ones have no friendships, no family, no kinship ties at all left. Still, I suppose if one of them took to robbing travellers, others would copy him, and it would be almost the same as a band of robbers.’

‘Perhaps.’ She seemed mollified by my comments. ‘Look, let’s climb up there to eat.’

‘Up there’ was a shelf on the cliff’s edge rather than the breakwater. But I assented with a nod, and the next handful of minutes were spent in getting ourselves and our basket up there. It required more arduous climbing than our earlier expeditions had. I caught myself watching to see how Molly would manage her skirts, and taking opportunities to catch at her arm to balance her, or take her hand to help her up a steep bit while she kept hold of the basket. In a flash of insight I knew that Molly’s suggestion that we climb had been her way of manipulating the situation to cause this. We finally gained the ledge and sat, looking out over the water with her basket between us, and I was savouring my awareness of her awareness of me. It reminded me of the clubs of the Springfest jugglers as they handed them back and forth, back and forth, more and more and faster and faster. The silence lasted until a time when one of us had to speak. I looked at her, but she looked aside. She looked into the basket and said, ‘Oh, dandelion wine? I thought that wasn’t any good until after midwinter.’

‘It’s last year’s … it’s had a winter to age,’ I told her, and took it from her to work the cork loose with my knife. She watched me worry at it for a while, and then took it from me and, drawing her own slender sheath-knife, speared and twisted it out with a practised knack that I envied.

She caught my look and shrugged. ‘I’ve been pulling corks for my father for as long as I can remember. It used to be because he was too drunk. Now he doesn’t have the strength in his hands any more, even when he’s sober.’ Pain and bitterness mingled in her words.

‘Ah.’ I floundered for a more pleasant topic. ‘Look, the Rainmaiden.’ I pointed out over the water to a sleek-hulled ship coming into the harbour under oars. ‘I’ve always thought her the most beautiful ship in the harbour.’

‘She’s been on patrol: The cloth merchants took up a collection. Almost every merchant in town contributed. Even I, although all I could spare was candles for her lanterns. She’s manned with fighters now, and escorts the ships between here and Highdowns. The Greenspray meets them there and takes them further up the coast.’

‘I hadn’t heard that.’ And it surprised me that I had not heard such a thing up in the keep itself. My heart sank in me, that even Buckkeep Town was taking measures independent of the King’s advice or consent. I said as much.

‘Well, folk have to do whatever they can if all King Shrewd is going to do is click his tongue and frown about it. It’s well enough for him to bid us to be strong, when he sits secure up in his castle. It isn’t as if his son or brother or little girl will be Forged.’

It shamed me that I could think of nothing to say in my King’s defence. And shame stung me to say, ‘Well, you’re almost as safe as the King himself, living here below in Buckkeep Town.’

Molly looked at me levelly. ‘I had a cousin, apprenticed out in Forge Town.’ She paused, then said carefully, ‘Will you think me cold when I say that we were relieved to hear he had only been killed? It was uncertain for a week or so, but finally we had word from one who had seen him die. And my father and I were both relieved. We could grieve, knowing that his life was simply over and we would miss him. We no longer had to wonder if he were still alive and behaving like a beast, causing misery to others and shame to himself.’

I was silent for a bit. Then, ‘I’m sorry.’ It seemed inadequate, and I reached out to pat her motionless hand. For a second it was almost as if I couldn’t feel her there, as if her pain had shocked her into an emotional numbness the equal of a Forged one. But then she sighed and I felt her presence again beside me. ‘You know,’ I ventured, ‘perhaps the King himself does not know what to do either. Perhaps he is at as great a loss for a solution as we are.’

‘He is the King!’ Molly protested. ‘And named Shrewd to be shrewd. Folk are saying now he but holds back to keep the strings of his purse tight. Why should he pay out of his hoard, when desperate merchants will hire mercenaries of their own? But, enough of this …’ she held up a hand to stop my words. ‘This is not why we came out here into the peace and coolness, to talk of politics and fears. Tell me instead of what you’ve been doing. Has the speckled bitch had her pups yet?’

And so we spoke of other things, of Motley’s puppies and of the wrong stallion getting at a mare in season, and then she told me of gathering greencones to scent her candles and picking blackberries, and how busy she would be for the next week, trying to make blackberry preserves for the winter while still tending the shop and making candles.

We talked and ate and drank and watched the late sun of summer as it lingered low on the horizon, almost but not quite setting. I felt the tension as a pleasant thing between us, as both a suspension and a wonder. I viewed it as an extension of my strange new sense, and so I marvelled that Molly seemed to feel and react to it as well. I wanted to speak to her about it, to ask her if she was aware of other folk in a similar way. But I feared that if I asked her, I might reveal myself as I had to Chade, or that she might be disgusted by it as I knew Burrich would be. So I smiled, and we talked, and I kept my thoughts to myself.

I walked her home through the quiet streets and bid her good night at the door of the chandlery. She paused a moment, as if thinking of something else she wanted to say, but then gave me only a quizzical look and a softly muttered, ‘Good night, Newboy.’

I took myself home under a deeply blue sky pierced by bright stars, past the sentries at their eternal dice game and up to the stables. I made a quick round of the stalls, but all was calm and well there, even with the new puppies. I noticed two strange horses in one of the paddocks, and one lady’s palfrey had been stabled. Some visiting noblewoman come to court, I decided. I wondered what had brought her here at the end of the summer, and admired the quality of her horses. Then I left the stables and headed up to the keep.

By habit my path took me through the kitchens. Cook was familiar with the appetites of stable-boys and men-at-arms, and knew that regular meals did not always suffice to keep one full. Especially lately I had found myself getting hungry at all hours, while Mistress Hasty had recently declared that if I didn’t stop growing so rapidly, I should have to wrap myself in barkcloth like a wild man, for she had no idea how to keep me looking as if my clothes fitted. I was already thinking of the big earthenware bowl that Cook kept full of soft biscuits and covered with a cloth, and of a certain wheel of especially sharp cheese, and how well both would go with some ale, when I entered the kitchen door.

There was a woman at the table. She had been eating an apple and cheese, but at the sight of me coming in the door, she sprang up and put her hand over her heart as if she thought I were the Pocked Man himself. I paused. ‘I did not mean to startle you, lady. I was merely hungry, and thought to get myself some food. Will it bother you if I stay?’

The lady slowly sank back into her seat. I wondered privately what someone of her rank was doing alone in the kitchen at night, for her high birth was something that could not be disguised by the simple cream robe she wore or the weariness in her face. This, undoubtedly, was the rider of the palfrey in the stable, and not some lady’s maid. If she had awakened hungry at night, why hadn’t she simply bestirred a servant to fetch something for her?

Her hand rose from clutching at her breast to pat at her lips, as if to steady her uneven breath. When she spoke, her voice was well-modulated, almost musical. ‘I would not keep you from your food. I was simply a bit startled. You … came in so suddenly.’

‘My thanks, lady.’

I moved around the big kitchen, from ale cask to cheese to bread, but everywhere I went, her eyes followed me. Her food lay ignored on the table where she had dropped it when I came in. I turned from pouring myself a mug of ale to find her eyes wide upon me. Instantly she dropped them away. Her mouth worked, but she said nothing.

‘May I do something for you?’ I asked politely. ‘Help you find something? Would you care for some ale?’

‘If you would be so kind.’ She said the words softly. I brought her the mug I had just filled and set it on the table before her. She drew back when I came near her, as if I carried some contagion. I wondered if I smelled bad from my stable work earlier. I decided not, for Molly would have surely mentioned it. Molly was ever frank with me about such things.

I drew another mug for myself, and then, looking about, decided it would be better to carry my food up to my room. The lady’s whole attitude bespoke her uneasiness at my presence. But as I was struggling to balance biscuits and cheese and mug, she gestured at the bench opposite her. ‘Sit down,’ she told me, as if she had read my thoughts. ‘It is not right I should scare you away from your meal.’

Her tone was neither command nor invitation, but something in between. I took the seat she indicated, my ale slopping over a bit as I juggled food and mug into place. I felt her eyes on me as I sat. Her own food remained ignored before her. I ducked my head to avoid that gaze, and ate quickly, as furtively as a rat in a corner who suspects a cat is behind the door, waiting. She did not stare rudely, but openly watched me, with the sort of observation that made my hands clumsy, and led to my acute awareness that I had just unthinkingly wiped my mouth on the back of my sleeve.

I could think of nothing to say, and yet the silence jabbed at me. The biscuit seemed dry in my mouth, making me cough, and when I tried to wash it down with ale, I choked. Her eyebrows twitched, her mouth set more firmly. Even with my eyes lowered to my plate, I felt her gaze. I rushed through my food, wanting only to escape her hazel eyes and straight silent mouth. I pushed the last hunks of bread and cheese into my mouth and stood up quickly, bumping against the table and almost knocking the bench over in my haste. I headed toward the door, then remembered Burrich’s instructions about excusing oneself from a lady’s presence. I swallowed my half-chewed mouthful.

‘Good night to you, lady,’ I muttered, thinking the words not quite right, but unable to summon better. I crabbed toward the door.

‘Wait,’ she said, and when I paused, she asked, ‘Do you sleep upstairs, or out in the stables?’

‘Both. Sometimes. I mean, either. Ah, good night, then, lady.’ I turned and all but fled. I was halfway up the stairs before I wondered at the strangeness of her question. It was only when I went to undress for bed that I realized I still gripped my empty ale mug. I went to sleep, feeling a fool, and wondering why.