По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

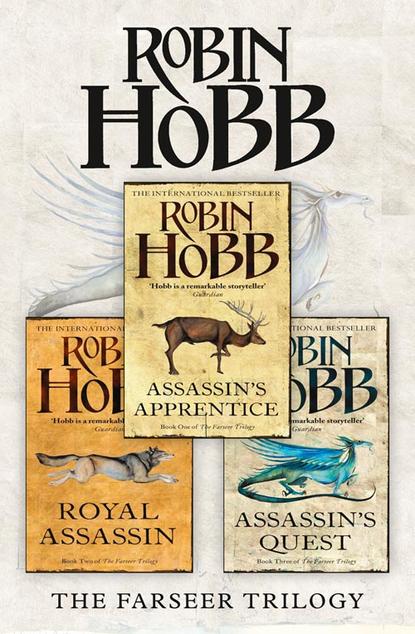

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A dozen questions rose to my mind. Chade saw the expression on my face, for he held up a quelling hand. ‘Not now. That’s as much as you need to know right now. In fact, more than you need to know. But I was surprised by your revelation. It’s not like me to tell secrets not my own. If the Fool wants you to know more, he can speak for himself. But, I seem to recall we were discussing Galen.’

I sank back in my chair with a sigh. ‘Galen. So he is unpleasant to those who cannot challenge it, dresses well and eats alone. What else do I need to know, Chade? I’ve had strict teachers, and I’ve had unpleasant ones. I think I’ll learn to deal with him.’

‘You’d better.’ Chade was deadly earnest. ‘Because he hates you. He hates you more than he loved your father. The depth of emotion he felt for your father unnerved me. No man, not even a prince, merits such blind devotion, especially not so suddenly. And you he hates, with even more intensity. It frightens me.’

Something in Chade’s tone brought a sick chill stalking up from my stomach. I felt an uneasiness that almost made me sick. ‘How do you know?’ I demanded.

‘Because he told Shrewd so when Shrewd directed him to include you among his pupils. “Does not this bastard have to learn his place? Does he not have to be content with what you have decreed for him?” Then he refused to teach you.’

‘He refused?’

‘I told you. But Shrewd was adamant. And he is King, and Galen must obey him now, for all that he was a Queen’s man. So Galen relented and said he would attempt to teach you. You will meet with him each day. Beginning a month from now. You are Patience’s until then.’

‘Where?’

‘There is a tower top, called the Queen’s Garden. You will be admitted there.’ Chade paused, as if wanting to warn me, but not wishing to scare me. ‘Be careful,’ he said at last, ‘for within the walls of the Garden, I have no influence. I am blind there.’

It was a strange warning, and one I took to heart.

THIRTEEN (#ulink_f438f480-b73c-59f0-b397-eec12d2a04cf)

Smithy (#ulink_f438f480-b73c-59f0-b397-eec12d2a04cf)

The Lady Patience established her eccentricity at an early age. As a small child, her nursemaids found her stubbornly independent, and yet lacking the common sense to take care of herself. One remarked, ‘She would go all day with her laces undone because she could not tie them herself, yet would suffer no one to tie them for her.’ Before the age of ten, she had decided to eschew the traditional trainings befitting a girl of her rank, and instead interested herself in handicrafts that were very unlikely to prove useful: pottery, tattooing, the making of perfumes, and the growing and propagation of plants, especially foreign ones.

She did not scruple to absent herself for long hours from supervision. She preferred the woodlands and orchards to her mother’s courtyards and gardens. One would have thought this would produce a hardy and practical child. Nothing could be further from the truth. She seemed to be constantly afflicted with rashes, scrapes and stings, was frequently lost, and never developed any sensible wariness toward man or beast.

Her education came largely from herself. She mastered reading and ciphering at an early age, and from that time studied any scroll, book or tablet that came her way with avaricious and indiscriminate interest. Tutors were frustrated by her distractable ways and frequent absences that seemed to affect not at all her ability to learn almost anything swiftly and well. Yet the application of such knowledge interested her not at all. Her head was full of fancies and imaginings, she substituted poetry and music for logic and manners, she expressed no interest at all in social introductions and coquettish skills.

And yet she married a prince, one who had courted her with a single-minded enthusiasm that was to be the first scandal to befall him.

‘Stand up straight!’

I stiffened.

‘Not like that! You look like a turkey, drawn out and waiting for the axe. Relax more. No, put your shoulders back, don’t hunch them. Do you always stand with your feet thrown out so?’

‘Lady, he is only a boy. They are always so, all angles and bones. Let him come in and be at ease.’

‘Oh, very well. Come in, then.’

I nodded my gratitude to a round-faced serving-woman who dimpled a smile at me in return. She gestured me toward a pewbench so bedecked with pillows and shawls that there was scarcely room left to sit. I perched on the edge of it and surveyed Lady Patience’s chamber.

It was worse than Chade’s. I would have thought it the clutter of years if I had not known that she had only recently arrived. Even a complete inventory of the room could not have described it, for it was the juxtaposition of objects that made them remarkable. A feather fan, a fencing glove and a bundle of cattails were all vased in a well-worn boot. A small black terrier with two fat puppies slept in a basket lined with a fur hood and some woollen stockings. A family of carved-ivory walruses perched on a tablet about horse-shoeing. But the dominant elements were the plants. There were fat puffs of greenery overflowing clay pots, teacups and goblets, and buckets of cuttings and cut-flowers, and vines spilling out of handleless mugs and cracked cups. Failures were evident in bare sticks poking up out of pots of earth. The plants perched and huddled together in every location that would catch morning or afternoon sun from the windows. The effect was like a garden spilling in the windows and growing up around the clutter in the room.

‘He’s probably hungry, too, isn’t he, Lacey? I’ve heard that about boys. I think there’s some cheese and biscuits on the stand by my bed. Fetch them for him, would you, dear?’

Lady Patience stood slightly more than arm’s distance away from me as she spoke past me to her lady.

‘I’m not hungry, really, thank you,’ I blurted out before Lacey could lumber to her feet. ‘I’m here because I was told … to make myself available to you, in the mornings, for as long as you wanted me.’

That was a careful rephrasing. What King Shrewd had actually said to me was, ‘Go to her chambers each morning, and do whatever it is she thinks you ought to be doing so that she leaves me alone. And keep doing it until she is as weary of you as I am of her.’ His bluntness had astounded me, for I had never seen him so beleaguered as that day. Verity came in the door of the chamber as I was scuttling out, and he, too, looked much the worse for wear. Both men spoke and moved as if suffering from too much wine the night before, and yet I had seen them both at table last night, and there had been a marked lack of either merriness or wine. Verity tousled my head as I went past him. ‘More like his father every day,’ he remarked to a scowling Regal behind him. Regal glared at me as he entered the King’s chamber and loudly closed the door behind him.

So here I was, in my lady’s chamber, and she was skirting about me and talking past me as if I were an animal that might suddenly strike out at her or soil the carpets. I could tell that it afforded Lacey much amusement.

‘Yes. I already knew that, you see, because I was the one who had asked the King that you be sent here,’ Lady Patience explained carefully to me.

‘Yes, ma’am.’ I shifted on my bit of seat-space and tried to look intelligent and well-mannered. Recalling the earlier times we had met, I could scarcely blame her for treating me like a dolt.

A silence fell. I looked around at things in the room. Lady Patience looked toward a window. Lacey sat and smirked to herself and pretended to be tatting lace.

‘Oh. Here.’ Swift as a diving hawk, Lady Patience stooped down and seized the black terrier pup by the scruff of the neck. He yelped in surprise, and his mother looked up in annoyance as Lady Patience thrust him into my arms. ‘This one’s for you. He’s yours now. Every boy should have a pet.’

I caught the squirming puppy and managed to support his body before she let go of him. ‘Or maybe you’d rather have a bird? I have a cage of finches in my bedchamber. You could have one of them, if you’d rather.’

‘Uh, no. A puppy’s fine. A puppy is wonderful.’ The second half of the statement was made to the pup. My instinctive response to his high-pitched yi-yi-yi had been to quest out to him with calm. His mother had sensed my contact with him, and approved. She settled back into her basket with the white pup with blithe unconcern. The puppy looked up at me and met my eyes directly. This, in my experience, was rather unusual. Most dogs avoided prolonged direct eye-contact. But also unusual was his awareness. I knew from surreptitious experiments in the stable that most puppies his age had little more than fuzzy self-awareness, and were mostly turned to mother and milk and immediate needs. This little fellow had a solidly-established identity within himself, and a deep interest in all that was going on around him. He liked Lacey, who fed him bits of meat, and was wary of Patience, not because she was cruel, but because she stumbled over him and kept putting him back in the basket each time he laboriously clambered out. He thought I smelled very exciting, and the scents of horses and birds and other dogs were like colours in my mind, images of things that as yet had no shape or reality for him, but that he nonetheless found fascinating. I imaged the scents for him and he climbed my chest, wriggling, sniffing and licking me in his excitement. Take me, show me, take me.

‘… even listening?’

I winced, expecting a rap from Burrich, then came back to awareness of where I was and of the small woman standing before me with her hands on her hips.

‘I think something’s wrong with him,’ she observed abruptly to Lacey. ‘Did you see how he was sitting there, staring at the puppy? I thought he was about to go off into some sort of fit.’

Lacey smiled benignly and went on with her tatting. ‘Fair reminded me of you, my lady, when you start pottering about with your leaves and bits of plants and end up staring at the dirt.’

‘Well,’ said Patience, clearly displeased. ‘It is quite one thing for an adult to be pensive,’ she observed firmly. ‘And another for a boy to stand about looking daft.’

Later, I promised the pup. ‘I’m sorry,’ I said, and tried to look repentant. ‘I was just distracted by the puppy.’ He had cuddled into the crook of my arm and was casually chewing the edge of my jerkin. It is difficult to explain what I felt. I needed to pay attention to Lady Patience, but this small being snuggled against me was radiating delight and contentment. It is a heady thing to be suddenly proclaimed the centre of someone’s world, even if that someone is an eight-week-old puppy. It made me realize how profoundly alone I had felt, and for how long. ‘Thank you,’ I said, and even I was surprised at the gratitude in my voice. ‘Thank you very much.’

‘It’s just a puppy,’ Lady Patience said, and to my surprise she looked almost ashamed. She turned aside and stared out the window. The puppy licked his nose and closed his eyes. Warm. Sleep. ‘Tell me about yourself,’ she demanded abruptly.

It took me aback. ‘What would you like to know, lady?’

She made a small, frustrated gesture. ‘What do you do each day? What have you been taught?’

So I attempted to tell her, but I could see that it didn’t satisfy her. She folded her lips tightly at each mention of Burrich’s name. She wasn’t impressed with any of my martial training. Of Chade, I could say nothing. She nodded in grudging approval of my study of languages, writing and ciphering.

‘Well,’ she interrupted suddenly. ‘At least you’re not totally ignorant. If you can read, you can learn anything. If you’ve a will to. Have you a will to learn?’

‘I suppose so.’ It was a lukewarm answer, but I was beginning to feel badgered. Not even the gift of the puppy could outweigh her belittlement of my learning.

‘I suppose you will learn, then. For I have a will that you will, even if you do not yet.’ She was suddenly stern, in a shifting of attitude that left me bewildered. ‘And what do they call you, boy?’

The question again. ‘Boy is fine,’ I muttered. The sleeping puppy in my arms whimpered in agitation. I forced myself to be calm for him.

I had the satisfaction of seeing a stricken look flit briefly across Patience’s face. ‘I shall call you, oh, Thomas. Tom for everyday. Does that suit you?’

‘I suppose so,’ I said deliberately. Burrich gave more thought to naming a dog than that. We had no Blackies or Spots in the stables. Burrich named each beast as if they were royalty, with names that described them or traits he aspired to for them. Even Sooty’s name masked a gentle fire I had come to respect. But this woman named me Tom after no more than an indrawn breath. I looked down so that she couldn’t see my eyes.