По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

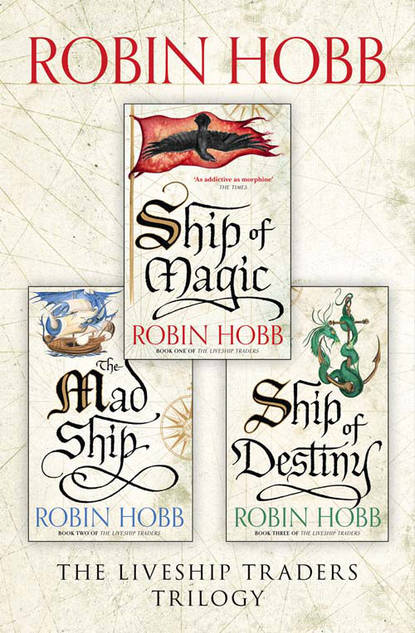

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Damn. And the night started out so well.’

She trudged down the street with him leaning heavily on her shoulder. At the corner of a shuttered mercantile store she stopped to get her bearings. The whole town was black as pitch and the cold rain running down her face didn’t help any.

‘Stop a minute, Althea. I’ve got to piss.’

‘Athel,’ she reminded him wearily. His modesty consisted of stumbling two steps away as he fumbled at his pants.

‘Sorry,’ he said gruffly a few moments later.

‘It’s all right,’ she told him tolerantly. ‘You’re still drunk.’

‘Not drunk,’ he insisted. He put a hand on her shoulder again. ‘There was something in the beer, I think. No, I’m sure of it. I’d have probably tasted it, but for the cindin.’

‘You chew cindin?’ Althea asked incredulously. ‘You?’

‘Sometimes,’ Brashen said defensively. ‘Not often. And I haven’t in a long time.’

‘My father always said it’s killed more sailors than bad weather,’ Althea told him sourly. Her head was pounding.

‘Probably,’ Brashen agreed. As they passed beyond the buildings and came to the docks he offered, ‘You should try it sometime, though. Nothing like it for setting a man’s problems aside.’

‘Right.’ He seemed to be getting wobblier. She put her arm around his waist. ‘Not far to go now.’

‘I know. Hey. What happened back there? In the tavern?’

She wanted so badly to be angry then but found she didn’t have the energy. It was almost funny. ‘You nearly got crimped. I’ll tell you about it tomorrow.’

‘Oh.’ A long silence followed. The wind died down for a few breaths. ‘Hey. I was thinking about you earlier. About what you should do. You should go north.’

She shook her head in the darkness. ‘No more slaughter-boats for me after this. Not unless I have to.’

‘No, no. That’s not what I mean. Way north, and west. Up past Chalced, to the Duchies. Up there, the ships are smaller. And they don’t care if you’re a man or a woman, so long as you work hard. That’s what I’ve heard anyway. Up there, women captain ships, and sometimes the whole damned crew are women.’

‘Barbarian women,’ Althea pointed out. ‘They’re more related to the Out Islanders than they are to us, and from what I’ve heard, they spend most of their time trying to kill each other off. Brashen, most of them can’t even read. They get married in front of rocks, Sa help us all.’

‘Witness stones,’ he corrected her.

‘My father used to trade up there, before they had their war,’ she went on doggedly. They were out on the docks now, and the wind suddenly gusted up with an energy that nearly pushed her down. ‘He said,’ she grunted as she kept Brashen to his feet, ‘that they were more barbaric than the Chalcedeans. That half their buildings didn’t even have glass windows.’

‘That’s on the coast,’ he corrected her doggedly. ‘I’ve heard that inland, some of the cities are truly magnificent.’

‘I’d be on the coast,’ she reminded him crankily. ‘Here’s the Reaper. Mind your step.’

The Reaper was tied to the dock, shifting restlessly against her hemp camels as both wind and waves nudged at her. Althea had expected to have a difficult time getting him up the gangplank, but Brashen went up it surprisingly well. Once aboard, he stood clear of her. ‘Well. Get some sleep, boy. We sail early.’

‘Yessir,’ she replied gratefully. She still felt sick and woozy. Now that she was back aboard and so close to her bed, she was even more tired. She turned and trudged away to the hatch. Once below she found some few of the crew still awake and sitting around a dim lantern.

‘What happened to you?’ Reller greeted her.

‘Crimpers,’ she said succinctly. ‘They made a try for Brashen and me. But we got clear of them. They found the hunter off the Tern, too. And a couple of others, I guess.’

‘Sa’s balls!’ the man swore. ‘Was the skipper from the Jolly Gal in on it?’

‘Don’t know,’ she said wearily. ‘But Pag was for sure, and his girl. The beer was drugged. I’ll never go in his tavern again.’

‘Damn. No wonder Jord’s sleeping so sound, he got the dose that was meant for you. Well, I’m heading over to the Tern, hear what that hunter has to say,’ Reller declared.

‘Me, too.’

Like magic, the men who were even partially awake rose and flocked off to hear the gossip. Althea hoped the tale would be well embroidered for them. For herself, she wanted only her hammock and to be under sail again.

It took him four tries to light the lantern. When the wick finally burned, he lowered the glass carefully and sat down on his bunk. After a moment he rose, to go to the small looking-glass fastened to the wall. He pulled down his lower lip and looked at it. Damn. He’d be lucky if the burns didn’t ulcerate. He’d all but forgotten that aspect of cindin. He sat down heavily on his bunk again and began to peel his coat off. It was then he realized the left cuff of his coat was soaked with blood as well as rain. He stared at it for a time, then gingerly felt the back of his head. No. A lump, but no blood. The blood wasn’t his. He patted his fingers against the patch of it. Still wet, still red. Althea? he wondered groggily. Whatever they had put in the beer was still fogging his brain. Althea, yes. Hadn’t she told him she’d been hit on the head? Damn her, why hadn’t she said she was bleeding? With the sigh of a deeply wronged man, he pulled his coat on again and went back out into the storm.

The forecastle was as dark and smelly as he remembered it. He shook two men awake before he found one coherent enough to point out her bunking spot. It was up in a corner a rat wouldn’t have room to turn around in. He groped his way there by the stub of a candle and then shook her awake despite curses and protests. ‘Come to my cabin, boy, and get your head stitched and stop your snivelling,’ he ordered her. ‘I won’t have you lying abed and useless for a week with a fever. Lively, now. I haven’t all night.’

He tried to look irritable and not anxious as she followed him out of the hold and up onto the deck and then into his cabin. Even in the candle’s dimness, he could see how pale she was, and how her hair was crusted with blood. As she followed him into his tiny chamber, he barked at her, ‘Shut the door! I don’t care to have the whole night’s storm blow through here.’ She complied with a sort of leaden obedience. The moment it was closed he sprang past her to latch it. He turned, seized her by the shoulders, and resisted the urge to shake her. Instead he sat her firmly on his bunk. ‘What is the matter with you?’ he hissed as he hung his coat on the peg. ‘Why didn’t you tell me you were hurt?’

She had, he knew, and half-expected that to be her reply. Instead she just raised a hand to her head and said vaguely, ‘I was just so tired…’

He cursed the small confines of his room as he stepped over her feet to reach the medicine chest. He opened it and picked through it, and then tossed his selections on the bunk beside her. He moved the lantern a bit closer; it was still too dim to see clearly. She winced as his fingers walked over her scalp, trying to part her thick dark hair and find the source of all the blood. His fingers were wet with it; it was still bleeding sluggishly. Well, scalp wounds always bled a lot. He knew that, it should not worry him. But it did, as did the unfocused look to her eyes.

‘I’m going to have to cut some of your hair away,’ he warned her, expecting a protest.

‘If you must.’

He looked at her more closely. ‘How many times did you get hit?’

‘Twice. I think.’

‘Tell me about it. Tell me everything you can remember about what happened tonight.’

And so she spoke, in drifting sentences, while he used scissors to cut her hair close to the scalp near the wound. Her story did not make him proud of his quick wits. Put together with what he knew of the evening, it was clear that both he and Althea had been targeted to fill out the Jolly Gal’s crew. It was only the sheerest luck that he was not chained up in her hold even now.

The split he bared in her scalp was as long as his little finger and gaping open from the pull of her queue. Even after he cut the hair around it to short stubble and cleared the clotted strands away, it still oozed blood. He blotted it away with a rag. ‘I’ll need to sew this shut,’ he told her. He tried to push away both the wooziness from whatever had been in his beer and his queasiness at the thought of pushing a needle through her scalp. Luckily Althea seemed even more beclouded than he was. Whatever the crimpers had put in the beer worked well.

By the lantern’s shifting yellow light, he threaded a fine strand of gut through a curved needle. It felt tiny in his calloused fingers, and slippery. Well, it couldn’t be that much different from patching clothes and sewing canvas, could it? He’d done that for years. ‘Sit still,’ he told her needlessly. Gingerly he set the point of the needle to her scalp. He’d have to push it in shallowly to make it come up again. He put gentle pressure on the needle. Instead of piercing her skin, her scalp slid on her skull. He couldn’t get the needle to slide through.

A bit more pressure and Althea yelled, ‘Wah!’ and suddenly batted his hand away. ‘What are you doing?’ she demanded angrily, turning to glare up at him.

‘I told you. I’ve got to stitch this shut.’

‘Oh.’ A pause. ‘I wasn’t listening.’ She rubbed at her eyes, then reached back to touch her own scalp cautiously. ‘I suppose you do have to close it,’ she said ruefully. She squeezed her eyes shut, then opened them again. ‘I wish I could either pass out or wake up,’ she said woefully. ‘I just feel foggy. I hate it.’

‘Let me see what I have in here,’ he suggested. He knelt on one knee to rummage through the ship’s stores of medicines. ‘This stuff hasn’t been replenished in years,’ he grumbled to himself as Althea peered past his shoulder. ‘Half the containers are empty, the herbs that should be green or brown are grey, and some of the other stuff smells like mould.’

‘Maybe it’s supposed to smell like mould?’ Althea suggested.

‘I don’t know,’ he muttered.