По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

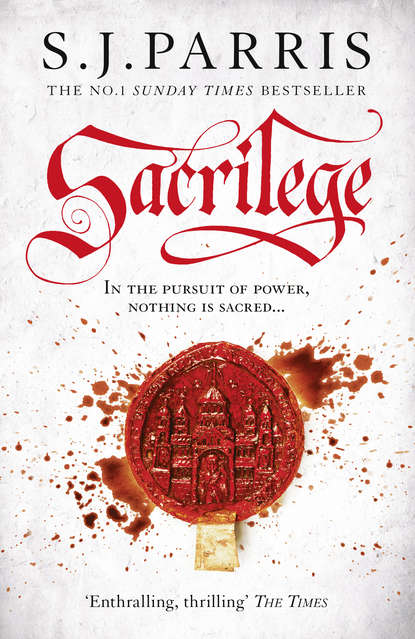

Sacrilege

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Tomorrow, then. And you take care of her,’ I added, just to let the boy know that I too had a vested interest. He took a step closer; he was taller than I, and drew himself up to emphasise this advantage.

‘We all want to keep her safe, monsieur. My family and friends risked everything to get her away from this place. Now you bring her back.’ He brought his face closer to mine and glared from beneath lowered brows, so fiercely it seemed he hoped I would burn up from the force of his eyes. ‘As if we did not have enough grief here already.’ Then he turned and disappeared inside the house, slamming the door behind him.

I looked around carefully at the windows of the neighbouring houses in case anyone had witnessed our exchange, but there was no obvious sign of movement. Even so, I felt distinctly uneasy as I led the horses back towards the main street, as if hostile eyes were following me, marking my steps.

I stabled the horses at the Cheker of Hope Inn, a great sprawling place that occupied most of the corner between the High Street, as I learned the main thoroughfare was called, and Mercery Lane, a smaller street that led towards the cathedral. The inn was one of the few that still seemed to attract a healthy trade; Sophia had recommended it because of its size; it was three storeys high, and built around a wide yard that often hosted performances by companies of travelling players. Despite my accent, the landlady – a heavily rouged woman in her forties – gave me an appreciative look when I secured the room; from the way her eyes travelled over me, I gathered she was pleased with more than the sight of the coins in my purse. I deflected her questions as politely as I could, hoping that here, with more travellers coming and going, I might enjoy greater anonymity than in the smaller places we had stayed in along the road, where everyone wants to know your business.

My stomach still felt dangerously unsettled – entirely my own fault, I suspected. The heat of the room during the previous night had brought on such a thirst that in desperation I had drunk some of the water left in a pitcher on the window-ledge for washing. Experience had taught me not to touch any water in England unless you have watched it come fresh from a spring or a well with your own eyes, but I had ignored good sense and now I was paying the price for it. With the horses safely stabled I was at liberty to explore the city on foot, and as I remembered noticing an apothecary’s sign along the High Street when we had ridden through the town, I decided to pay the shop a visit in the hope of purchasing something to ease my digestion before I attempted to introduce myself to Harry Robinson.

Over the door a painted sign showed the serpent coiled around a staff that denoted the apothecary’s trade; beside it the name Wm. Fitch. A bell chimed above the door as I entered and the front room was surprisingly cool inside, shaded from the heat of the day by the overhanging eaves, its small casements open to a vague breath of air from the street. I inhaled the sour-sweet smell that reminded me for a poignant moment of the distillery belonging to my friend Doctor Dee; a mixture of leaves and spices and bitter concoctions preserved in spirits. The apothecary was nowhere in sight so I closed the door behind me and called out a greeting as my gaze wandered over the shelves and cabinets lining the walls from floor to ceiling. Here great glass conical flasks containing potions and cordials in lurid colours vied for space beside earthenware jars of tinctures and pots stuffed with the raw ingredients for poultices and infusions, all balanced precariously alongside bunches of dried herbs, dog-eared books and other curiosities that may or may not have belonged to the man’s trade (on one shelf, a piccolo; on another, the skull of a ram). On the ware-bench in front of me, a pestle and mortar containing a greenish paste had been left as if in mid-preparation. Next to it stood a little brass balance, its weights scattered round about beside a quill and inkwell. I was peering up at one jar, trying to ascertain whether it really did contain a human finger, when the door at the back of the shop opened and a small, florid-faced man with receding hair appeared in a cloud of steam, wiping his hands on his smock. He flapped his hand as if to disperse the humid air.

‘Sorry about that,’ he said cheerfully, nodding towards the back room. ‘Had to check on my distillery. It’s like a Roman bath-house in there today.’ He paused to mop sweat from his forehead with a sleeve. ‘I’m a firm believer that steam purges the body of excess heat, though there are those who believe it has the opposite effect. Now, what can I do for you, sir? You have a choleric look about you –’ he waved a finger to indicate my face. ‘Something to balance the humours, perhaps?’

‘I’m just hot,’ I said, pushing my damp hair back from my face.

‘Ah, you are not English!’ he exclaimed, his eyes lighting up at the sound of my accent. ‘But not French either, I venture? Spanish, perhaps? Now, your Spaniards are naturally choleric, much more so than your Englishman, whose native condition tends towards the phlegmatic –’

‘Italian,’ I cut in. ‘And I have an upset stomach, though I think that has less to do with my birthplace than with drinking stale water. I was hoping you might have some infusion of mint leaves?’

‘My dear signor, I can do better than that,’ he beamed, grasping a little wooden ladder that leaned against the back shelves and moving it to the cabinet to my left. ‘I can offer you a most efficacious decoction of my own devising for disorders of the stomach, combining the benefits of mint leaf with hartshorn, syrup of violets, rosewater and syrup of red poppies. You will be thoroughly purged both upwards and downwards, I promise.’

‘It sounds tempting. But I’d prefer the mint leaves, I think.’

‘Really?’ He paused, a bottle of something thick and dark green held aloft. When I shook my head firmly, he replaced it on the shelf with a theatrical sigh. ‘Ah, you disappoint me, signor,’ he said, descending and shuffling his ladder to the right. His hand hovered over the shelves for a moment before plucking down a small packet, which he laid on the ware-bench and began to unwrap. ‘But you are right, it is a brave man or a desperate one who will experiment on himself with a stranger’s cures. I tell you what – if you are staying in Canterbury awhile and your problems do not resolve themselves, please do me the honour of coming back and at least giving my cordial a chance. I’ll do you a special price. Meanwhile you may ask around for testimony – I provide for some of the highest men in the city.’ He nodded enthusiastically. ‘Yes, including the physician to the Dean and the Mayor. Ask who you like – there’s not a man of means in these parts who doesn’t swear by Will Fitch’s remedies.’

I was beginning to like this Fitch, despite the fact that I had never met an apothecary who was not also a terrible fraud, and I suspected this one to be no different. If ever their remedies did work, it was entirely by lucky chance or guesswork; more often they knowingly sold wholly useless concoctions to the poor and credulous, who were too easily persuaded that the higher the price of a medicine, the more effective it would be.

‘The Dean’s own physician?’ I affected to look impressed. ‘No doubt aldermen and magistrates of the city too, eh?’

He puffed out his chest and patted it with the flat of his hand.

‘Doctor Sykes, he’s physician to them all – trained in Leipzig, you know – and he won’t buy his supplies anywhere else but my shop. Mind you,’ he added, with another heavy sigh, ‘there’s some things even he can’t cure. Our poor magistrate was horribly murdered not a month past and they have not appointed a new one yet, nor will they in time for the assizes. Mayor Fitzwalter has his hands full trying to do the job of two men preparing for the visit of the Queen’s Justice next week. You’ll have noticed the constables on every corner.’ I had not, but he did not wait for me to respond, shaking his head as if in sorrow at the state of the world. ‘Forgive me – I have a tendency to run on, and we are all much preoccupied with our civic affairs at the moment.’

‘I quite understand – murder is no small matter. Though I suppose that is a hazard of being a magistrate,’ I said, conversationally, as I watched him measure a quantity of dried leaves in his little scales. ‘The family of some felon he had convicted, out for revenge, I guess.’

‘Ah, not in this case,’ Fitch said, leaning closer over the bench, his eyes bright. ‘It was the wife – all of Canterbury knows it. She ran away the very same day and took a good deal of his money too.’

‘Really? What reason would she have to kill him?’

He put his head on one side and looked at me oddly, then gave a bleat of laughter.

‘From that remark, I deduce you have no wife, signor.’ He laughed again at his own joke, then shrugged. ‘They say she had a lover, but then they always like to say that. Pretty thing, she was. But she’s led the law a merry dance, I can tell you – they’ve had the hue and cry out for her since it happened, but they can’t find so much as a hair of her head. No, she’s long gone – over the water, if she’s any sense.’ He grinned, as if delighted by the audacity of the crime. ‘Now – do you want to take the leaves as they are or shall I make you up an infusion while you’re here? If you take it here, I’ll add a few fennel seeds – good against cramps of the gut. I have some spring water heating in the back room, it won’t take a moment.’

‘Thank you, I’d be grateful,’ I said, thinking that the man’s evident love of gossip could prove useful. He emptied the mint leaves into a small dish and disappeared through the door into the back of the shop. I wiped a trickle of sweat from my temples with the sleeve of my shirt and waited. Eventually he emerged carrying an earthenware beaker wrapped in a cloth.

‘Careful, it’s hot. That’s sixpence for the whole – I haven’t charged you for the fennel,’ he added.

I fished in my purse for the appropriate coin, which he examined closely, holding it up to the light.

‘No offence,’ he said, seeing me watching, ‘but we get all sorts of foreign types passing through from the Kentish ports, and I can’t trade with their coins. Not that I have anything against you lot, though many do. I like variety – keeps life interesting, doesn’t it?’ He tucked the coin into a moneybag at his belt. ‘I’d have liked to travel myself, if I’d had the means.’ He reached to a shelf under the bench and produced a large ledger, which he opened and thumbed through to the current page. Dipping the pen in the ink, he recorded the transaction meticulously. ‘May I take your name?’

‘My name?’

I must have reacted more suspiciously than I intended, because he looked taken aback.

‘Just for my shop records, signor. Helps me to remember what was sold and when, in case of any shortfall. I’ve a dreadful memory, you see.’ He tapped the side of his head and offered an encouraging smile.

‘Oh.’ I hesitated. ‘Savolino.’

Beside the amount received he dutifully inscribed ‘Savolino’, then glanced up and smiled again, as if to prove to me that this had had no ill effect.

‘Did they ever find the lover?’ I asked, sipping at the steaming cup. The concoction smelled refreshing and tasted pleasant enough, though the heat made more beads of sweat stand out on my face.

‘Well.’ He folded his arms and leaned against the bench as if settling in for the tale. ‘The son made a great noise, pointing his finger hither and yon, but nothing came of it. If he had a better character himself, his accusations might have stuck, but he’s been in so much trouble, that one, it was only ever his father’s money and position that kept him safe from the law. He’s not respected in the town. You couldn’t keep Master Nicholas Kingsley out of the Three Tuns long enough to notice what was going on under his own roof. Supposed to be studying the law himself, he was, up in London – well, that was a good joke. He was thrown out of his studies for drink and brawling. Ended up back here doing exactly the same at his father’s expense, God rest him.’

I drained the beaker. ‘It must have been a sore disappointment to his father.’

‘Well, they always were an odd family,’ Fitch said, squinting into the middle distance where spirals of dust eddied in the sunlight, as if trying to remember something.

‘How so?’

He shook his head dismissively. ‘Ah, goodwives’ gossip, most of it. His first wife was wealthy – she died of an ague, oh, ten years back. People whispered, as they always will, that he’d done her in, though as far as I know they had no reason to say so. But then maybe a year later he hired a maidservant, Sarah Garth, young girl from the town, and she’d not been there more than a few months when she took sick and died as well.’

‘Sickness is common enough everywhere, is it not?’ I tried to keep my voice casual.

‘Aye, of course, but folk found it strange that neither Sir Edward nor his son took ill with whatever she had. Still – in his defence, he brought in Doctor Sykes to treat the girl at his own expense. But they’ve taken no servants from that day to this, except their old housekeeper, Meg Turner. And there’s another thing.’ He leaned further across the bench and lowered his voice. ‘My late wife’s niece, Rebecca, she helps out Mistress Blunt on her stall at the bread market.’

He paused for effect; I bent towards him and nodded conspiratorially, as if I were quite familiar with the relationships of all these people.

‘Not more than six months past, Rebecca was asked to run an errand, take a package of bread out to Sir Edward Kingsley’s house – you know, the old priory out past the Northgate.’

‘I don’t know it, I’m afraid.’

‘Oh, he leased the prior’s house of St Gregory’s as was. Grand old building – the only bit of the priory left standing now, apart from the burial ground. Anyhow, she was walking through the graveyard to the door, and that’s where she heard it.’

‘Heard what?’

‘A dreadful cry.’ He gazed at me solemnly to let his words take effect. ‘She’ll swear to it – freeze your blood, she says. So frightened, she was, she dropped the bread and ran all the way back to the Blunts’ shop.’

My chest tightened; surely it could only have been Sophia, crying out as her husband administered one of his beatings. Again I pictured it, and the stoical, dull-eyed expression on her face when she related the story. I made an effort to unclench my jaw.

‘A woman screaming, was it?’

‘No.’ He held up a forefinger as if to admonish me. ‘That’s just it – she said it wasn’t like any human sound she’d heard. When she told the story, she was fairly shaking for pity. Well, of course, the graves are still there, so you can imagine how a young girl’s imagination runs wild. She said the noise came from beneath her feet, from the very graves themselves.’ He smiled indulgently. ‘Anyhow, she wouldn’t set foot near the place again. Mind you, nor will any other maid in Canterbury since Master Nicholas came back from London – he’ll do his best to grope any woman he can get his hands on, even in broad daylight.’ He frowned in disgust and I mirrored his expression in sympathy.

‘Though he is a rich man now, I suppose, with his father dead. Some woman might be glad of his attentions eventually,’ I ventured.

‘Ha! He’s not got a penny till his father’s last testament is sorted out,’ Fitch said, as if pleased by the justice of this. ‘Sir Edward had lately changed his bequests, but I understand nothing can be cleared up until the wife is found and tried, since she is one of the beneficiaries. Naturally, if she’s proved guilty, it’s all forfeit to Master Nicholas, but the law must take its course.’ He rolled his eyes; I smiled in solidarity. If there is one thing that can unite men from all walks of life and all countries, it is a shared contempt of lawyers.