По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

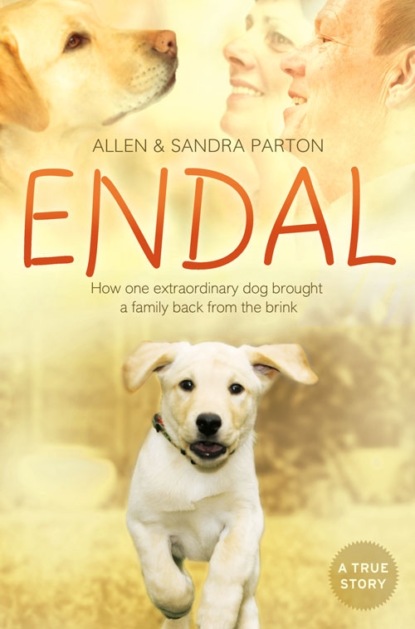

Endal: How one extraordinary dog brought a family back from the brink

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Are you sure?’ I asked, feeling hopeful. Surely he couldn’t be too bad if they were letting him out?

‘Why not? Just bring him back on Monday morning and he can see a consultant then. Have a nice family weekend together.’

The doctor smiled and I felt reassured. Everything was going to be all right. They wouldn’t let him home otherwise, would they?

A nurse and I helped Allen to get dressed and walk down to the car. On the way back to the house, I drove slowly and cautiously. I did all the talking, telling him about Valerie’s funeral and the children and everything that had been happening, but I got no response at all. He closed his eyes and I couldn’t even tell if he was listening, so after a while I stopped and drove in silence.

As we pulled into our street, I said, ‘The kids are really excited about seeing you. They’re at Julie’s but I said I’d go and get them as soon as we arrived.’ Julie was my wonderful next-door neighbour who had four kids of her own but was always happy to look after my two as well. ‘Two more don’t make any difference at all,’ she’d laugh.

Allen turned to look at me and I couldn’t read the expression in his eyes but he didn’t seem enthusiastic about seeing the kids. Maybe he wasn’t feeling well enough.

‘Why don’t we go in and get settled first?’ I suggested, and he nodded. He’d hardly spoken throughout the journey, and when he did his speech was very slow and indistinct and he was often lost for the most basic words.

We pulled into the driveway and I walked into the house behind him, noticing that he had an odd, rolling gait. He picked his right foot up high and flopped it down then pulled the other one through. It reminded me of the way the actor John Thaw walked. He’d had polio as a child and would pick his foot up and put it down with a strange precision. As a nurse, I’d always noticed that about him.

Allen plonked himself down on the sofa and sat looking around him.

‘Do you want something to drink?’ I asked.

‘Yeah.’

‘Do you want tea or coffee?’

He screwed up his face, unable to think. ‘The stuff that comes in bags,’ he slurred.

Tea, then.

At that moment there was a burst of squealing and running feet and the children erupted into the house.

‘Daddy!’ they shrieked, over the moon to see him. Zoe leaped on to his knee and Liam snuggled on to the sofa beside him.

‘Get off me!’ he snapped loudly as he pushed Zoe away. The look of bewilderment on her little face was heartbreaking.

‘Kids, Daddy’s not feeling very well. Don’t climb all over him.’

‘I’ve got a new train, Daddy,’ Liam said excitedly. They used to play together with his Playmobil train set.

‘And I’ve started ballet,’ Zoe joined in, not wanting to be left out. ‘And I’ve got a new dolly as well.’

‘Go away!’ Allen snarled, putting his hands over his ears.

They were devastated. Whenever Allen had come back from postings in the past, he’d burst in the door bringing them presents, swinging them in the air and tickling them. They just didn’t have a clue what had happened.

‘Daddy’s got a bad headache,’ I said gently. ‘You know what it’s like when your head hurts. Just leave him in peace for a little while and maybe he’ll play later.’

I sent them over to Julie’s for the afternoon, just telling her briefly that Allen wasn’t very well. When I got back, he was examining two tubes of cream he’d been given on prescription. He had a nasty rash on his feet and another one on his groin and they’d given him a different cream for each rash, but he couldn’t remember which was which. There was nothing written on the boxes and he was very anxious about it.

‘Which cream is which?’ he mumbled. ‘I don’t know.’

The old Allen would have made a joke out of it. He’d have said, ‘I’ll start by putting them on my feet because if my feet fall off that will be fine, but I don’t want the other bits to fall off.’

But he was incapable of joking now.

‘I’ll go to the pharmacy and ask them,’ I offered. ‘Let me just get your tea first.’

Two minutes later, as if I hadn’t spoken, Allen asked, ‘What about this cream for my feet? What am I going to do?’

It was like being with an old person who had Alzheimer’s. When I worked in a nursing home, some of the residents would ask the same question over and over again – usually: ‘When is my daughter coming? Why’s she not here yet?’ That weekend Allen asked me about his creams at least twenty times a day and he never seemed to hear the answers I gave.

I showed him the photos I’d had developed from a holiday we’d had in Singapore and Penang just a couple of months earlier, but there was no spark of recognition. He didn’t seem to remember us being there and I thought that was very worrying. He just looked at each one and handed it back to me without comment.

He didn’t seem to remember where anything was in the house either. I had to show him where his clothes were kept, where his shaving stuff was and how to turn on the shower. My sense of alarm grew stronger by the minute.

It was a sunny weekend so I set up a chair for him in the back garden and he just sat there twitching and rubbing at his rash and fretting about his creams, and a knot tightened in my stomach. This wasn’t my Allen. It was as if a stranger had taken over Allen’s body. How long would this last? When could I have my intelligent, loving husband back?

I couldn’t wait to get him to Haslar on the Monday morning so that they could start treating him. Despite all my nursing training, I felt utterly helpless. I had no idea what I could do to help him. Whatever it took, I would do it – but I didn’t have a clue where to even start.

CHAPTER THREE Allen (#ulink_2eaa662c-5dbb-5ad9-aac7-9f8189a116be)

Over the days and weeks after the accident, I realized that I had lost a huge chunk of my memory. Doctors reassured me that it was a common side effect of head injuries and was often just temporary but I sat obsessively trying to work out what I could and couldn’t remember. In particular my entire childhood was a blank, so I asked Sandra to tell me what she knew about it.

She said that when I was a kid I lived in a council house in Haslemere, Surrey, with my mum and my sister Suzanne. Mum and Dad split up when I was two years old and we lost contact with Dad, which must have been really tough for Mum. She struggled to cope financially and we didn’t have lots of toys or fancy bikes, parties or trips to the zoo, but there was always food on the table and clothes on our backs. In my teens, I got a boarding-school place paid for by the council and that helped to ease the burden.

My gran lived in London where she used to work for Sir Samuel Hood, the Sixth Viscount Hood, who came from a family long associated with the Navy. At Christmas time, Lord Hood used to let us come up to London and stay with my gran in his house in Eaton Square while he and the family were out at their estate in the country, and seemingly I was in awe of the place. There were huge oil paintings on the walls, of battleships at Trafalgar and great storms at sea, and all kinds of naval memorabilia like sextants and charts and telescopes. Sandra says I told her I used to love just standing in front of them staring and pretending I was on deck, clinging to the rails as huge waves lashed the sides. Much of his collection is now housed in the Royal Naval Museum in Greenwich, I believe. Anyway, I’m sure it was there that I formed my ambition to join the Navy. It must have been an exciting environment for a young boy.

Sir Samuel heard about my plans and offered to send me to Officers’ College, bless him, but I decided I would rather work my way up from the bottom. I suppose I thought the officers’ school would be full of toffs and I wouldn’t fit in. It’s not that I wasn’t ambitious, but I wanted to have hands-on experience at every level. I never wanted to be one of those people who know how to calculate the volume of a biscuit tin but have no idea how to open it.

So I signed up when I was just sixteen years old, did my basic training, where you learn how to march, clean your uniform and all that sort of thing, then I went to HMS Collingwood naval school at Fareham in Hampshire, where I was given technical training in electrics, radar systems and basic mechanics. I joined my first ship, HMS Hermione, at Portland in Dorset and we were thrown straight into war exercises, which is real ‘Boy’s Own’ stuff: they were launching thunder flashes at us, turning on the mains and flooding compartments, setting things on fire – all the things you would never normally be allowed to do on board – and we were forced to deal with it. We had to use our mattresses to plug holes in the side of the ship, and rescue ‘wounded’ civilians, and it was all a huge adventure. If this was meant to be work, I was all for it.

After that I set off on a year’s cruise round the world, following the kind of itinerary you’d pay tens of thousands of pounds for as a tourist. The most vivid early memories I have now are from this tour of duty; there are clear pictures in my mind of many of the places we visited. We went down past Gibraltar, through the Panama Canal, up to San Diego and Vancouver, then across to the Far East, Singapore, and right round the globe. Whenever we docked somewhere, I’d catch a train and go exploring instead of sitting in the nearest pub getting hammered, as some of my shipmates were prone to doing. I went to Disneyland and Las Vegas and all the major tourist attractions, and I met some wonderful people along the way.

I remember sitting in a pub in Gibraltar one sunny afternoon, with the monkeys playing on the Rock above us, and I can tell you exactly what I was drinking and what we talked about. I remember going through the Panama Canal with nothing but dense jungle towering on either side of the ship. I remember flying in a seaplane from Vancouver Island to the mainland and seeing the plane that had gone just before us ditching head-first into the water. And I remember Singapore back in the days when it was rough and ready round the docks, with beggars hustling you and taxi drivers jostling for your custom and all the old buildings that have been knocked down now to make way for pristine glass skyscrapers.

Mum wrote to the captain of my ship to complain that she never heard from me and he called me in for a chat. ‘Send her a postcard from every port,’ he told me. ‘She’s your mother, after all.’ I didn’t want to waste time writing great screeds so I got into the habit of sending a card that just had one word on it: ‘Hi!’ She has a huge collection from all over the world, and all of them just say ‘Hi!’, but that seemed to keep her happy. I got the odd letter from her with news from home, but I didn’t get homesick or miss her, as I know some of the other young lads did. I was having the adventure of a lifetime and I’d left Haslemere way behind me.

It was a bit of a shock when we got back from our trip to be told that we were being sent out to Northern Ireland, which in the late 1970s was a dangerous place to be. The Navy didn’t have to do battle on the streets, but the Army guys we met were all very jumpy. I was based at a transmission station near Belfast called Moscow Camp, where I had to do maintenance schedules for all the weapons systems and check that valves were working and so forth. I never saw any direct violence but I was aware that a lot of the guys I bumped into were virtually in shock about what was happening, living in an environment where bombs were just coming over the walls and there could be a terrorist round any corner. I suppose it was the same as is happening in Afghanistan today. You see guys drinking meths on the streets of London, and when you question them you hear that they were soldiers who came out of Northern Ireland so traumatized that they were never able to readjust to normal civilian life.

I was a bit of a swot, always putting myself up for exams, and before I left HMS Hermione I’d achieved my first promotion. I’d go and sit on the beach with all my reference books and huge carrier bags of notes, and I’d study and study. In Gibraltar I found an old gun emplacement – a pillbox, we call them – and I’d sit there and boff up. Promotion meant rank and more pay, so I always put myself up for any advancement I could, although you had to be a particular age before you could sit some of the exams. Lots of friends I’d joined up with couldn’t be bothered – they were happy just to do the job and weren’t looking to be an officer one day – but it was always an ambition of mine.

Gradually, I was put in charge of other men, and I think I was pretty fair as a boss. I was always willing to give everyone who came up the gangplank a chance, even if I knew he had been kicked off another ship. I’d say, ‘There’s your weapons system, there’re the maintenance schedules, I want you to paint it, clean it, oil it, grease it. If you need help, ask me. It’s your job now, but if it doesn’t work it’s down to you.’ And, by putting my trust in someone like that, I often found I’d get the best-maintained system on the ship. When a guy who’s made a mistake is given a second chance, he’s not going to mess up again.

I made my men work really hard, and the only punishment I used for misdemeanours was making them stick little round hole-strengtheners on all my files. We had huge books of drawings of the wiring of all our different systems, known as BRs (‘books of reference’). This was in the days before microfiches and computers were widely in use, of course. I didn’t want the paper to tear where holes were punched, so if the guys did something wrong I’d sit them down with a huge pile of sticky hole-strengtheners and make them do both sides of each page. I heard the lads called them ‘paper arseholes’, which made me smile.

I was really committed to the job – if there was still work to be done, you’d never find me slipping off to a pub onshore – and I reckon I dealt with it and my men pretty well. I saw the young guys who had gone straight into the officer-training course, usually from comfortable backgrounds where Mummy and Daddy took care of everything, and I knew I’d made the right decision to work my way up the ranks. They didn’t have an iota of experience, and yet they were supposed to be in charge of men who had huge family problems, divorces, sick children, money worries, and they had no idea what to do. It was better to be a big fish in a small pond than a small fish who was thrown right in at the deep end of the big pond, in my opinion.

I had a fantastic time along the way, on all the different ships I was posted to. The life could be very glamorous. I remember I spent six months in the Great Lakes between America and Canada on the biggest ship that had ever made its way in there. As we approached through the locks, the huge wicker fenders on the ship’s sides caught fire due to the friction, the fit was so tight. We were there as a kind of exhibition ship. Models like Jerry Hall came to do shows on the helicopter flight deck, wearing spindly high heels that tended to get caught in the mesh of the deck covering.

We sailed to Chicago, Milwaukee, Duluth, and everywhere we went there were flash parties with champagne and cocktails. We flew the ship’s helicopter over Niagara Falls, and I remember we stopped in Montreal on the way back up the St Lawrence River. I have a vivid memory of climbing a huge set of wooden steps there, up from a park to a place where there were stunning views right up and down the river for miles and miles. I’ve searched for it in Google Earth and I can find the park but I can’t find those steps, and that drives me crazy because then I start doubting myself and wondering if I’m just imagining them. But I’m sure I’m not.