По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

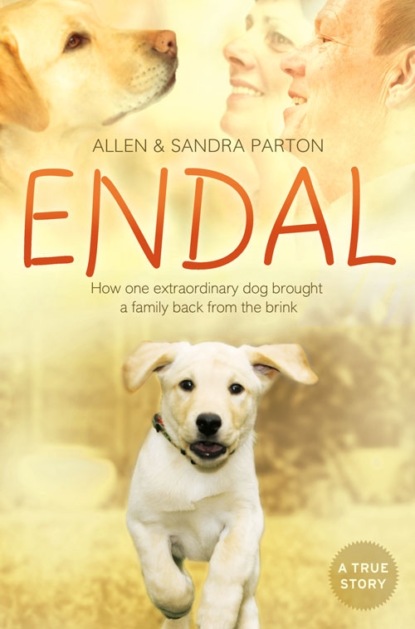

Endal: How one extraordinary dog brought a family back from the brink

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The problem is that memories are the basis for emotions, and love is based on shared history, and because I couldn’t remember any of our history I no longer felt any ‘love’ for Sandra and the kids. I’d woken up and found myself living in the middle of a life that didn’t feel like mine. It didn’t feel right. It was as though I was visiting strangers and I didn’t feel well enough to be polite or friendly to them.

I couldn’t actually remember what ‘love’ felt like. How did you know when you loved someone? I knew nothing about the woman and the two children who were trying to get through to me. They were strangers. It’s maybe a bit like watching a man in his eighties who has dementia and is being cruel to his partner because he can’t remember who she is. I had a sort of reverse dementia and I just felt emotionally blank, like an empty shell.

Sandra’s nursing experience may have meant that the staff at Haslar let her take me home, but after observing me close up for a couple of days she realized that I wasn’t fit to be there. I needed specialist help that she couldn’t give me. She took me back to Haslar on the Monday morning and had a chat with the staff and before long I was being transferred to Headley Court rehabilitation centre near Epsom in Surrey for assessment. And that’s where I stayed on and off for the next year, just coming back to visit Sandra and the children at weekends.

Originally an Elizabethan farmhouse, Headley Court was converted into a huge mansion by Lord Cunliffe, governor of the Bank of England, in the early twentieth century. During the Second World War, Canadian forces were based there, and the grounds were used for army training exercises, then after the war money was raised to convert it into a rehab centre. They have doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, a cognitive therapist, and several hydrotherapy pools and gymnasiums, as well as workshops where they make artificial limbs.

‘Right!’ I thought when they showed me around. ‘Let’s get started.’

An orderly handed me a newspaper. ‘Here you go, Allen,’ he said brightly. ‘Just have a read through and pick out a story that interests you. Any little nugget will do. When I ask you later, you have to try and remember what it was you picked out. OK?’

I grunted and opened the newspaper: the Sun. Every morning in Headley Court they brought you a paper and asked you to memorize a single item. The Sun had little square boxes of two-line stories: simple things, like amazing animal feats, or vicars who streak through their churchyards. I picked one of these and repeated and repeated it in my head, over and over again.

The other patients were sitting round the day room scanning their own papers but I tried not to look at them, focusing hard on remembering my news item. I ignored the other voices and the general chatter about the day’s news, and I tried not to look at anyone else.

Then the orderly turned to me and asked, ‘What was your story today, Allen?’

I opened my mouth – and it was gone. Just a blank space where the words had been minutes before. I shrugged, furious with myself, and turned to glare out of the window.

‘Not to worry. Maybe tomorrow,’ he said. ‘Now, who can go round the room and tell me everyone’s names? Do you want to have a go, Dave?’

Dave would love to. He always got it right. He pointed at each person and said their name, and when it came to me he said, ‘Dolly Parton,’ which was my nickname in the Navy.

And I hated Dave at that moment. I was full of rage that he could do something I couldn’t. We both had severe head injuries and were struggling with a range of disabilities, but his short-term memory for facts seemed better than mine and his speech was certainly a lot better, and I didn’t think that was fair.

Dave was an RAF instructor and had been injured in France. He’d been cycling all the way from Catterick, North Yorkshire, to Gibraltar, when he was knocked over in a hit and run. At Headley Court, Dave could always remember his news item in the morning and he could remember everyone’s names and the latest football scores, but on Sunday evenings he’d ask: ‘Has my mum been to visit me this weekend?’ even though it was only an hour or so since she’d left. He couldn’t remember that. They got him a little notebook that he kept by his bed, and he was supposed to write down everything that happened in it so he could keep track.

‘Look at your book,’ someone would say whenever he asked about his mum.

Dave was in a bad way so I should have been more charitable but I really hated him when he did better than me at those memory games. It wound me up that we had to do them every morning and I always failed.

I often thought that if you had to have a brain injury, it would be better to have a more catastrophic one so that you no longer retained any awareness of your state. The worst thing was that I knew I wasn’t stupid. I could remember that I’d had a very high-powered job designing weapons systems for the Navy. I had flashes of complete memories, but they were like tiny islands in a vast dark sea. I couldn’t put them in order or get them to join up, but I knew that I used to have a lot of people working under me, and that thousands of colleagues relied on my expertise every time they went to sea. I’d worked my way up through the ranks, serving in Northern Ireland, in the Falklands, and then in the Gulf War. I’d passed my boards to become an officer so I’d had a glittering career ahead of me with good pay and prospects. But now I couldn’t remember one paltry item in a newspaper for half an hour. It drove me nuts.

After the newspapers and the ‘naming game’, the orderlies handed out boxes of Lego along with pictures of things we were to try and build. I’d loved Lego when I was a boy. I think it had just been brought out then, and I got one of the first-ever sets. I also liked Airfix models and model railways – anything technical, basically. In Headley Court, they gave us a two-dimensional picture of the three-dimensional object we were supposed to make with the Lego, along with some instructions, and it was supposed to stimulate your cognitive powers. I could never follow the instructions, though. I had to do it my own way, figuring it out for myself, often working backwards, and usually I’d get there in the end, even if my model wasn’t 100 per cent perfect.

As I struggled with Lego blocks, memories would come back to me of sophisticated weapons systems I’d used and helped to develop. For example, in the Falklands War in 1982 we’d been testing an anti-submarine torpedo system. A huge missile was fired from a ship and when it reached the point where it detected a submarine, the torpedo was dropped with a parachute attached, and it searched the area until it found its target. We fired a practice one at an American submarine from a range of 150 miles, and it was so accurate it dropped directly into the conning tower and they couldn’t get their hatch open. It had special telemetry so that we could see what had happened during the flight, whether any equipment had been damaged during take-off and so forth – it was quite an impressive piece of machinery.

I peered at the picture of a Lego ship I’d been given, trying to work out how to make a mast, and the irony made me feel very bitter. From someone who was in charge of high-tech weaponry, I was now back in my second childhood, dependent on carers and struggling with the most basic tasks.

‘Bollocks!’ I muttered as part of the prow broke off and fell to the floor beyond my reach. I swore a lot, and that was the word that seemed to come out most often.

Most days we had some kind of workshop. If it wasn’t Lego it might be twisting a bit of wire to make a metal coat hanger. They handed out the wire, the instructions and the finished product, but I found I could never follow the written instructions. I got the lefts and rights and back and front muddled and it just hung loosely apart, no use to anyone. However, when I examined the finished product and worked backwards I could see exactly how to do it. I took my wire and copied the existing one and eventually got through the task.

Another day we had to put together a bird table. I can’t imagine they let us use saws and power drills, not with all the neurological disorders in that room. They probably gave us the pre-cut pieces and we had to assemble them in the correct order.

I saw a speech therapist most days because my words were coming out like a bark or a harsh cough, and I had the most terrible stutter that was painful to listen to. We had to go back to basics and retrain my voice box, tongue and lips with a laborious series of exercises so that I could get words out clearly – if I could remember them, that was. I still forgot lots of words, and I still resorted to snapping ‘Bollocks!’ in my frustration, but the speech therapy started to help, and that was a positive step.

The physiotherapists worked out a programme for me to try and deal with the spasms that caused me to twitch and flinch so frequently. I’d lost a lot of weight during the weeks of bed rest and my muscle tone was poor but I threw myself into a compulsive exercise routine. I found that I could swim using my upper body strength, and I could lift weights and raise myself up on the climbing wall. I began to exercise during every free moment of the day until the doctors had to come and speak to me about it.

‘Allen, you’re losing too much weight with all this exercising. You need to calm down. If you get any thinner, we’ll have to send you to hospital and get you on an intravenous drip.’

I rejected what they said, though. I thought, Fit body, fit mind, and still sneaked off to the pool or the gym whenever I could. I saw some of the other guys getting fat with enforced rest in a wheelchair or bed, and I was determined that was never going to happen to me. I’d never been overweight in my life and wasn’t about to start now.

There had been some books in the bag of possessions Sandra brought along for me and I tried to read one of them, but it was no good. By the time I got to the end of a page, I’d have forgotten the beginning and would have to go back and remind myself who the characters were and what it was all about, so I gave up before long. I practised and practised reading newspapers, determined that one morning I would pass the memory test, but to no avail. No matter how many ways I tried to fix a story in my head, it just wouldn’t stay there.

I tried writing, but it came out all wrong, with the characters back to front, for example, and that was very alarming. You need to be fastidious when you work on naval weapons systems and you couldn’t afford to put a ‘3’ the wrong way round or switch a ‘6’ for a ‘9’. But I just couldn’t see the characters in my mind’s eye any more, because you need memory for that. It got to the point where I wanted to punch the therapists – it was the speech therapists who worked with me on my handwriting – even though I knew they were only trying to help.

It seemed that I was hitting brick walls with everything I tried. When was I going to start getting better? Why couldn’t they give me some drugs, or even do an operation to get me back to normal again? This was all taking far too long.

Occasionally we’d be taken for days out. We were bussed off to Birdworld once, a huge park where they had lots of aviaries, and you could watch penguins being fed and see herons doing tricks. I wanted to walk round on my own but the orderlies insisted that we all stayed together and didn’t wander off, as if we were a bunch of schoolchildren. That was really irritating.

The other thing that annoyed me was in the coffee shop when a stupid waitress turned to one of the orderlies and asked, ‘Will he have tea or coffee?’ She was referring to me. Why not ask me directly? I thought that was terribly rude. Did she think I was mentally subnormal and incapable of answering for myself just because my walking was a bit funny and I twitched a lot?

‘C-coffee,’ I told her, annoyed with myself for stammering.

She wouldn’t meet my eye; she just scribbled it down on her pad and hurried away. She definitely wasn’t getting a tip, I decided angrily.

After that I became very self-conscious when we were out in public, noticing the way people would glance at me then look away again quickly, worried that they might be caught staring. Did I really look so bad? To me, I looked the same in the mirror as I always had, but the twitches were intensely annoying.

Sometimes we were taken to the theatre, but I had no patience with anything that didn’t contribute directly to me being cured. Sod the Shakespeare, I thought. Just make me well and get me back to work. And hurry up about it!

CHAPTER SIX Sandra (#ulink_f40ddac8-ecaa-59ec-b9f1-d363ad2f38e3)

Headley Court was a military establishment, where they all wore uniform and you needed a pass to get through the gates. The furniture in the day rooms was standard issue, exactly the same as they put in the married persons’ accommodation. The staff all seemed very nice, though, and I thought the facilities were excellent.

It was our eighth wedding anniversary, 5 November 1991, when Allen was admitted there. The first thing they did was run a series of psychometric tests to establish his brain capacity at the time. I remember one of the tests was to see whether he could put some cards into a particular sequence. The doctors told me that he would start to do it, then forget what he was doing and have to ask them to remind him. That was a bad sign, they said. It would have been better if he had laid the cards out and maybe got the sequence slightly wrong, because that would have shown that at least he understood and remembered the instruction.

They showed him a card with a shape on it and asked him what it would look like if you turned it through 90 degrees. He had no idea. They also asked him questions such as, ‘If you were in a shop paying for something that cost fifty pence and you handed over a pound, how much change would you get?’ And he didn’t have a clue. Not a clue. I was horrified when they told me. What on earth had happened to him? Liam could have answered some of the questions he was getting wrong. They got him into intensive physio to try and deal with the twitches and loss of leg control, and speech therapy to deal with his stuttering and difficulty in forming words, but what were they going to do about his loss of cognitive powers, I wondered? How could they ever fix that? Sometimes the brain can heal, but I was aware that brain injuries can also get worse over time as more brain tissue dies off.

The extent of his brain damage sank in gradually over weeks and months, rather than straight away. When he came home for weekends, I watched him like a hawk, straining to find any glimpses of the old Allen and the relationship we used to have, hoping and praying that any day now he would snap out of it and get back to normal.

‘Do you want to watch TV?’ I’d ask. ‘That programme you like is on.’

‘OK.’ He’d shrug, and we’d sit down to watch it together, but when I glanced at his face it would be blank and I could tell he wasn’t following it at all. He didn’t laugh at funny moments, or react in any way to what was happening on the screen.

When I referred to things we’d done together in the past, or places we’d been, there was a similar blankness. One day I pointed out our wedding photograph on the wall.

‘You remember our wedding day, don’t you?’ There was no recognition on Allen’s face. ‘In Wilton?’ I continued, tears coming to my eyes. ‘It was Guy Fawkes Night. Your friend Kevin was best man. Look, there he is.’ I pointed to the photo again.

Allen shook his head. ‘Don’t remember.’

‘Do you remember how we met?’ I persisted. He paused and then shook his head.

There had been plenty of clues before but it was then I finally realized that he didn’t remember me at all from before the accident. I burst out crying, covered my face and ran upstairs. I threw myself on the bed, sobbing my heart out. I suppose I must have known already, but I hadn’t wanted to admit it to myself. I wished I hadn’t pushed him. It had been easier not knowing because now I had to think about all the implications of it. If he didn’t remember me, did I really still have a husband?

That first day when I picked him up from Haslar he hadn’t had a clue who I was. The staff had told him I was his wife, so he knew that much but no more. What if they’d made a mistake? He would probably have gone off with anyone if they told him to. The wrong woman could easily have claimed him.

It made me feel grief-stricken and terribly lonely. It was like a particularly cruel type of bereavement because I no longer had a partner who loved me although someone who looked exactly the same as him was sitting downstairs. Not four months before we’d had a lovely, romantic time visiting the sights of Penang and Singapore – the temples, the markets, the huge Buddha statues, the beaches – and we’d been a proper couple who loved each other. And now I’d lost that love and I didn’t know when – or if – I would ever get it back again. Meanwhile I was burdened with someone with whom I couldn’t even have a logical conversation, who needed me to be a nurse and carer and had nothing to offer in return.