По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

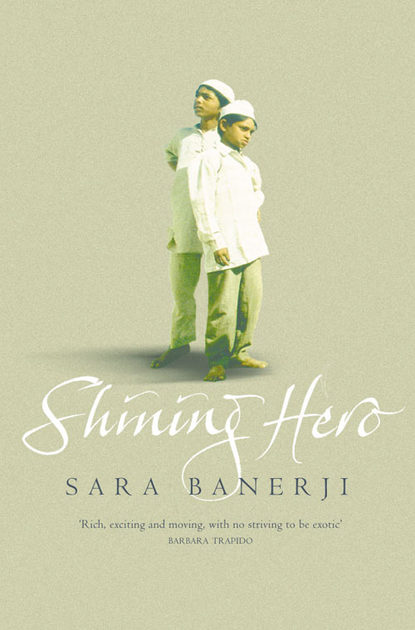

Shining Hero

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But this river, thought Koonty, is not only a woman. It is a man as well. A husband. Every year his wife, Durga, is thrown into his body, to mingle with his substance in a million muddy forms, re-emerging later in little bits, a manicured finger here, a nose ring there.

Koonty and Pandu dived for her earrings and came up with the goddess’ arm.

‘I bet you don’t dare keep that,’ said Pandu. ‘I bet you are afraid she’ll put a curse on you.’ He was always testing Koonty, trying to find out how far she would go. Her daringness excited him. Rolling the arm inside the hem of her blouse, she carried it to the rose garden and hid it there.

Several days later her mother saw the curling fingers beckoning from behind a Queen Elizabeth.

‘This will bring trouble upon you,’ she raged and beat Koonty about the ears with her supari cutters. Koonty leapt around the veranda to avoid the whacking scissors, while her mother shouted, ‘Now for certain the goddess will put a curse upon you.’ Now the fear came to Koonty. Was that what the pains had been? Durga’s late curse? Her mother had gone down to the river bank, and, ululating, had thrown the sacred arm back into the water then waited for long minutes in case celestial retribution was to follow.

Koonty could hear the sound of hymns coming from the village over the loudspeaker. They were worshipping the Durga there and this time tomorrow would be immersing the goddesses here. This time tomorrow the river will be filled with new goddesses, she was thinking, when the pain gripped Koonty again so that instantly she could not think of anything else but it. IT. Big IT pain hurling through her stomach as though she, like the deep parts of the river, had inside her body sharp stones and a tumbling current.

Her bare feet curled, her hands clenched. ‘Ouch, ouch,’ wailed Koonty and she tried to get away from the pain by squatting down into the water. She arched her back against it. Tried to duck out from under the burden of agony. But the pain was inside her, she could not escape it.

She had started feeling ill during the monsoon. She had been very sick and her mother had taken her to the doctor. But though he examined her all over he had found nothing wrong and said it must have been something she had eaten.

‘Keep her on rice and dahi for a day or two and she’ll be all right.’

But the sickness had continued.

‘Perhaps she is allergic to fish,’ the doctor said.

Koonty’s mother agreed. ‘I have noticed that it is after taking maacher jhal that she gets the worst nausea. But it is a very great pity because here in Hatipur village we get the best fish of all India. There is nothing to surpass the hilsa taken out of our own Jummuna river.’

Koonty gave up fish and sure enough after a month and a half of abstinence she suddenly became perfectly well again.

But now she was feeling worse than sick and the pain was so intense that she could not walk, but had to crouch, waiting for it to recede. She was desperate to get home but each time she tried to start on the half mile back, the pain grabbed again. She wished she had listened to her mother who was always warning her of the wrongness of wandering so far away from home.

‘What of it that the Hatibari estate is well guarded,’ her mother told her. ‘Even though there are tall brick walls all round and a stockade in the water, even though the people from the village are forbidden to come inside, yet still there are cobras in the jungly bits. And who knows, when the watchman is sleeping, dacoits might slip in from the river. You are to be married soon and a certain behaviour is expected of you. What a mess you are. It was bad enough when you were a little girl and went round with tattered clothes and untidy hair, but at the age of fifteen one expects something neater and more modest. You are a woman, Koonty, soon to be married, and it is time you began to behave like one.’

Koonty was betrothed to Pandu, the zamindar’s son. Pandu had given her a gold chain with a medal on it for her last birthday. ‘Don’t tell my father,’ he had laughed. ‘I should not even be talking to you now that we are betrothed, let alone giving you presents. But look.’

On the golden disc he had had inscribed, ‘Koonty Pandava of the Hatibari of Hatipur.’ She had giggled and felt thrilled at the words, for this was the first time she had fully taken in the full fact of what it would mean to be the lady of Hatibari.

‘To be married to the eldest son of the zamindar of Hatipur village is a tremendous honour and triumph,’ her mother would tell her at frequent intervals. ‘You must not let any breath of scandal taint your reputation or the Pandava family will call the marriage off.’ The zamindar had been very reluctant at first to allow his eldest son to marry the daughter of his estate manager.

The river flowed through land belonging to the zamindar, whose estate covered several miles in all directions and Koonty’s father lived in one of the estate houses.

That river. It ruled all their lives and even the zamindar was sometimes conquered by it. Koonty remembered the last monsoon when the golden, killing waters had lapped right up to the steps of her parents’ house and had even reached the Hatibari mansion. River had seeped into the beds of canna lilies and gaudy zinnias, softening their grip upon the soil till their roots broke free and floated away to join the garlands of the pauper dead. Koonty’s father had had to call the Hatibari servants out at midnight and get them to construct a mini dam of straw and clay to prevent the water entering the house. But in spite of all his precautions the water managed to mount the Hatibari steps and the wife of the zamindar, coming down to view the disaster, had to raise her sari above her ankles.

‘How stupid of the grandfather to have built this grand house so near the river,’ she told Koonty’s father, as he summoned yet more servants with mops and pails.

After the flood receded, the Hatibari garden was covered with river mementos; lotus leaves, boat bits, stranded fish, while the river bobbed with the memory of its recent association with land – parts of houses, drowned goats, ripped-out bits of trees. The liquid god left brown stains upon the purity of the Hatibari marble that took the servants, under Koonty’s father’s supervision, weeks of scouring, rubbing ferociously with twists of coconut rope and handfuls of sand, to eradicate.

Koonty tried to remember what she had eaten for the midday meal. Perhaps a chingdi maach had fallen into her dhall by mistake. Perhaps the cook had used fish stock when he made the mutton with kumro. It must be the fish allergy, for Durga was a mother goddess and no mother would punish so severely for the small offence of carrying away a single arm.

‘Oh, Ma, Oh, Ma,’ Koonty wailed. But the house was too far away. Her mother could not hear her though her cries were so loud that buffaloes lounging lazily, up to their shoulders in water across the river, stirred and opened their eyes and some of the mynahs, tick-picking on the buffalo backs, winged off.

She was only fifteen, she was engaged to be married and she was going to die at any moment.

Round the bend of the river and out of sight, she could hear village boys playing. From the sudden splash and laughing shriek she thought they must be hanging from the branch of an overhanging tree and dropping feet first, head first, bottom first, into the water as she and Pandu had done as recently as two years ago. The water buffaloes did not mind the boys’ shouts. They only flinched from Koonty’s screams.

Squatting low in the water, because this position seemed the least agonising, she gripped her arms around her knees and braced her body. Tilting her head back she could just see through the mango orchards and beyond the lake the great house that would have been hers if she had lived to be married. The Hatibari. Fifty windows reflecting the river. Stone lions larger than life-size on each corner of the roof. Her father was inside at this moment, preparing lists of wedding guests with the zamindar. He would never hear Koonty. The boys round the corner heard her. Laughed and shouted back. They thought she was laughing too, joining with them in their fun.

Ever since she was little she had kept coming here, though since she was soon to marry him and become a respectable wife, she no longer played on the water with Pandu. Koonty had been sitting here earlier in the year when she had first seen Suriya, the Sun God.

‘Keep away from the waterside,’ her mother kept warning. ‘That is the place from which trouble can come.’ For who can control water, who can put an impenetrable fence through a sacred river? The rest of the property was almost unassailable. The river was its only weakness in spite of the watchman who patrolled its banks. In the old days they had put up a brick wall seven feet high all along the bank but the first monsoon had washed it away so that not a brick was left standing and the bamboo water fence had to be replaced several times a year.

Koonty always sent the watchman away when she wanted to sit here. ‘If I see someone coming I will shout for you.’ She was going to be the new young mistress of the Hatibari. He did as she told him. But when she had seen a man come swimming into the Hatibari water she had not shouted for the watchman. She had kept perfectly silent the evening the Sun God came.

Koonty had first heard he was visiting their village from Boodi Ayah. Boodi had returned with the day’s food shopping, gasping and babbling with the excitement.

‘Dilip Baswani has come to the village.’

When the family looked blank she said, ‘The actor who plays the part of the Sun God in the film of the Mahabharata.’

Koonty had stared at the young woman in disbelief. ‘Dilip the glorious? There in our village? I must go and see him.’ With her parents she had seen the film five times in Calcutta.

‘He is making speeches in the tea shop. He is standing for the election,’ said Boodi Ayah. ‘I saw him with my own eyes.’

Dilip Baswani, dressed entirely in gold, had ridden into the village on a golden motorbike. His goggles were golden, he shone with gold leather and wore a plastic golden helmet.

‘He is even more beautiful than in the film, Koonty Missie. His skin looks soft as silk and his eyes are the colour of honey.’ The ayah’s excitement became so great that a cone of fresh ladies’ fingers fell from her arms and she nearly dropped the eggs.

‘Take that stuff on to the big house where they are waiting for it and stop filling my daughter’s mind with ideas,’ said Koonty’s mother sternly.

‘When can I go to hear him?’ cried Koonty. ‘I think we should go this very minute in case it is too late and he is gone.’

Koonty’s mother became stern. ‘You are only fifteen years old and about to become the wife of the young zamindar. How can you be seen among the ordinary people? A girl in your situation must stay modestly at home.’

‘What harm can it do for me only to go there and listen?’ Koonty had begged. ‘Boodi Ayah could come with me.’

‘That silly woman will be useless in such a mob,’ snapped the mother. ‘It is all her fault, with her foolish chatter, that you are so eager to see this man who is nothing but a C-grade film actor. Also a thousand people from fifty villages will be there to hear him. What will your husband-to-be’s family think if they hear you have been mingling amongst all kinds of untouchable people and gawping at a trashy film star?’

So Koonty had sat by the river instead, felt sad, cross, wished she was there among the village crowd which she could hear faintly from down the water. She imagined how impressed the girls at school would have been if she had told them she had actually seen Dilip Baswani with her own eyes like Boodi Ayah. His voice, drifting over the water, did not even sound the same as it did at the cinema.

All the girls at her school were deeply in love with one Mahabharata character or another. Koonty’s passion was Arjuna and she had a lurid poster of the actor in her bedroom.

‘Is this all you modern girls have to talk about? Cheap films and their cheaper stars. If you want to know these stories you should read the original texts,’ Koonty’s mother would reprimand.

‘Oh, Ma, what an old fuddy-duddy you are.’

In the evening she had gone back to the river just in case the Sun God started talking to the villagers again. As she sat there she had heard a commotion on the water, excited shouts, cries of awe, as though a thousand people were gathered there watching something wonderful.

‘Come and look, brother,’ she could hear one person cry to another. ‘It is the Sun God himself, here in our river.’

She heard later how the shout had spread over the countryside. People had leapt from bullock carts and run to see. Buses stopped and disgorged their passengers. The village streets emptied, shopkeepers hastily boarded up and ran to the waterside, labourers dropped their spades and rushed. Children flooded out of the school and raced their excited teacher to the river.

As the Sun God swam, he became surrounded by a hundred boys, dog-paddling alongside, and the crowds that gathered on the banks became ten deep. Trees on the waterside began cracking under the weight of people who had climbed them to catch a sight of the swimming film star and every house and hut that overlooked the water had people scrambling to the rooftops, trying to see him. Only the people of the Hatibari had remained inside, though from its upper windows could be seen the faces of the zamindar’s servants craning there, trying to get a peep but not wanting to risk the wrath of their employers by gawping openly.