По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

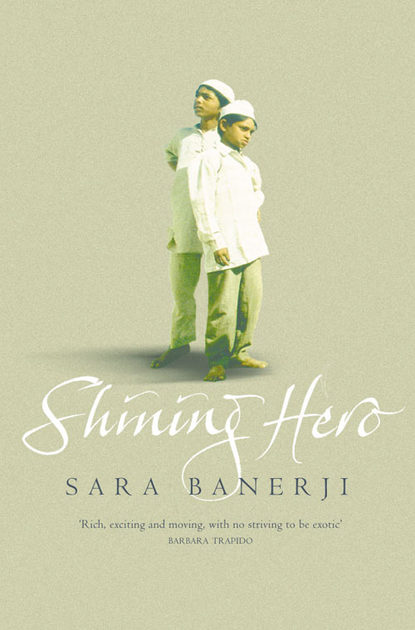

Shining Hero

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Dilip Baswani swam as fast as he could, trying, hopelessly, to shake off the mob of village boys, till ahead of him he saw the bamboo barricade cutting into the water like a fence, beyond which were trees and a domed roof. This must be the border of the Hatibari estate, he thought, the great house the villagers had told him about. Private property onto which they would not dare follow him, but onto which he, the zamindar’s future MLA, would surely be welcome. He entered the stockade and felt gratified to see the mob of boys fall back. Inside he found himself gratefully alone.

He turned a bend and looked with pleasure onto groomed grassy banks planted with flowering shrubs and free of crowds. Then he saw one lone figure sitting, feet in the water, watching him, a young girl with untidy hair and a muddy sari.

She stared with sparkling eyes, her mouth rounded in an O of amazement.

‘Hello,’ he said, but the girl just stared at him in silence.

A servant girl from the Hatibari, but pretty enough, he thought. And the age he liked.

‘What’s your name, dear?’ he asked as he scrambled out of the water. But Koonty’s lips seemed to have got stuck in their gasp of surprise.

‘I need a little rest,’ he said. ‘There are such crowds everywhere else. I don’t expect the zamindar will mind if I get my breath back here.’ He stood looking down at her, smiling. Charming, he thought.

He was not wearing a golden helmet, a gold leather jacket, gleaming goggles. He wore nothing but golden swimming shorts slung just below his small corpulence. But all the same Koonty knew exactly who he was for she had seen his face at the cinema five times.

‘I always like to take a swim in the evening,’ he said, as he sat down at Koonty’s side. ‘It is good for my digestion.’

Koonty tried to say something, opened her mouth, moved her lips, but only a sort of croaking squeak came out.

River water dripped from the Sun God’s arms and ran down his chest in rivulets.

‘Well, my dear, haven’t you got a tongue?’ He touched her arm. Gently. A shiver ran through her as though a stream of gold swished down her veins.

The crowds that were packed so thickly round the bend peered and craned, but the film star had become lost to sight. They waited for a long long time, but he did not come back. After an hour and a half they began to move away.

Now the pains were following each other so fast Koonty scarcely had time to breathe between them. She squatted lower into the water, braced herself tighter as a great racking spasm seized her. A sudden warmth gushed out of her and the water round her ankles turned red. A second spasm, huger than the first, overtook her and she could feel something heavy thrusting between her thighs as though she was being torn apart. Spreading her knees she saw, emerging into the water, something round and hazed with dark wet fur. Then another surge and the rest was there. Arms, legs, a stomach to which was attached a long twisted cord.

It lay under the water for a moment then floated up, eyes closed, lips moving.

Koonty let out a little scream of shock and darkness came over her eyes as though she was about to faint. Through the daze she reached out a hand and touched the little creature that lay half submerged in water. Its limbs began to move, tiny desperate thrashings. Its mouth began twisting, pouting. Koonty ran her hand over the child’s face and felt the movement of its lips against her fingers. As she passed her hand along its arm, a minute and wrinkled finger clutched around hers.

She was not having some terrible dream. This was true. She had had a baby. She had given birth to the Sun God’s child. She was finished now. Truly finished.

She had been worried at first. The things he asked her to do, the things he was doing to her did not seem modest. But he had reassured her. ‘You trust me, don’t you, my dear? You need not be afraid of me.’ He had spoken in his deep and husky voice and it had not come into her mind for a single moment not to trust him, any more than she would have mistrusted her father.

‘Lie like that, there, let me pull up your sari. Now open your legs a little. Good, good, that’s right.’ The doctor had talked to her like that when she had jumped out of the banyan tree, missed the river and sprained her ankle.

‘Are you sure?’ she had whispered and felt dazed with the deliciousness of his nearness, the feel of his skin, the smell of his foreign toilet water.

‘Yes, yes, my sweet. Quite sure. Now close your eyes.’ He had told her, ‘You needn’t worry about anything I do, for after all I am a god, aren’t I?’ Then he had laughed as though he had made a joke. His voice had been very rich and loving.

That evening she had taken down the poster of Arjuna and put up one of the Sun God instead.

He had told her not to worry, to trust him, but all the same she had given birth to his baby and now the young zamindar would not marry her. No one would. She would live lonely and ashamed for the rest of her life. Her parents would feel such shame that they would forbid her to go on living with them. She would not be able to live in the village either, for everyone would know. Koonty had earlier feared that she was dying. Now she was even more afraid of living.

As the water surged round her clothes and legs, carrying the blood away, she crouched numbly, gazed at the baby and felt chills of terror running through her. Her mother might have heard her earlier cries and at any moment come here to find her. She listened, her heart cracking against her ribs, for the sound of Boodi Ayah’s bare feet, Boodi sent to look for her.

‘The queen so pleased a rishi that he gave her a mantra which would evoke any god she wanted who would then, by his grace, produce in her a child.’ Koonty remembered that verse from the Mahabharata. She understood. She had pleased some rishi and her life was now destroyed because of it.

The baby began to let out little mewing cries and she hastily picked it up, the umbilical cord trailing, and tried to silence it. Its skin felt soft as silk. Softer than the Sun God’s skin. She pressed her knuckle against its mouth and at once, like the grip of a leech, its lips began sucking.

But after a moment it let go of the knuckle and began mewling again. She held it closer to her body and the baby started writhing. Her breasts had become tight and were spilling milk. She could feel it running warm down her ribs, over the place where her heart kept so loudly pounding.

To silence the baby, to stop the sound that would at any moment betray her, she pulled back her choli and held the child close. In a moment the baby had clamped upon the nipple and the only sound was a high-pitched grunt at every suck.

‘Hello, Baby God,’ she whispered, then pressing her face against the top of the head felt the soft fluff of newborn hair against her lips.

After a while the baby fell asleep. Koonty could not move. Her body was raw. Her legs felt weak. She sat there, the baby in her arms, and did not know what to do next, while the rose-ringed parakeets swooped among the trees, screaming. One extra loud bird cry startled the baby. It opened its eyes and Koonty saw that they were the colour of honey.

After that, sometimes the baby slept and sometimes fed but Koonty did not know what to do.

Night fell suddenly, the sun extinguished in a few fiery minutes. The bats came out. Fireflies began to dance among the silhouettes of trees. Behind her the lights came on in the Hatibari. She began to hear people calling her from the house. Never before had she stayed here after dark. Footsteps running over the paths. People calling, calling.

She held the baby tightly to her body, kept quite still and waited. She did not know what to do.

Her mother and Boodi Ayah were coming closer, shouting, ‘Koonty, Koonty, Koonty.’ Her mother was saying, ‘Sometimes she goes down there by the river, but she surely wouldn’t be there now, in the dark, when you have no idea who might be on the water.’

The household had been so absorbed in the news they had heard on the radio that they had not realised that Koonty was still outside. There was a fear of all-out war with Pakistan who had, that day, made an illegal military attempt to grab the Indian state of Kashmir. But now the worry about Koonty had made them forget about war and rush panicking around the estate, searching for the missing daughter.

Their voices came closer and Koonty gripped the child and felt dazed with fear. Then they began to move off again, their voices growing distant. ‘Perhaps she’s in the rose garden. Go and look there, Boodi.’

A little later, hurricane lamps and men’s voices. Her mother talking too loudly because she was afraid. ‘The only place left is the river. I am terrified that she has fallen in. Even though she can swim, this river is deceptive. The current can be very strong even for a healthy girl.’

The voice of the young zamindar. ‘Give me the lamp. I will go and look there.’ Her husband-to-be coming to where she sat with the Sun God’s baby in her lap. She could see, reflected in the river water, the swinging light approaching.

‘Koonty, Koonty,’ called the young man who was to marry her. He was getting very close. She could tell them that she had found the baby at the river’s edge. She could tell them it was a villager’s baby and she was only holding it for a moment. He was quite near now. At any moment he would see her sitting here. She could hear his panting breath. She could see his face gleaming in the lamplight. The young zamindar found her there, standing knee-deep in the river.

‘Why are you crying, Koonty? What’s the matter?’ Pandu kept asking her as he helped her back to the house. ‘You are shivering all over and wet from head to toe. Whatever have you been doing all this time? We have all been worried sick about you.’ He tried to hug her but she shook his arms off. ‘Come on, Miss Koonty,’ he whispered. ‘Tell your Pandu what’s the matter.’

After a while, when she only wept and would not speak he became angry. ‘You are hiding something. It’s those village boys, isn’t it? I heard them shouting. Have you been talking to them? I should have listened to your mother. She always said it was not proper for you to be roaming round the estate without a chaperone. She always said you’d turn out like your sister.’ All the way back to the Hatibari and even after they got inside, he kept on, sometimes trying to console her incomprehensible grief, sometimes raging against the suspected deception or infidelity. ‘You are going to be my wife. You should have some consideration. Don’t cry, my sweet. Here, wipe your face on the corner of my shawl.’

Later he told her mother, ‘She was trying to rescue a kitten, I think, though I can’t get her to talk about it.’ He felt he was doing well, impressing the mother with what an understanding husband he was going to be. ‘I heard something. A sound of mewing in the water.’

‘She was always very kind to animals,’ said Koonty’s mother and secretly thought that perhaps the zamindar’s family would be satisfied with a smaller dowry, now that they had discovered what a compassionate bride they were getting. ‘She would sacrifice herself for some small creature.’

Later the young zamindar presented Koonty with a kitten, but at the sight of the furry mewling thing she began to cry and thrust it from her. ‘Take it away. I don’t even want to look at it.’

2 A LITTLE SUIT OF SHINING ARMOUR (#ulink_eb78c085-5064-53fd-82fe-9c898546f941)

Bowed with drops of toil and languor, low, a chariot driver came,Loosely held his scanty garment and a staff upheld his frame. Karna now a crowned monarch to the humble Suta fled,As a son unto a father reverentially bowed his head.

The Emperor Aurangzeb suffered from a carbuncle until an East India Company official called Job Charnock found a physician who managed to cure it. As a reward, Job was granted a tract of land eighty miles up the Hoogly river by the Nawab of Bengal and there he founded the city of Calcutta.

By the end of the eighteenth century Calcutta was the capital of the East India Company’s government, with an opulent and lively social life and opportunities for making a quick fortune for a lucky few. To this day, throughout the town, grand Western-style buildings, now crumbling, point back to its imperial past.

Dolly, her impoverished parents’ eleventh child, was born in the house where once William Hickey had dined with his face covered with blood, because he had become ‘sadly intoxicated’ at a previous get-together and had fallen while dismounting from his phaeton.

At the time of Dolly’s birth, more than a hundred families were living in considerable squalor and poverty in Hickey’s one-time grand residence. But because the new baby was born in the year of India’s independence her parents said, ‘Perhaps the goddess is going to bless us at last even though this is only a female child.’ For this reason, when she was old enough, they sent Dolly to the local school although their other daughters had never been give such an opportunity.