По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

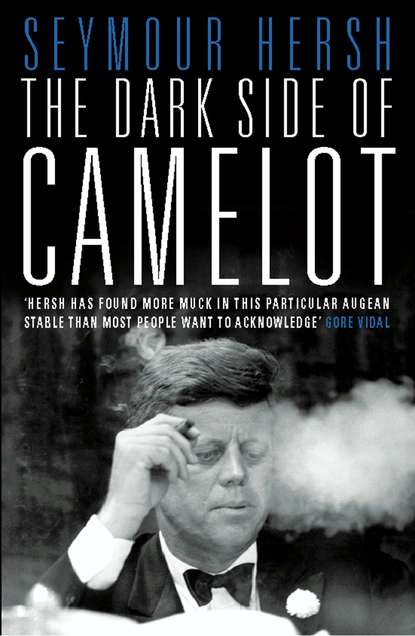

The Dark Side of Camelot

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#ulink_8ead418a-5984-5183-9e14-5806810d9f87)

In those first hours of horror, the president’s remarkable younger brother lived up to his reputation for pragmatism and toughness, notifying members of the family, worrying about the return of his brother’s body, answering legal queries from the new president, and, it seemed, losing himself in appropriate action. There would be time for mourning later. Now there was a state funeral to arrange and the president’s widow and children to console. Among his many telephone calls early that afternoon was one to McGeorge Bundy, the dead president’s national security adviser, who was told to protect Jack Kennedy’s papers. Bundy, after checking with the State Department, ordered that the combinations to the president’s locked files be changed at once—before Lyndon Johnson’s men could begin rummaging through them.

Bobby Kennedy understood that public revelation of the materials in his brother’s White House files would forever destroy Jack Kennedy’s reputation as president, and his own as attorney general. He had spent nearly three years in a confounding situation—as guardian of the nation’s laws, as his brother’s secret operative in foreign crises, and as personal watchdog for an older brother who reveled in personal excess and recklessness.

The two brothers had lied in their denials to newspapermen and the public about Jack Kennedy’s long-rumored first marriage to a Palm Beach socialite named Durie Malcolm. In 1947 Kennedy, then a first-term congressman, and Malcolm were married by a justice of the peace in an early-morning ceremony at Palm Beach. In an interview for this book, Charles Spalding, one of Kennedy’s oldest friends, broke five decades of silence by family and friends and confirmed his personal knowledge of the marriage. “I remember saying to Jack at the time of the marriage,” Spalding told me, “‘You must be nuts. You’re running for president and you’re running around getting married.’” The marriage flew apart. Spalding added that he and a local attorney visited the Palm Beach courthouse a few days later and removed all of the wedding documents. “It was Jack,” Spalding recalled, “who asked me if I’d go get the papers.” No evidence of a divorce could be found during research for this book.

The president’s files would reveal that Jack and Bobby Kennedy were more than merely informed about the CIA’s assassination plotting against Prime Minister Fidel Castro of Cuba: they were its strongest advocates. The necessity of Castro’s death became a presidential obsession after the disastrous failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961, and remained an obsession to the end. White House files also dealt with three foreign leaders who were murdered during Kennedy’s thousand days in the presidency—Patrice Lumumba, of the Congo; Rafael Trujillo, of the Dominican Republic; and Ngo Dinh Diem, of South Vietnam. Jack Kennedy knew of and endorsed the CIA’s assassination plotting against Lumumba and Trujillo before his inauguration on January 20, 1961. He was much more active in the fall of 1963, when a brutal coup d’état in Saigon resulted in Diem’s murder. Two months before the coup, Kennedy summoned air force general Edward G. Lansdale, a former CIA operative who had been involved in the administration’s assassination plotting against Fidel Castro, and asked whether he would return to Saigon and help if the president decided he had to “get rid” of Diem. “Mr. President,” Lansdale responded, “I couldn’t do that.” The plot went forward. None of this would be revealed until this book, and none of it was shared with Lyndon Johnson, then the vice president.

The vice president also did not know that Jack Kennedy’s acclaimed triumph in the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 was far from a victory. The world would emerge from fearful days of pending nuclear holocaust and be told that the president had stood firm before a Soviet threat and forced Premier Nikita Khrushchev to back down. Little of this was true, as Bobby Kennedy knew. Knowing that their political futures were at stake, the brothers had been forced to negotiate a secret last-minute compromise with the Soviets. The real settlement—and the true import of the missile crisis—remained a state secret for more than twenty-five years.

There were more secrets for Bobby Kennedy to hide.

In the last months of the Eisenhower administration, a notorious Chicago gangster named Sam Giancana had been brought into the Castro assassination effort, with Senator Jack Kennedy’s knowledge. But Giancana was far more than just another mobster doing a favor for the government—and looking for a favor in return. Giancana and his fellow hoodlums in Chicago, one of the most powerful organized crime operations in the nation, had already been enlisted on behalf of Kennedy in the 1960 presidential campaign against Republican Richard M. Nixon, providing money and union support; mob support would help Kennedy win in Illinois and in at least four other states where the Kennedy plurality was narrow. Giancana’s intervention had been arranged with the aid of both Frank Sinatra, who was close to the mob and the Kennedy family, and a prominent Chicago judge, who served as an intermediary for a meeting, not revealed until this book, between the gangster and Jack Kennedy’s millionaire father, the relentlessly ambitious Joseph P. Kennedy. The meeting took place in the winter before the election in the judge’s chambers. A few months after the election, allegations of vote fraud in Illinois were reported to Bobby Kennedy’s Justice Department—and met with no response. The 1960 presidential election was stolen.

As Bobby Kennedy knew, President Kennedy and Sam Giancana shared not only a stolen election and assassination plotting; they also shared a close friendship with a glamorous Los Angeles divorcée and freelance artist named Judith Campbell Exner. Interviews for this book have bolstered the claims of Exner, who first met Kennedy in early 1960, that she was more than just the president’s sex partner, that she carried documents from Jack and Bobby Kennedy to Giancana and his colleagues, along with at least two satchels full of cash. On one train trip from Washington to Chicago she was followed by a presidential advance man named Martin E. Underwood, who told in a 1996 interview of being ordered onto the train by Kenneth O’Donnell, Jack Kennedy’s close aide. “Kenny suggested it might be a good idea,” Underwood told me, “to go to Chicago by train. I said, ‘What train?’ It was the same train Judy took.” He watched, he said, as Exner got off in Chicago and handed a satchel to a waiting Sam Giancana. Exner, in a series of interviews for this book, further admitted that she delivered money, lots of it, from California businessmen directly to the president. The businessmen were bidding on federal contracts.

There was further evidence of financial corruption in Kennedy’s personal files. As the president’s 1964 reelection campaign neared, Kennedy was put on notice by newspaperman Charles Bartlett, his good friend, that campaign contributions were sticking to the hands of some of his political operatives. “No books are kept,” Bartlett wrote the president in July 1963, “everything is cash, and the potential for a rich harvest is clear.… I am fearful that unless you put a personal priority on learning more about what is going on, the thing may slip suddenly beyond your control.”

Robert Kennedy understood, from his own investigations, that there was independent evidence for the Bartlett allegations: one of the attorney general’s political confidants had assembled affidavits showing that money for JFK’s reelection campaign was being diverted for personal use. The Bartlett letters could not be left for Lyndon Johnson.

Yet another group of documents that had to be removed dealt with Jack Kennedy’s health. Kennedy had lied about his health throughout his political career, repeatedly denying that he suffered from Addison’s disease. But as Kennedy and his doctors knew, the Addison’s, which affects the body’s ability to fight infection, was being effectively controlled—and had been since the late 1940s—by cortisone. Far more politically damaging was the fact that the slain president had suffered from venereal disease for more than thirty years, having repeatedly been treated with high doses of antibiotics and repeatedly reinfected because of his continual sexual activity. Those records would be hidden from public view for the next thirty years. There is no evidence he told any of his many partners. Kennedy also was a heavy user of what were euphemistically known as “feel-good” shots—consisting of high dosages of amphetamines—while in the White House. Dr. Max Jacobson, the New York physician who administered the shots, was a regular visitor to the White House and accompanied the president on many foreign trips; his name was all over the official logs. Jacobson and his shots were the source of constant friction between the president’s personal aides and some members of his Secret Service detail, who persistently tried to keep the doctor, and his amphetamines, away from the White House. Jacobson’s license to practice medicine was revoked in 1975.

Jack and Bobby Kennedy were even tougher than their most ardent admirers could imagine. They seemed to glide unerringly through the nearly three years of his presidency, with its constant domestic and foreign crises. But in reality they lived and worked on the edge of an abyss. The brothers understood, as the public did not, that they were just one news story away from cataclysmic political scandal.

How to keep secrets and carry on their activities was something they had learned from their father, a successful financier and controversial public official, who masked how much money he had and how he earned it, and from their maternal grandfather, John Francis “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, a corrupt Boston politician who simply ignored the unpleasant realities of his public life. Jack and Bobby Kennedy also learned from their father and grandfather that—as Kennedys—they could enjoy freedoms denied to other men; the consequences of their acts were for others to worry about.

The family’s main antagonist was J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, who knew and was eager to take advantage—so the family was convinced—of the darkest Kennedy secrets, including the fact of Jack’s marriage to Durie Malcolm. Hoover’s biographers have told in compelling detail of Hoover’s ability to collect damaging political and personal information about the men in the White House and use it as a weapon. The relentless FBI director had been keeping score on the Kennedys, father and sons, since the early 1940s and was appalled by their public and private excesses. But the Kennedys understood that Hoover, for all of his moralizing, was a firm believer in the institution of the presidency, and could be counted on in moments of crisis, even those involving angry women looking for a way to make trouble for the president.

Hoover’s reappointment as FBI director was Jack Kennedy’s first announcement as president-elect.

Jack Kennedy’s embarrassing files were not the only materials removed from the White House on November 22. While Air Force One was still in the air, a senior Secret Service agent named Robert I. Bouck began disassembling yet another of the Kennedy brothers’ deep secrets—Tandberg tape-recording systems in the Oval Office, Cabinet Room, and the president’s living quarters on the second floor of the White House. There was also a separate Dictabelt recording system for use on the telephone lines in the president’s office and his upstairs bedroom. In the summer of 1962, John Kennedy had summoned Bouck and instructed him to install the devices and be responsible for changing the tapes. Apparently Bouck told only two people of the system—his immediate superior, James J. Rowley, chief of the Secret Service, and a subordinate who helped him monitor the equipment. It was Bouck’s understanding that only two others knew of the system while JFK was alive—Bobby Kennedy and Evelyn Lincoln, the president’s longtime personal secretary.

The seemingly open and straightforward young president could activate the recording system when he chose, through a series of hidden switches that Bouck installed in the Oval Office and on the president’s desk. “His desk had a block with two or three pens in it and a place for paper clips,” Bouck said in a 1995 interview for this book. “I rigged one of those pen sockets so he could touch a gold button—it was very sensitive—and switch it [the tape recorder] on.” Another secret switch was placed in a bookend that the president could reach while lounging in his chair. “All he had to do was lean on it,” Bouck told me. A third was tucked away on a small table in front of the Oval Office desk, where Kennedy often met with aides and visitors. (Bouck would say of the tabletop switch only that it was placed “under something that was unlikely to be taken away.”) Microphones were also hidden in the walls of the Cabinet Room and on the desk and coffee table in the president’s office. Kennedy made little use of the devices in the family living quarters, Bouck said. The president could record telephone conversations by flicking a switch on his desk that activated a light in Evelyn Lincoln’s office, alerting her to turn on the Dictabelt system. During its sixteen months of operation, Bouck said, the taping system produced “at least two hundred” reels of tapes. “They never told me why they wanted the tapes,” Bouck said, “and I never had possession of any of the used tapes.”

Bouck had no ambivalence as he tore his way through the office that now belonged to President Lyndon Johnson. Getting rid of the tapes and the taping system was something he did for Jack Kennedy: “I didn’t want Lyndon Johnson to get to listen to them.” The taping system was gone within hours, along with the reels of Oval Office and Cabinet Room recordings.

(#ulink_29c37288-16a6-5627-a6ac-2c9094f88ff9)

By late afternoon it was getting crowded at Hickory Hill, as family friends, neighbors, and Justice Department aides—as if drawn by some survival instinct—made their way to the attorney general’s side. Surrounded by sympathetic mourners, Robert Kennedy still found time to operate in secret, and he now turned away briefly from his need to protect his brother to seek out who might have gunned him down. His first suspect was Sam Giancana, the Kennedy family’s secret helper in the 1960 election and in Cuba. He had been repeatedly heard on FBI wiretaps and bugs complaining about being the victim of a double cross since 1961: Bobby Kennedy had made the Chicago outfit a chief target of the Justice Department, and the mob’s take was down.

Another target of Bobby’s crime war was Jimmy Hoffa and his corrupt Teamsters Union; one of his most experienced operatives in that war was Julius Draznin, who was by 1963 a supervisor in Chicago for the National Labor Relations Board and responsible for liaison with the Justice Department. Bobby Kennedy had personally arranged for the installation of a secure telephone in Draznin’s apartment on Chicago’s South Side—one of many such telephones in what became an extraordinary and little-known communications system linking the attorney general with a select group of loyal government investigators across the nation. Draznin had spoken to Kennedy a few times on the secure telephone, but he talked most often with senior Kennedy aides such as Walter Sheridan, a Justice Department official closely involved with the Hoffa investigations. Draznin understood that such contacts were not to be reported to his labor board superiors. Nor, of course, were they to be mentioned to anyone from Hoover’s FBI.

Draznin’s secure telephone rang twice on November 22. The first call came from Sheridan “four or five hours” after the assassination, Draznin told me in a series of interviews for this book. “Bobby is going to call you,” Sheridan said. “He has some questions he wants you to help on—about the assassination.” Kennedy’s call came moments later. “We need all the help you can give. Can you open some doors for us in Chicago?” Kennedy made it clear, Draznin told me, that he suspected that Sam Giancana’s mob might have been behind his brother’s murder.

Moments after the call to Draznin, Kennedy dashed to the Pentagon, and with Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara and others flew by helicopter to Andrews Air Force Base, the home base for Air Force One, in suburban Maryland. A crowd of three thousand saddened Americans watched quietly as the presidential plane landed a few minutes after six o’clock. There was a sorrowful embrace between the president’s brother and his widow. A small entourage, Bobby among them, then followed the body to Bethesda Naval Hospital, where an autopsy was to be performed.

Despite his grief, Kennedy continued to focus on the need to protect the Kennedy reputation. At the hospital, he took Evelyn Lincoln aside. “Bobby said to me that Lyndon’s people were digging around in the president’s desk,” Lincoln told me in the most candid interview she ever gave, shortly before her death in 1995. She and her husband were at her desk packing her files of presidential papers by eight o’clock the next morning, she said, and were called into the Oval Office by President Johnson at eight-thirty. “He said, ‘I need you more than you need me’”—a remark Johnson made to all of the Kennedy staff aides—“and then said, ‘I’d like for you to move out of the office by nine A.M.’” Mrs. Lincoln immediately reported to Bobby Kennedy, who was waiting in a room nearby. “He couldn’t believe it,” Mrs. Lincoln said. “He got Johnson to agree to twelve noon.” Johnson eventually decided to delay a few days before moving into JFK’s office, but Bobby Kennedy was taking no chances; he had already ordered that his brother’s Oval Office and National Security Council files be packed overnight and shipped to a sealed office by the crack of dawn on Saturday, November 23.

The president’s personal papers and the White House tape recordings ended up in the top-secret offices of one of Jack Kennedy’s most cherished units in the government—the Special Group for Counterinsurgency, whose mission was to battle communist-led wars of liberation in Latin America and Southeast Asia. The Special Group’s third-floor corridor in the nearby Executive Office Building was the most secure area of the White House complex, with armed guards on patrol twenty-four hours a day. The president’s papers and tape recordings were now safe.

One final act of cover-up occurred in the early-morning hours of Saturday, November 23, as Bobby Kennedy and an exhausted Jacqueline Kennedy returned to the White House, accompanying the body of the fallen president. There was a brief meeting between Kennedy and J. B. West, the chief White House usher, who turned over the Usher’s Logs—the most detailed records that existed of the visitors, public and private, to the president’s second-floor personal quarters. The logs provided what amounted to a daily scorecard of the president’s sex partners, who were usually escorted by David Powers, JFK’s longtime personal aide. The logs, traditionally considered to be the public records of the presidency, were never seen again by West, and are not among the documents on file at the Kennedy Library.

Bobby Kennedy knew, as did many of the men and women in the White House, that Jack Kennedy had been living a public lie as the attentive husband of Jacqueline, the glamorous and high-profile first lady. In private Kennedy was consumed with almost daily sexual liaisons and libertine partying, to a degree that shocked many members of his personal Secret Service detail. The sheer number of Kennedy’s sexual partners, and the recklessness of his use of them, escalated throughout his presidency. The women—sometimes paid prostitutes located by Powers and other members of the so-called Irish Mafia, who embraced and protected the president—would be brought to Kennedy’s office or his private quarters without any prior Secret Service knowledge or clearance. “Seventy to eighty percent of the agents thought it was nuts,” recalled Tony Sherman, a former member of Kennedy’s White House Secret Service detail, in a 1995 interview for this book. “Some of us were brought up the right way,” Sherman added. “Our mothers and fathers didn’t do it. We lived in another world. Suddenly, I’m Joe Agent here. I’m looking at the president of the United States and telling myself, ‘This is the White House and we protect the White House.’”

Another Secret Service agent had the unceremonious chore of bringing sexually explicit photographs of a naked president with various paramours to the Mickelson Gallery, one of Washington’s most distinguished art galleries, for framing. In a reluctantly granted interview in mid-1996, Sidney Mickelson, whose gallery framed pictures for the White House in the 1960s (and continued to do so for the next three decades), acknowledged that “over a number of years we framed a number of photographs of people—naked and often lying on beds—in the Lincoln Room. The women were always beautiful.” In some cases the photographs included the president with, as Mickelson carefully described it, “a group of people with masks on.” Another memorable photograph, Mickelson added, involved the president and two women, all wearing masks. “The Secret Service agent said it was Kennedy,” Mickelson told me, “and I had no reason to doubt it.” The photographs were always of high quality, Mickelson added, similar to those taken by official White House photographers.

Mickelson told me that the procedure for handling the extraordinary material was always the same. A Secret Service agent would arrive at his shop—ten blocks from the White House—early in the morning with a photograph. “I’d look at it, take the measurement, and then he’d take it back.” The agent would return that evening, after the gallery closed, and wait once again in the same room with Mickelson until he completed the framing. He never had a chance, Mickelson told me, to make a copy of a photograph—something he thought about doing—because “the Secret Service agent was always with it.”

Mickelson, who was seventy years old when we spoke, told me that he had remained especially troubled by the photographs, and his role in framing them, because at the time his shop was deeply involved in the restoration of the White House, managed by the first lady. “I had a very good relationship with Jackie and I respected her,” Mickelson said. “But,” he added with a shrug, “my feeling is whatever the White House sends me …

“No other White House did this.”

John F. Kennedy’s recklessness may finally have caught up with him in the last weeks of his life. One of his casual paramours in Washington, the wife of a military attaché at the West German Embassy, was believed by a group of Republican senators to be a possible agent of East German intelligence. In the ensuing panic, the woman and her husband were quickly flown out of Washington, and Robert Kennedy used all of his powers as attorney general, with the help of J. Edgar Hoover, to quash investigations by the Congress and the FBI. The potential damage of the presidential liaison was heightened, as the worried Kennedy brothers understood, by the ongoing sex scandal involving John Profumo, the British secretary of state for war, that was riveting London—and the British tabloids—throughout the summer of 1963. The government of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan barely survived the scandal.

Kennedy may have paid the ultimate price, nonetheless, for his sexual excesses and compulsiveness. He severely tore a groin muscle while frolicking poolside with one of his sexual partners during a West Coast trip in the last week of September 1963. The pain was so intense that the White House medical staff prescribed a stiff canvas shoulder-to-groin brace that locked his body in a rigid upright position. It was far more constraining than his usual back brace, which he also continued to wear. The two braces were meant to keep him as comfortable as possible during the strenuous days of campaigning, including that day in Dallas.

Those braces also made it impossible for the president to bend in reflex when he was struck in the neck by the bullet fired by Lee Harvey Oswald. Oswald’s first successful shot was not necessarily fatal, but the president remained erect—and an excellent target for the second, fatal blow to the head. Kennedy’s groin brace, which is now in the possession of the National Archives in Washington, was not mentioned in the public autopsy report, nor was the injury that had led to his need for it.

November 22, 1963, would remain a day of family secrets, carefully kept, for decades to come.

(#ulink_09837209-d52f-5af3-9c77-826371b30cd4) Morgenthau would not learn until he was interviewed for this book that Robert Kennedy had planned to tell him that afternoon that he was resigning his cabinet post and wanted Morgenthau to replace him as attorney general. Joseph F. Dolan, who was one of Kennedy’s confidants in the Justice Department, said in a 1995 interview for this book that Kennedy “was going to run” his brother’s 1964 reelection campaign.

(#ulink_1623ac8d-cfda-5fab-824b-efab6a5fae5c) The tape recordings remained in direct control of the Kennedy family until May 1976, when they were deeded to the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston. In a report issued in 1985, the library acknowledged that it was “impossible to establish with any certainty how much might have been removed” from the collection prior to 1975. “That at least some items were removed cannot be doubted.” Some Dictabelt tapes of telephone conversations were also discovered to be in the possession of Evelyn Lincoln after her death in 1995.

2 JACK (#ulink_6b10adb6-4ebe-5e05-b3bc-c2ee05c20ae7)

Jack Kennedy was a dazzling figure as an adult, with stunning good looks, an inquisitive mind, and a biting sense of humor that was often self-mocking. He throve on adoration and surrounded himself with starstruck friends and colleagues. Women swooned. Men stood in awe of his easy success with women, and were grateful for his attentions to them. Today, more than thirty years after his death, Kennedy’s close friends remain enraptured. When JFK appeared at a party, Charles Spalding told me, “the temperature went up a hundred and fifty degrees.”

His close friends knew that their joyful friend was invariably in acute pain, with chronic back problems. That, too, became a source of admiration. “He never talked about it,” Jewel Reed, the former wife of James Reed, who served in the navy with Kennedy during World War II, said in an interview for this book. “He never complained, and that was one of the nice things about Jack.”

Kennedy kept his pain to himself all of his life.

The most important fact of Kennedy’s early years was his health. He suffered from a severe case of Addison’s disease, an often-fatal disorder of the adrenal glands that eventually leaves the immune system unable to fight off ordinary infection. No successful cortisone treatment for the disease was available until the end of World War II. A gravely ill Kennedy, wracked by Addison’s (it was undiagnosed until 1947), often seemed on the edge of death; he was stricken with fevers as high as 106 degrees and was given last rites four times. As a young adult he also suffered from acute back pain, the result of a college football injury that was aggravated by his World War II combat duty aboard PT-109 in the South Pacific. Unsuccessful back surgery in 1944 and 1954 was complicated by the Addison’s, which severely diminished his ability to heal and increased the overall risk of the procedures.

Kennedy and his family covered up the gravity of his illnesses throughout his life—and throughout his political career. Bobby Kennedy, two weeks after his brother’s assassination, ordered that all White House files dealing with his brother’s health “should be regarded as a privileged communication,” never to be made public. Over the years, nonetheless, biographies and memoirs have revealed the extent of young Jack Kennedy’s suffering. What has been less clear is the extent of the impact his early childhood illnesses had on his character, and how they shaped his attitudes as an adult and as the nation’s thirty-fifth president.

Kennedy’s fight for life began at birth. He had difficulty feeding as an infant and was often sick. At age two he was hospitalized with scarlet fever and, having survived that, was sent away to recuperate for three months at a sanatorium in Maine. It was there that Jack, torn from his parents and left in the care of strangers, demonstrated the first signs of what would be a lifelong ability to attract attention by charming others. He so captivated his nurse that it was reported that she begged to be allowed to stay with him. Poor health plagued Jack throughout his school years. At age four, he was able to attend nursery school for only ten weeks out of a thirty-week term. At a religious school in Connecticut when he was thirteen, he began losing weight and was diagnosed with appendicitis. The emergency operation—a family surgeon was flown in for the procedure—almost killed him; he never returned to the school. Serious illness continued to afflict Kennedy at prep school at Choate, and local physicians were unable to treat his chronic stomach distress and his “flu-like symptoms.” He was diagnosed as suffering from, among other ailments, leukemia and hepatitis—afflictions that would magically clear up just as his doctors, and his family, were despairing. Once again, he made up for his sickliness with charm, good humor, and a winning zest for life that kept him beloved by his peers, as it would throughout his life.

His loyal friend K. LeMoyne Billings, who was a classmate at Choate, waited years before revealing how much Kennedy had suffered. “Jack never wanted us to talk about this,” Billings said in an oral history for the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, “but now that Bobby has gone and Jack is gone, I think it really should be told … Jack Kennedy all during his life had few days when he wasn’t in pain or sick in some way.” Billings added that he seldom heard Kennedy complain. Another old friend, Henry James, who met Jack at Stanford University in 1940, eventually came to understand, he told a biographer, that Kennedy was not merely reluctant to complain about pain and his health but was psychologically unable to do so. “He was heartily ashamed” of his illnesses, James said. “They were a mark of effeminacy, of weakness, which he wouldn’t acknowledge. I think all that macho stuff was compensation—all that chasing after women—compensation for something that he hadn’t got.” Kennedy was fanatic about maintaining a deep suntan—he would remain heavily tanned all of his adult life—and he once explained, James said, that “it gives me confidence.… It makes me feel strong, healthy, attractive.” A deep bronzing of the skin when exposed to sunlight was, in fact, one of the symptoms of Addison’s disease.

Kennedy had few options other than being strong and attractive; his father saw to that. Joseph Kennedy viewed his son’s illness as a rite of passage. “I see him on TV, in rain and cold, bareheaded,” Kennedy told the writer William Manchester in 1961, “and I don’t worry. I know nothing can happen to him. I tell you, something’s watching out for him. I’ve stood by his deathbed four times. Each time I said good-bye to him, and he always came back.… You can’t put your finger on it, but there’s that difference. When you’ve been through something like that back, and the Pacific, what can hurt you? Who’s going to scare you?”

Jack was always striving to be strong for his father; to finish first, to shape his life in ways that would please Joe. Jack’s elder brother, Joseph Jr., always in flourishing health, had been his father’s favorite, the son destined for a successful political career in Washington. With Joe Jr.’s death in 1944 as a naval aviator, Jack became the focus of Joe Kennedy’s aspirations. In Jack’s eyes, his father could do little wrong. Many of Jack’s friends thought otherwise, but learned to say nothing. “Jack was sick all the time,” Charles Spalding told me in 1997, “and the old man could be an asshole around his kids.” During a visit to the Kennedy home in Palm Beach, Florida, in the late 1940s, Spalding said, he and his wife, Betty, were preparing to go to a movie with Jack and his date, Charlotte MacDonald. Spalding went upstairs with Jack and Charlotte to say good night to Joe, who was shaving. The father turned to Charlotte and said scathingly, “Why don’t you get a live one?” Spalding was appalled by the gratuitous comment about his best friend’s chronic poor health and couldn’t resist making a disparaging remark about Joe Kennedy to Jack. The son’s defense of his father was instinctive: “Everybody wants to knock his jock off, but he made the whole thing possible.”

Charles Bartlett, another old friend, saw both Joe Kennedy’s toughness and his importance to his son. Bartlett, who became friends with Jack in Palm Beach after the war, declared that Joe Kennedy “was in it all the way. I don’t think there was ever a moment that he didn’t spend worrying how to push Jack’s cause,” especially as his son sought the presidency in 1960.

“He pushed them all,” Bartlett, who later became the Washington bureau chief of the Chattanooga Times, told me in an interview for this book. “He pushed Bobby into the Justice Department, and he made Jack do things that Jack would probably rather not have done. He was very strong; he’d done things for the kids and wanted them to do some things for him. He didn’t bend. Joe was tough.” And yet, Bartlett added, “I just found that, in so many things, his judgment down the road was really enormous. You had to admire him.”