По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

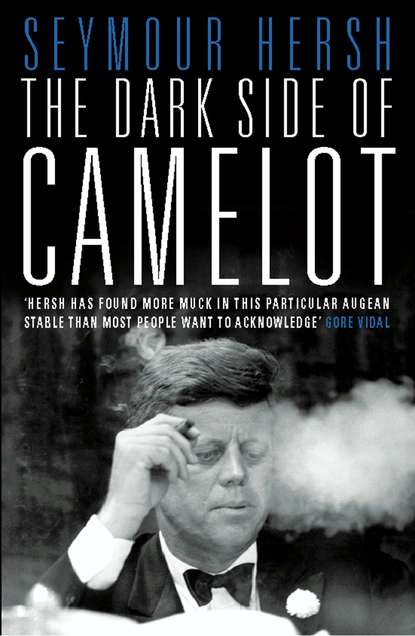

The Dark Side of Camelot

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

James Roosevelt’s business disappointments no doubt figured in his father’s decision, despite opposition from his advisers, to name him his personal secretary at the beginning of his second term. Kennedy, not surprisingly, continued to lavish attention, affection, and, undoubtedly, women on the president’s son. “You know as far as I am concerned,” Kennedy wrote Roosevelt and his wife in a January 1937 letter on file in the FDR Library, “you are young people and struggling to get along and I am your foster-father.”

Foster father was hyperbole, but James Roosevelt, as personal secretary to his father, played a major—and not fully known—role in assuring Kennedy’s nomination as ambassador to England. The most extensive account of the machinations appeared in Memoirs, Arthur Krock’s autobiography, published in 1968. Krock, then the columnist and Washington bureau chief of the New York Times, had a secret life. By the late 1930s he had become another of Kennedy’s wholly owned subsidiaries—a journalist who vacationed at Kennedy’s Florida home, shared in his lifestyle, and very often wrote whatever Kennedy wanted. It was a pattern that would be repeated again and again by the reporters covering Joe and, later, Jack Kennedy. In his autobiography, Krock told of a dinner with Kennedy, then chairman of the Maritime Commission, at which James Roosevelt arrived and took Kennedy into another room for an extended private conversation. Kennedy’s nomination as ambassador was rumored at the time, and, Krock noted, there was sharp opposition inside the White House and from liberals in the Congress. After the meeting, a very angry Kennedy told Krock that young Roosevelt had proposed that he take an appointment as secretary of commerce. “Well, I’m not going to,” Kennedy said. “FDR promised me London, and I told Jimmy to tell his father that’s the job, and the only one, I’ll accept.”

Kennedy got his nomination in December 1937 and arrived in prewar London full of ambition.

Kennedy’s rise and fall as ambassador in London has been often told: a brief honeymoon with the British press and public, much of it revolving around his highly social and photogenic children, and then a relentless fall from grace. Kennedy was reviled for his defeatism. His widely quoted belief was that Great Britain had neither the will nor the armaments to win a war against Nazi Germany. And he was ridiculed for his perceived cowardice during the intensified Luftwaffe bombing of London in 1940, when he chose to spend his nights at a country estate well away from the targeted city centers. German Foreign Ministry documents published after World War II show that Kennedy, without State Department approval, repeatedly sought a personal meeting with Hitler on the eve of the Nazi blitzkrieg, “to bring about a better understanding between the United States and Germany.” His goal was to find a means to keep America out of a war that he was convinced would destroy capitalism.

There is no evidence that Ambassador Kennedy understood in the days before the war that stopping Hitler was a moral imperative. “Individual Jews are all right, Harvey,” Kennedy told Harvey Klemmer, one of his few trusted aides in the American Embassy, “but as a race they stink. They spoil everything they touch. Look what they did to the movies.” Klemmer, in an interview many years later made available for this book, recalled that Kennedy and his “entourage” generally referred to Jews as “kikes or sheenies.”

Kennedy and his family would later emphatically deny allegations of anti-Semitism stemming from his years as ambassador, but the German diplomatic documents show that Kennedy consistently minimized the Jewish issue in his four-month attempt in the summer and fall of 1938 to obtain an audience with Hitler. On June 13, as the Nazi regime was systematically segregating Jews from German society, Kennedy advised Herbert von Dirksen, the German ambassador in London, as Dirksen reported to Berlin, that “it was not so much the fact that we wanted to get rid of the Jews that was so harmful to us, but rather the loud clamor with which we accompanied this purpose. He himself understood our Jewish policy completely.” On October 13, 1938, a few weeks before Kristallnacht, with its Brown Shirt terror attacks on synagogues and Jewish businesses, Kennedy met again with Ambassador Dirksen, who subsequently informed his superiors that “today, too, as during former conversations, Kennedy mentioned that very strong anti-Semitic feelings existed in the United States and that a large portion of the population had an understanding of the German attitude toward the Jews.”

(#ulink_c5ff8b88-88ed-5776-a813-495c4bb3fdd7)

Kennedy knew little about the culture and history of Europe before his appointment as ambassador and made no effort to educate himself once in London. He made constant misjudgments. In the summer of 1938, for example, he blithely assured the president in a letter, described in the published diaries of Harold Ickes, FDR’s secretary of the interior, that “he does not regard the European situation as so critical.” Diplomats serving on the American Desk in the British Foreign Office quickly came to fear—and hate—Kennedy. They compiled a secret dossier on him, known as the “Kennediana” file, which would not be declassified until after the war. In those pages Sir Robert Vansittart, undersecretary of the Foreign Office, scrawled, as war was spreading throughout Europe in early 1940: “Mr. Kennedy is a very foul specimen of a double-crosser and defeatist. He thinks of nothing but his own pocket. I hope that this war will at least see the elimination of his type.”

The Foreign Office notes also included many allegations of Kennedy’s profiteering once the war began. Kennedy, still very much in control of Somerset Importers, was suspected of having commandeered valued transatlantic cargo space for the continued importation of British scotch and gin; it was further believed that he was abusing his position of trust as a high-level government insider to support his Wall Street trading. No proof of such business activity was then available to the British Foreign Office—officially, at least—but Kennedy was worried that he might be doing something illegal: in April 1941, shortly after his return to the United States, he telephoned the State Department and inquired whether there were rules governing private financial transactions of U.S. officials serving abroad. Kennedy was told that Congress had passed legislation in 1915 making any business dealings for profit illegal.

In 1992 Harvey Klemmer, an ex-newspaperman who served as Joe Kennedy’s personal public relations aide at the Maritime Commission and had the same role in London, acknowledged in a British television interview that the Foreign Office suspicions more than fifty years before were valid: Kennedy, in fact, did continue to be a major investor and speculator on Wall Street, placing buy and sell orders by telephone through John J. Burns, a former justice of the Massachusetts State Supreme Court who was retained by Kennedy to run his New York office, a practice he continued into the 1950s. Klemmer, depicted by one British diplomatic reporter as Kennedy’s “brains trust,” remained silent about Joe Kennedy until a few months before his death, from cancer, in 1992, when he did a brief on-air interview with television producer Phillip Whitehead on Thames TV. Klemmer, who was severely disfigured from his cancer, also granted Whitehead an extraordinary interview on audiotape—much of it never made public until it was obtained for this book. The unedited transcripts of the two interviews provide a rare inside look at the Kennedy embassy. “Kennedy continued to do business as usual while in London,” Klemmer told Whitehead. One night, while out at dinner, the ambassador left the table for a telephone call. “He was gone a long time. When he came back, he said, ‘Well, the market’s going to hell. I told Johnny [Burns] to sell everything.’” Also at the dinner, Klemmer recalled, was “a Jewish friend of his and mine.… In a little while [the friend] began to fidget and finally excused himself on the basis that he had something important to do and left. As soon as he had left, Kennedy said, ‘Watch the son of a bitch go out and sell. Actually the market is doing very well and I told Johnny to buy.’”

Kennedy was equally unprincipled in his use of ambassadorial perquisites. Klemmer told Whitehead that one of his principal duties at the embassy was shipping Kennedy’s liquor. “Using his name and the prestige of the embassy and also my connection with the Maritime Commission, I was able to get shipping space for up to, I think, around 200,000 cases of whiskey at a time when shipping space [from England to the United States] was very scarce.” Kennedy’s abuse of office on behalf of Somerset Importers was so extreme, Klemmer said, that “a British friend in the Ministry of Shipping came to see me one day and said, ‘You’d better lay off with the ambassador’s whiskey, because some of the other distillers, who can’t get shipping space, are going to have the question raised in Parliament. He’s using the influence of the American Embassy to preempt shipping space.’ So,” Klemmer concluded, “we kind of tapered off a little bit after that.” Kennedy ignored the widespread gossip about his whiskey dealing, Klemmer added: “He just brushed it off.… His stock reply to any criticism was ‘To hell with them.’… He didn’t take things like that seriously.”

London’s concerns about the American ambassador went far beyond defeatism and profiteering. British policy, after the failure of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler at Munich, was unstated but nonetheless clear: to somehow get the United States into the war against Germany. In May 1940, with France on the verge of defeat, Winston Churchill, who had been serving as first lord of the Admiralty, replaced the failed Chamberlain. A few days later, while shaving, Churchill announced to his son, Randolph: “I think I can see my way through.” Randolph, recalling the conversation in a 1963 memoir, asked, “Do you mean we can avoid defeat or defeat the bastards?” His father, flinging his razor into a washbasin, proclaimed, “Of course I mean we can beat them.” Asked how, the new prime minister simply said, “I shall drag the United States in.”

It was clear even before Churchill became prime minister that Joe Kennedy, with his access to Roosevelt, his desire to meet personally with Adolf Hitler, and his eagerness to avoid American involvement in the war at all costs, had become a national security risk to England. Historians are in agreement that Kennedy was a priority target of Britain’s famed MI5, its counterintelligence service, and was subjected to physical surveillance as well as extensive wiretapping. No such files have been declassified and released by the British government, despite repeated requests.

Harvey Klemmer knew firsthand, though, about MI5’s close surveillance. Kennedy was seeing a wealthy English divorcée who was in touch with Sir Oswald Mosley, a leading British fascist. The woman, Klemmer said in his interview, “told me that Joe had asked her to initiate … contact with Mosley,” in the mistaken belief that the fascists in England were more numerous than they were. “So one day [Kennedy] asked me to take her home and it was in one of her cars. So I did. And on the way back I was stopped by a man in uniform who said there was an air raid or invasion drill in progress. I would have to leave my car for a while and take refuge with them in a nearby country home.… I wondered if there was something going on, and so I arranged my gloves on the seat in a certain way, and I arranged some of the papers in the glove compartment.” After an hour, when Klemmer was given the all-clear sign, “I looked and I could see the car had been searched.… I knew I was under suspicion” by British intelligence, Klemmer said, “because of my association with him. My files at the embassy were searched,” as was, he believed, his London apartment. He and others at the embassy did learn later, Klemmer told Whitehead, that “the British had Kennedy’s telephone tapped.”

Given his precarious position in London, some of Kennedy’s actions seem stupefying.

In the spring of 1939, shortly after Germany’s occupation of Czechoslovakia, Kennedy—despite being instructed not to do so by Washington—encouraged a bizarre and little-known scheme being actively promoted by a naive American automobile executive who had been told in Berlin that the Nazi regime would agree to peace concessions and a general disarmament in return for an Anglo-American gold loan totaling between $500 million and $1 billion. The American, James D. Mooney, president of General Motors Overseas, flew to London to discuss the German proposal with an equally impressed Kennedy at the American Embassy. According to Mooney’s unpublished memoir, made available for this book, Kennedy urged Mooney to return to Berlin and inform the Germans that he would “certainly like to have a talk with them, quietly and privately.” Mooney’s papers reveal that it was agreed that Kennedy would meet secretly in Paris with Dr. Helmut Wohltat, a high-level Nazi official who was a deputy to Field Marshal Hermann Göring. Only after Kennedy made the commitment to Mooney did he send a vaguely worded cable to the State Department, wondering whether there would be “any objections” to his flying to Paris to meet with Mooney and “a personal friend of Hitler.” He was emphatically denied permission to make the trip by Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Mooney, still eager to involve Kennedy, returned to London and presented the ambassador with the list of the promised German concessions that would result from the gold loan. “What a wonderful speech could be built up from these points back home!” Kennedy exclaimed, according to Mooney’s notes. Kennedy then took his case for a meeting directly to President Roosevelt, and was told once again to have nothing to do with the proposal.

Nonetheless, Kennedy met in secret with Mooney and Wohltat at a hotel in London on May 9, 1939. “Each man made an excellent impression on the other,” Mooney recorded in his unpublished memoir. “It was heartening to sit there and witness the exertion of real effort to reach something constructive.” Within days, London’s Daily Express blew everyone’s cover by reporting on its front page, under the headline “Goering’s Mystery Man Is Here,” that Wohltat had arrived in London “on a special mission.” Neither Kennedy nor Mooney was named in the article, but a few days later Kennedy was singled out for censure in The Week, a radical weekly newsletter. Its editor, Claud Cockburn, wrote that Kennedy, in his talks with Germans, “uses language which is not merely defeatist, but anti-Rooseveltian.… Mr. Kennedy goes so far as to insinuate that the democratic policy of the United States is a Jewish production, but that Roosevelt will fall in 1940.” The article was reprinted in the New York Post and eventually brought to Roosevelt’s attention by Harold Ickes. In his diaries, Ickes noted that “the President read this and said to me: ‘It is true.’”

Kennedy’s indiscretion knew no limits. After Munich he had summoned a group of American journalists to the embassy and, among other things, briefed them off the record about a most secret plot by a group of dissident German generals to overthrow Hitler. James Reston of the New York Times summarized the briefing in Deadline, his 1991 memoir: “It was known in London on the eve of Munich that … a group of German officers led by Generals Halder and Beck had a plan to overthrow the Führer. Fearing war on three fronts, these conspirators informed officials in Westminster [the British Foreign Office]—so Ambassador Kennedy told us—that they would arrest Hitler if the British and French took military action to block the invasion of Czechoslovakia.” It would not become publicly known until after the war that the plotters, General Ludwig Beck, then chief of the German General Staff, and his deputy, Franz Halder—their lives very much at stake—had approached the British Foreign Ministry. The Beck-Halder partnership was the most serious early resistance to Hitler and also involved, by some accounts, a plan to assassinate Hitler.

(#ulink_927639c0-7214-5267-b76b-7e90708537ad)

It is impossible to assess what was in Kennedy’s mind when he chose to casually brief American correspondents about the plot—and to provide the names of those involved. His blabbing can be seen most innocently as the actions of an ambitious man, eager to seem an insider, who would let nothing block his efforts to ingratiate himself with the press. But there is a far darker interpretation. The British Foreign Office’s Kennediana files, which were made public after the war, show that Kennedy was opposed to any policy based on the assassination of Adolf Hitler, in fear that Hitler’s death would leave Soviet communism unchecked. In late September of 1939, three weeks after Hitler’s invasion of Poland, Kennedy directly raised his concerns in a conference with Lord Halifax, the British foreign secretary. Halifax quoted Kennedy as stating that he

himself was disposed to deprecate perpetual reference to the personal elimination of Hitler. How could we be sure that it would not have precisely the opposite effect on German feeling? … According to Mr. Kennedy, United States opinion thought that Russia was a much greater potential disturber of world peace through Communist doctrine than was Germany. He thought that American opinion would inevitably be greatly disturbed if and when it came to think that the result of the present struggle was a greater extension of bolshevism in Europe.… He appreciated the strength of British opinion about Hitler and the Nazi system, but, if the end of it all was to be universal bankruptcy, the outlook was very black.

Halifax, according to his Foreign Office note, did not respond to Kennedy’s comment about Hitler’s assassination.

(#ulink_cf851948-42cd-5ed9-8b7d-fd48a9c13a1f)

During his years in London, Joe Kennedy compounded his political and personal problems with FDR and his senior advisers through his overriding presidential ambition and his clumsy attempts to mask it. “He thought he was about the most qualified individual on earth to be president,” Klemmer said in his 1992 television interview. “He had supreme self-confidence, of course, as everybody knows, and he thought the monetary system in the United States needed revising and … one of his ambitions was to revise the whole monetary system.” Kennedy spent much time masterminding a campaign—transparent to the men in the White House—for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1940. The Kennedy claque of newspaper sycophants, headed by Arthur Krock, repeatedly planted stories about a possible Kennedy candidacy. Krock’s columns in the New York Times made the men in the White House gag. In a diary entry dated May 22, 1939, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau described how Thomas G. Corcoran, one of Roosevelt’s senior political advisers, “got really violent” while discussing Kennedy and Krock. “He said that Krock was running a campaign to put Joe Kennedy over for President.”

(#ulink_55159cb9-2889-5e60-8bb5-3bdaf79552da) Krock was further described as “the number one Poison at the White House.” Harold Ickes had earlier expressed concern about Kennedy’s qualifications, and his ambitions, in his diary: “At a time when we should be sending the best that we have to Great Britain, we have not done so. We have sent a rich man, untrained in diplomacy, unlearned in history and politics, who is a great publicity hound and who is apparently ambitious to be the first Catholic President of the United States.”

Roosevelt, who had every intention of running for an unprecedented third term in 1940, was just as skilled as Kennedy at planting stories. Walter Trohan, the crusty bureau chief of the Chicago Tribune, who was known to be close to Kennedy, recalled being summoned to the White House by Steve Early, Roosevelt’s press secretary, and given a challenge. “‘You’re a friend of Joe Kennedy’s, aren’t you?’ I said, ‘Yes, I like Joe.’ He said, ‘You wouldn’t criticize him?’ I said, ‘Oh yes, I would. I’d criticize any New Dealer. What’s Joe done?’” Early then gave Trohan copies of two Kennedy letters. The first, Trohan told me in a 1997 interview for this book, was addressed to Arthur Krock and said, “We ought not to get into the war.” The second, sent to the State Department, “was extremely pro-British and suggested getting along with Britain.” Trohan wrote an account of Kennedy’s gamesmanship for the Tribune. A few weeks later, Kennedy was called to Washington for a meeting. “He ran into me,” Trohan said, “and drew his hand across his throat. Joe knew I got the information from the White House.” The ambassador, Trohan added, “forgave me in the long run.”

FDR reacted to the political and diplomatic dangers posed by Kennedy by keeping him in London and increasingly isolating him from the American public and from all important policy decisions. The president sent a series of personal representatives to Great Britain in mid-1940, after Hitler invaded Denmark and Norway and began his drive into the Netherlands and Belgium toward France, and instructed them to make on-the-scene surveys of British morale and military readiness. Men such as Colonel William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, Colonel Carl Spaatz, General George Strong, and Admiral Robert L. Ghormley arrived in London, did their business, and returned to Washington—with little or no contact with the embassy, to Kennedy’s embarrassment and rage. By that time, too, much more of America’s business with England was being handled directly by the British Foreign Ministry, headed by Lord Halifax, including a highly sensitive proposal to swap long-term American leases on British overseas bases for fifty much-needed American destroyers. With war being waged throughout Europe, American diplomacy in Europe was made the primary responsibility of Ambassador William C. Bullitt in Paris, a Roosevelt confidant who shared FDR’s contempt for Nazi Germany.

(#ulink_d7bbe444-21ab-562e-afaa-6f0124362d1b)

Kennedy understood that Roosevelt, despite his many public statements to the contrary, was intent on bringing America into the war. The president had begun an intermittent secret correspondence with Winston Churchill in the fall of 1939, nine months before Churchill was named prime minister. The two men were careful, even in their encrypted communications, not to talk openly about taking on Hitler together, but they did agree to work out procedures for sharing, among other intelligence, the location of German submarines and surface ships. Such exchanges would have provoked, at the least, an outcry among the isolationists in Congress and imperiled Roosevelt’s reelection prospects. No copies of the sensitive communications were to be made available to the British Foreign Office; the two leaders communicated via the code room in the American Embassy—Joe Kennedy’s embassy.

(#ulink_4b02e6f0-63d6-5ad8-8264-6efe9de43a78) Kennedy remained insensitive, at best, about the Jewish issue through the later war years, when the existence of concentration camps was widely known. In a May 1944 interview with an old friend, Joe Dinneen of the Boston Globe, Kennedy acknowledged, when questioned about his alleged anti-Semitism: “It is true that I have a low opinion of some Jews in public office and in private life. That does not mean that I hate all Jews; that I believe they should be wiped off the face of the earth.… Other races have their own problems to solve. They’re glad to give the Jews a lift and help them along the way toward tolerance, but they’re not going to drop everything and solve the problems of the Jews for them. Jews who take an unfair advantage of the fact that theirs is a persecuted race do not help much.… Publicizing unjust attacks upon the Jews may help to cure the injustice, but continually publicizing the whole problem only serves to keep it alive in the public mind.” Kennedy’s discussion of anti-Semitism was withheld from publication at the time by the editors of the Globe, but in 1959 Dinneen sought to include a portion of it in a generally flattering precampaign family biography. Advance galleys of the Dinneen book, entitled The Kennedy Family, had been given to Jack Kennedy, who understood how inflammatory his father’s comments would be and had no difficulty in successfully urging Dinneen to delete the offending paragraphs. The incident is described in Richard Whalen’s biography of Joe Kennedy.

(#ulink_bf1b649d-b451-58b8-a644-3f16ee0c808e) Beck resigned as chief of staff in protest against Hitler’s plan to invade Czechoslovakia, and was involved in a series of plots against Hitler for the next six years. He shot himself after the failure of Count Claus von Stauffenberg’s final attempt to assassinate Hitler, by bomb, on July 20, 1944. Halder, who served as chief of staff until September 1942, was arrested in the Gestapo’s widespread roundup after the 1944 bomb attempt and placed in a concentration camp. He survived the war.

(#ulink_589d6bf1-2379-57aa-b8ff-f073856e4106) Even Rose Kennedy knew something was up. In her gossipy memoir, Times to Remember, she described an early 1939 lunch at 10 Downing Street at which she asked Chamberlain “if Hitler died would he be more confident about peace, and he said he would.” Rose defended her husband’s contrary view in her memoir, published in 1974, insisting that “of course, no one knew then that Hitler was criminally insane and had no intention of living by humane standards except his own demented ones, and that his promises meant nothing to him.” In Mrs. Kennedy’s view, presumably, “no one” would not include the millions of Jews who were being systematically persecuted throughout Germany and German-occupied Central Europe by 1939.

(#ulink_473fc038-27a5-5081-b440-a83b09e79fc8) In an interview in 1962 with Richard J. Whalen, Corcoran depicted Kennedy, with grudging admiration, as having staged a “remarkable coup d’état” in putting his son into the presidency. “You have to look at this piece of energy adapting itself to its time,” Corcoran said. “A man not afraid to think in a daring way. He had imperial instinct. He knew what he wanted—money and status for his family. What other end is there but power?” Jack Kennedy’s election in 1960 was a “long-shot risk,” Corcoran added, into which Joe Kennedy “slammed money.… These are not the attributes of the philosopher, the humanitarian, educators or priests. These are the attributes of those in command.”

(#ulink_707d350a-c4c1-56d1-a2f0-7bfd996b967d) Bullitt and the president were briefly put on the defensive in late March 1940, when the German Foreign Office released a series of diplomatic documents that had been found in Polish archives after the seizure of Warsaw the previous September. In a private conversation in November 1938, Bullitt was said by Count Jerzy Potocki, the Polish ambassador to Washington, to have expressed “great vehemence and strong hatred about Germany and Chancellor Hitler. He said only strength, and that at the conclusion of a war, could make an end of the mad expansion of the Germans in the future.” In a talk a few weeks later, Bullitt was said to have given the Poles “moral assurance that the United States will leave its isolationist policy and be prepared in the event of war to participate actively on the side of France and Britain.” The White House quickly characterized the documents as propaganda and put out a statement, in Roosevelt’s name, urging that they “be taken with several grains of salt.” Over the next few days, however, reporters in Berlin were shown the documents in question and found them to have all the appearance of being genuine. One set of the Polish papers released by the Germans dealt with an interview with Joseph Kennedy, who, in a June 1939 talk with Jan Wszelaki, a Polish trade official, was quoted as boasting that his two eldest sons, Joseph and John, had recently traveled all over Europe and “intended to make a series of lectures on the European situation … after their return to the United States, at Harvard University … ‘You have no idea,’” Wszelaki further quoted Kennedy as telling him, “‘to what extent my oldest boy … has the President’s ear. I might say that the President believes him more than me.’”

6 TAKING ON FDR (#ulink_81d0901e-b8af-5011-afde-10cf05f0d043)

By early October 1940, there was very bad blood between the president and his reluctant ambassador in England. Kennedy wanted out and he didn’t care who knew it. On October 10, he took advantage of a farewell meeting in London with Foreign Minister Halifax to issue a warning to Roosevelt—correctly anticipating that the British Foreign Office would relay the threat to the State Department via the British Embassy in Washington. “His principal complaint,” Halifax reported to the British ambassador, Lord Lothian, was that

they had not kept him adequately informed of their policy and doings during the last two or three months.… He told me that he had sent an article to the United States to appear on November 1st, if by any accident he was not able to get there, which would be of considerable importance appearing five days before the Presidential election. When I asked him what would be the main burden of his song, he gave me to understand that it would be an indictment of President Roosevelt’s administration for having talked a lot and done very little. He is plainly a very disappointed and rather embittered man.

Kennedy was more than embittered; he was in a rage. “I’m going back and tell the truth. I’m going home and tell the American people that that son of a bitch in the White House is going to kill their sons,” he told Harvey Klemmer over lunch on the day before he left London, as Klemmer recounted in the television interview made available for this book.

Arthur Krock, Kennedy’s faithful scribe, provided a detailed account of Kennedy’s blackmail plottings in his Memoirs:

On October 16 Kennedy sent a cablegram to the President insisting that he be allowed to come home.… That same day Kennedy telephoned … and said that if he did not get a favorable reply to his cablegram, he was coming home anyhow; … that he had written a full account of the facts to Edward Moore, his secretary in New York, with instructions to release the story to the press if the Ambassador were not back in New York by a certain date. A few hours after this conversation the cabled permission to return was received.

Kennedy’s “full account” referred to the extensive exchange of cables between Roosevelt and Churchill that had been relayed through the American Embassy. Those secret cables had a secret history known to only a few in America and England in the spring of 1940. Kennedy had been shocked in May when a special unit of British counterintelligence staged a late-night raid on the apartment of Tyler Kent, an American Embassy code clerk, and uncovered a cache of more than 1,500 decoded diplomatic cables that Kent had taken home. Kennedy took the unusual step of immediately revoking Kent’s diplomatic immunity—State Department immunity has never been revoked since—and Kent was secretly tried and convicted in a London court. He spent the war years in an isolated British prison on the Isle of Wight.

Kennedy’s decisive action to keep Kent’s betrayal of his nation—as well as the Roosevelt-Churchill correspondence—from becoming public has been credited by historians as high-minded and exemplary. Had this not been done, Kent could have been tried in America; his documents would become part of the court record, triggering anger and resentment in the Congress and among the many Americans opposed to U.S. involvement in the war in Europe. The furor, the historian Michael Beschloss wrote in his Kennedy and Roosevelt: The Uneasy Alliance, published in 1980, “might have eliminated any chance of a third term for the president and made it nearly impossible for him to move public opinion so swiftly toward aid to the Allies.… [Kennedy] was unwilling to influence American policy at the cost of an act that seemed illegitimate and disloyal.”

Kennedy had much more to gain, however, by making private use of the Tyler Kent materials in his war against FDR. American Embassy files show that on May 20, 1940, the day of Kent’s arrest, Ambassador Kennedy arranged to ship a diplomatic pouch full of “personal mail and various packages” to Washington, in the care of a friend in the State Department. On May 23, three days after Kent’s arrest, Kennedy sought and received authorization from the State Department for Edward Moore, his exceedingly faithful personal assistant, to return to New York with Rose Kennedy and their retarded daughter, Rosemary. Moore left London on May 28 and never went back.

Tyler Kent, obsessed with hatred for Kennedy, lived in obscurity after the war as a gentleman farmer in rural Maryland. The FBI files on his case remained secret until 1982, when the British journalist John Costello, an expert on World War II history, obtained them under the Freedom of Information Act. Costello, who died in 1995, also obtained scores of State Department documents on the Kent affair, including many of Ambassador Kennedy’s cables to Washington. Costello approached Kent, who was intrigued by the newly released documents and agreed to a series of detailed interviews. In those interviews, Kent is quoted as explaining that his interest in the secret cables had been aroused only after Kennedy ordered him “to make copies of nonroutine messages that went in and out of the embassy for Kennedy’s personal file.” Kennedy also instructed Kent to retrieve all of Roosevelt’s coded exchanges, dating back to the 1938 Munich accord, with Ambassador William C. Bullitt in Paris and with the other ambassador widely known to be avidly anti-Hitler, Anthony Drexel Biddle, in Warsaw.

(#ulink_a1b8f60f-1e3c-5777-8e81-70cfe8f5de0b)

The Kent matter languished until later in the 1980s, when Robert T. Crowley, a counterintelligence officer who specialized in Soviet penetrations of the West, retired from the Central Intelligence Agency. “There were a couple of guys left over when I retired, and one was Kent,” Crowley recalled in an interview for this book. “I thought the guy was unstable” and a possible Soviet KGB agent. As a former CIA officer, Crowley had connections. Over the next few years he was able to obtain access to previously unavailable government files on Tyler Kent. The Kent-KGB spy story soon petered out, Crowley said: “Tyler never developed into anything we thought. We couldn’t demonstrate that he was working for the Soviets, or the Germans, or the Italians. He was working for Tyler—and he’s trying to save the United States from Roosevelt. He was everybody’s tool. Just a kooky half-wit.” But Crowley did find documentation, he told me, that convinced him that Kennedy had been assembling a political dossier on FDR, and was using Kent to get access to the potentially damaging Roosevelt-Churchill cables.

In Crowley’s view, Kennedy’s refusal of diplomatic immunity to Kent, thus assuring that he would be held without access to the American press, was a brilliant move. Kennedy made another brilliant move, Crowley said; he arranged to ship his copies of the sensitive and politically incriminating Churchill-Roosevelt cablegrams to America. Edward Moore, once in America, could retrieve the copies and prepare for the coming showdown with Roosevelt. The cablegrams, Crowley told me, “put Kennedy in a marvelous position with FDR. He had him in a spot and could possibly deny him his reelection. He had a knife.”

Joe Kennedy declared war on the White House. Historians agree on what happened next: Kennedy arrived in Washington on the evening of October 26, amid much press speculation that he was planning to endorse Wendell Willkie, the Republican candidate. The election was only ten days away. Kennedy’s flight from London had been delayed for days by poor weather, and en route he received a series of urgent and confidential messages from FDR inviting him to dinner at the White House. The two men talked early on the twenty-sixth—Kennedy was then in Bermuda, on the last leg of his Pan Am Clipper flight to New York—and Roosevelt’s side of the conversation was overheard by Lyndon Baines Johnson, then an ambitious young congressman from Texas, who happened to be visiting the Oval Office. “Ah, Joe,” the president said, “it is so good to hear your voice. Please come to the White House tonight for a little family dinner.” Over the years, Johnson would dramatically tell many journalists what happened next: FDR slowly drew his hand across his throat and added, “I’m dying to talk to you.”

Exactly what took place at the Kennedy-Roosevelt White House meeting may never be known. In Joe Kennedy’s much-quoted version, as relayed by him to Arthur Krock, FDR was at his most charming with Kennedy and his wife, who had been personally invited by Roosevelt to join her husband at dinner. There was the inevitable praise for Kennedy’s children and a presidential willingness to listen to Kennedy’s complaints about the way he had been ignored and mistreated while in London. Roosevelt claimed, according to the account in Krock’s memoir, that “he had known nothing about these matters; the fault lay with the State Department.” FDR’s sweet-talking prevailed, according to Krock. Temporarily smitten, Kennedy agreed to make a radio speech calling for Roosevelt’s reelection.

That explanation, given the well-documented and high level of hostility between the president and his ambassador, is simply not believable. In later years, Kennedy provided at least two different reasons for his turnabout. He told the journalist Stewart Alsop that the president had held out the hope that a strong endorsement in the radio talk could lead to FDR’s backing for a Kennedy presidential campaign in 1944. And Kennedy explained to Clare Boothe Luce, wife of his longtime friend Henry Luce, publisher of Time magazine, that “we agreed that if I endorsed him for president in 1940, then he would support my son Joe for governor of Massachusetts in 1942.” Kennedy and Roosevelt viewed each other as consummate liars, so a presidential promise of future support—even if one was, in fact, proffered—would have meant little.