По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

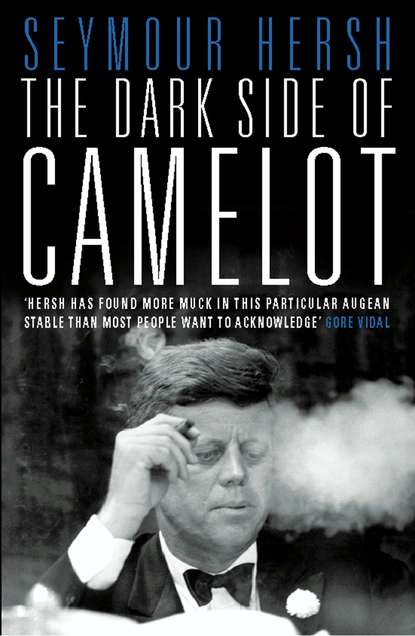

The Dark Side of Camelot

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Buying votes was nothing new in West Virginia, where political control was tightly held by sheriffs or political committeemen in each of the state’s fifty-five counties. Their control was abetted by the enormous number of candidates who competed for local office in the Democratic primary, resulting in huge paper ballots that made voting a potentially interminable process. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the 1960 campaign, The Making of the President, 1960, the journalist Theodore H. White noted that the primary ballots for Kanawha County, largest in the state, filled three full pages when published the day before in the Charleston Gazette. Sheriffs and other political leaders in each county made the process less bewildering for voters by putting together lists, or slates, of approved party candidates for each office. Some candidates for statewide offices or for important local posts, such as sheriff or assessor, invariably ended up on two, three, or more slates passed out on election day by campaign workers. The unwieldy procedure continues today.

The sheriffs and party leaders were also responsible for hiring precinct workers and poll watchers for election day. Political tradition in the state called for the statewide candidates to pay some or all of the county’s election expenses in return for being placed at the top of a political leader’s slate. Paying a few dollars per vote on election day was widespread in some areas, as was the payment for “Lever Brothers” (named after the popular detergent maker)—election officers in various precincts who were instructed to actually walk into the ballot booth with voters and cast their ballots for them.

The Journal’s investigative team, which included Roscoe C. Born, of the Washington bureau, spent the next five weeks in May and June in West Virginia and learned that the Kennedys had turned what had historically been random election fraud into a statewide pattern of corruption, and had apparently stolen the election from Hubert Humphrey. The reporters concluded that huge sums of Kennedy money had been funneled into the state, much of it from Chicago, where R. Sargent Shriver, a Chicagoan who had married Jack’s sister Eunice in 1953, represented the family’s business interests. The reporters were told that much of the money had been delivered by a longtime Shriver friend named James B. McCahey, Jr., who was president of a Chicago coal company that held contracts for delivering coal to the city’s public school system. As a coal buyer earlier in his career, McCahey had spent time traveling through West Virginia, whose mines routinely produced more than 100 million tons of coal a year. Roscoe Born and a colleague traveled to Chicago to interview McCahey “and he snowed us completely,” Born recalled in a series of interviews for this book. Nonetheless, the reporter said, “there was no doubt in my mind that [Kennedy] money was dispensed to local machines where they controlled the votes.”

Born, convinced that he and his colleagues had collected enough information to write a devastating exposé, moved with his typewriter into a hotel near the Journal’s office in downtown Washington. He was facing a stringent deadline—the Democratic convention was only a few weeks away—and also a great deal of unease among the newspaper’s senior editors.

As with many investigative newspaper stories, there was no smoking gun: none of the newspaper’s sources reported seeing a representative of the Kennedy campaign give money to a West Virginian. “We knew they were meeting,” Otten recalled in our interview, “but we had nothing showing the actual handing over of money.” The Journal’s top editors asked for affidavits from some of the sources who were to be quoted in the exposé; when the journalists could not obtain them, the editors ruled that the article could not be published. “The story could have been written, but we’d have to imply, rather than nail down, some elements,” Born said. “I really wanted to do it, but I can see that the editors would be nervous about doing it practically on the eve of the convention.” Other Journal reporters were told that Born and his colleagues had “gotten the goods,” as one put it, on the Kennedy spending in West Virginia. The columnist Robert D. Novak, then a political reporter on the Journal, recalled in an interview for this book hearing that the newspaper’s top management had concluded that the West Virginia money story could affect the proceedings in Los Angeles, and it was not “the place of the Wall Street Journal to determine the Democratic nominee for president.”

The Journal’s reporting team was far closer to the truth than its editors could imagine. Jack Kennedy had wanted a clean sweep in the April 5 Democratic primary in Wisconsin, aiming to defeat Hubert Humphrey in all ten of the state’s congressional districts, and he campaigned long hours to get one. He was bitterly disappointed when he won only six districts—and, most important, when his showing failed to discourage the equally hardworking Humphrey, who decided to continue his presidential campaigning in West Virginia. It was understood by professional politicians that Humphrey, too, would be putting in as much money as he could to meet the inevitable bribery demands of the county sheriffs. The Kennedy team also feared that other Democratic opponents for the nomination, Lyndon Johnson and Adlai Stevenson among them, would urge their backers to shove money into the state on Humphrey’s behalf in an effort to stop Kennedy and deadlock the convention.

(#ulink_44b1fec5-9481-59b1-bb41-18a8e7cce328)

West Virginia thus became the ultimate battleground for the Democratic nomination, and the Kennedys threw every family member and prominent friend they had, and many dollars, at defeating Humphrey. At stake was not only Jack’s presidency, but Joe Kennedy’s dream of a family dynasty: Bobby was to be his brother’s successor.

In interviews for this book, many West Virginia county and state officials revealed that the Kennedy family spent upward of $2 million in bribes and other payoffs before the May 10, 1960, primary, with some sheriffs in key counties collecting more than $50,000 apiece in cash in return for placing Kennedy’s name at the top of their election slate. Much of the money was distributed personally by Bobby and Teddy Kennedy. The Kennedy campaign would publicly claim after the convention that only $100,000 had been spent in West Virginia (out of a total of $912,500 in expenses for the entire campaign). But what went on in West Virginia was no secret to those on the inside. In his 1978 memoir, In Search of History, Theodore White wrote what he had not written in his book on the 1960 campaign—that both Humphrey and Kennedy were buying votes in West Virginia. White also acknowledged in the memoir that his strong affection for Kennedy had turned him, and many of his colleagues, from objective journalists to members of a loyal claque. White stayed in the claque to the end, claiming in his memoir, without any apparent evidence, that “Kennedy’s vote-buyers were evenly matched with Humphrey’s.”

In later years, even the most loyal of the loyalists acknowledged what happened in the West Virginia primary. In one of her interviews in 1994, Evelyn Lincoln said, “I know they bought the election.” And Jerry Bruno, who served as one of Kennedy’s most dependable advance men in the 1960 campaign, similarly said in an interview: “Every time I’d walk into a town [in West Virginia], they thought I was a bagman. They used to move polling places if you didn’t give them the money. We didn’t do it better, but we got the people who at least were half-honest. The Hubert people—they’d take the money and then come to see us.”

The most compelling evidence was supplied by James McCahey, the Chicago coal buyer, who refused to cooperate with the Wall Street Journal in 1960. In a 1996 interview for this book, he revealed that the political payoffs in West Virginia had begun in October 1959, when young Teddy Kennedy traveled across the state distributing cash to the Democratic committeeman in each county. McCahey was told later that the payoffs amounted to $5,000 per committeeman, a total expenditure of roughly $275,000. McCahey, who left the coal business in Chicago for the railroad business (he retired in 1985 as a senior vice president of the Chessie System Railroads, in Cleveland), added that the Wall Street Journal’s suspicions of him were wrong: his assignment in West Virginia had not been to make payoffs but to organize the teachers in each county “and help them get out the word about Kennedy.” Through this assignment he was able to learn a great deal about what was going on in the state.

McCahey, a major fund-raiser in 1960 for Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago, was also a strong Kennedy supporter and had been assigned to direct the Kennedy campaign in the southern districts of Wisconsin. After the disappointing results there, McCahey told me, Sargent Shriver telephoned and invited him to an important insiders strategy meeting in Huntington, West Virginia, that had been put together by Jack and Bobby Kennedy, and included Jack’s brother-in-law Stephen Smith, the campaign’s finance director. New polling was showing a precipitous drop in support for Kennedy among West Virginians; the subject of the meeting was how to get the campaign back on track. It was then, McCahey said, that he learned about Teddy Kennedy’s efforts the previous fall to pay for support from the county committeemen.

“It didn’t work at all,” McCahey told me. “You don’t go into a primary [in West Virginia] and spread money around to committeemen. The local committeeman will take your money and do nothing. The sheriff is the important guy” in each county. “You give it to the sheriff. That’s the name you see on the political banners when you go into a town.” McCahey further recalled being told at the meeting that Joe Kennedy believed that the buying of sheriffs “was the way to do it.”

The sheriffs, it was understood, had enormous discretion in the handling of the cash. Some would generously apportion the cash to their supporters; others would pocket most of the money.

McCahey recalled that his essential contribution was to tell the Kennedys “to forget what you’ve done and start again. I laid out a plan”—to organize teachers and other grassroots workers—“and they said go.” He also worked closely with Shriver in visiting the major coal-producing companies in the state, all of which he knew well from his days as a buyer. “I’d drop into the local coal places and ask the fellows, ‘What’s going on?’” McCahey acknowledged passing out some cash to local political leaders while at work in West Virginia, paying as much as $2,000 for storefront rentals and for hiring cars to bring voters to the polls on primary day. He knew that far larger sums of money were paid to the sheriffs in the last weeks of the campaign. “If they did spend two million dollars,” McCahey told me, with a laugh, in response to a question, “they figured, ‘Hell, let McCahey go [with his plan to organize teachers and the like].’ They had lots of angles.”

There is evidence that Robert Kennedy was, as Teddy had been earlier, a paymaster in the hectic weeks before the May 10 primary. Victor Gabriel, of Clarksburg, a supervisor for the West Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission who ran the Kennedy campaign that spring in Harrison County, recalled in an interview for this book a meeting before the election with Bobby and the ever-loyal Charles Spalding. Gabriel told the two men that he needed only $5,000 in election-day expenses to win the county for them. The exceedingly low estimate, Gabriel told me, caused Spalding to exclaim, “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Gabriel, eighty-two years old when interviewed in 1996, refused to take any more cash and delivered his county, as promised, on election night. Gabriel joined other Kennedy workers at a gala victory celebration at the Kanawha Hotel in Charleston. At some point during the party, he said, a grateful Bobby Kennedy ushered him into the privacy of a bathroom and pulled out a little black book. “You could have gotten this,” Kennedy told him, as he pointed to a page in the book, “to get people on the bandwagon.” Kennedy’s notebook showed that as much as $40,000 had been given to Sid Christie, an attorney who was the top Democrat of McDowell County, in the heart of the state’s coal belt in the south. The Kennedy notebook made it clear, Gabriel told me, that the campaign had “spent a bundle” to get the all-important support of all the sheriffs and political leaders in the south.

Gabriel told me that he had no second thoughts about the relatively small amount of Kennedy money he had requested. “I told [Bobby] what I needed and didn’t take a damn dime more,” Gabriel said. “All I had to do was tell him fifteen thousand or twenty thousand, instead of five thousand, and I’d have got it. But I don’t operate that way. If you’re going to be for a man, be for him.” The sheriffs who took more than $5,000, Gabriel told me, were simply pocketing the money.

Two former state officials acknowledged during 1995 interviews for this book that they also knew of large-scale Kennedy spending.

Bonn Brown of Elkins was the personal attorney to W. W. “Wally” Barron, who was elected Democratic governor of West Virginia in 1960. He estimated the Kennedy outlay at between $3 million and $5 million, with some sheriffs being paid as much as $50,000. Asked how he knew, Brown told me curtly, “I know. If you don’t get those guys”—the sheriffs—“they will really fight you.” In his role as adviser to the Democratic gubernatorial candidate, Brown met with Robert Kennedy and other campaign officials “and told them who to see and what to do, but stayed clear of it myself. Bobby was smart and mean as a snake. I think he had more to do with West Virginia”—the victory there, and the payoffs—“than any other person. Bobby ran it; he was the one who set it up.” Governor Barron was later convicted on bribery charges, and Brown was later convicted of the attempted bribery of a juror in the case.

Curtis B. Trent, of Charleston, who served as executive assistant to Governor Barron, also recalled that the Kennedys “were spreading it around pretty heavy. I thought they spent two million dollars.” Trent, like Bonn Brown, insisted that he did not personally take any Kennedy money. “They were trying to push it off on us,” he recalled. “I’d explain to them that I was concerned with the governor’s race and not the president’s race.” Kennedy reacted typically to Trent’s refusal to help: “Bobby was so mad … just as angry as he could be.” Trent, like more than a dozen officials of the Barron administration, the most corrupt in the history of the state, was convicted of income tax evasion and sentenced to a jail term in 1969.

The Gabriel, Brown, and Trent accounts are buttressed by Rein Vander Zee, a former FBI agent who had been working since early January 1960 in Humphrey’s West Virginia campaign. Vander Zee was responsible for dealing with the sheriffs of West Virginia, and had—for a price—received their political commitments for Humphrey. “Four or five days before the primary,” Vander Zee, now living in Bandera, Texas, told me in an interview in 1995, “I couldn’t get some of my people on the phone. I said, ‘Oh, my God,’ and got in my car and started driving. They were laying out—the sheriffs—and I knew something was way wrong. The Humphrey signs were down and Kennedy signs were up. I met Sid Christie, who was supposed to be our man [in McDowell County] all the way. He was the absolute boss down there.” Vander Zee arranged a meeting with Christie in the rural town of Keystone. “We sat in his car across from a deserted movie theater, like a scene from The Last Picture Show. I said, ‘What can be done?’” Christie dryly responded: “It’s too late. I didn’t realize what a groundswell of support there’d be for this other fellow.”

Vander Zee said he and Humphrey later held a last-ditch conference with Wally Barron, the governor-to-be: “We asked him what had to be done. I always liked Wally.” Barron gave Humphrey the bad news: he was being vastly outspent by the Kennedys. “He said he had a figure [of Kennedy expenditures] that was something we couldn’t meet,” Vander Zee said. Years later, a West Virginia political professional told Vander Zee that he watched as Christie received a huge payoff from a Kennedy insider—at least $40,000, the professional said—“in green in a shoe box.” Kennedy received 84 percent of the Democratic primary vote on May 10 in McDowell County.

In the years after Kennedy’s assassination, many people would take credit for his strong showing in West Virginia.

In his autobiography, The Education of a Public Man, published in 1976, Hubert Humphrey told of a 1966 meeting with Richard Cardinal Cushing, the archbishop of Boston, in which Cushing expressed anger at what he called the self-aggrandizement of various Kennedy aides, such as Ted Sorensen. “I keep reading these books by the young men around Jack Kennedy and how they claim credit for electing him,” Cushing told Humphrey. “I’ll tell you who elected Jack Kennedy. It was his father, Joe, and me, right here in this room.” Humphrey and an aide sat in stunned silence as Cushing told how he and Joe Kennedy had agreed that West Virginia’s anti-Catholicism could be countered by a series of cash contributions to Protestant churches, particularly in the black community. Cushing continued, Humphrey wrote: “We decided which church and preacher would get two hundred dollars or one hundred dollars or five hundred dollars.”

The most widespread misinformation about the West Virginia election involves the role of organized crime, which, according to countless magazine articles and books over the past thirty years, supplied the cash that enabled Kennedy to win. The allegations center on Paul “Skinny” D’Amato, the New Jersey nightclub owner who in 1960 became general manager of a Nevada gambling lodge owned in part by Frank Sinatra and his good friend Sam Giancana of Chicago. D’Amato’s account, as repeatedly published, is that he was approached by Joe Kennedy during the primary campaign and asked to raise money for West Virginia. D’Amato agreed to do so, with one demand: if Jack Kennedy was successful in gaining the White House, he would reverse a 1956 federal deportation order for Joey Adonis, the New Jersey gang leader. With Joe Kennedy’s promise, D’Amato raised $50,000 for West Virginia from assorted gangsters. D’Amato, who died in 1984, has been quoted as telling a business associate that the $50,000 was used not for direct bribes but to purchase desks, chairs, and other supplies needed by local politicians. After Kennedy’s election, D’Amato said, he reminded Joe Kennedy of his pledge. The father explained that the Adonis deal was fine with his son the president, but Bobby, the new attorney general, wouldn’t hear of it. There is no basis for disbelieving D’Amato’s account; but $50,000 in cash, when contrasted with what was really spent in West Virginia, was hardly enough to earn everlasting gratitude from the Kennedys.

D’Amato’s big mouth got him in trouble. Soon after taking office, Bobby Kennedy was informed by the FBI that D’Amato had been overheard on a wiretap bragging about his role in moving cash from Las Vegas to help Jack Kennedy win the election. A few months later, D’Amato suddenly found himself facing federal indictment on income tax charges stemming from his failure to file a corporate tax return for his nightclub. The indictment was brought to the attention of Milton “Mickey” Rudin, a prominent Los Angeles lawyer who represented Frank Sinatra and other entertainment figures.

“Skinny [was] Frank’s friend,” Rudin told me in a series of interviews for this book. “Bobby [Kennedy] and the Old Man [Joe Kennedy] knew the relationship. When Skinny got indicted, I got pissed and called up Steve Smith. I tell him I want to see him. He meets me at the University Club in New York. I order my gin. ‘What can I do for you?’ Smith asks. I tell him, ‘I’m unhappy about Skinny being indicted on the bullshit charges. It’s unfair. No taxes were paid because there was no profit.’” Rudin said he did not raise the issue of D’Amato’s political favors for the Kennedy campaign, but he did tell Smith, “This is a political act.” Smith responded, “Well, you don’t understand politics.” Rudin then said, “Well, I’m glad I don’t,” drank his gin, and left.

Steve Smith delivered a clear message, Rudin said: D’Amato had been overheard on FBI wiretaps talking about Las Vegas cash going to the Kennedys, and the indictment neutralized any possible damage from such talk. “If some guy like Skinny had anything to do with moving money,” Rudin concluded, “the way to handle him is to indict him so if he talked about it, it’d be [seen as] vengeance.” Rudin told me that he returned to Los Angeles thinking—and saying as much to Sinatra and others—that the Kennedys were going to be much tougher than some had thought.

Organized crime, as we shall see, played a huge role in Kennedy’s narrow victory over Richard Nixon in November. But Jack Kennedy had more than a few campaign promises to gangsters to worry about, both before and after the election.

(#ulink_46b0b535-748e-58fc-ad9f-0068a6e7f970) Max Kampelman, Humphrey’s longtime friend and political adviser, recalled warning Humphrey not to run against Kennedy in West Virginia. In an interview in 1994, Kampelman said he “knew” that the Kennedys would put big money into the state and “steal the election—and we had no money.” An additional concern was Humphrey’s political future: “I told Hubert, ‘They’ll [the Kennedys will] kill you in West Virginia, and you have to run for reelection [to the Senate] in Minnesota. They’ll paint you as anti-Catholic, and there are a lot of Catholics in Minnesota.’” Humphrey nevertheless won reelection to the Senate in 1960.

8 THREATENED CANDIDACY (#ulink_4589d9fe-2c4f-5e50-abf1-567b43d02b35)

Jack Kennedy emerged from West Virginia as the man to beat, but there were still many dangers that threatened his drive for the presidency. At least four women could control his destiny. One of them was Marilyn Monroe, the American film goddess whose affair with Kennedy had begun sometime before the 1960 election and would continue after he went to the White House.

Like his father, Jack Kennedy had a special fondness for Hollywood celebrities. The celebrated and gifted Monroe, born Norma Jean Mortenson, emerged as a sex symbol in the early 1950s and worked her way through husbands, lovers, pills, liquor, and psychiatric hospitals until her death, apparently by accidental suicide, in August 1962. Some published accounts place the beginning of the Kennedy-Monroe relationship in the mid-1950s, as Monroe’s second marriage, to the baseball star Joe DiMaggio, was unraveling and she was beginning a romance with the playwright Arthur Miller, who would become her third husband. Her affair with Kennedy was by all accounts in full bloom as the presidential campaign was getting under way. Many of their rendezvous were at the Santa Monica home of Peter and Patricia Lawford, Kennedy’s brother-in-law and sister, who were Monroe’s close friends. There has been published speculation that Monroe became pregnant by Kennedy and had an abortion in Mexico; the full story may never be known, but accounts of her affair and abortion have been published again and again since her suicide and his murder.

In interviews for this book, longtime friends and associates of Monroe and Kennedy acknowledged that the two stars, who both enjoyed living on the edge, shared a powerful, and high-risk, attraction to each other. “She was a beautiful actress,” George Smathers, Kennedy’s closest friend in the Senate, told me. “Probably as pretty a woman as ever lived. And Jack—everybody knew he liked pretty girls. When he had the opportunity to meet Marilyn Monroe, why, he took advantage of it, and got to know her a little bit.” The attraction went beyond sex. Monroe had a quirky sense of humor and a tenacious desire to learn. “Marilyn made Jack laugh,” Patricia Newcomb, who worked as a publicist for Monroe in the early 1960s, explained in an interview for this book. There was also a family connection that went beyond the Lawfords. Charles Spalding, who was a trusted intimate of Kennedy’s by the late 1940s and remained so until the president’s assassination, clearly recalled a private visit by Monroe to the family enclave at Hyannis Port, where she was welcomed enthusiastically as a friend of Jack’s—even though he was married.

Monroe’s repeated crack-ups did not diminish her looks or her ability to appeal to men. “Marilyn Monroe was the ultimate glamour girl,” Vernon Scott, a longtime Hollywood reporter for United Press International, told me in an interview. “She was gorgeous and she was funny. She had more sex appeal than any woman I ever saw, and I’ve seen lots of them. She was probably every man’s dream of the kind of woman he’d like to spend the rest of his life with on a desert island. She was much smarter than people gave her credit for. She never did or said anything by accident.”

Monroe was said to be deeply in love with Kennedy. After her death, John Miner, head of the medical legal section of the Los Angeles district attorney’s office, was given confidential access to a stream-of-consciousness tape recording Monroe made at the recommendation of her psychoanalyst, Dr. Ralph Greenson, a few weeks earlier; Miner put together what he considered to be a near-verbatim transcript of the tape. After obtaining permission from the Greenson family, Miner ended thirty-five years of silence by making the transcript available for this book in 1997. Many of Monroe’s comments dealt with her sexuality; her extensive comments about her problems achieving orgasm—in very blunt language—were meant only for the analyst’s couch, but her lavish admiration for Jack Kennedy could have been read from a podium:

Marilyn Monroe is a soldier. Her commander-in-chief is the greatest and most powerful man in the world. The first duty of a soldier is to obey her commander-in-chief. He says do this, you do it. He says do that, you do it. This man is going to change our country. No child will go hungry, no person will sleep in the street and get his meals from garbage cans. People who can’t afford it will get good medical care. Industrial products will be the best in the world. No, I’m not talking utopia—that’s an illusion. But he will transform America today like Franklin Delano Roosevelt did in the Thirties. I tell you, Doctor, when he has finished his achievements he will take his place with Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Franklin Roosevelt as one of our great presidents. I’m glad he has Bobby. It’s like the Navy—the President is the captain and Bobby is his executive officer. Bobby would do absolutely anything for his brother and so would I. I will never embarrass him. As long as I have memory, I have John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Show business people who worked behind the scenes with Monroe described a hard edge beneath the glamour. There were repeated breakdowns and repeated threats to tell the world about her relationship with Kennedy—threats that could have damaged his candidacy, and threats that only increased after he got to the White House. “What happened,” George Smathers told me, “was that she, [like] naturally all women, would like to be close to the president. And then after he had been associated with her some, she began to ask for an opportunity to come to Washington and come to the White House and that sort of thing. That’s when Jack asked me to see what I could do to help him in that respect by talking to her.” Monroe, Smathers said without amplification, had “made some demands.” Smathers said he arranged for a mutual friend to “go talk to Marilyn Monroe about putting a bridle on herself and on her mouth and not talking too much, because it was getting to be a story around the country.” It had happened before. Charles Spalding recalled that at one point during the 1960 campaign, when Monroe was on a liquor and pill binge, Kennedy asked him to fly from New York to Los Angeles to make sure that she was okay—that is, to make sure that Monroe did not speak out of turn. “I got out there, and she was really sick,” Spalding told me. With Lawford’s help, “I got her to the hospital.”

Monroe’s instability posed a constant threat to Kennedy. Michael Selsman, one of Monroe’s publicists in the early 1960s, depicted her as “a loose cannon” who toggled between high-spirited charm and mean-spirited cruelty. “Sometimes she had to put on this costume of Marilyn Monroe. Otherwise, she was this other person, Norma Jean, who felt abused, put-upon, and unintelligent. As Marilyn Monroe, she had enormous power. As Norma Jean, she was a drug addict who wasn’t physically clean.”

Vernon Scott told me that the other, insecure Monroe “made herself known to me one night” after he had concluded a newspaper interview with her at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Scott had a date with his wife-to-be and, as he and Monroe continued to chat over two bottles of champagne, he began looking at his watch. Monroe noticed and asked if he was going out. Scott said yes. “And she said,” Scott recounted, “sniffling a little bit and feeling sorry for herself, that everybody had somebody else to go to, everybody had dates, except her. She said, ‘I’m Marilyn Monroe. Everybody thinks the phone rings all the time with men asking me out. Well, everybody’s afraid to date Marilyn Monroe or ask her for a date.’ And she began crying, with mascara running down her face. And her eyes were red and she looked like kind of a clown. Her nose was red. She began sobbing. I tried to cheer her up and told her that I was sure most men would be delighted to take her out. She said, ‘Well, they don’t have the nerve to call me, not the right ones. And once in a while I meet a nice guy, a really nice guy, and I know it’s going to work. He doesn’t have to be from Hollywood; he doesn’t have to be an actor. And we have a few drinks and we go to bed. Then I see his eyes glaze over and I can see it going through his mind: “Oh, my God. I’m going to fuck Marilyn Monroe,” and he can’t get it up.’ Then she started howling with misery over this. I just bent over double laughing. And she began pounding on me—‘It’s not funny.’

“But,” Scott told me, “this was not Marilyn Monroe. Norma Jean would never have allowed Marilyn to look like that, but she did this one time. So I saw [Norma Jean] as a frightened, insecure, young puppeteer that was running this machine known as Marilyn Monroe. It was very touching and somewhat sad. And I liked her all the more for it.”

Monroe’s affair with Kennedy was no secret in Hollywood. In early January 1961, before the inauguration, Michael Selsman was informed about the relationship. “It was the first thing I was told,” Selsman said. “We had to be careful with this. We had to protect her, we had to keep her [private life] out of print. It’d be disastrous for me. It wasn’t hard in those days. It was a different era. Today it would be impossible to keep anything resembling that a secret.” Patricia Newcomb, who worked in the same public relations office with Selsman, also recalled knowing that her client “had been with the president,” and added: “It never occurred to me to talk about it. I couldn’t do it.”

James Bacon, who spent much of his career covering Hollywood for the Associated Press, said in an interview for this book that Monroe, whom he had befriended early in her career, had given him a firsthand account of her relationship with Kennedy as early as the campaign. “She was very open about her affair with JFK,” Bacon told me. “In fact, I think Marilyn was in love with JFK.” Asked why he didn’t file a story about the affair, Bacon said that in those days, “before Watergate, reporters just didn’t go into that sort of thing. I’d have to have been under the bed in order to put it on the wire for the AP. There was no pact. It was just a matter of judgment on the part of the reporters.”

Bacon added that he understood Kennedy’s “fascination with Hollywood. This is where the beautiful girls are, you know, and that’s why JFK loved it out here. He was a man who was addicted to sex, and if you want sex, this is the place to come.”

Kennedy was placing his political well-being in the hands of a group of Hollywood actresses, reporters, and publicists. His confidence that the affair with Monroe would remain secret was all the more perplexing because he was, even before he declared his candidacy, the target of a letter-writing campaign by a middle-aged housewife named Florence M. Kater, who decided in 1959 that her mission in life would be to force the Washington press corps to deal with Kennedy’s womanizing. Kater learned more than she wanted to know about the senator’s personal life after renting an upstairs apartment in her Georgetown home to Pamela Turnure, an attractive aide in Kennedy’s Senate office. Kennedy and Turnure were conducting an indiscreet affair that involved many late-night and early-morning comings and goings, to Kater’s consternation. Turnure moved to another apartment a few blocks away. In late 1958 Kater ambushed Kennedy leaving the new apartment at three A.M. and took a photograph of the unhappy senator attempting to shield his face with a handkerchief.

The encounter rattled Kennedy, and he struck back. A few weeks later, Kater alleged, she and her husband were accosted on the street in front of her home by the angry Kennedy, who, waving his fore-finger, warned her “to stop bothering me. If you do it again,” Kater quoted Kennedy as saying, “or if either of you spread any lies about me, you will find yourself without a job.” Kennedy eventually asked James McInerney, the former Justice Department attorney who had been retained in 1953 by Joe Kennedy, to try to muzzle Kater; the loyal McInerney spent dozens of hours in an attempt to convince her to stop her campaign.

McInerney met seven times with Kater, she later wrote, but for once the usual Kennedy mix of glamour, power, and money didn’t work. In May of 1959, Kater mailed a copy of the photograph and an articulate letter describing her encounter with Kennedy to fifty prominent citizens in Washington and New York, including editors, syndicated columnists, and politicians. Her letter and photograph also ended up on the desk of J. Edgar Hoover, as similar letters would over the next four years. The FBI, of course, began keeping a file on Kater, one obtained under the Freedom of Information Act for this book. In the letter Kater explained that, as an Irish Catholic, she had been a “warm supporter” of Kennedy; she had taken the photograph in the belief that “shock treatment” was needed. “But Senator Kennedy thought his behavior was none of our business,” Kater wrote. “We think he’s wrong there; it’s part of the package when you’re a public figure running for the Presidency.”

Kater became even more obsessed as Kennedy neared the Democratic nomination, and she continued sending out scores of letters complaining that the senator was a hypocritical womanizer who was morally unfit to be president. Kater was not taken seriously by the national press corps, but she came close to attracting media attention. On May 14, 1960, just four days after Kennedy won the West Virginia primary, she approached him at a political rally at the University of Maryland carrying a placard with an enlarged snapshot of the early-morning scene outside Pamela Turnure’s apartment. Kennedy ignored her, but a photograph of the encounter was published in the next afternoon’s Washington Star, along with a brief story describing her as a heckler. Kennedy’s aides denounced the photograph on her placard as a fake, Kater later wrote, and no questions were ever asked of the candidate, although Kennedy’s ongoing relationship with Turnure was no secret to the reporters covering his campaign or to campaign aides.

For all his apparent anger at Kater, Kennedy seemed to enjoy the added tension. Spalding told me of his concern at the time about the immense political liabilities posed by his friend’s constant womanizing. “I used to think he was crazy to do this stuff.” The risks were obvious: Kennedy’s campaign stance as a practicing Catholic and a responsible husband and father would be fatally undercut by a sex scandal. Steeling his courage, Spalding raised the issue at one point with Kennedy. “Well, if you’re worried about this,” Kennedy responded, “let me show you these pictures.” The candidate then pulled out a series of photographs—those mailed by Kater—showing him leaving the Turnure apartment.