По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

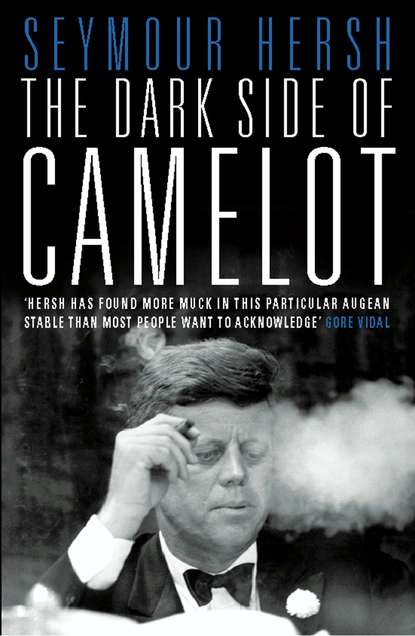

The Dark Side of Camelot

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A far more compelling reason for Kennedy’s decision to make the radio speech was provided by Winston Churchill’s son, Randolph, who in 1960 privately told the New York Times columnist C. L. Sulzberger that MI5 had provided Roosevelt with a collection of intercepted Kennedy cables and telephone calls in which the ambassador was critical of the president. The cables were passed to Brendan Bracken, Winston Churchill’s close friend and adviser, who, with Churchill’s approval, passed them along to FDR’s trusted aide Harry Hopkins. There is yet another version, which Joe Kennedy told Harvey Klemmer, who was surprised, as were many in London, at Kennedy’s last-minute endorsement of the despised Roosevelt. In his Thames TV interview, Klemmer recalled a later conversation with Kennedy about the radio address. “I said the press was speculating that FDR had dragged out an old tax return and said, ‘Joe, you wouldn’t want me to show this to the public, would you?’ And [Kennedy] said, ‘That’s a damn lie. I fixed that up long ago.’ So,” noted Klemmer, “there had been a tax mix-up at one time or another.”

Whatever the truth, the president and his ambassador had become two scorpions in a bottle: Kennedy could damage and perhaps destroy Roosevelt’s reelection chances by making public the Tyler Kent documents; Roosevelt, with Churchill’s help, had assembled an equally lethal dossier of telephone and cable intercepts. The full story lies buried, perhaps forever, in classified U.S. and British archives.

Kennedy’s half-hour radio speech on October 29 reassured Americans that the United States “must and will stay out of war.” No secret commitments had been made to the British by the Roosevelt administration, Kennedy said. And as for the oft-stated charge that the president was attempting “to involve this country in world war … such a charge is false.” The speech was jolting to those who knew what Kennedy really understood about Roosevelt’s war policy. In his memoirs, Arthur Krock noted: “The speech was out of keeping, not only with the wholly opposite view he had been expressing privately (to me, among others), but with Kennedy’s earned reputation as one of the most forthright men in public life.”

Three days after the election, Kennedy self-destructed. In an interview with Louis Lyons of the Boston Globe and two other journalists, he essentially declared that Hitler had won the war in Europe. “Democracy is finished in England,” Kennedy told Lyons. “Don’t let anybody tell you you can get used to incessant bombing. There’s nowhere in England they aren’t getting it.… It’s a question of how long England can hold out.… I’m willing to spend all I’ve got to keep us out of the war. There’s no sense in our getting in. We’d just be holding the bag.” The story made headlines. The American response was devastating for Kennedy: thousands of citizens wrote Roosevelt urging him to fire his defeatist ambassador. The British took it in stride, more astonished by Kennedy’s suicidal indiscretion in granting the interview than by its substance. Kennedy’s departure from London, during the Battle of Britain, with its nightly bombings and aerial dogfights, was seen by many as a cowardly retreat under fire. T. North Whitehead, one of the American specialists in the British Foreign Office, filed yet another caustic note in the office’s Kennediana file: “It rather looks as though he was thoroughly frightened when in London and has gone to pieces in consequence.”

The interview eroded Kennedy’s public support and ended his dreams of being elected to high public office in 1940. It also gave his enemies the courage to be his enemies.

Roosevelt finally lashed out at Kennedy after a private meeting with him at Thanksgiving; Kennedy was to be a weekend guest of the president and his wife at their estate at Hyde Park. It is not known precisely what took place, but Roosevelt ordered Kennedy to leave. Eleanor Roosevelt later told the writer Gore Vidal that she had never seen her husband so angry. Kennedy had been alone with the president no longer than ten minutes, Mrs. Roosevelt related, when an aide informed her that she was to go immediately to her husband’s office.

So I rushed into the office and there was Franklin, white as a sheet. He asked Mr. Kennedy to step outside and then he said, and his voice was shaking, “I never want to see that man again as long as I live. Get him out of here.” I said, “But, dear, you’ve invited him for the weekend, and we’ve got guests for lunch and the train doesn’t leave until two,” and Franklin said, “Then you drive him around Hyde Park and put him on that train.” And I did and it was the most dreadful four hours of my life.

Just what happened between the two men is not known, but Vidal, recounting the scene in a 1971 essay for the New York Review of Books, quoted Mrs. Roosevelt as wistfully adding, “I wonder if the true story of Joe Kennedy will ever be known.” (Discussing the scene years later, in an interview for this book, Vidal said he thought at the time that Mrs. Roosevelt’s real message was not only that the truth about Kennedy would not be known, but that it would be “too dangerous to tell.”)

Kennedy’s resignation as ambassador became official early in 1941. He would never serve in public office again.

Kennedy soon learned that having Roosevelt as an enemy meant having J. Edgar Hoover as an enemy, too. Published and private reports available to the White House and the British Foreign Ministry early in 1941 alleged that a notorious Wall Street speculator named Bernard E. “Ben” Smith had traveled to Vichy France in an attempt to revive an isolationist plan, favored by Kennedy, to provide Germany with a large gold loan in exchange for a pledge of peace. Kennedy, still intent on saving American capitalism from the ravages of war, was described in one British document as “doing everything in his power to try and bring this about.” Smith, known as “Sell ’Em Ben” in his Wall Street heyday, was identified as Kennedy’s emissary. In a confidential report to the Foreign Ministry dated February 4, Kennedy was reported to have sent Smith to visit senior officials of Vichy France in an effort to encourage “Hitler to try to find some formula for the reconstruction of Europe.… Having secured this, [Kennedy] hoped that, with the help of two prominent persons in England.… [he could] start an agitation in England in favour of a negotiated peace.” Roosevelt had learned of the Kennedy plan in advance, according to the Foreign Office report, and was able to abort it. Smith, a heavy contributor to Wendell Willkie’s presidential campaign, did travel to Vichy France in late 1940, but the plan went nowhere. On May 3, 1941, nonetheless, Hoover—getting his facts wrong—told Roosevelt that the FBI had learned from a “socially prominent” source that Kennedy and Smith had met secretly with Hermann Göring in Vichy, “and that thereafter Kennedy and Smith had donated a considerable amount of money to the German cause.” There was no evidence that Kennedy went to Europe with Smith, and no evidence that a meeting with Göring took place; but Hoover clearly understood that the discredited Kennedy was fair game—at least inside FDR’s White House.

By December 7, 1941, with Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and America finally in the war, it was over for Joe Kennedy. Caught up in his ambitions and his fears for the world economy, he had failed to see how Franklin Roosevelt connected to the American people. Kennedy, with his relentless social climbing and political scheming, had been on the wrong side of the greatest moral issue in his life—the need to stop Hitler’s Germany. It was a mistake his son Jack would not make.

Joe Kennedy’s political ambitions shifted, with a vengeance, to his two oldest sons, who would become his political surrogates, and would get the benefit of his money, intellect, and willingness to do anything. Joe Jr. was completing navy flight training in Jacksonville, Florida; Jack, a navy ensign, was assigned to the headquarters of the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington, where he was put to work writing daily and weekly intelligence bulletins.

Even with the war on, Jack Kennedy still managed to find time for partying. Just before the end of the year he initiated a torrid affair with a married Danish journalist, Inga Marie Arvad, who was estranged from her husband, a Hungarian movie director named Paul Fejos. Arvad, a former beauty queen, had interviewed Hitler and briefly socialized with him and other leading Nazis in 1936, while covering the Olympics for a Danish newspaper. She had been spotted by Arthur Krock while attending the Columbia School of Journalism in 1941. Krock recommended her to Frank Waldrop, the editor of the isolationist Washington Times-Herald, and Waldrop hired her to write a fluffy human interest column that focused on new arrivals to wartime Washington. Jack Kennedy was among those she interviewed. The handsome twenty-four-year-old navy officer fell in love with the older, more experienced, and far more sophisticated former beauty queen.

The FBI, alerted to Arvad’s meeting with Hitler by a jealous fellow reporter on the Times-Herald, marked her as a potential Nazi spy and began an investigation into her background. One early allegation, eventually discredited, was that Arvad’s uncle was a chief of police in Berlin. By early 1942, J. Edgar Hoover, at the direct insistence of FDR, became personally involved in the Arvad investigation. The next step was classic Hoover. Walter Winchell, firmly established as the FBI director’s favorite columnist, published the following item on January 12: “One of Ex-Ambassador Kennedy’s eligible sons is the target of a Washington gal columnist’s affections. So much so she has consulted her barrister about divorcing her exploring groom. Pa Kennedy no like.” A few days later, Hoover personally relayed a warning to Joe Kennedy, as JFK told it, that “Jack was in big trouble and he should get him out of Washington immediately.”

Eager to save his son’s career, Joe Kennedy arranged for Jack’s immediate transfer to a desk job at a base in Charleston, South Carolina. Jack continued, nonetheless, to meet with Arvad for the next two months, as the FBI—at Hoover’s direction—maintained round-the-clock surveillance, wiretapping her in Charleston and at her apartment in Washington. Agents even broke into her apartment to plant eavesdropping devices and to search through her papers and other belongings. No evidence linking Arvad to any wrongdoing was found, but the FBI—and Hoover—accumulated a large file of explicit tape recordings of the lovers at play. Joe Kennedy was overheard on the FBI wiretaps discussing politics with his son, who, the transcripts showed, was writing drafts of his father’s speeches. One FBI summary, as reported in JFK: Reckless Youth, by the British biographer Nigel Hamilton, showed that Joe Kennedy had political ambitions at an early stage not only for Joe Jr., as is widely known, but also for his second-born son. The FBI summary said Jack told Arvad that his father had stopped fully defending his very unpopular political positions in public “due to the fact that he believed it might hurt his two sons later in public.” The FBI wiretaps further showed that Arvad, while involved with Jack Kennedy, was also spending some nights with Bernard Baruch, the international financier and stock market speculator, who was close to the White House.

(#ulink_f0753833-a8ab-50d6-b9db-cb8053f389cc)

Young Kennedy’s involvement with Arvad dwindled by early March. Arvad got divorced in June 1942, moved to California, married the cowboy movie star Tim McCoy, and received her American citizenship. One of her references was Frank Waldrop, her former editor. In an unpublished essay written in 1978 and provided for this book, Waldrop, by then long retired, whimsically recalled how the much-ado-about-nothing FBI investigation had begun. A young female Times-Herald journalist who, wrote Waldrop, was Arvad’s rival for the attentions of the handsome Jack Kennedy, breathlessly informed him in the office one day that Arvad had been photographed in Hitler’s box during the 1936 Olympics. “That did it,” Waldrop wrote. “There was a row. So I took Inga by the elbow on one side and the other girl on the other and marched the pair of them over to the Washington field office of the FBI and told the agent in charge: ‘This young lady says that young lady is a German spy.’” At the time, Waldrop wrote, he did not know that a similar report by a fellow female student at the Columbia School of Journalism had been filed the previous year. “Nor did I guess what was going to happen next”—that a memorandum was sent by Roosevelt “directly to Hoover calling on him to have Inga ‘specially watched.’ How did FDR find out about Inga? Who broke in on his war planning to tell him about so trivial a matter, at the very time that the most critical moment of the war in the Pacific—the Battle of Midway—was in the making? I don’t know, though I have tried to find out.” In the end, Waldrop concluded, “Inga was no spy. Never had been. I have the official conclusions of the Department of Justice.”

(#ulink_2149fe89-3b1e-5e20-91b0-83fbfd3b80dc)

Waldrop’s assertions were confirmed in an interview with Cartha DeLoach, the FBI’s deputy director who worked closely with Hoover for nearly thirty years. “The investigation on Inga Arvad never conclusively proved that she was a German espionage agent,” DeLoach told me in 1997. “She had an amorous relationship with John F. Kennedy. And basically that’s what the files contained. She was never indicted, never brought into court, never convicted.”

Joe Kennedy understood what was going on. While some FBI field agents perhaps believed they were dealing with a true national security threat in the pretty Inga Arvad, the men at the top—Franklin Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover—were interested in payback, in reminding Joe Kennedy to stay in line and to remember that he was dealing with enemies who would be only too happy to hurt him. The FBI, as Joe Kennedy had to understand, had enough in its file on Jack Kennedy, complete with sound effects, to stop a future political career in its tracks.

Joe Kennedy knew what to do to safeguard his ambitions for his sons off at war. He had strayed from the church of Hoover and now sought redemption. In September 1943, Freedom of Information files show, Kennedy volunteered himself to the FBI bureau in Boston as a “Special Service Contact” and declared that “he would be glad to assist the Bureau in any way possible should his services be needed.” In a letter to Hoover, Edward A. Soucy, the agent in charge of the Boston Bureau, added: “Mr. Kennedy speaks very highly of the Bureau and the director, and has indicated that if he were ever in a position to make any official recommendations there would be one Federal investigative unit and that would be headed by J. Edgar Hoover.” A pleased Hoover accepted Kennedy’s offer and outlined, in a subsequent letter to Soucy, some of the requirements: “Every effort should be made to provide him [Kennedy] with investigative assignments in keeping with his particular ability and the Bureau should be advised as to the nature of these assignments, together with the results obtained.”

The full extent of Joe Kennedy’s machinations will never be known, but he left little to chance. The investigation into Inga Arvad and her relationship with Ensign Jack Kennedy had been supervised inside the Justice Department by James M. McInerney, who in 1942 was chief of the department’s national defense and internal security units. A former FBI agent, McInerney would remain in high policy positions in the Justice Department for the next ten years. In late 1952 McInerney successfully intervened to get Bobby Kennedy, just a year out of law school, a job as a staff attorney on the powerful Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. In 1953 McInerney went into the practice of law as a sole practitioner, opening up a small office on F Street in downtown Washington. Joe Kennedy and his three sons, Jack, Bobby, and Ted, were among his first clients, and they remained certainly his most important ones. Over the next decade, James McInerney would handle many sensitive matters on behalf of the Kennedy family and Jack Kennedy’s presidential ambitions. Women were seen, bribes were offered, and cases were settled—all in secrecy.

(#ulink_f411ac97-1c91-5c99-9b42-ed826d1b7d7d) Kent, after seeing Costello, kept on talking. In a separate interview later in 1982 with the BBC’s Newsnight television show, he explained how easy it had been to smuggle the cable traffic out of the embassy code room. One source, he told the journalist Richard Harris, was to obtain cable copies that were “surplus and were to be incinerated … burnt in an incinerator.… Another source was that Ambassador Kennedy was having copies of important political documents made for his own private collection. Part of my function was to make these copies, and it was quite simple to slip in an extra carbon.” The BBC show reported that Kent, described as an “amateur,” had been followed for eight months by British counterintelligence before his arrest.

(#ulink_41b8a1ee-392a-5660-bc00-0628ebaba969) Arvad’s nickname for Baruch, Frank Waldrop told me, was “the old goat.” Baruch could be very indiscreet, Waldrop wrote in an unpublished essay made available for this book, and the FBI agents assigned to wiretap the Arvad apartment gossiped about Baruch’s many telephone conversations with her. During the early years of the war, Waldrop said, he often traded gossip with the old financier, sometimes over lunch on a bench in Lafayette Park, near the White House. “It was on just such a bench,” Waldrop recalled, “that I heard about what was going on down at Oak Ridge, Tennessee—something about a bomb made of split atoms—for which Baruch was helping put together the labor force. He told me to keep mum and I did, but that should signify that Baruch was a very heavy carrier of important information in World War II. And he was tickled to have Inga come up to visit him, weekends, at his place on Long Island. He also carried on long palavers with her on the telephone which the FBI faithfully took down.” It’s not known whether Hoover, an expert on double standards, intervened with Baruch, as he did with Joe Kennedy.

(#ulink_20c9a7d1-3c95-5557-80c1-5aee1f0b982b)In an interview for this book in 1995, the ninety-year-old Waldrop, who first met Joe Kennedy, a fellow isolationist, in the 1930s, said that “the best way I know how to tell you how much smarter Franklin Roosevelt was than Joe Kennedy” was by citing a classic FDR story that had been relayed to him by Edward A. Tamm, a senior aide to Hoover who later became a highly respected judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Tamm began, Waldrop said, by asking whether Waldrop “knew the difference between an amateur and a pro.” Waldrop said no. Tamm then told him the following: “FDR asked Hoover to come along to the White House. Hoover brought me along. He asked Hoover to get the goods on Jim Farley,” the politically contentious postmaster general who was suspected by Roosevelt of leaking inside stories to an anti-Roosevelt newspaper columnist.

“Hoover said, ‘I won’t do it.’

“FDR outraged: ‘What!’

“Hoover: ‘I won’t do it.’

“FDR: ‘I’m ordering you to.’”

At this point, Tamm told Waldrop, Roosevelt was “quick enough to realize something was up. He asked Hoover: ‘Why not?’

“Hoover: ‘I’ll put it on the other guy’”—the reporter—rather than wiretap a member of the cabinet.

“Roosevelt almost fell down laughing,” Tamm told Waldrop, “and said, ‘Edgar, I’m not going to tell you your business anymore.’”

Waldrop’s point was that Roosevelt was tougher than Kennedy in ways Kennedy could not fathom: “Joe never understood how FDR could smile and smile and be a villain. Joe thought once he was dealing with a friend, they could make a crooked deal.”

7 NOMINATION FOR SALE (#ulink_e8985bbc-93dd-53b6-937e-f16a4713f451)

John F. Kennedy’s rise is a story that has been told and retold in hundreds of biographies and histories. The senator, always suntanned, with his photogenic wife and daughter, was the subject of articles for national magazines month after month in the late 1950s. When he wasn’t being interviewed, the senator, who relied on speechwriters on his staff and those in the pay of his father, published scores of newspaper and magazine articles as well as the bestselling Profiles in Courage, which won the 1957 Pulitzer Prize for biography.

Kennedy’s political standing was given an enormous boost at the 1956 Democratic National Convention, when he narrowly lost a dramatic floor fight against Senator Estes Kefauver for the nomination as Adlai Stevenson’s vice presidential running mate in the party’s doomed campaign against Dwight D. Eisenhower. Kennedy’s grace and seeming good humor in defeat, and his boyish good looks—viewed by millions of television watchers—overrode his lackluster record in the Senate and made him an early favorite for the party’s nomination in 1960. Kennedy ran hard over the next four years, spending most weekends making speeches and paying political dues at fund-raising dinners across America.

He made his mark not in the Senate, where his legislative output remained undistinguished, but among the voters, who responded to Kennedy as they would to a famous athlete or popular movie star. From the start the campaign was orchestrated by Joe Kennedy, who as a one-time Hollywood mogul understood that his son should run for president as a star and not as just another politician. In an exceptionally candid interview in late 1959 at Hyannis Port with the journalist Ed Plaut, then writing a preelection biography of Jack, the elder Kennedy said that his son had become “the greatest attraction in the country today. I’ll tell you how to sell more copies of your book,” Kennedy told Plaut. “Put his picture on the cover.” Plaut made a transcript of his interview available for this book.

“Why is it,” Kennedy asked, “that when his picture is on the cover of Life or Redbook that they sell a record number of copies? You advertise the fact that he will be at a dinner and you will break all records for attendance. He will draw more people to a fund-raising dinner than Cary Grant or Jimmy Stewart and anyone else you can name. Why is that? He has the greatest universal appeal. I can’t explain that. There is no answer to Jack’s appeal. He is the biggest attraction in the country today. That is why the Democratic Party is going to nominate him. The party leaders realize that to win they have to nominate him.

“The nomination is a cinch,” Joe Kennedy told the reporter. “I’m not a bit worried about the nomination.”

By the summer of 1960, with brother Bobby serving as campaign manager and father Joe as a one-man political brain trust—as well as secret paymaster—Jack Kennedy arrived at the Democratic convention in Los Angeles as an unstoppable front-runner who apparently had earned the right to be the presidential candidate by running in, and winning, Democratic primary elections across America. He had conducted a brilliant campaign that would set the standard for future generations of ambitious politicians, especially in its relentless tracking and cataloguing of delegate votes. One of Kennedy’s loyal aides, Ted Sorensen, would describe admiringly in Kennedy, his 1965 memoir, how Kennedy went over the heads of the backroom politicians and took his campaign to the people:

He had during 1960 alone traveled some 65,000 air miles in more than two dozen states—many of them in the midst of crucial primary fights, most of them with his wife—and he made some 350 speeches on every conceivable subject. He had voted, introduced bills or spoken on every current issue, without retractions or apologies. He had talked in person to state conventions, party leaders, delegates and tens of thousands of voters. He had used every spare moment on the telephone. He had made no promises he could not keep and promised no jobs to anyone.

What no outsider could imagine—and what Sorensen did not write about—was the obstacles overcome and the carefully hidden deals engineered as Kennedy achieved one political victory after another en route to Los Angeles.

Kennedy’s most important primary victory came on May 10 in West Virginia. In his campaigning in the state, Kennedy directly confronted the religious issue, telling audiences, for example, that no one cared that he was a Catholic when he was asked to fight in World War II. He defeated Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota by more than 84,000 votes. In his memoir, Sorensen quoted another of Kennedy’s unsuccessful rivals for the nomination, Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri, as saying after the convention: “He had just a little more courage, … stamina, wisdom and character than any of the rest of us.”

Sorensen’s account, as with so much of the Kennedy history as told by Kennedy insiders, has many elements of truth but is far from the whole story. The Kennedys did not depend solely on hard work and stamina to win the primary elections en route to the Democratic nomination. They spent as never before in American political history. In West Virginia, the Kennedys spent at least $2 million (nearly $11 million in today’s dollars), and possibly twice that amount—much of it in direct payoffs to state and local officials.

A far more complete account of the campaign emerges in the unpublished memoir of one of Kennedy’s most trusted, and little-known, advisers during the 1960 campaign, Hyman B. Raskin, a Chicago lawyer who had helped manage Adlai Stevenson’s presidential campaigns in 1952 and 1956. Raskin had been recruited in late 1957 by Joe Kennedy, and secretly paid, to help plan and organize his son’s drive for the presidency. Raskin, who after the 1960 election retired to his law practice, died in comfortable obscurity in 1995 at the age of eighty-six in Rancho Mirage, California. His widow, Frances, later provided for this book a copy of his memoir, entitled A Laborer in the Vineyards, which contains a rare firsthand account of Joe Kennedy’s direct, and powerful, intervention in national politics on behalf of his son—interventions that were always hidden from the press. In Raskin’s account, the combination of unlimited campaign funding, Joe Kennedy’s high-level political connections, and Jack Kennedy’s strong showing in the Democratic primaries—especially his West Virginia victory—enabled the Kennedys to fly to Los Angeles knowing they had enough ironclad delegate commitments to win on the first ballot.

At the convention site, Raskin was entrusted with the all-important task of running communications. The Kennedys, in one of their political innovations, had leased a trailer and filled it with state-of-the-art communications gear that enabled the campaign’s backroom operators to reach the leaders of state delegations instantly. In his memoir, Raskin depicted the convention as anticlimactic for the campaign insiders: “We were confident that the [delegate count] numbers which the state reports produced would closely approximate those we had before the initial [convention] meeting was held.… It appeared impossible for Kennedy to lose the nomination. The votes merely needed to be officially tabulated; therefore, in my opinion, if he failed, it would be the result of some uncontrollable event.”

Texas senator Lyndon B. Johnson’s last-minute declaration just days before the convention that he would, after all, be a candidate for the presidency—an announcement that created a flurry of press reports—was too little, too late, in Raskin’s view. “The front-runner was unbeatable,” he wrote. “For unknown reasons, some members of the press refused to concede the nomination of Kennedy, ignoring the arithmetic reported by their associates.… Johnson and his managers must have had access to the same information. Much of it was published and verifiable through Johnson connections in almost every state. Why then, I asked myself, did the anti-Kennedy forces continue their futile struggle?” Johnson stayed in the race until the presidential balloting and suffered an overwhelming defeat by Kennedy on the convention floor.

The fact that Kennedy had locked up the nomination weeks in advance of the convention was one of the campaign’s secrets. There were other secrets far more damaging, any one of which, if exposed, could cost the handsome young candidate his otherwise assured presidential nomination.

The most dangerous problem confronting the Kennedys before the convention was the hardest to fix, for it was posed by a group of reporters from the Wall Street Journal who were raising questions about the huge sums of cash that had been spent by the Kennedys to assure victory in the West Virginia primary. Their story, triggered by the instincts of an on-the-scene journalist, never made it into print.

Alan L. Otten, the Journal correspondent who covered the campaign, had been stunned by the strong Kennedy showing. He had spent weeks walking through the cities and towns of the coal counties and concluded, as he wrote for the Journal, that Humphrey would capitalize on the pronounced anti-Catholicism in West Virginia and win the Democratic primary handily. “Every miner I talked to was going to vote for Humphrey,” Otten recalled in a 1994 interview for this book. The reporter, who later became chief of the Journal’s news bureau in Washington, was suspicious when the votes were counted and urged his newspaper to undertake an extensive investigation into Kennedy vote buying. “We were fairly convinced that huge sums of money traded hands,” Otten told me.