По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

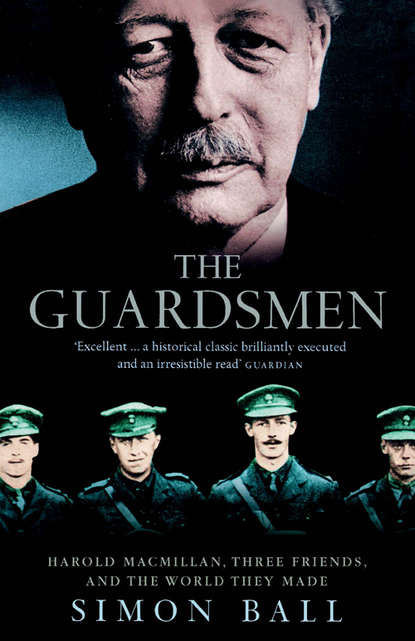

The Guardsmen: Harold Macmillan, Three Friends and the World they Made

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#litres_trial_promo) Once more his boss’s echo, Henderson, called the Turks ‘misguided barbarians’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Any hopes that Rumbold may have had of a stalemate in the Graeco-Turkish War were soon dashed. At the end of August 1922 the Kemalists opened their major offensive and routed the Greeks. By the second week in September they had captured the port of Smyrna. Not only did this pave the way to horrific ethnic cleansing, it also meant that nationalist forces directly threatened the straits zone held by the Allies. True to form, Pellé slipped out of Constantinople to negotiate directly with Kemal; on 20 September the French and Italians abandoned the British garrisoning Chanak on the Dardanelles. Three days later British and Turkish troops came into contact for the first time.

On 26 September Harington cabled Lord Cavan, now Chief of the Imperial General Staff, ‘Losing a lot of lives in hanging on is what I want to guard against. Why not start at once and give Turkey Constantinople and [Eastern Thrace]…Remember Turks are within sight of their goal and are naturally elated.’ On the same day Crookshank wrote his private appreciation of the situation: ‘We have got into a nice mess here haven’t we!’ He placed the blame for his predicament squarely on the shoulders of his senior colleagues.

I consider [Rumbold] a good deal to blame for the situation having arisen. He often I fancy sends telegrams which he thinks will please [Curzon] or [Lloyd George] rather than containing his own views. The last four or five months can be summed up as a world wide wrangle (short sighted) with France everywhere, owing to this very wicked anti-French feeling that has been brewing everywhere in the FO: as far as this part of the world is concerned it consisted in endless verbal quibbles in answering each others’ notes – if HR had any views of his own, he should have pushed them forward and gone on arguing for an immediate Conference. Instead precious months were wasted, whose bad fruit we are now beginning to taste. You can hardly believe [he concluded maliciously] what an atmosphere of gloom surrounds [Rumbold] and Henderson. My lighthearted flippancy, I can assure you, is far from appreciated.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was at this point that Crookshank had, to his delight, his first brush with high policy. He and the military attaché, Colonel Baird, ‘wrote an interesting and logical joint memorandum which was dished out with one of their meetings to Rumbold [and] the General…The General thought it wise and telegraphed the suggestions to the War Office…The suggestion was that in order to keep ourselves out of the war we should act with complete neutrality and allow the Turks to go to Thrace if they could. At present we are controlling the Marmora against them and so acting as a rearguard to the Greeks.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In London Lloyd George’s government was puffing itself up with righteous indignation to face down the Turks.

(#litres_trial_promo) When the Cabinet met at 4 p.m. on 28 September they had before them Harington’s dispatch of the Crookshank-Baird memorandum, which had arrived via the War Office. Rumbold had been too slow off the mark to register his dissent. His telegram did not reach London until 8.15 p.m. As a result the Cabinet believed that he in some way concurred with Harington. Curzon signalled a rebuke to them both. According to London the proposal

would involved [sic] consequences which Harington has not fully foreseen…The liberty accorded to Kemal could not in logic or fairness be unilateral. If he were permitted to cross into Europe to fight the Greeks and anticipate the decision of peace conference establishing his rule in Eastern Thrace, Greek ships could not be prevented from using non-neutral waters of Marmora at same time, in order to resist his passage…In this way proposed plan might have consequence of not only re-opening war between Turkey and Greece but of transferring theatre of war to Europe with consequences that cannot be foreseen.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Crookshank cared not one whit that his plan had been shot down in flames. He was simply delighted that ‘Rumbold…got his fingers smacked for not having sent his comments at once’ and that ‘little Harry…[had] caused a Cabinet discussion and a slight flutter’.

(#litres_trial_promo) In fact his memorandum was the high point of the crisis as far as Crookshank was concerned. Harington and Rumbold put aside their differences to thwart London’s desire to provoke a shooting war with the Kemalists. As Crookshank was writing up his part in the proceedings, Harington left Constantinople to open direct negotiations with the Kemalists. Early on the morning of 11 October he signed the Mudania Convention: the British, French and Italians would remove Eastern Thrace from Greek control and in return the Turks would retire fifteen kilometres from the coast at Chanak.

The Chanak crisis was an exciting time for Crookshank at its epicentre. It also had profound reverberations for British politics. Indeed, the crisis did much to create the political arena which he and Macmillan subsequently entered. The Dominions had refused to support Britain in its potential war with the Turkish nationalists. The majority of Conservative MPs became convinced that they could no longer support a coalition led by Lloyd George. On 7 October the Conservative leader, Bonar Law, publicly criticized government policy in a letter to The Times. If the French were not willing to support Britain, the government had ‘no alternative except to imitate the Government of the United States and to restrict our attention to the safeguarding of the more immediate interests of the Empire’.

(#litres_trial_promo) No one stationed in Constantinople in the autumn of 1922 could hope for a sudden collapse of the British position – Crookshank feared ‘an internal pro-Kemal and anti-foreign outbreak in [Constantinople] itself…we have very little strength to cope with that, and one day we may find ourselves like the Legation did at Peking in Boxer times…how ignominious it would be to be killed by a riotous mob, after all the battles one has been through.’ Once the immediate threat of anarchy was averted at Mudania, however, Crookshank could not have agreed with Bonar Law more: ‘I am quite convinced,’ he wrote at the beginning of November, ‘that having made a stand in October, having refused to be browbeaten and having been vindicated we should now wash our hands of the whole thing.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Chanak convinced Crookshank that politics rather than diplomacy was the career to be in. Junior diplomats did not get the opportunity to fight for great causes. One incident further finally soured him on a diplomatic career. He despised Nevile Henderson, who was left in charge of the Commission when Rumbold departed to act as Curzon’s adviser at the conference convened at Lausanne to draw up a new peace treaty with Turkey. ‘Henderson goes on, with his temper fraying more and his long-winded words in dispatches misapplied more than ever! Lately he talked about Zenophobic and also mentioned the “opaque chaos” of the country. He will not hear of corrections and I can’t help thinking the Department must laugh a bit.’ It was not so much Henderson’s bad English that he found truly offensive as the fact that he was an egregious crawler. Any ambitious man in a hierarchical structure like the Foreign Office had to try and make a good impression on his superiors. What really stuck in Crookshank’s throat was Henderson’s willingness to chum up with any potentially powerful figure, however unacceptable.

In the autumn of 1922 the Labour politician Ramsay MacDonald visited Constantinople. He did not have nice things to say about the Allies in Constantinople. ‘Away from the Galata Bridge,’ he wrote in The Nation, ‘the tunnel tramway leads up to the European quarter where the West, infected by the sensuous luxuriousness of the East, is iridescent with putrefaction, where the bookshops are piled with carnal filth, and where troops of coloured men in khaki can be seen in open daylight marching with officers at their head to where the brothels are.’

(#litres_trial_promo) MacDonald’s most famous moral stand was, however, not against pornography and prostitution but against war. He had been the most outspoken critic of the Great War from a pacifist standpoint. In February 1921 he tried to win the Woolwich by-election for the Labour party. It was a vicious campaign, his opponent being a former soldier who had won the VC at Cambrai. Placards on local trams asked, ‘A Traitor for Parliament?’ ‘The Woolwich exserviceman,’ MacDonald had retorted, ‘knows that military decorations are no indication of political wisdom, and that a Parliament of gallant officers will be a Prussian Diet not a British House of Commons.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In Constantinople Crookshank was certainly one gallant officer who agreed that MacDonald was a traitor. To Crookshank’s fury, Henderson, ‘with as always an eye on the main chance asked him to dine in the Mess which I was running at the time’. Crookshank kicked up a stink: ‘I point blank refused to be there and went out to an hotel.’ His valet, Page, a former guardsman, ‘like master like man…refused to wait at table on the “traitor”’. The spat, although minor, was hardly private: one of Crookshank’s friends heard about it while serving in the Sudan.

(#litres_trial_promo) Within two years MacDonald was prime minister, within nine years he was a prime minister at the head of the Conservative administration. Crookshank had made a dangerous enemy.

By November 1922 he was ‘fed up to the teeth’ with Constantinople ‘and everyone else and the preposterous Rumbold’.

(#litres_trial_promo) By the next summer Crookshank was ‘beginning to feel very desperate about this place’. The Turks having had their demands met by the great powers at Lausanne were cocky and unpleasant, ‘constant instances of rough handling, maltreatment etc. happen’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Even his hero Harington was beginning to irritate him: ‘The Army went off, as Harington told us about forty million times, with “flag flying high” – but the Turks let themselves go at once in scurrilous abuse. You never read such filth as they wrote. They had a final ceremony, entirely inspired by Harington – three Allied guards of honour and one Turkish and everyone saluting each others flags and then the Allies marching off leaving the Turks in situ. This resulted in a lot of stuff about “the Allies have bowed themselves before our glorious flag” and have “proved the victory of Eastern over Western Civilisation”. Ugh!’

(#litres_trial_promo) Those left when the troops marched away knew that this was not peace with honour but a bloody nose.

Crookshank believed that the British Empire should dish out punishment rather than receive it. He thus found a political hero in the South African prime minister, Jan Christian Smuts, who visited London in October 1923. Smuts charmed his hosts by heaping obloquy on the French for their arrogance, failures, unreliability and stupidity. More importantly, the former Boer leader propounded a noble vision of empire: ‘Here in a tumbling, falling world, here in a world where all the foundations are quaking,’ he declared in an address at the Savoy, ‘you have something solid and enduring. The greatest thing on earth, the greatest political [organization] of all times, it has passed through the awful blizzard and has emerged stronger than before…It is because in this Empire we sincerely believe in and practise certain fundamental principles of human government, such as peace, freedom, self-development, self-government.’ According to Smuts Irish independence, self-government in India, the end of the Protectorate in Egypt – which could all be read, like Chanak, as examples of British power buckling in the face of violent nationalism – in fact bore ‘testimony to the political faith which holds us together and will continue to hold us together while the kingdoms and empires founded on force and constraint pass away’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The sentiments were hardly original, but that they should be expressed so eloquently at that moment by a former enemy gave them huge impact. The Times reproduced the speech as a pamphlet. More immediately Smuts’s words hummed down the wires to British missions around the world. Here was a political leader and a political creed worthy of admiration. Having read Smuts with ‘daily increasing imagination’, Crookshank concluded, ‘there is a lure about politics, especially in their present Imperial aspect.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

At exactly the same time as Crookshank’s mind was turning to politics and Empire so was Harold Macmillan’s. Macmillan, like Crookshank and Cranborne, was attracted to the idea of foreign climes.

(#litres_trial_promo) Macmillan’s contacts were perhaps not as highly placed as Cranborne’s, but he was not without resources. His first port of call was George Lloyd, a former Conservative MP whom he had met through his Oxford Union activities. Lloyd was about to depart for India as Governor of Bombay and offered Macmillan a post as his ADC. It was not to be, since the Bombay climate was, as his doctors pointed out, hardly ideal for a man with still suppurating wounds. Macmillan wanted to be an ADC, however, and an imperial governor operating in a colder climate was desperate for his services.

Victor Cavendish, ninth Duke of Devonshire, had been shipped off to Canada for the duration in 1916. At times he felt himself sadly neglected – not least in the matter of ADCs. The kind of young men His Grace wanted were not to be had when there was a war on. Those he was sent were ‘worse than useless’.

(#litres_trial_promo) They were as keen to leave him as he was to be rid of them.

(#litres_trial_promo) His wife, Evie, was dispatched to London on a desperate mission to recruit some new blood. Although Macmillan was not one of the young aristocrats Devonshire had in mind, Nellie Macmillan was an acquaintance of the Duchess of Devonshire from the pre-war charity circuit. Harold was laid in her path and snapped up with gratitude. When he stepped off the boat in Canada, he was greeted by a most eager employer. The bond was sealed by a game of golf. ‘He plays quite well and is much better than I am,’ noted Devonshire, for whom his own lack of prowess on the links was a constant lament. ‘Macmillan is certainly a great acquisition,’ the duke concluded.

On departing for Canada, Macmillan had planned to take a close interest in the North American political scene. The main interest of the Devonshire circle, as it turned out, was romance. The two Cavendish girls had been deprived of suitable male company for nearly three years and were more than a little excited by the arrival of so many eligible young bachelors. Lady Rachel Cavendish whisked the new ADCs straight off the boat to a dance. Within a month of their arrival Macmillan’s fellow ADC, Harry Cator, ‘a most attractive boy’, had to be disentangled from an unsuitable romantic attachment.

(#litres_trial_promo) Unlike his friend, Macmillan was no young blade, but within months he had shown an interest in the Devonshires’ other daughter, Lady Dorothy. At the end of July the duke noticed that they had ‘got up early to go to M’ Jacques to see the sun rise’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Devonshire regarded Macmillan as a perfectly acceptable match for his daughter.

(#litres_trial_promo) Lady Dorothy herself seemed much less sure. ‘After tea,’ one day at the beginning of December 1919, ‘Harold proposed in a sort of way to Dorothy but although she did not refuse him definitely nothing was settled. She seemed to like him but not enough to accept and says she does not want to marry just yet.’ Her father was glad to see that ‘She seemed in excellent spirits. After dinner they went skating.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Macmillan broke her down over Christmas. On Boxing Day 1919 ‘Dorothy and Harold settled to call themselves engaged’.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘I do hope it is alright,’ noted her father worriedly.

(#litres_trial_promo) There was certainly something in the air that Canadian New Year which inclined the young to romance: two more of Harold’s fellow ADCs also became engaged.

When Harold Macmillan married Dorothy Cavendish in April 1920 at St Margaret’s, Westminster – the same church Oliver and Moira Lyttelton had used a few weeks previously – he committed himself to making money from publishing. At the same time he gained an entree into high politics. Devonshire was very fond of his new son-in-law. Indeed, he saw something of his young self in him. He himself had been an enthusiastic professional politician, a ‘painstaking’ financial secretary to the Treasury. In many ways his elevation to a great dukedom – which he inherited from his uncle – had deprived him of a career.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Devonshire gladly re-entered politics in October 1922 when the coalition disintegrated over Chanak. Victor Devonshire replaced Winston Churchill in the Cabinet as colonial secretary. While in Canada, Devonshire ‘found’, as Macmillan recalled, ‘that I was interested in political problems, he would discuss them freely with me’.

(#litres_trial_promo) In London this habit continued – but now with much more interesting issues to mull over.

(#litres_trial_promo) Macmillan remembered calling on the duke during the course of the formation of Bonar Law’s government. ‘I found Lord Derby in conference with him. The Duke…pointed out the extreme weakness of the front bench in the House of Commons…“Ah,” said Lord Derby, “you are too pessimistic. They have found a wonderful little man. One of those attorney fellows, you know. He will do all the work.” “What’s his name?” said the Duke. “Pig,” said Lord Derby. Turning to me, the Duke replied, “Do you know Pig?”…It turned out to be Sir Douglas Hogg!’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The most pressing policy issue that Victor Devonshire had to face at the Colonial Office was the need for some kind of new relationship with two British colonies in Africa: Rhodesia and Kenya. Both were examples of entrepreneurial colonies – initially exploited by chartered companies. Each had a group of European settlers keen to lay their hands on as much political power as possible. Yet in Kenya and Rhodesia the white settlers were only a small proportion of the total population, the majority being made up of indigenous Africans. The dream of Commonwealth came directly into collision with the duties of trusteeship. The Colonial Office’s official view was that ‘whether therefore we look to natives for whom we hold a trusteeship or [a] white community which is insufficiently strong politically and financially – the obstacles to early responsible government…appear prohibitive’. In each case the solution in the eyes of civil servants in London was to incorporate these small but troublesome outposts of empire into some wider whole. In the case of Rhodesia, union with South Africa seemed to beckon; in the case of Kenya, closer association across the Indian Ocean with India. Whitehall had, however, underestimated the contrary spirit of the settlers. In both countries the settlers spawned rebarbative political leaders quite willing to defy the mother country.

In Southern Rhodesia the opposition was led by Sir Charles Coghlan, an Irish Roman Catholic lawyer from Bulawayo. In London Smuts might be hailed as the great imperial statesman-visionary. In Salisbury he was seen as little more than the frontman for Boer imperialism. When he declared that ‘the Union is going to be for the African continent what the United States has become for the American continent; Rhodesia is but another day’s march on the high road of destiny’, Rhodesian unionists took it as a signal that a republican South Africa might secede from the Empire. In November 1922 the settlers voted by 59.43 per cent to 40.57 per cent against union with South Africa.

(#litres_trial_promo) Effectively they forced the British government to buy out the chartered South Africa Company and grant self-government. The negotiations created much ill-will. In July 1923 the Colonial Office gave the company two weeks to accept appropriation. Devonshire’s under-secretary, Cranborne’s brother-in-law and friend, Billy Ormsby-Gore, struck a deal that gave the company three and three-quarter million pounds and half the proceeds on government land sales until 1965.

(#litres_trial_promo) The deal left a settler community confident in its own power to manipulate Britain and a disgruntled company that, all admitted, still dominated the economic life of its former domain.