По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

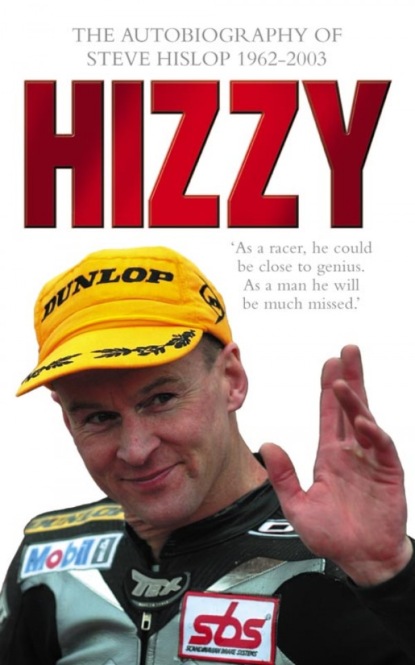

Hizzy: The Autobiography of Steve Hislop

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Hizzy: The Autobiography of Steve Hislop

Steve Hislop

Steve Hislop was one of the most famous motorcycle racers in the world. He had always been a controversial and outspoken character having had many famous clashes and splits with teams and riders over the years, not always to his advantage. Season 2003 was no different. Steve’s life was incredible, funny and ultimately tragic.Hislop made his debut in 1979 on a bike paid for by his father, but when the latter died of a heart-attack, he embarked on a self-destructive quest that resulted in more crashed bikes and cars than he can remember. Three years later his brother Garry was killed racing at Silloth.It looked as if he would never race again but while on holiday at the Isle of Man TT races in 1983, he was mesmerised by the sight of Joey Dunlop and he knew he had to try it.He took to the roads immediately, amassing an amazing career record of 11 wins and was the first rider in history to lap the course at an average speed of over 120mph. Hizzy's TT victories over big name rivals like Joey Dunlop and Carl Fogarty made him a living legend beyond the confines of just the UK. He turned his back on the Isle of Man in 1994, claiming it was too fast and dangerous for modern superbikes.However, he had already proved he was just as fast on purpose-built short circuits having won the British 250cc championship in 1990 and then went on to win the British Superbike (BSB) title in 1995 and 2002.Defending a title is always difficult and made even harder when your current team doesn't give you a new contract. However, season 2003 started positively for Steve, inasmuch as he found a new team, but he was sacked half way through the season after a string of poor results on an uncompetitive bike. These events, however, paled into insignificance when Steve was killed in July 2003 when the helicopter he was flying crashed in a remote Scottish border region. His book is a fitting tribute to a motor racing legend.

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF

STEVE HISLOP 1962–2003

HIZZY

with STUART BARKER

Dedication (#ulink_e437f627-d8e3-564f-aebd-99a1c62bdccd)

For Aaron and Connor Hislop – sons of a very special dad

Contents

Cover (#u453df8ed-d854-50cb-8845-572b8918733a)

Title Page (#u77e936fe-f6ab-5766-88d6-60984c0b554a)

Dedication (#u0c82e84c-3e37-5341-9f5d-d3ba020db215)

1 Day Number One, Life Number Two (#u607ec2f1-2c86-51df-8fdd-4caebb274d8a)

2 Shooting Crows (#u1ac27c31-f0d8-5f24-a9d5-7bacb754e920)

3 Off the Rails (#uc494f7be-6df7-508c-bc78-58c4018be944)

4 Tales from the Riverbank (#u83e26ed0-b260-54d8-bd68-fa1402de63f6)

5 The Flying Haggis (#u3c2a49f1-2dc8-5ab7-89e0-6e4dfbb132db)

6 The Burger Van Queue (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Money, Money, Money (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Girls, Girls, Girls (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Bored (#litres_trial_promo)

10 The Impossible Dream (#litres_trial_promo)

11 A Day at the Races (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Champ (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Sacked (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Sacked Again (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Swearing at Fairies (#litres_trial_promo)

16 2002: A Race Odyssey (#litres_trial_promo)

17 The Final Lap (#litres_trial_promo)

18 A Scottish Hero (#litres_trial_promo)

Career Results (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 Day Number One, Life Number Two (#ulink_cad97eff-feb4-5511-b345-af2562eb2bf6)

‘I’d been trying to race bikes for a month with a broken neck.’

Everyone thought I was dead – except me because I wasn’t thinking at all.

I lay unconscious in the gravel trap at Brands Hatch with my neck broken in two places, my spinal cord twisted into an ‘S’ shape and with a fragment of bone impregnated in the main nerve to my left arm. It was one of the most horrendous-looking crashes anyone had ever witnessed – and there were more than 100,000 people at the race that day. Even the national newspapers hailed it as the worst crash ever seen on TV.

World Superbike riders Neil Hodgson, Colin Edwards and Noriyuki Haga all got tangled up at about 120mph going into the fearsome Paddock Hill bend at Brands Hatch during the year 2000 WSB meeting. Neil had clipped the kerb because he couldn’t see where he was going as all the other riders were so tightly bunched. His bike bounced back onto the track and started a chain reaction and I got caught up in the mêlée as Haga rammed my back wheel and Edwards took my front wheel away. The result was total carnage: there were bikes and riders tumbling everywhere, bits and pieces flying off the machinery and scything through the air and sparks showering down the track as metal collided with tarmac.

As my bike was rammed, I was thrown 15 feet in the air and started cartwheeling towards the gravel trap. My bike was spinning end over end and it slammed into my head twice – all 350lb of it – sending me tumbling even more spectacularly. It’s a good job it did too because, ironically, that’s probably what saved my life. The first smack it gave me knocked me out so I was unconscious as I tumbled and that meant my body was limp and relaxed. Had I been conscious and tensed up, I would probably have done even more damage to myself.

After doing four full-body cartwheels, I landed square on the top of my head with my feet pointing straight up in the air, as if I’d been planted in the ground by the celebrity gardener, Alan Titchmarsh. Then finally I tumbled over, came to a halt and slumped into the gravel, knocked out cold and lifeless as the dust began to settle and the bike finally came to a stop. The race was stopped immediately and the huge crowd that had been screaming and cheering just seconds before then, fell completely silent. Joey Dunlop had been killed in a race just one month previously and no one wanted to witness more tragedy at what should have been a fun day out. I don’t know what the millions of armchair fans watching on TV around the world thought but what did annoy me afterwards was that it took such a horrific crash to get bike racing onto the main news. Usually the sport is never considered important enough to be mentioned on TV news bulletins unlike football, cricket, golf, Formula One or tennis. It was only when I had such a horrendous smash that almost every country in the world ran a story on it. What a way to get famous.

But if it weren’t for the TV coverage, I wouldn’t be able to describe the crash in detail because I can’t remember it. The last thing I remember was feeling a thump when I was banking hard into Paddock Hill bend and that must have been when Haga hit me. Because the crash looked so bad and because I had landed on my head and wasn’t moving, everyone who witnessed it presumed I was dead. My girlfriend Kelly, who was watching on TV back home, was in hysterics and couldn’t get through to anyone in my team when she tried to call to find out if I was alive or dead. The Virgin Yamaha team wasn’t taking calls because they were too busy trying to find out if they still had a rider. Kelly had to wait for about two hours before she got through to someone who told her I was OK. At first she didn’t believe it and thought I must at least be in a coma, but someone finally convinced her that I was conscious and moving.

The first thing I remember through a foggy, dizzy haze was hearing a paramedic’s voice shouting, ‘there’s a good vein, stick it in there,’ as they immediately tried to stabilize me by hooking me up to an IV drip and an oxygen mask. Apart from that, everything was completely silent as the crowd looked on numbed and fearing the worst. There were paramedics swarming all over me and thankfully they knew to remove my helmet carefully with the aid of a neck brace because there was a risk of spinal injuries.

As I was stretchered off to the nearest hospital I started coming round a little and that’s when I felt a pain in my chest and thought I might have broken my back. I was also getting a prickly feeling every time a medic touched me but it turned out that I was just covered in thousands of scratches from the gravel as I tumbled through it.

Anyone who thinks motorcycle racing is glamorous only needs to experience one big crash to realize it’s not. The frequent injuries are bad enough to deal with but the undignified hospital procedures are just as bad. On this occasion, I was still feeling groggy when a doctor wearing rubber gloves approached me and that can mean only one thing. Sure enough, I jolted as he inserted a finger straight up my backside and had a prod around but at least he was kind enough to explain the theory he was putting into practice. Apparently, men have a kind of ultra-sensitive G-spot up there and if you hit the ceiling when the doctor touches it, you’ve got a broken back. I’d have thought most blokes would hit the ceiling anyway when a doctor shoves a finger up their arse, broken back or not but apparently I didn’t flinch too violently so the prognosis was good even if the examination wasn’t.

I was then x-rayed and pushed into a little cubicle and left on my own for what seemed like an eternity as I still hadn’t a clue what was happening to me. Coming round from concussion is not a nice experience and even though I’d been knocked out several times before, it doesn’t get any easier because you’re starting from scratch every time it happens as you’ve got no memories to draw upon.

I was really scared lying in there trying to piece my world together bit by bit. Where am I? What day is it? What year is it? The answer to every question was the same – I didn’t know. I could only lie there like a newborn baby staring at the curtains round my bed, my brain completely devoid of any memory, any sense of belonging or any history; any sense of anything in fact. It really was like being born again – I didn’t have a bloody clue what was going on.

Eventually, with a huge effort, I remembered I’d been at Brands Hatch but I still couldn’t remember what year it was. I became convinced it was 1999 and only realized it was the year 2000 because I remembered which front suspension system I’d been using on the bike and that I’d been swapping between 1999 and 2000-spec forks that season. It’s the most horrible, helpless feeling there is but for bike racers, it comes with the territory and you’ve just got to get on with it.

Some time later, my team boss, Rob McElnea, came in to see me and started asking me questions. As a former racer himself, he knew the routine for concussion as well as anyone and when I could tell him who I was, where I was and what year it was he reckoned I was all right and tried to get me to sign myself out.

Steve Hislop

Steve Hislop was one of the most famous motorcycle racers in the world. He had always been a controversial and outspoken character having had many famous clashes and splits with teams and riders over the years, not always to his advantage. Season 2003 was no different. Steve’s life was incredible, funny and ultimately tragic.Hislop made his debut in 1979 on a bike paid for by his father, but when the latter died of a heart-attack, he embarked on a self-destructive quest that resulted in more crashed bikes and cars than he can remember. Three years later his brother Garry was killed racing at Silloth.It looked as if he would never race again but while on holiday at the Isle of Man TT races in 1983, he was mesmerised by the sight of Joey Dunlop and he knew he had to try it.He took to the roads immediately, amassing an amazing career record of 11 wins and was the first rider in history to lap the course at an average speed of over 120mph. Hizzy's TT victories over big name rivals like Joey Dunlop and Carl Fogarty made him a living legend beyond the confines of just the UK. He turned his back on the Isle of Man in 1994, claiming it was too fast and dangerous for modern superbikes.However, he had already proved he was just as fast on purpose-built short circuits having won the British 250cc championship in 1990 and then went on to win the British Superbike (BSB) title in 1995 and 2002.Defending a title is always difficult and made even harder when your current team doesn't give you a new contract. However, season 2003 started positively for Steve, inasmuch as he found a new team, but he was sacked half way through the season after a string of poor results on an uncompetitive bike. These events, however, paled into insignificance when Steve was killed in July 2003 when the helicopter he was flying crashed in a remote Scottish border region. His book is a fitting tribute to a motor racing legend.

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF

STEVE HISLOP 1962–2003

HIZZY

with STUART BARKER

Dedication (#ulink_e437f627-d8e3-564f-aebd-99a1c62bdccd)

For Aaron and Connor Hislop – sons of a very special dad

Contents

Cover (#u453df8ed-d854-50cb-8845-572b8918733a)

Title Page (#u77e936fe-f6ab-5766-88d6-60984c0b554a)

Dedication (#u0c82e84c-3e37-5341-9f5d-d3ba020db215)

1 Day Number One, Life Number Two (#u607ec2f1-2c86-51df-8fdd-4caebb274d8a)

2 Shooting Crows (#u1ac27c31-f0d8-5f24-a9d5-7bacb754e920)

3 Off the Rails (#uc494f7be-6df7-508c-bc78-58c4018be944)

4 Tales from the Riverbank (#u83e26ed0-b260-54d8-bd68-fa1402de63f6)

5 The Flying Haggis (#u3c2a49f1-2dc8-5ab7-89e0-6e4dfbb132db)

6 The Burger Van Queue (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Money, Money, Money (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Girls, Girls, Girls (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Bored (#litres_trial_promo)

10 The Impossible Dream (#litres_trial_promo)

11 A Day at the Races (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Champ (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Sacked (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Sacked Again (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Swearing at Fairies (#litres_trial_promo)

16 2002: A Race Odyssey (#litres_trial_promo)

17 The Final Lap (#litres_trial_promo)

18 A Scottish Hero (#litres_trial_promo)

Career Results (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 Day Number One, Life Number Two (#ulink_cad97eff-feb4-5511-b345-af2562eb2bf6)

‘I’d been trying to race bikes for a month with a broken neck.’

Everyone thought I was dead – except me because I wasn’t thinking at all.

I lay unconscious in the gravel trap at Brands Hatch with my neck broken in two places, my spinal cord twisted into an ‘S’ shape and with a fragment of bone impregnated in the main nerve to my left arm. It was one of the most horrendous-looking crashes anyone had ever witnessed – and there were more than 100,000 people at the race that day. Even the national newspapers hailed it as the worst crash ever seen on TV.

World Superbike riders Neil Hodgson, Colin Edwards and Noriyuki Haga all got tangled up at about 120mph going into the fearsome Paddock Hill bend at Brands Hatch during the year 2000 WSB meeting. Neil had clipped the kerb because he couldn’t see where he was going as all the other riders were so tightly bunched. His bike bounced back onto the track and started a chain reaction and I got caught up in the mêlée as Haga rammed my back wheel and Edwards took my front wheel away. The result was total carnage: there were bikes and riders tumbling everywhere, bits and pieces flying off the machinery and scything through the air and sparks showering down the track as metal collided with tarmac.

As my bike was rammed, I was thrown 15 feet in the air and started cartwheeling towards the gravel trap. My bike was spinning end over end and it slammed into my head twice – all 350lb of it – sending me tumbling even more spectacularly. It’s a good job it did too because, ironically, that’s probably what saved my life. The first smack it gave me knocked me out so I was unconscious as I tumbled and that meant my body was limp and relaxed. Had I been conscious and tensed up, I would probably have done even more damage to myself.

After doing four full-body cartwheels, I landed square on the top of my head with my feet pointing straight up in the air, as if I’d been planted in the ground by the celebrity gardener, Alan Titchmarsh. Then finally I tumbled over, came to a halt and slumped into the gravel, knocked out cold and lifeless as the dust began to settle and the bike finally came to a stop. The race was stopped immediately and the huge crowd that had been screaming and cheering just seconds before then, fell completely silent. Joey Dunlop had been killed in a race just one month previously and no one wanted to witness more tragedy at what should have been a fun day out. I don’t know what the millions of armchair fans watching on TV around the world thought but what did annoy me afterwards was that it took such a horrific crash to get bike racing onto the main news. Usually the sport is never considered important enough to be mentioned on TV news bulletins unlike football, cricket, golf, Formula One or tennis. It was only when I had such a horrendous smash that almost every country in the world ran a story on it. What a way to get famous.

But if it weren’t for the TV coverage, I wouldn’t be able to describe the crash in detail because I can’t remember it. The last thing I remember was feeling a thump when I was banking hard into Paddock Hill bend and that must have been when Haga hit me. Because the crash looked so bad and because I had landed on my head and wasn’t moving, everyone who witnessed it presumed I was dead. My girlfriend Kelly, who was watching on TV back home, was in hysterics and couldn’t get through to anyone in my team when she tried to call to find out if I was alive or dead. The Virgin Yamaha team wasn’t taking calls because they were too busy trying to find out if they still had a rider. Kelly had to wait for about two hours before she got through to someone who told her I was OK. At first she didn’t believe it and thought I must at least be in a coma, but someone finally convinced her that I was conscious and moving.

The first thing I remember through a foggy, dizzy haze was hearing a paramedic’s voice shouting, ‘there’s a good vein, stick it in there,’ as they immediately tried to stabilize me by hooking me up to an IV drip and an oxygen mask. Apart from that, everything was completely silent as the crowd looked on numbed and fearing the worst. There were paramedics swarming all over me and thankfully they knew to remove my helmet carefully with the aid of a neck brace because there was a risk of spinal injuries.

As I was stretchered off to the nearest hospital I started coming round a little and that’s when I felt a pain in my chest and thought I might have broken my back. I was also getting a prickly feeling every time a medic touched me but it turned out that I was just covered in thousands of scratches from the gravel as I tumbled through it.

Anyone who thinks motorcycle racing is glamorous only needs to experience one big crash to realize it’s not. The frequent injuries are bad enough to deal with but the undignified hospital procedures are just as bad. On this occasion, I was still feeling groggy when a doctor wearing rubber gloves approached me and that can mean only one thing. Sure enough, I jolted as he inserted a finger straight up my backside and had a prod around but at least he was kind enough to explain the theory he was putting into practice. Apparently, men have a kind of ultra-sensitive G-spot up there and if you hit the ceiling when the doctor touches it, you’ve got a broken back. I’d have thought most blokes would hit the ceiling anyway when a doctor shoves a finger up their arse, broken back or not but apparently I didn’t flinch too violently so the prognosis was good even if the examination wasn’t.

I was then x-rayed and pushed into a little cubicle and left on my own for what seemed like an eternity as I still hadn’t a clue what was happening to me. Coming round from concussion is not a nice experience and even though I’d been knocked out several times before, it doesn’t get any easier because you’re starting from scratch every time it happens as you’ve got no memories to draw upon.

I was really scared lying in there trying to piece my world together bit by bit. Where am I? What day is it? What year is it? The answer to every question was the same – I didn’t know. I could only lie there like a newborn baby staring at the curtains round my bed, my brain completely devoid of any memory, any sense of belonging or any history; any sense of anything in fact. It really was like being born again – I didn’t have a bloody clue what was going on.

Eventually, with a huge effort, I remembered I’d been at Brands Hatch but I still couldn’t remember what year it was. I became convinced it was 1999 and only realized it was the year 2000 because I remembered which front suspension system I’d been using on the bike and that I’d been swapping between 1999 and 2000-spec forks that season. It’s the most horrible, helpless feeling there is but for bike racers, it comes with the territory and you’ve just got to get on with it.

Some time later, my team boss, Rob McElnea, came in to see me and started asking me questions. As a former racer himself, he knew the routine for concussion as well as anyone and when I could tell him who I was, where I was and what year it was he reckoned I was all right and tried to get me to sign myself out.