По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

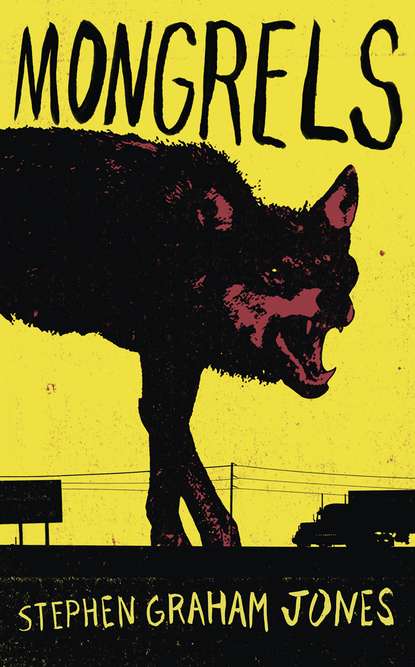

Mongrels

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He scruffed my hair, walked deeper into the house, for pants.

I peeled up the mouth of the bag, looked in.

It was all loose cash and strawberry wine coolers.

The last story Grandpa told me, it was about the dent in his shin.

Libby leaned back from the kitchen sink when she heard him starting in on it.

She was holding a big raw steak from the store to her face. It was because of Red, because of last night.

When she’d come in to get ready for work, she’d seen Darren’s trash bag on the table, hauled it up without even looking inside. She strode right back to Darren’s old bedroom. He was asleep on top of the covers, in his pants.

She threw the bag down onto him hard enough that two of the wine-cooler bottles broke, spilled down onto his back.

He came up spinning and spitting, his mouth open, teeth bared.

And then he saw his sister’s face. Her eye.

“I’m going to fucking kill him this time,” he said, stepping off the bed, his hands opening and closing where they hung by his legs, but Libby was already there, pushing him hard in the chest, her feet set.

When the screaming and the throwing things started, one of them slammed the door shut so I wouldn’t have to see.

In the living room, Grandpa was coughing.

I went to him, propped him back up in his chair, and, because Libby had said it would work, I asked him to tell me about the scar by his mouth, about how he got it.

His head when he finally looked up to me was loose on his neck, and his good eye was going cloudy.

“Grandpa, Grandpa,” I said, shaking him.

My whole life I’d known him. He’d acted out a hundred werewolf stories for me there in the living room, had once even broke the coffee table when an evil Clydesdale horse reared up in front of him and he had to fall back, his eyes twice as wide as any eyes I’d ever seen.

In the back of the house something glass broke, something wood splintered, and there was a scream so loud I couldn’t even tell if it was from Darren or Libby, or if it was even human.

“They love each other too much,” Grandpa said. “Libby and her—and that—”

“Red,” I said, trying to make it turn down at the end like when Darren said it.

“Red,” Grandpa said back, like he’d been going to get there himself.

He thought it was Red and Libby back there. He didn’t know what month it was anymore.

“He’s not a bad wolf either,” he went on, shaking his head side to side. “That’s the thing. But a good wolf isn’t always a good man. Remember that.”

It made me wonder about the other way around, if a good man meant a bad wolf. And if that was better or worse.

“She doesn’t know it,” Grandpa said, “but she looks like her mother.”

“Tell me,” I said.

For once he did, or started to. But his descriptions of Grandma kept wandering away from her, would strand him talking about how her hands looked around a cigarette when she had to turn away from the wind. How some of her hair was always falling down by her face. A freckle on the top of her left collarbone.

Soon I realized Darren and Libby were there, listening.

It was my grandma, but it was their mom. The one they’d never seen. The one there weren’t any pictures of.

Grandpa smiled for the audience, for his family being there, I think, and he went on about her pot roasts then, about how he would steal carrots and potatoes for her all over Logan County, carry them home in his mouth, shotguns always firing into the air behind him, the sky forever full of lead, always raining pellets so that when he shook on the porch after getting home, it sounded like a hailstorm.

Libby cracked the refrigerator open, pulled out a steak, held it under the water in the sink so it wouldn’t stick to her face.

Darren eased into the living room, sat on his haunches on the floor past the chair he usually claimed, like he didn’t want to break this spell, and Grandpa went on about Grandma, about the first time he saw her. She was in a parade right over in Boonesville, had a pale yellow umbrella over her shoulder. It didn’t look like a huge daisy, he said. Just an umbrella, but in the clear daytime.

Darren smiled.

His face on the left side had four deep scratches in it now, but he didn’t care. He was like Grandpa, was going to have a thousand stories.

In the kitchen Libby finally turned the water off, pressed the steak up to her left eye. It wasn’t swelled all the way shut yet. Her eyeball was shot red like it had popped.

I hated Red at least as much as Darren did.

“Go on,” Darren said to Grandpa, and for two or three more minutes we went around and around the house with him, after Grandma. Until Grandpa leaned forward to pull up the right leg of his pants. Except he was just wearing boxers. But his fingers still worked at the memory of pants.

“He wanted to hear about how this happened,” he said, and tapped his finger into a deep dent on his shin I’d never noticed before.

This was when Libby pushed up from the sink.

Her lips were red now too, and part of me registered that it was from the steak. That she’d been chewing on it.

The rest of me was watching Grandpa’s index finger tap into his shin. Because I’d asked about the scar by his mouth, not one on his leg. But I wasn’t going to mess this up.

“Used to have this dog …” he said to me, just to me, and Libby dropped her steak splat onto the linoleum.

“Dad,” she said, but Darren held his hand up hard to her. “He can’t, not this—” she said, her voice getting shrieky, but Darren nodded yes, he could.

“You weren’t there,” she said to him, and when Darren looked over to her again she spun away with a grunt, crashed out the screen door, and I guess she just kept running out into the trees. The El Camino didn’t fire up, anyway.

“What happened?” I said to Grandpa.

“We had this dog,” Grandpa said, nodding like it was all coming back to him now, moving his fingers up by his eyes like the story was filaments in the air, and if he held his hand just right he could collect enough of them to make sense, “we had this dog and he—he got tangled up with something, got bit, got bit and I had to, well.”

“Rabies,” I filled in. I knew it from the kid in class who’d had to get the shots in his stomach.

“I didn’t want to wake your sister,” Grandpa said across to Darren. “So I—so I used a ball-peen hammer instead, right? A hammer’s quiet enough. A hammer’ll work. I dragged her out by the fence on that side, and—” He was laughing now, his wheezy old man’s laugh, and fighting to stand, to act this out.

“Her?” I said, but he was already acting it out, was already holding that big rangy dog by the collar, and swiping down at it with the hammer, the dog spinning him around, his swings missing, one of them finally cracking deep into his own shin so he had to hop on one leg, the dog still pulling, trying to live.

He was laughing, or trying to.