По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

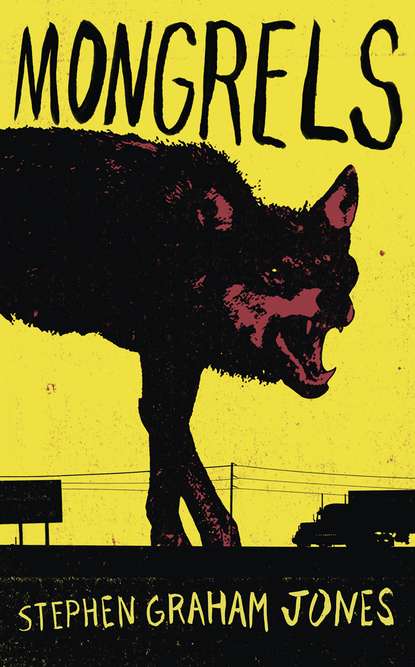

Mongrels

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Darren was leaning his head back, like trying to balance his eyes back in.

“I like, I like to—” Grandpa said, finding his chair again, collapsing into it, “once I hit her that first time, little pup, I like to have never got that next lick in,” which was the punch line.

He was the only one laughing, though.

And it wasn’t really laughing.

The next Monday Libby took me back to first grade, sat there at the curb until I’d stepped through the front doors.

It lasted two days.

When we came back from school and work Tuesday, Grandpa was half out the front door, his cloudy eyes open, flies and wasps buzzing in and out of his mouth.

“Don’t—” Libby said, trying to snag my shirt, keep me in the El Camino.

I was too fast. I was running across the caliche. My face was already so hot.

And then I stopped, had to step back.

Grandpa wasn’t just half in and half out of the door from the kitchen. He was also halfway between man and wolf.

From the waist up, for the part that had made it through the door, he was the same. But his legs, still on the kitchen linoleum, they were straggle-haired and shaped wrong, muscled different. The feet had stretched out twice as long, until the heel became the backward knee of a dog. The thigh was bulging forward.

He really was what he’d always said.

I didn’t know how to hold my face.

“He was going for the trees,” Libby said, looking there.

I did too.

When Darren walked up from wherever he’d been, he was still buttoning his shirt. It was so it wouldn’t be sweaty when he got wherever he was going, he’d told me.

I’d believed him too.

Used to, I believed everything.

He stopped when he saw us sitting on the El Camino’s tailgate.

We were splitting the lunch I hadn’t eaten at school, since the teacher had sneaked me some pepperoni slices from a plastic baggie.

“No,” Darren said, lifting his face to the wind. It wasn’t for my half of the bologna sandwich. It was for Grandpa. “No, no no no!” he screamed now, because he was like me, he could insist, he could make it true if he was loud enough, if he meant it all the way.

Instead of coming any closer, he turned, his shirt floating to the ground behind him.

I stepped down to go after him but Libby had me by the shoulder.

Because we couldn’t go inside—Grandpa was in the doorway—we sat in the bed of the El Camino, Libby’s fingernails picking at the edge of the white stripes that came up the tailgate. There was faded black underneath them, like the rest of the car. When night cooled the air down we retreated to the cab, rolled the windows up so that soon we were breathing in the taste of Red’s cigarettes. I pushed the pad of my index finger into a burn on the dashboard, then traced a crack in the windshield until it cut me.

I was asleep by the time the ground shook underneath us.

I sat up, looked through the rear window. The trees were glowing.

Libby pulled my head close to her.

It was Darren. He’d stolen a front-end loader.

“Your uncle,” Libby said, and we stepped out.

Darren pulled the front-end loader right up to the house, lowered the bucket to the doorway, and then he swung down, stepped around, lifted Grandpa into the bucket, Grandpa’s mouth hanging open, his legs shaped more like they had been. His mouth was still trying to push forward, though. Into a muzzle.

“He was too old to shift,” Libby said to me, shaking her head at the tragedy of it all.

“But what if he’d made it?” I said.

“You’re not going to be stupid too, are you?” she said, and the way she tried to smile I knew I didn’t have to answer.

Darren couldn’t call to us because the front-end loader was too loud, but he stood on the first step, hung out from the grab bar, waved us over.

“I don’t want to,” Libby said to me.

“I don’t want to either,” I said.

We climbed up with Darren, sat on the swells to either side of his bouncy, ripped-up seat, the glass cold on my left arm.

Darren drove right out into the field and followed it until there was only trees, and then he pushed through the trees back to a creek. He lifted Grandpa out, cradled him down to the tall dry grass, and then he used the bucket to dig out the steep side of the bank.

He picked his dad up in his arms, looked across to Libby, then to me.

“Your grandpa,” he said, holding him right there. “One thing I can say about his old ass. He always liked to run his dinner down instead of getting it at the store, didn’t he?”

He was kind of crying when he said it, so I looked away.

Libby bit her lip, pulled at the hair on the right side of her face. Darren lowered Grandpa into the new hole, and then he used the front-end loader to drag all the dirt back down over him, and he piled more on, finally even digging up the creek and dripping that silt down, then crushing that mound down harder and deeper and madder and madder, breaking all Grandpa’s bones, so it wouldn’t matter if anyone dug them up.

This is the way it is with werewolves.

“What about me?” I said on the way back, in the cab of the front-end loader.

“What do you mean what about you?” Darren said, and when I looked over the moon had just broke over the top of the trees, was bright and round. It outlined him perfect, the way he leaned over that steering wheel like he’d been born to it.

Every boy who never had a dad, he comes to worship his uncle.

“He means what about him,” Libby said, angling her words at Darren in a different way.

“Oh, oh,” Darren said, throttling up now that we were out of the trees. “Your mom, she—”

“Not all kids born to a werewolf are a werewolf,” Libby said. “Your mom, she didn’t catch it from your grandpa.”