По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

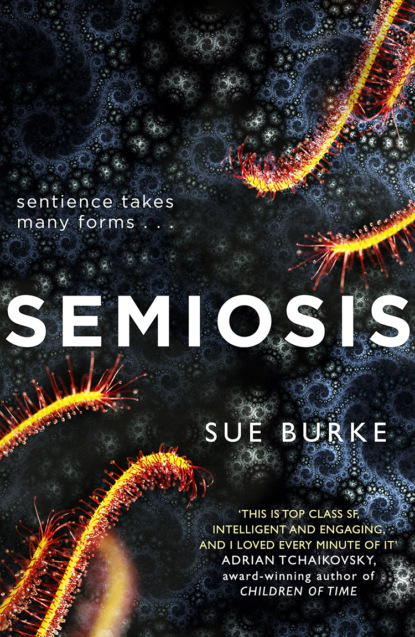

Semiosis: A novel of first contact

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Just outside the walls I found an old grove of bamboo growing around stones with painted ceramic portrait tiles, a cemetery. Digging beneath a stone, I found bones as brown as the soil. They cracked and crumbled as I tried to pull them out but I got several good pieces. I put the soil back and pried the portrait tile from the stone. I’d bring a glass maker back to the village.

We’d learned a lot, including one more thing. The bamboo was very friendly. Fruit appeared right away near the house where we stayed. Then one of the trunks where we’d tied our hammocks grew a shoot. Each of the new leaves had stripes of a different color, a little rainbow built out of leaves instead of bark to show that it had observed us and recognized us as an intelligent species like itself. It had delivered a message, a welcome home, because it wanted us to stay.

But I didn’t say that back in the village. Octavo wouldn’t want to know that this bamboo was as smart as he’d thought it was.

“This is a glass maker,” I said in the dim cellar back in the village as the storm rumbled and splashed outside. I pulled the cemetery tile from my bag.

It showed someone with four spindly legs that supported a body with an overhanging rump. Oddly bent twiggy arms and a clublike head with yellow-brown skin rose from the shoulders. The head had large gray eyes on its sides and a vertical mouth. I’d seen plenty of other pictures and figured out the anatomy. The tile was the best small picture of a glass maker I’d found. There was writing at the feet, five linear marks and three triangles, maybe the person’s name.

“It’s wearing clothes,” I added. A red lace sleeveless tunic fell to just below its body. I’d seen lace in computer texts.

The portrait went from hand to hand. “Almost a praying mantis,” Octavo said. Male or female? We didn’t know.

“There’s good hunting,” Julian said. “The glass makers had farms, and tulips and potatoes are still growing wild.” He was sticking to the plan. And Vera did what I’d expected.

“You ran away, and no matter what you discovered, you have to answer for that.” She was on her feet, waving droopy-skinned arms, the torn cloth in one hand. “You acted without concern for the welfare and interests of the Commonwealth as a whole. In four days, we’ll hold a meeting for judicial proceedings. Now it’s time to go to bed.”

The grandchildren whined.

“I’ll tell you more tomorrow,” I murmured to them.

Of course, there was a lot more to be told. Some of what we left out wasn’t much at all, like how truly miserable the hike back was. The moths bothered us less but the pulsing slime was worse. It had rained, and the water was higher in the river so the easy-walking sandbars had disappeared. We looked at the flotsam stuck in the tree branches above our heads and worried that a sudden storm might cause a flood. Our shoes had worn out, the packs were heavy with artifacts, and the stinking ground eagles remembered us as a source of trilobites and extorted meals.

The most miserable of all was the end of the bamboo fruit. We stretched it out as best we could but having only a little was as bad as having none at all. I was tired, I had headaches, I was hungry, and Julian felt just as bad.

“The only way to get more is to go back to the city,” I said one night in the hammock. “Not now, though. We couldn’t survive there alone, not forever. We need to move the village there, everyone. We need to live there.”

“The parents can’t make this hike.”

“Would they even want to come? I don’t think so.” I was quiet for a while, trying to conceive of life without them. Could they imagine the city, shining in the forest alongside the river? The city was big, really big … too big.

They knew about it. They had always known about it. They had been lying all our lives.

I lay silently, too shocked to think, while he stroked me under the blanket. “I wish they could see the city,” he said. “Then they’d come.”

“They’ve seen it in the satellite pictures,” I finally said. The satellite had surveyed the area carefully for resources. During our hike up the valley, Julian had told me all about a fault line that made the waterfall on Thunder River near the village and about the granite mountains that surrounded the plateau where the glass maker city was. He had a map with enough details to show the major cataracts in the valley and the river snaking through the forest in the plateau. The city’s roofs should have flashed out at any observer, but we used the meteorologists’ maps and had never seen the survey pictures themselves.

Julian figured it out fast. “They knew. Mom, Vera …”

“They saw it every day on the weather scans.”

“They knew. They covered it up. Why not tell us? Why?”

“We should ask them. But we should do it in a way to make people want to move to the city.”

I convinced him not to confront Vera right away although we wanted to when we got back to the village. We’d discuss her un-community-minded behavior at a Commonwealth meeting. I knew there’d be one and I was right.

Back in the village, the day after the little hurricane, we were answering questions even before we left the cellar. Julian went to hunt and I went to the plaza to make a couple of baskets to sift wheat, and a lot of people seemed to have tasks to do in the plaza.

“Are there fippokats?” asked little Higgins.

“Yes, and they play and slide just like here.”

“Is the soil good?” a farmer asked.

“Well, the trees are bigger.”

“How was the climate?”

“You’d have to ask Vera, she has the weather data, but it seemed cooler and damper. The fields wouldn’t need irrigation. And we know hurricanes break up on the mountains, so we wouldn’t have to worry about them anymore.”

“Were there ground eagles?”

“Probably, but the town has a wall around it.”

“What happened to the glass makers?”

“Maybe an epidemic, or maybe they moved and live somewhere else.”

“How much bamboo fruit was there?”

“Plenty.”

I learned that while we were gone, the tomography machine had failed for good, Nicoletta’s father had died of space travel cancer, and a new kind of lizard had been discovered, tiny and iridescent yellow, that fertilized tulip flowers.

I folded in the spokes to finish the first basket and I measured and cut reeds for the second one. “The rainbow bamboo probably wants what the snow vine does,” I said, “gifts and a little help.”

“Was it beautiful?”

“You can’t imagine.”

Ramona limped up to us, leaning on a pair of canes and draped in a shawl. It was odd to see her out of the clinic where she worked and at first I thought she’d come to hear about the city, but she looked too sad. Maybe another parent had died and she’d come to tell someone. But she came over to me.

“Sylvia, I’m so sorry,” she said. She leaned against my worktable and took my hand. Hers was cold and twitched with Parkinson’s disease. My parents were dead, so what could she be so sorry about?

“Julian is dead. He made a mistake with a poisoned arrow.” She went on to explain but I hardly heard her. Julian was dead. Julian.

That couldn’t be right.

Ramona hugged me. She was thin and shaking. “I’m sorry. I know you’d gotten close.”

I tried to talk and realized I had stopped breathing. I deliberately took a deep breath. “What happened?”

“He died. Julian died when he was hunting.”

“How?” Even with one small syllable, my voice shook.

She explained again and I made myself listen. She said it was just a hunting accident in the forest near the lake. He was putting a poisoned arrow on his bowstring and it slipped. But she was lying, I knew it, another lying parent. He’d never have made a mistake like that. He was a fine hunter, as silent as an owl in the woods.