По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

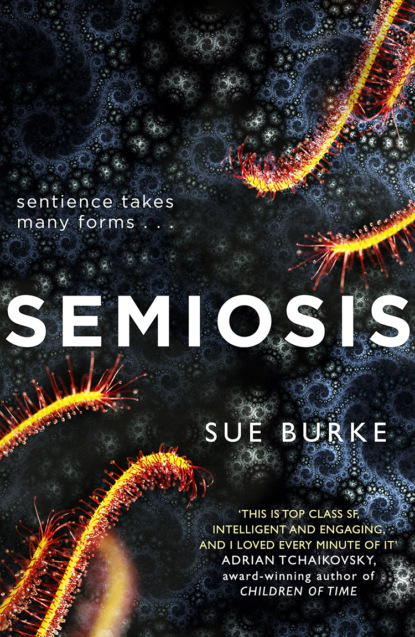

Semiosis: A novel of first contact

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She shook her head and closed her eyes and sighed. “This is hard, so hard.”

“I found this.” I held out the ball. Maybe it would cheer her up. She opened her eyes and stared at it blankly. “I think it was made by some other intelligent life,” I said. “It was at the lake.”

Terrell had come up behind her. He was a parent and metallurgist, so I said, “That’s gold around it. We should look for whoever made it.”

He was tall and as thin as a parasitized aspen, so when he nudged Vera, she had to look up to see his face as they exchanged a look. They were interested so I pulled out some rainbow twigs.

“I found these, too.”

They stiffened with surprise, but Vera said, “We don’t have time for that, not now. There’s too much to do.” She took the ball from my hand. “I’ll put it on the agenda for the next meeting.”

But the next Commonwealth meeting was in four days. Four days!

Still, people heard about the ball and wanted to see it that night in the dark cellar as we ate dinner.

Ramona said, “It looks like a Christmas ornament,” and she began to sing a Christmas song, but Bryan, another parent, complained that Christmas was a nightmare.

“Arguing over the past,” said Rosemarie, a child a little older than me, and Bryan overheard and scolded her for disrespecting the parents. I’d read about Christmas and “frivolity” was the word I remembered, and frivolity seemed interesting. And unlikely on Pax.

Survival first. There was a lot to repair and replant but there always was. “Is this really better than Earth?” Nicoletta had whispered once when we were young and no parents were around. Now, she worked as my mother’s replacement, scavenging parts from the failed radio system to repair the medical tomography equipment, and if there were parts left over, to keep the weeding machines running. Machines did mindless tasks so we had time to care for sick parents or prepare for the next storm or preserve what food we had for winter.

Nicoletta had borne three babies already and two lived. When we were young, we used to coil her curly black hair into ringlets. These days, she had no time for fussing with her hair. And sometimes she cried for no reason.

Daniel fished but the lake became anaerobic during the bad droughts and all the fish died. My brother tried to enrich the soil in the fields and complained that the snow vines took the nutrients as fast as he could fertilize, but snow vine fruit kept everyone fed when crops failed or were destroyed by storms.

Sometimes, Octavo would stare at nothing and grumble: “Parameters. Fippokats here. Uri, let’s go weeding.” Uri had died ten years ago. Octavo was sick and would die soon too, and I’d miss him because he was always patient with me.

I was in the plaza weaving a thatch frame for a temporary roof for the lodge when Octavo limped up to ask for a sample of the rainbow bamboo, as he called it.

“Something for the meeting,” he said, and coughed with a wheezing bark. “Something that needs an explanation.” He knew plants better than anyone and I wondered what there was to explain.

But thunderstorms arrived on the meeting night and no building could hold all residents at once, although we were only sixty-two people. The roof thatched with plastic bark on my lodge held with hardly a leak and some people congratulated me, but not Vera. She was still proving she was moderator and reorganizing our rooms because a lot of them had been damaged in the big hurricane, even though we’d already rearranged ourselves without her help and no one was complaining.

I went to the closet that was my new room, with nothing but a cot and one box that held everything I owned, so angry I almost cried. I should have known then what I realized later, that we wouldn’t have voted to investigate the glass makers anyway. The parents would’ve voted no, the children would’ve voted the way their parents did, and even the grandchildren would follow their parents’ parents. Children didn’t think for themselves. We did what we were told because we’d been convinced that we didn’t really understand things well enough to make our own decisions. That’s what we were told all the time and how could we argue with that? We were supposed to be happy to be just like the parents, and working together in harmony mattered more than thinking as individuals. We were still children even though most of us were twenty or thirty years old.

What would happen when all the parents died?

Octavo came to talk to me the next day while I was working in a corner of the plaza next to Snowman, the big old snow vine. I was making a basket for collecting pond grubs, a wide hoop basket with loosely attached ribs so it would be soft and flexible because the grubs burst so easily. I was thinking about the meeting we should have held. Why wasn’t Vera interested in something as big as another intelligent species nearby when something as small as who slept on the sunrise side of a lodge fascinated her?

I could hear her laughing as I worked. She was sitting with some other parents at the far corner of the plaza cleaning trilobites, stinky work, so they were as far from the lodges and the meal area as they could get and I couldn’t hear the words, just occasional laughter. She always worked hard and the parents and some children liked her leadership and I still wanted to like her but all I had were questions.

Octavo lowered himself onto a bench, panting. I pulled out some cois twine and anchored the ribs first on one side of the hoop and then on the other. He couldn’t tolerate certain fungus spores and his lungs had been regrown three times but they worked less efficiently each time. The same thing had been killing my father, Merl, when a pack of ground eagles got him first. Our hunters tracked down the pack, the last one to bother us, and we put a bouquet of spiny eagle feathers on Papa’s grave.

“A Coke would be nice right now,” Octavo finally said. Coke was some sort of Earth drink. “You know, snow vine fruit looks a lot like that glass ball, those same surface facets when they’re immature.”

I glanced up. “Is that important?”

He pulled out the rainbow bamboo twig I’d given him. “Pax is a billion years older than Earth. It has had time for more evolution.”

I finished a weaver and reached for another, thought again, and picked a coil of greener cois so I could make a striped basket. “We should find the people who made the ball.”

“It might not be that easy, girl. There are two intelligences. The ball is obvious, but the bamboo … It belongs to the snow vine family. We set fippolions to graze on the west vine and the east vine rejoiced. Our loyal master …”

He paused again to catch his breath and gazed across the plaza. I kept weaving, wondering why he was complaining about the snow vines again.

“This bamboo,” he said, “displays a representation of a rainbow, not a refraction like the surface of a bubble. This is made with chromoplasts. Plants can see. They grow toward light and observe its angle to know the season. They recognize colors. This one made colors on its bark to show something. It is a signal … that this plant is intelligent. It can interpret the visual spectrum and control its responses.”

“So it wants to attract us? Attract intelligent beings, I mean?”

“No. A signal to beware. Like thorns. Who knows what a plant might be thinking? I … doubt they have a natural tenderness for animals. We are … conveniences.”

“But the glass ball is beautiful. It’s a fruit, you said, so it must have come from a plant that was friendly or the glass makers wouldn’t have made such a nice copy of it. Maybe it came from the rainbow bamboo, since it’s like snow vine fruit. We should find it.”

Octavo was staring across the plaza. Vera was getting up. He turned to me. “Snow vines are not especially intelligent, less than a wolf. Well, you have never seen wolves or even dogs … But this rainbow bamboo … You can predict animals but not plants. They never think like we do. It might not be friendly.”

“If the snow vines can decide to give us fruit, then the rainbow bamboo might give us fruit, too. We always need food and a more intelligent plant would know how much we can do for it in exchange for food.”

“Exactly, plants always want something.” He glanced at Vera, who was walking toward us. “But this cois twine … Tell me, have you noticed a difference in fibers in the different colors?”

I frowned. Why was he asking that? But I wanted to be polite so I picked up samples of each color and flexed them. “No. I think the greener is just picked younger.”

Vera came up to us and stopped.

Octavo looked at her. “We have been discussing cois. It could have many uses, perhaps like flax … We have been too focused on food sources, I think.”

“We always need food,” she said.

They were silent for a while and since I wouldn’t be interrupting, I said, “I’ve been thinking about the glass and rainbow bamboo. When can we discuss it at a meeting?”

“Not soon,” she said. “We still haven’t recovered from the hurricane.”

I tried to hide my disappointment, but she was staring at my basket instead of me anyway. The stripe looked good.

“That’s the natural variation of the cois fiber,” I murmured.

“Efficient,” she said, and hobbled away.

“We’ll never discuss it!” I said. “Paula wasn’t like that.” Octavo never scolded when we children complained.

“Paula had … training.” He looked at the twig. “Not our planet, not our niche.”

“Intelligent creatures have no niche.” I’d read that somewhere.

Octavo shook his head. He never really liked plants even though he was a botanist, and it was no good arguing with him. He had me help him get up and he went to the lab.

I kept working on the basket and I tried to imagine plants as smart as we were. How would they relate to us? Probably not the way regular plants acted toward bug-lizards or fippokats. And I could make beautiful things with rainbow bamboo. Why wait? I got some twigs from storage, soaked them, and when the grub basket was done, I took a twig, made two loops, and then braided the end through the loops. A colorful bracelet, a whole minute wasted on a decoration. I made seven and set them to dry in the Sun with the basket.

I gave the soaking water to Snowman, put my things away, helped erect a bower to shade some lettuce seedlings, and delivered the basket to Rosemarie and Daniel. I returned to the bracelets, put one on, and gave others to Julian, Aloysha, Mama, Nicoletta, Cynthia, and Enea.