По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

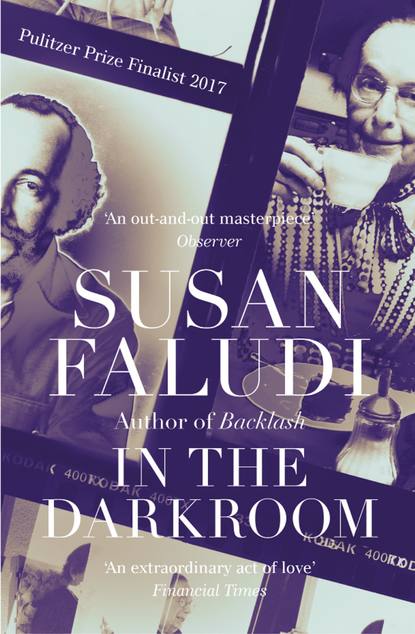

In the Darkroom

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The longer we spent in the third-floor garret viewing virtual non-reality, the more frantic I became to escape into the world beyond the perimeter. If I stood at the attic window and stretched on tiptoe, I could just make out, over the chestnut and fruit trees and down the sloping hills and across the river, Pest, that fabled cosmopolis, the historic venue of so much creative and cultural ferment. At the turn of the century, Pest had been host to a spectacular upwelling of artists and writers and musicians whose works had packed the museums and bookstalls and concert halls, who’d painted and scribbled and composed in the six hundred coffeehouses, published in the twenty-two daily newspapers and more than a dozen literary journals, filled the more than sixteen thousand seats of the city’s fast-proliferating theaters and opera and operetta houses, and transformed the identity of the long backward capital into the “Paris of Eastern Europe.” The city in my mind was the one I’d read about in John Lukács’s Budapest 1900, the one the London Times correspondent Henri de Blowitz described in the late 1890s: “Buda-Pest! The very word names an idea which is big with the future. It is synonymous with restored liberty, unfolding now at each forward step; it is the future opening up before a growing people.” Blowitz’s city, I knew, belonged to a time long past. Still, my mind somehow wanted to hitch the city’s old aspiration to my father’s current one. Even when I was growing up, I’d felt that a key to my father’s enigma must lie in that Emerald City of István Friedman’s birth. I still couldn’t dispel the notion that to understand Stefi, I had to see her in the world where he was from, visit the streets and landmarks and “royal apartment” that little Pista had inhabited. But Pest was down the hill, visible only on tiptoe.

On those mornings when we weren’t lost in NASA rocket launches or Gender Heaven beauty tips, we were inspecting the images she’d assembled under “My Pictures.” Few of them were actually her pictures; most had been lifted from the Web. An exception was her Screen Saver image, a photo of a servant girl in a French maid’s outfit, a pink bow in her platinum blond curls. She had one white stiletto heel thrust out and was reaching down to adjust a stocking. The chambermaid was my father, who’d taken a selfie standing in front of a mirror.

Then there were the montages: images she’d pulled from various Internet pages, into which she’d inserted herself. All that long experience doctoring fashion spreads for Vogue and Brides had found its final form: Stefi’s face atop a chiffon slip originally worn by a headless mannequin. Stefi implanted on the long legs of a woman ironing lingerie in a polka-dot apron. (“I added the apron,” she said.) Stefi transported into an online Christmas card of a girl wearing a red ruffle around her neck and not much else. Stefi in a pink tutu and ballet slippers, captured in mid plié. Stefi in another maid’s outfit, this one belonging to a little girl, who was being disciplined by a stern schoolmarm in tweeds and lace-up boots. The girl held the skirt up in back to reveal her frilly underwear.

“I did these before I had the operation,” my father said, “but it was too extreme. Transvestite pretension.”

The theme of “before” and “after” was a recurrent one in these viewing sessions. My father seemed intent on drawing a thick line between her pre- and post-op self, as though the matron respectability she’d now achieved renounced her earlier sex-kitten incarnations, made them into a “flamboyance” that she no longer needed or recognized.

“What’s that?” I asked, pointing to a link she’d bookmarked called FictionMania. I was hoping for narrative relief from the onslaught of images. “Oh, people make up these stories about themselves and post them on this site,” she said. “We don’t need to look at that.”

“Stories?” I pressed. I’d look it up later: FictionMania was one of the largest transgender fantasy sites on the Internet, a repository for more than twenty thousand trans-authored tales, the vast majority of them sexual. A popular story line involved a dominatrix (often a female relative) forcing a cowed man into feminine undergarments, dresses, and makeup. The genre had a name: “Forced Feminization Fiction.”

“You know, stories,” my father answered, “like they’re little boys and their mothers make them dress up as a girl as punishment and then their mothers spank them. And they have illustrations.” I reached for the mouse to click on the link. My father pushed my hand aside. “I wouldn’t even share that with a psychiatrist.” Not that she had one; she regarded psychiatry as one of those “stupid things” best given a wide berth. I asked if she had ever posted a story on the site.

“No, I just used some of the pictures they have on here. For my montages,” pasting her face onto one or another costumed playmate. She’d done more than that, though. Her upstairs hall closet contained stacks and stacks of file folders of forced feminization dramas she’d downloaded from FictionMania and similar sites, in which she’d montaged her names into the text (Steven “before,” Stefánie “after”). Her stash showed a predilection for subjugation and domestic service, often set in Victorian times: “Baroness Gloria, the Amazing Story of a Boy Turned Girl” (in which Aunt Margaret in Gay Nineties Berlin disciplines her nephew into becoming a corseted “real lady”) or “She Male Academy” (in which Mom sends her misbehaving son to the Lacy Academy for Young Ladies, a “vast mansion designed in the Victorian Gothic manner,” where whip-wielding mistresses exact a transformation: “Steven will become Stefánie; his bold, brash and arrogant male self will be destroyed and replaced with the dainty, mincing and helplessly ultra-feminine personality of a sissy slave girl”). Along with the altered downloads were a few stories my father had written herself. Her character stayed true to form, submitting to the directives of a chief housekeeper while an all-female crew of iron-handed maids order “Steven” into baby-doll nighties, Mary Jane shoes, and a French chambermaid’s uniform.

At the computer, my father had moved on to another page of links. “I haven’t looked at that website for two years at least,” she said of FictionMania. “It was just a—, like a hobby. Like I used to smoke cigars, but I gave it up. This was all before.”

“And now?”

“Now I’m a real woman,” she said. “But I keep these pictures as souvenirs. I put a lot of work into them; I don’t want to throw them out.”

She hadn’t stopped montaging; she’d only shifted genres. She showed me a few of her more recent constructions. Now she was the lady of the house: Stefánie in a long pleated skirt and high-necked bodice. Stefánie with hair swept up into a prim bun and holding the sort of large sensible pocketbook favored by Her Majesty the Queen of England. This was certainly a persona shift from the “sissy slave girl” in Mary Janes, or at least an age adjustment. And yet, it seemed less a repudiation of her erotica collection than a culmination of it.

The sex fantasies and lingerie catalogs in my father’s file folders in the hall closet were commingled with printouts of downloaded how-to manuals on gender metamorphosis (“The Art of Walking in Extreme Heels”), many of them narrated by virtual dominatrixes: “This is your first step on your journey into femininity, a journey that will change your life,” read the introduction to “Sissy Station,” a twenty-three-step electronic instructional on “finding your true self” by becoming a woman. “You will be humiliated and embarrassed. Most of all, you will be feminized.” The journey required, in different stages, applying multiple coats of red toenail polish every four days, beribboning testicles, and practicing submission with sex toys before a mirror.

“There isn’t any one way to be a trans,” a trans friend cautioned me some years later. “I think of transsexuality as one big room with many doors leading into it.” My father’s chosen door was distinct. But the big room, like any condo, had its covenants and restrictions. A reigning tenet of modern transgenderism holds that gender identity and sexuality are two separate realms, not to be confused. “Being transgender has nothing to do with sexual orientation, sex, or genitalia,” an online informational site instructs typically. “Transgender is strictly about gender identity.” Yet, here in my father’s file folders was a record of her earliest steps toward gender parthenogenesis, expressed in vividly sexual terms. And here in FictionMania and Sissy Station and the vast electronic literature of forced feminization fiction was a transgender id in which becoming a woman was thoroughly sexualized, in which femininity was related in terms of bondage and humiliation and orgasm, and the transformation from one gender to another was eroticized at every step. How to tease the two apart?

My father clicked the mouse and a greeting card popped up: Stefi’s visage pasted onto a frilled lace gown, hands clutching a bouquet, above the card’s preprinted message, “Wish I could be a bridesmaid on your Wedding Day!”

“You sent this card?”

“Not this one. I’ve sent others.”

“To?” Who, I wondered, was the bride she wished she “could be a bridesmaid” for?

“Other trans friends,” my father said.

“People you know?”

“People who have websites. You know, ‘Internet friends.’”

My father had bookmarked some of these “friends’” websites: Annaliese from Austria who, according to her page, “dresses sexy,” is “a size 12,” and “loves to go shopping.” Margit from Sweden, who “loves” bustiers, plush teddy bears, and “the color pink.” Genevieve of Germany, whose blog featured shots of herself topless on a nude beach and a timeline of “my second birth.”

“These pictures aren’t retouched,” my father said, unimpressed. “They aren’t as good as mine.”

“Where are your family photographs?” I asked. Suddenly, I’d had all I could handle of bustiers and second births. “From your childhood.”

My father gave her dismissive wave. “I don’t look at those.”

“But where are they?”

Silence. Then, airily: “Oh, somewhere.”

“Somewhere where?”

She shrugged, kept clicking through her images. Finally: “I keep all the old stuff, the important documents, in the basement. In a lockbox.”

“Could I see them?”

“It’s irrelevant,” she said. “It’s not me anymore.”

I looked at the clock; the day was half over. Day Five in the fortress.

“Dad, Stefi, please,” I said. “Let’s go out. You can show me the places you love in the city. Show me where you used to go in Pest as a child.”

“It doesn’t pay to live in the past,” my father said. “‘Get rid of old friends, make the new!’”

“I don’t think that’s how it goes,” I said. At any rate, I was here to see if I could make a new sort of friend: her. If only she could drop her age-old obstinance long enough to allow it. But our interactions were persistently one way: instead of mutual exchange, a force-fed guided tour of frou-frou fashions and hard-drive fantasies. When was she going to let in the daughter she wouldn’t let out?

“I don’t want to go to old places,” my father said. “It’s not interesting.”

“It interests me,” I said, hating my whininess, my own age-old obstinance.

“You are off the subject,” she said, tapping an insistent pink-polished nail on my notepad. “I’m Stefi now.”

One late afternoon, we stood in the kitchen, my father peeling an apple with her latest Swiss Army pocket knife. It was the “ladies’” version, she noted, with an emery board and cuticle scissors.

“Can I ask you a question?” my father said.

I nodded, hopeful. She was never the one who asked the questions. Maybe this was the start of an actual conversation.

“Can you leave your door open?” she said. “You close it every night when you go to bed.”

I drew back, speechless.

“Can you leave it open?”

“Why?”

“Because I want to be treated as a woman. I want to be able to walk around without clothes and for you to treat it normally.”

“Women don’t ‘normally’ walk around naked,” I said.

The blade snapped shut, and the conversational opportunity, if that’s what it had been, shut with it. She returned her ladies’ knife to an apron pocket.

That night, I closed the bedroom door. Then I reconsidered, and opened it a crack. As much as her intrusions disturbed me, I sensed that she wasn’t really targeting me. Or, if she was, it was only me as a mirror. After a while, a hesitant knock.