По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

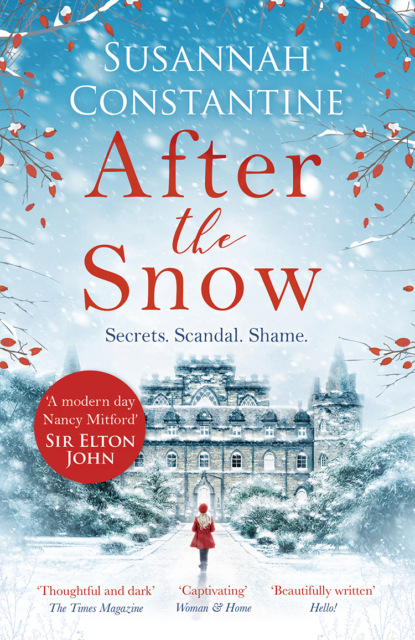

After the Snow: A gorgeous Christmas story to curl up with this winter 2018!

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

After what felt like miles of walking, the castle finally rose into the sky before her and she soon reached the drive. There were already a lot of cars there and she could hear the party in full swing. As she pushed open the front door she wasn’t sure whether it was a blast of warm air or a sense of relief that washed over her.

Pulling off her own sodden boots, she noticed her sister’s coat had fallen off its hook and landed in a dark pool of water on the rush matting.

Serves her right for not waiting for us, Esme thought, although she still picked it up and placed it alongside her own coat on the cast iron radiator.

The sound of laughter and clinking glasses trickled down the hallway from upstairs. She knew all her family would be safe and warm in the drawing room, probably each already on their third mince pie. She ran up the corridor and bound up the staircase, two steps at a time. At a drinks table on the landing stood the Culcairns’ butler, Mr Cribben. He was taking a deep swig from a crystal decanter, which he hurriedly put down. He wiped his mouth with the sleeve of his tailcoat.

‘Esme! Merry Christmas. Would you care for a drink?’

‘Yes please, Mr Cribben. A bitter lemon please. Have you seen my family?’

The butler snapped the lid off a small Britvic bottle with a silver opener disguised as a duck’s head.

‘Yes,’ he hiccupped. ‘I believe they are in there already.’

‘Thanks, Mr Cribben, and happy Christmas to you too.’ Esme took a gulp of her drink, the bubbles getting up her nose and making her cough.

Entering the warm glow of the drawing room, she peered through the throng of guests, trying to find her family. This was the grandest reception room in the private side of the castle and Esme’s favourite. It was so big that it had two marble fireplaces and not one but two enormous Christmas trees. Both were festooned with silken bows and golden baubles, real candles flickering dangerously close to the thick boas of tinsel. Piles of extravagantly wrapped presents lay beneath them.

Esme saw Sophia and Rollo talking under some mistletoe and wondered if they might be about to kiss. Cheerful faces, many of whom she recognized, occupied ornately carved sofas and chairs upholstered in pale-blue silk. She caught sight of the Earl talking to Father Kinley, Lord Findlay in conversation with Lord and Lady Robert Fraser, then her father appeared, breaking away from the crowd, gripping a steaming cup of mulled wine.

‘Darling, there you are. What took you so long?’ he asked, crossing the carpet and ruffling her hair.

‘Why didn’t you wait for us, Daddy? Mummy lost her shoe and I couldn’t find it. Is she here?’

‘Oh, I’m sure she’s here somewhere,’ said her father, gesturing his hand around the room. ‘Probably powdering her nose after being out in the snow for so long. Why don’t you go and find Lexi?’

Yes, Lexi, Esme thought, excitedly. She squeezed into the crowd, parting ladies’ skirts with her hands as she tried to get to the back of the room where the children usually played. Lexi was her best and only real friend. Unlike the girls at her London school, Lexi liked to do the same things as her. They weren’t interested in pop stars or boys and didn’t give a monkey’s about how they looked. As long as they had each other and their ponies, they were happy.

‘Rraaaah!’

Esme jumped as two hands covered her eyes.

‘Lexi!’ Esme squealed, spinning round and putting her arms around her friend. ‘Oh Lexi, happy Christmas! Isn’t the snow amazing?’

‘I know! But are you OK? Sophia said your car crashed into a ditch and you had to walk all the way to the castle.’

‘Yes, it was a terrific adventure, Lexi, and most of it I had to do on my own because Mummy went missing! But Daddy says she’s probably powdering her nose now – have you seen her?’

‘No, not yet,’ said Lexi.

‘Oh look!’ It was Bella. ‘Sausage rolls.’

Bella was born hilarious, wise – and thalidomide. Esme’s mother had told her that thalidomide was a pill that some women had taken to stop feeling sick when they were pregnant because the doctors hadn’t known it was dangerous or that it would make babies’ arms stop growing. Esme was amazed how well Bella managed without arms. She had even stopped noticing sometimes.

‘Happy Christmas, Bella,’ said Esme. ‘Do you want me to get you one?’

‘Not one, stupid. Ten – at least!’

The girls pushed their way over to Mr Cribben, who was swaying through the room carrying a precariously balanced silver try laden with the shortcrust pastry parcels. Grabbing a handful, half of which Esme gave to Bella, she and Lexi then retreated under the grand piano so that they could talk properly.

‘What did Father Christmas bring you, Lexi?’ Esme asked, through a mouthful of crumbly pastry.

‘Well, the best present was a stable rug for Jupiter, embroidered with his name! Oh, and I was given a subscription for Horse and Hound so we can see where all the pony club events are in the summer.’

‘Amazing!’ Esme grinned. ‘Let’s try and get our pictures taken jumping a huge hedge when we go hunting. Didn’t you say they were sending a photographer up here for the New Year’s Eve meet?’

‘Yes, definitely. Papa will be attending so at the very least we’ll get a photo if we stand next to him. Homer and Jupiter will be famous!’

‘Oh and I almost forgot! Lexi, Father Christmas gave me a dandy brush just like yours! Homer will look so handsome in the photos.’

Lexi smiled back at her and said in a deep voice, ‘Lady Alexa Culcairn on Jupiter and Miss Esme Munroe on Homer taking their own line at Smythe Thorns.’

‘We’ll be the talk of the town!’ Esme said, gleefully.

Stuffing another sausage roll into her mouth, she peered out from under the piano, half expecting and vaguely hoping to see her mother drying out by the fire. She heard her father’s bellowing laugh from across the room. If he didn’t seem worried about her mother, then everything must be all right.

Lexi and Esme continued their unspoken mission to finish off all the sausage rolls, sipping their bottles of bitter lemon between bites.

‘Did you see Rollo and Sophia under the mistletoe? Maybe they’ll fall in love and get married?’ said Esme.

‘And then we really will be proper sisters! Perhaps we can be bridesmaids together. Let’s go and draw our dream dresses,’ said Lexi. ‘I got some new Caran d’Ache in my stocking.’

After riding horses, drawing made-up outfits with Caran d’Ache colouring pencils was Esme’s favourite thing in the world to do and she was saving her pocket money for a new tin.

Just then, the other conversations in the room fell away at the sound of the Earl’s voice booming out, and Esme looked up, startled.

‘What do you mean you left her in the snow? How could you be so bloody irresponsible, Colin?’

‘Esme was with her and I assumed she was already here and powdering her nose,’ Esme heard her father reply.

‘You’ve already been here for nearly an hour! Diana would never spend that much time on her appearance, so where the hell is she?’

Esme froze. Where was her mother? It was her fault, she should have looked harder – until she found her.

‘Stop shouting, Henry,’ said the Contessa. Then, in a quieter tone, ‘Colin, I can’t believe you left Diana like that, especially with her being the way she is right now.’

‘It’s not as though she hasn’t been here before!’ said her father. ‘And like I said, Esme was with her. Sophia and I were only just ahead. Never crossed my mind that she might get lost and I don’t suppose she is now.’

‘No, Colin,’ replied Henry, his voice hard. ‘She might have frozen to death out there. I will go and search for her myself.’

‘Oh Henry,’ said the Contessa. ‘Don’t be so utterly ridiculous. We have all these guests here. Just send Miller.’

Esme crawled out from her hiding place and rushed to her father’s side. She wished Sophia was with her but she was probably somewhere with Rollo and his friends, smoking or doing whatever it was they did in her smoochy novels.

‘Daddy! We should go and find her. It’s all my fault. I lost her like the shoe.’ She looked up at her father, holding her breath and tears.

‘Esme, you lovely girl,’ said the Earl. ‘Why don’t you and I go and find your mother together? Colin, Lucia, you stay here and enjoy yourselves.’