По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

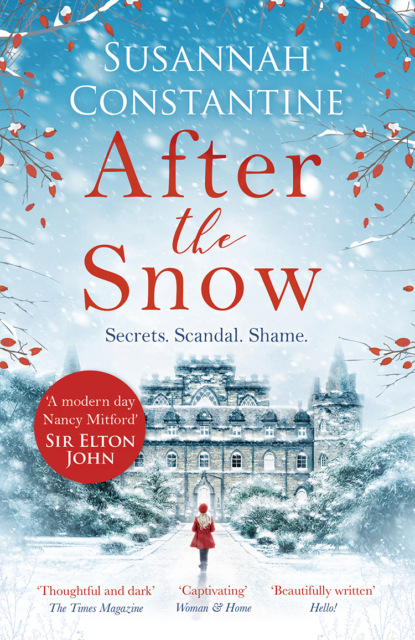

After the Snow: A gorgeous Christmas story to curl up with this winter 2018!

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Because it saw The Queen Mary’s bottom. That’s so old,’ groaned Esme, copying her sister, although she actually thought that the picture of Queen Mary in her frilly underpants was very funny.

They all put on their paper crowns, Esme carefully placing one on her mother’s head. It sat lopsided and made her look like a forgotten toy.

‘All right, plates down. Time for presents!’ announced Esme’s father, as they finished their puddings.

Normally, presents were opened before the Queen’s Speech, but the Queen had given a written address instead this year, following a documentary that had aired about the Royal Family a few months previously. Esme was disappointed that they didn’t get to see Her Majesty, although she supposed she always looked the same. An embroidered dress and pearls, a stiff hairstyle and a small smile. Without the Queen, the world would stop turning, Esme thought. She wondered why she never wore her crown in public. If she were the Queen, she’d make sure she put it on every day. Her father always said that Queen Elizabeth was a handsome woman but not nearly as attractive as her sister, Princess Margaret. Maybe people said the same thing about her and Sophia, but Esme didn’t think that either of them was particularly handsome. That was for boys. Lexi had mentioned that the Princess was coming to stay at Culcairn Castle in a few days’ time, so she could decide who was the more attractive sister then.

Mrs Bee ushered everyone into the drawing room, where Esme dropped down next to the gigantic Christmas tree. Every year, her father would go about the dressing of the tree in the same meticulous fashion, while she and Sophia passed him the decorations. First the lights, which were small and white, had to be wound from the top down, ensuring that each layer of branches was equally illuminated. Then came the tinsel; finely woven pieces of silver had to camouflage every inch of the ugly white wire to which the lights were attached. Once this had been achieved – which took a good two hours to ensure perfection – glass baubles collected from all corners of the globe or handed down to them from past generations were hung equidistant from each other in order of size and colour. Holding the tree steady was the sand-filled bucket in which it stood, which was wrapped in golden paper that splayed out around the base in a skirt. An assortment of mismatched gifts lay in the pool of shimmering paper. There was nothing haphazard about the Munroes’ Christmas tree; it had to be visually faultless and decorated in the best possible taste.

Esme’s father was very artistic and loved to paint. Many of his paintings adorned the walls of The Lodge and their house in London. Esme thought that if he spent all his time painting rather than organizing the transport of important paintings all around the world he would be much happier. He loved to talk about art and knew so much about it. Esme loved to sit alongside him whilst he painted, drawing her own pictures and listening to him recounting tales of great artists.

As her father began to hand out the presents, Esme felt a familiar embarrassment that they had so much and Mrs Bee had so little. Even though Mrs Bee frequently told her ‘I’m short of nothing but money’. Quickly, she handed a present to the housekeeper, which Mrs Bee duly unwrapped.

‘Oh, thank you, Mrs M,’ said Mrs Bee, delighted with her cardigan. She looked over to Esme’s mother, who was sitting listlessly in a high-backed embroidered chair. ‘Why don’t you hold the bag for the wrapping paper?’ she asked her.

Seeing that Mrs Bee was trying to engage her mother, Esme picked up the bag and held it out. ‘Mummy, hold the bag open so we can get the paper in easily.’

Diana picked up the other handle in slow motion.

‘Come on, wakey-wakey – it’s not bedtime yet,’ said Sophia, giving her mother a prod.

She stirred and looked over at Esme. ‘Darling, you’d better get a pen and paper so you can jot down who’s given you what – for your thank-you letters.’

Esme hopped up and ran to the desk, flipping its lid back in search of a sheet of writing paper and a biro. Plonking herself back down she waited to be passed her first present.

Darling Esme, Happy Christmas, lots of love Aunt Nancy, read the label.

Aunt Nancy was the youngest of her mother’s three sisters. Her father was also from a big family, with three brothers and one sister. Because there were so many of them and none had a house large enough to accommodate the whole family at once, they would try to meet up elsewhere in the summer holidays instead. Esme loved spending time with all her cousins. But that didn’t happen very often. Both sets of grandparents had passed away before Esme was born. She envied Lexi and her extended family, who all lived nearby.

Aunt Nancy always gave good presents and this year was no exception; she had given Esme The Mandy Annual. Mandy was Esme’s favourite comic, the one she spent her pocket money on each week.

‘Sophia, look – this one’s from your godfather, Bill,’ said Mrs Bee, handing her a beautifully wrapped parcel.

Esme knew it would be something elegant and perfectly chosen. Her father’s oldest friend from his school days at Eton was seriously rich and very generous because he had no children of his own.

Sophia squealed as she unwrapped an Afghan coat from its tissue. It was a thing of real beauty. Embroidered down the front, a bit like Esme’s Red Indian jacket, it had shaggy sheepskin cuffs and frog fastenings that gave it a Russian flare. Sophia hugged it and spun around the room, using the coat as her flamboyant dancing partner. Her face was alight with joy as she grinned and twirled around and around.

‘Oh Es, look at this! Isn’t it the most divinely wondrous thing you’ve ever seen? Feast your eyes! Darling Bill is the best! Daddy, are you furious? I know you think that only drug-taking hippies wear this sort of thing but I love it; you’ll have to blame your best friend for being so utterly, utterly adorable! He is the best and kindest fairy godfather in the world!’

Her father laughed. ‘You’ll get arrested wearing that around here. You might as well go and live on a commune and hug trees. I need to have words with Mr Bill Cartwright. He is incorrigible. Don’t wear it anywhere near me. People will think I have a commie as a daughter.’

‘Oh Daddy, you’re so square. I shall wear it day and night.’

‘You’ll soon tire of it. But you’ll never get bored of our present to you.’ With that, Colin handed her a large, heavy-looking square package. Sophia ripped off the paper.

‘Oh Daddy, I can’t believe it!’

It was a red record player with a lid that doubled up as a speaker. Esme knew her sister had wanted one of these forever, collecting all kinds of music for the time she could play the records on her own turntable. Esme hoped that her present from her parents would be just as exciting. Perhaps, just perhaps, it would be a velvet hunting cap from Patey’s. Her mother had pointed out the rip in her old hat so knew she needed one. Esme was old enough now to wear one without a chinstrap. Knowing it was her turn next she sat expectantly, her tummy fluttering with excitement.

Her father rummaged through the dwindling pile of gifts.

‘Diana, where is Esme’s present?’

‘It should be there. Is it not?’

‘You said you wrapped it last night. Darling, Mummy bought your present. Diana, go and see if it’s upstairs.’

Dropping the bulging Harrods bag, Diana rose slowly and left the room.

‘Darling, Mummy will find it – don’t look so worried. She told me she had bought you something wonderful.’ Colin glanced up at Mrs Bee.

‘Open this one from me,’ said the housekeeper, hurriedly, to Esme.

‘Thank you, Mrs Bee.’ She looked down to hide the hot tears that welled in her eyes and started to fall on to the parcel with a tell-tale splash as she tore open the wrapping paper.

‘Mrs Bee, these are just what I need. Thank you so much! They’re even better than the ones I lost and will keep my hands cozy out hunting. Thank you.’

She got up and hugged Mrs Bee as though her life depended on it. The housekeeper hugged her back, Esme’s tears concealed in the crook of her neck.

‘Here we go, darling, here’s your mother,’ she said.

Esme peered over Mrs Bee’s shoulder to see her mother standing in the doorway, empty-handed and dry-eyed.

Chapter Four (#ulink_84806bc8-ae66-5058-827b-8a7a89a0d8ec)

Esme wrenched herself from Mrs Bee’s embrace, barged past her mother and shouted for Digger. She pulled on her wellies, grabbed her coat and ran into the cold twilight, ignoring her father’s appeal for her to come back. This was turning out to be the worst Christmas ever and she needed to get away, to be in her secret place. Hot tears froze against her skin as she tried to catch her breath.

It wasn’t even the present. Her mother had forgotten her. Why hadn’t her father taken charge like he had with Sophia? It wasn’t that Sophia was her parents’ favourite because they usually treated them both equally and she was pleased that her sister had got the present she wanted. She also knew she was luckier than lots of other children, but it made her feel small, invisible even, that they had forgotten to buy her a present.

As Esme walked through the orchard the moon cast enough light for her to see her way into the thick woods surrounding The Lodge. She felt safe and her tears subsided. The trees were her allies, keeping her hidey-hole secret from her family. Lexi and Sophia knew where it was and Esme wished her sister were here with her now. Only she would really understand how sad Esme was feeling.

She strode across the hardening snow, Digger bounding alongside her, her boots and his paws leaving barely a trace. Despite the ghostly white covering that changed the wood into a foreign landscape, she had no trouble finding the entrance to her place of escape. Hidden behind a thicket of ancient brambles and rampant foliage, she pushed her way through and opened the crudely made door.

The old Victorian summer house had lain derelict when Esme chanced upon it one day when searching for Digger, who had gone missing on a wild rabbit chase. She called the summer house her ‘secret place’. It was her home from home, somewhere she could escape to when she was upset. Here, she was in charge and could do and feel as she liked.

She lit a candle that had been stuck onto an old saucer and was lying on the windowsill with a box of matches.

The room was filled with a tidy collection of bric-a-brac. Over the years Esme had siphoned off unwanted bits of furniture from The Lodge barn. There was a chair, a little table, a couple of rugs, a rusty portable barbeque, firelighters, matches, an old saucepan and a row of tins filled with teabags, sugar and digestive biscuits. The walls were festooned with cobwebs. In one corner there was an upturned crate draped with a fading chintz cushion cover. Carefully laid out on top of this makeshift counter sat a selection of Esme’s possessions. Sliding the chair across the floor, Esme sat before the crate and picked up a lace handkerchief with the initials D. L. embroidered in one corner. She wiped her eyes, her tears joining the stains of her mother’s from long ago, marking the linen with crinkly little circles. There was no point in crying; it wouldn’t change anything. Her mother had really done it this time. Esme had forgiven her too often and to have forgotten her at Christmas was unforgivable. She would save up her pocket money and buy a new riding hat herself. Maybe she could take some money from her mother’s purse? It wouldn’t be like stealing because she should have spent the money already on her hat.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: