По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

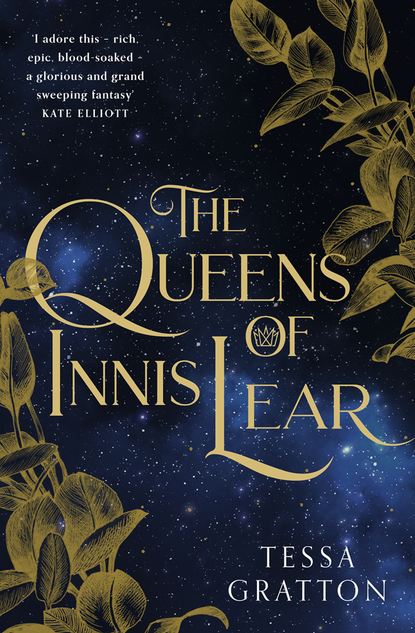

The Queens of Innis Lear

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She paused, telling herself she’d imagined it, and had remained kneeling before the eastern altar. But the language of trees would not spring to her lips easily; Regan’s attention was all for her womb, waiting, hardly able to breathe.

The delicate thread of nausea might’ve been overlooked by one unused to such things. But Regan had been through this before, and so followed the nausea as it turned over into a knot between her hips, then pulled tight.

The princess’s cool brown hands began to tremble. She knew this pain well, and how to hold rigid until it passed.

And pass it did, but not without leaving that ache behind, an echo of itself that radiated down the backs of her thighs and up her spine, hot and cold and hot again.

“No,” Regan hissed, scraping her nails too hard on the stone altar. One cracked, and that pain she welcomed. Her breath caught like a broken necklace, dragging up, up, up, and chattering her teeth. She bared them in rage and forced her breathing into long, slow rolls.

Was it her? Was this failure some greater symptom of the island cracking?

Any beast could be a mother—there were babes in nests and hovels and barnyards. It was only Regan who seemed unable to join them.

When the next cramp caught her, she cried out, shoved away from the altar, and curled tightly over her knees. She whispered to herself that she was healthy and well and most of all strong, as if she could change what happened next by ordering her body to obey her.

A pause in the pain left her panting, but Regan ground her teeth and stood up on her bare feet. Though preferring quite formal attire, even in her husband’s castle, Regan had come to the altars today in only the thinnest red wool dress and no underthings. She’d left her slippers outside the arched gate and untied the ribbons from her wavy brown hair, allowing it to spill past her waist. Hers was the longest, straightest hair of her sisters, and her skin the lightest, though still a very cool brown. There was the most of their father, Lear, in her looks: the shape of his knifelike lips, and flecks of Lear’s blue lightened his daughter’s chestnut eyes.

Regan walked carefully to the ropey old oak tree to pray, her hands on two thick roots. I am as strong as you, she said in the language of trees. I will not break. Help me now, mother, help me. I am strong.

The tree sighed, its bulk shivering so that the high, wide leaves cast dappled shadows about like rain in a storm.

Regan went to the northern altar and cut the back of her wrist with a stone dagger, bleeding into a shallow bowl of wine. Take this blood from me instead, she whispered, pouring the bloody wine over the altar, where north root was etched in the language of trees. The maroon liquid slid into the rough grooves, turning the words dark. Take this, and let me get to my room where my mothers’ milk tonic is, where my husband—

The princess’s voice cut away at the sensation of blood slipping out of her, tickling her inner thighs with dishonest tenderness.

She returned to the grand oak tree on slow legs, sat on the earth between two roots, and slumped over herself. Despair overwhelmed her every thought, as hope and strength dripped out of her on the heels of this treacherous blood.

The sun lowered itself in the sky until only the very crown of the oak was gilded. The courtyard below was a cold mess of shadows and silver twilight. Regan shivered, despite tears hot in her eyes. In these slow hours she allowed herself a grief she would deny if confronted by any but her elder sister. Grief, and shame, and a cord of longing for her mother who died when she was fourteen. Dalat had birthed three healthy girls, had done it as far away from her own land and god and people as a woman could get. And Regan was here among the roots and rocks of her home. She should have been—should have been able.

The earth whispered quiet, harsh sighs; Regan heard the rush of blood in her ears and through the veins of the tree. She saw only the darkness of her own closed eyes, and smelled only the thick, musty scent of her womb blood.

“Regan, are you near?”

It was the sharp voice of her husband. She put her hands on her head and dug her nails in, gripped her hair and tore until it hurt.

His boots crunched through the scattered grasses, over fallen twigs and chunks of stone broken off the walls.

“I’ve been looking for you everywhere, wife,” he said, in a tone more irritable than he usually directed at her. “There’s a summons from your … Regan.” Connley said her name in a hush of horror.

She could not look up at him, even as she sensed him bend beside her, too close, and grasp her shoulders to lift her up off her knees. “Regan,” he said again, all tenderness and tight fear.

Her eyes opened slowly, sticky with half-dried tears, and she allowed him to straighten her. She leaned into him, and suddenly her ankles were cold where air caressed streaks of dark red and brown, left from her long immersion in blood and earth.

“Oh no,” Connley said. “No.”

The daughter of the king drew herself up, for she was empty again now, and without pain. She was cold and hungry and appreciated the temporary bliss of detachment. “I am well, Connley,” she said, using him as a prop to stand. Her toes squished in the bloody earth. Regan shuddered but spoke true:

“It is over.”

Connley stood with her, blood on the knee of his fine trousers, the letter from her father crushed against the oak tree’s root, forgotten. He was a handsome, sun-gilded man, with copper in his short blond hair. His chin was beardless, for he had nothing to hide and charm enough in his smile for a dozen wives. But now Connley had gone sallow and rigid from upset, his smile sheathed. He put his hands on Regan’s face, touched thumbs to old tears just where her skin was the most delicate purple, beneath her eyes. “Regan,” he whispered again, disappointed. Not with her, never with her, but still, that was how it sounded to her ears.

She tore free of him, storming toward the eastern altar that had not been blessed this afternoon. With one bare foot, she shoved and kicked at it, jaw clenched, hands in fists, hair wild and the tips of it tinged with blood. What was wrong with her? In the language of trees, she cried, What is wrong with all of us?

It was her father’s fault. When he’d killed Dalat, he’d killed their entire line.

“Stop, stop!” Connley ordered, grabbing her from behind. He grasped her wrists and crossed them over her chest. He held her tightly, his cheek to her hair. She felt his hard breath blowing past her ear, ragged and unchecked. His chest against her back heaved once, and twice, then his arms jerked tighter before he released his stranglehold, but did not quite let her go. They slumped together.

“I cannot see what’s wrong with me,” Regan said, her head hanging. She turned her hands to hold his. All her hair fell around her face, tangling with their clasped hands. She gazed at the altar, which she had only shifted slightly askew. “I have tried potions and begged the trees; I have done everything that every mother and grandmother of the island would tell me. Three months ago I visited Brona Hartfare and I thought—” She sobbed pure air, letting it out rough and raw. “I thought this time we would catch, we would hold on, but it will never now. My thighs are sticky with the brains of our babe, Connley, and I want to rip out my insides and bury it all here. I am nothing but bones and desperation.”

He unlatched his hands and turned her toward him, gathering her hair in one fist. “This is the only thing that makes you speak in poetry, my heart. If it were not so terrible, I would call it endearing.”

“I must find a way to see inside myself! To find the core of what curses me.”

“It might be a thing wrong with me. More than a mother is required to get a strong child.”

Regan scratched her fingers down the fine scarlet of his jacket, tearing at the wool, the velvet lining the edge. “It is me. You know the stars I was born under; you know my empty fate.” When she said it, her father’s voice echoed in her memory.

“That is your father talking, Regan.”

She reeled back and slapped him for daring to notice. The edge of his high cheek turned pink as he studied her with narrowed, blue-green eyes. Regan knew the look in them: the desire, the scrutiny. She touched his lips and met his gaze. He was a year younger than her, ambitious and lacking kindness, and Regan loved him wildly. Every sign she could read in those damnable stars, every voice in the wind and along the great web of island roots had cried yes when she asked if Connley was for her. But this was her fourth miscarriage in nearly five years of marriage. Plus the one before they’d been married at all.

Connley drew her hair over one shoulder, kissed her finger as it lingered on his bottom lip.

“I don’t know what to do,” the princess said.

“What we always do,” her lover replied. “Come inside and bathe, drink a bit of wine, and fight on. We will achieve what we desire, Regan, make no mistake. Your father’s reign will end, and we will return Innis Lear to glory. We will open the navel wells and invite the trees to sing, and we will be blessed for it. Our children will be the next kings of Innis Lear. I swear it to you, Regan.” Connley turned, his eyes scouring the darkening courtyard. Though Regan did not wish to release him, she did. She stared as he picked his way back to the oak tree and lifted up the letter. It was crumpled now, torn at one corner. He offered it to her.

Regan smoothed the paper between her hands and lifted it to the bare, hanging light of dusk.

Daughter,

Come to the Summer Seat for a Zenith Court, this third noontime after the Throne rises clear, when the moon is full. As the stars describe now, I shall set all my daughters in their places.

Your father and king,

Lear

“Would I could arrive heavy with child,” Regan murmured, touching her belly. Connley put his hand over the top of hers and moved it lower to the bloody stain. He cupped her hand gently around herself.

“We will go heavy with other things,” he said. “Power, wit, righteousness.”

“Love,” she whispered.

“Love,” he repeated, and kissed her mouth.

As Regan returned her husband’s kiss, she thought she heard a whisper from the oak tree: blood, it said, again and again. She could not tell if the tree thanked her for the grave sustenance she’d fed its roots, or offered the word as warning of things to come.

Perhaps, as was often the case with the language of trees, the word held both meanings—and more too unknowable to hear.