По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

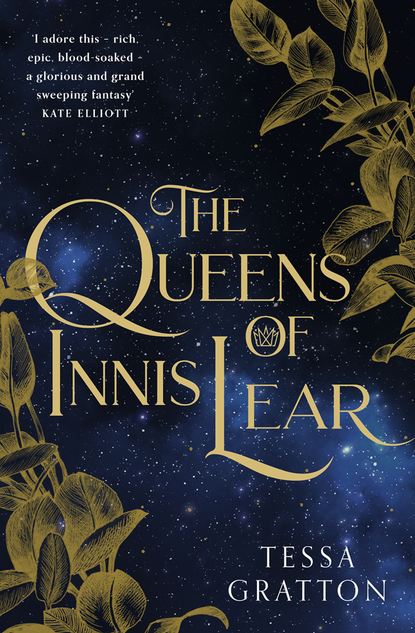

The Queens of Innis Lear

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Astore moved around her to sit in the only chair, a heavy armchair rather like a throne that Gaela brought with her always. He watched her carefully as he drank nearly all his wine. She did not move, waiting. Finally, Astore said, “You’re reckless, setting your men against each other with sharp blades.”

“Those who are harmed in such games are hardly worthy of riding at my side, nor would I be worthy of the crown, to die so easily.”

His grim smile twisted. “I need you alive.”

Gaela sniffed, imagining the release she’d feel if she punched him until that smile broke. But she still needed him, too. The Star of the Consort dominated her birth chart, and to those men of Innis Lear she needed on her council and in her pocket, that meant coming to the throne with a husband. Though Gaela longed for war, she was enough of a strategist to know it was better that the island fight outward, not among themselves. For now, she used Astore, though her sister Regan would always be her true consort. “What does Lear want?”

“He wrote to both of us; to me he still refuses to allow reconstruction on the coastal road.”

“It isn’t in the stars?” she guessed, restraining the roll of her eyes.

“But it is—I commissioned a chart by my own priests. He twists his reasoning around and dismisses what seems to be obvious necessity. Possibly Connley has been whispering in his ear.”

“He hates Connley more than you, usually.” She sank onto the thick arm of the chair and leaned across Astore’s chest for the unopened letter.

Placing his arm just below her elbow in case she needed steadying, but not quite touching her, Astore did not disagree. “I might write to your little sister and ask her for a prophecy regarding the coastal road. Lear has never yet argued with one of hers.”

Gaela drank the rest of her wine and set the cup on the rug before cracking the dark blue wax of Lear’s seal.

Eldest,

Come to the Summer Seat for a Zenith Court, this third noontime after the Throne rises clear, when the moon is full. As the stars describe now, I shall set all my daughters in their places.

Your father and king,

Lear

Grimacing, Gaela dropped the message into Astore’s lap. She touched the tip of her tongue to her front teeth, running it hard against their edges. Then she bit down, stoking the anger that always accompanied her father’s name. Now it partnered with a thrill that hummed under her skin. She knew her place already: beneath the crown of Lear. But did this mean he would finally agree? Finally begin the process of her ascension?

“Is he ready to take off the crown? And will he see finally fit to hand it to you, as is right?” Astore’s hand found her knee, and Gaela stared down at it, hard and unflinching, but her husband only tightened his grip. The three silver rings on his first three fingers flashed: yellow topaz and pink sapphires set bold and bare. They matched Gaela’s thumb ring.

She methodically pried his hand off her knee and met his intense gaze. “I will be the next queen of Innis Lear, husband. Never mistake that.”

“I never have,” he replied. He lifted his hand to grasp her jaw, and Gaela fell still as glass. His fingers pressed hard, daring her to pull away. Instead she pushed nearer, daring him in return to try for a kiss.

Tension strained between them. Astore’s breath flew harsher; he wanted her, violently, and for a moment she saw in his eyes the depth of his fury, a rage usually concealed by a benevolent veneer, that his wife constantly and consistently denied his desire. Gaela did not care that he hated her as often as he loved her, but she did care that his priorities always aligned with her own.

Gaela put her hand on Astore’s throat and squeezed until he released her. She kissed him hard, then, sliding her knee onto his lap until it forced his thighs apart. Scraping her teeth on his bottom lip, she pulled back, not bothering to hide that the only desire she felt now was to wash off the taint of his longing.

“My queen,” the duke of Astore said.

Gaela Lear smiled at his surrender.

THE FOX (#ulink_75a3aeae-5ca7-5e64-9640-7e49627b9e99)

BAN THE FOX arrived at the Summer Seat of Innis Lear for the first time in six years just as he’d left it. Alone.

The sea crashed far below at the base of the cliffs, rough and growling with a hunger Ban had always understood. From this vantage, facing the castle from the sloping village road, he couldn’t see the white-capped waves, just the distant stretch of sky-kissed green water toward the western horizon. The Summer Seat perched on a promontory nearly cut off from the rest of Innis Lear, its own island of black stone and clinging weeds connected only by a narrow bridge of land, one that seemed too delicate to take a man safely across. Ban recalled racing over it as a boy, unconcerned with the nauseating death drop to either side, trusting his own steps and the precariously hammered wooden rail. Here, at the landside, a post stone had been dug into the field and in the language of trees it read: The stars watch your steps.

Ban’s mouth curled into a bitter smile. He placed his first step firmly on the bridge, boots crushing some early seeds and late summer flower petals blown here by the vibrant wind. He crossed, his gloved hand sliding along the oiled-smooth rail.

The wind’s whisperings were rough and harsh, difficult for Ban to tease into words. He needed more practice with the dialect, a turn of the moon to bury himself in the moors and remind himself how the trees spoke here, but he’d only arrived back on Innis Lear two days ago. Ban had made his way to Errigal Keep to find his father gone, summoned here to the Summer Seat, and his brother, Rory, away, settled with the king’s retainers at Dondubhan. After food and a bath, he’d had a horse saddled from his father’s stable. To arrive in time for the Zenith Court, Ban hadn’t had the luxury to ride slowly and reacquaint himself with the stones and roots of Innis Lear, nor they with his blood. The horse was now stabled behind him in Sunton, for horses were not allowed to make the passage on this ancient bridge to the Summer Seat.

At the far end, two soldiers waited with unsharpened halberds. They could use the long axes to nudge any newcomer off the bridge if they chose. When Ban was within five paces, one of them pushed his helmet up off his forehead enough to reveal dark eyes and a straight nose. “Your name, stranger?”

Ban gripped the rail and resisted the urge to settle his right fist on the pommel of the sword sheathed at his belt. “Ban Errigal,” he returned, hating that his access would be determined by his family name, not his deeds.

The soldiers waved him through, stepping back from the brick landing that spread welcomingly off the bridge.

A blast of wind shoved Ban forward, and he nearly stumbled. Using the motion to turn, he asked the guard, “Do you know where I might find the Earl Errigal?”

“In the guest tower.”

Ban nodded his thanks, glancing at the scathing sun. He did not relish this meeting with his father. Errigal traveled to Aremoria every late spring to visit the Alsax cousins and to be Lear’s ambassador. He’d always lavished praise on Ban in front of others, awkwardly labeling his son a bastard at the same time.

Perhaps Ban could eschew the proper order of greeting, and ask instead where the ladies Lear would be this time of day. Six years ago he’d have found Elia with the goats. But it was impossible to imagine she hadn’t shifted her routine since childhood. He had changed; so must she have. Grown tall and bright as a daffodil, or worn and weathered like standing stones.

Ban squashed the thought of her hair and eyes, of her hands covered in green beetles. He suspected most of his memories were sweetened by time and brightened with longing, not accurate to what their relationship had truly been. She, the daughter of the king, and he, the bastard son of an earl, could not have been so close as he remembered. Probably the struggle and weariness of being fostered to a foreign army, the homesickness, the dread, the years of uncertainty, had built her into a shining memory no real girl could live up to. Especially one raised by a man like Lear. In his earliest years at war, Ban had thought of Elia to get himself through fear, but it had been a weakness, like the straw doll a baby clings to against nightmares.

Surely she would disdain him now because of the stars at his birth, just as the king had. If she remembered him at all. One more thing to lay at the feet of Lear.

Ban settled his hand on the pommel of his sword. He’d earned himself his own singular epithet. He was here at the Summer Seat not as a cast-off bastard, but as a man in his own right.

Turning a slow circle, Ban made himself change his eyes, to observe the Seat as the Fox.

Men, women, soldiers, and ladies swarmed in what he guessed was an unusual amount of activity. The castle itself was a fortress of rough black stones quarried centuries ago, when the bridge was less crumbled, less tenuous. It rose in a barbican here, spreading into the first wall, then an inner second wall taller than this first, with three central towers, one built against the inner keep. The king’s family and his retainers could fit inside for weeks, as well as his servants and the animals necessary to live: goats, pigs, poultry. Barracks, laundry, cliff-hanging privies, the yard, the armory, and the towers: Ban remembered it all from childhood. But it was ugly, old and black and asymmetrical. Built over generations instead of with a singular purpose in mind.

The Fox was impressed with how naturally fortified the promontory was, how difficult it would be to attack. But as he studied his environs, the Fox knew it would be easy to starve out. Surround it landside with an enemy camp, and seaside with boats, and it could be held under siege indefinitely with no more than, say, fifty men.

If one could locate the ancient channel through which spring water flowed onto the promontory, the siege would be mercifully brief. Were he the king of this castle, he’d order a fort built landside, to protect the approach, and use the promontory as a final stand only once all other hope had been lost.

Unless, perhaps, there were caves or unseen ways from the cliffs below where food could be brought in—and there must be. But an enemy could poison the water in the channel, instead of stopping it up. The besieged could not drink seawater. Was there a well inside? Not that Ban could recall from his youth, and it was surely less likely now. This place was a siege death trap, though winning such a battle would be symbolic only: if the Seat were under siege, the rest of the kingdom should already have fallen, and so what would the Seat be against all that?

Ban felt a twisted thrill at the idea of the king of Innis Lear having to make such choices. Better yet if his course here led directly to it.

He went along the main path through the open iron gates and into the inner yard where soldiers clustered and the squawking of chickens warred with hearty conversation, with the cries of gulls hunting for dropped food, the crackle of the yard-hearth where a slew of bakers and maids prepared a feast for the evening. Ban’s stomach reacted to the rich smell, but he didn’t stop. He strode quickly toward the inner keep, one hand on the pommel of his sword to balance it against his hip. Ban wondered if he could greet his father (he was fairly certain he remembered which was the guest tower) and then find a place to wash, in order to present himself in a fitter state than this: hair tangled from wind, horse-smelling jacket, worn britches, and muddy boots. He’d dumped his mail and armor in Errigal to make a faster showing astride the horse.

A familiar orange flag caught his attention: the royal insignia of Aremoria.

There was a good king. The sort of soldier who took his turn watching for signal lights all night long, digging his own privy pits and rotting his toes off. Who had suffered alongside his men and took his turn in the slops and at the dangerous front. Morimaros of Aremoria did not make choices based on nothing but prophecy.

Across the yard a maroon pennant flapped: the flag of the kingdom of Burgun. Ullo the Pretty. Also come to court Elia Lear, despite, or maybe because of, being trounced in battle.

Ban wondered what she thought of the two kings.

Beyond the second wall, the smell of people, sweat, and animals was crushing. The lower walls had no slits or windows, nothing to move air, and Ban longed to climb onto the parapets, or into the upper rooms built with cross-breezes in mind, because this was where court spent the months warm enough for it. From the parapets he’d be able to see the island’s trees, at least, if not hear them: the moss and skinny vines growing on this rock had not the will for speaking. Ban made for a stairway cut along the outside of the first, only to freeze at the base when his father appeared in the dark archway above.

Ban waited to be noticed.