По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

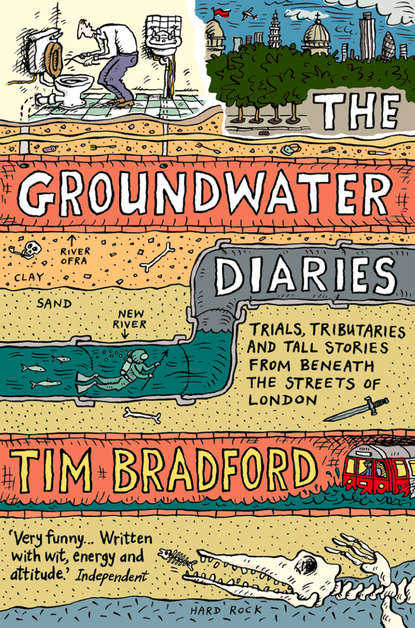

The Groundwater Diaries: Trials, Tributaries and Tall Stories from Beneath the Streets of London

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They’ll make you an epitome of everything that’s wrong.

Do they owe us a living?

Of course they do,

Of course they do.

Do they owe us a living?

Of course they do,

Of course they do.

Do they owe us a living?

OF COURSE THEY FUCKING DO.3

‘Do they owe us a living?’, Crass

Back on Hornsey Road I walk through the tunnel under the mainline railway to the north. The walls have the peeling skin of a decade and a half of pop posters. At the edges I can make out flaking scraps from years ago – Hardcore Uproar and Seal plus multiple layers of old graffiti.

(#ulink_9093b87c-d3d4-5f11-9e3f-a669a6a0982b)

I’ve wandered away from the course of the river. Access is impossible due to the railway lines and the Ashburton Grove light industrial estate, the planned site of Arsenal’s new stadium. There’s a seventies factory development, a taxi car park and another broken car, this one burnt out as well. A big-boned bloke in a shell suit is inspecting it. Was it his? Maybe he was on a stag night and his mates did up his motor for a laugh. The road is a dead end so I walk back and around Drayton Park station with the river valley off to my left under the Ashburton Grove forklift centre – for all your forklift needs. There’s a beautiful big sky that’ll be lost when Arsenal build their new dream stadium. To the right is Highbury Hill, with allotments on the other side of the road banking down to the railway like vineyards, a vision of a different London.

And so into the reclaimed urban landscape of Gillespie Park. It’s an ecology centre developed on old ground near the railway, with different landscape areas and an organic café. I sit down for a while and stare out at the little stone circle and neat marshland pools, surrounded by grassland and meadow in a little urban forest created by local people, and listen to the sounds of thirteen year olds being taught about ‘nature’ by their teacher.

‘Can we catch some tadpoles sir. Goo on.’

‘No, now we’re going to look at the water meadow.’

‘Aww fuckin’ boring.’

The kid sticks his net into the pool anyway and swishes it around, while shouting, ‘Come on, you little bastards.’ The teacher, evidently of the ‘smile benignly and hope the little fucker will go away’ school of discipline, smiles benignly and begins telling the group about the importance of medicinal herbs.

I walk up the track past the ‘wetlands’ and can see Isledon village on the other side of the tracks. You get a sense of how the railway carved through the landscape in the mid-nineteenth century. Even then, when progress was a religion, people would have been aware of the landscape that would be lost:

I am glad there is a sketch of it before the threatened railway comes, which is to cut through Wells’ Row into the garden of Mr I. and go to Hackney. We are all very much amazed at the thought of it, but I fear there is little doubt it will come in that direction.

local girl Elisabeth Hole to her friend Miss Nicols,December 1840

In Gillespie Park it’s hard to discern the real contours of the land because it’s obviously been built up. There’s a little tunnel into the trees, then down a dirt track to a wooden walkway and to the left is marshland. It’s like a riverside. I stop and look across to the little meadow with another stone circle on the left. The rain lets up for a while and I sit down at a bench behind the stone circle with my notebook. Nearby, in the circle itself, sit four dishevelled figures. Two black guys, one old and rasta-ish with a high-pitched Jamaican accent, one young with a little woolly hat and nervy and loud, a tough-looking middle-aged cockney ex-soldier type and a rock-chick blonde in her late forties with leather jacket and strange heavy, jerky make-up. They look battered and hurt and are all talking very loudly, the men trying to get the attention of and impress the woman, as a spliff is passed around and they sip from cans of Tennent’s Super. They must be twenty-first century druids. The younger bloke, whose name is Michael, starts to shout out, ‘Poetry is lovely! Poetry is beautiful! Chelsea will win the league.’ I finish my quick notes and get up to go, as he smiles at me still singing the joys of football and poetry.

‘You’re right about the poetry anyway,’ I say.

‘Do you know any poems?’ he asks. I recite the Spike Milligan one about the water cycle:

There are holes in the sky where the rain gets inThey are ever so small, that’s why rain is thin.

‘Spike is a genius. What a man!’ he yells. ‘We love Spike, Spike understands us!’ and he starts to sing some strange song that I’ve never heard before. Maybe it was the theme tune to the Q series. Then the little Jamaican bloke with a high-pitched singsong accent jabs me in the chest, his sad but friendly eyes open wide, and he smiles.

‘If ya fell off de earth which way would ya fall?’

‘Er, sideways,’ I say, trying to be clever, because it is obviously a trick question.

‘NO ya silly fella. Ya’d fall up. And once ya in space dere is only one way to go anyway and dat’s up. Dere’s only up.’

‘The only way is up!’ sings Michael. ‘Baby, you and meeeeee eeeee.’

‘Whatever happened to her?’ asks the woman.

‘Whatever happened to who?’

‘To Yazz … ’

At this strange turn in the conversation I wave goodbye and walk towards the trees. The little gathering is a bit too similar to the blatherings of my own circle of friends, confirming my suspicion that many of us are only a broken heart and a crate of strong cider away from this kind of life. I can see Arsenal stadium up to the right, looming over the houses. At a little arched entrance, a green door to the secret garden, I come out onto Gillespie Road.

This is the heart of Arsenal territory, where every fortnight in winter a red and white fat-bloke tsunami gathers momentum along Gillespie Road, replica-shirted waddlers dragged into its irrepressible wake from chip shop doorways and pub lounges, as it heads west towards Highbury Stadium. As an organism it is magnificent in its tracksuit-bottomed lard power, each individual walking slowly and thoughtfully in the footsteps of eight decades of Arsenal supporters. Back in the days of silent film, when the Gunners first parachuted into this no-man’s-land vale between Highbury and Finsbury Park from their true home in Woolwich, south London, football fans lived a black-and-white existence and moved from place to place at an astonishing 20 m.p.h., while waving rattles and wearing thick cardboard suits in all weathers. No wonder they were thin. Going to a game was a high-quality cardiovascular workout.

(Then: Come on Arsenal. Play up. Give them what for (hits small child on head with rattle) spiffing lumme stone the crows lord a mercy and God save the King.

Now: Fack in’ kant barrstudd get airt uv itt you wankahh youuurr shiiiitttttt!!)

The source of this vast flow of heavily cholesteroled humanity is the pubs of Blackstock Road – the Arsenal Tavern, the Gunners, the Woodbine, the Bank of Friendship and the Kings Head. Further north are the Blackstock Arms and the Twelve Pins. To the south, the Highbury Barn. The pubs swell with bullfrog stomachs and bladders as lager is swilled in industrial-sized portions.

Walk from the south and there’s a different perspective. People in chinos with City accents jump out of sports cars parked in side streets, couples and larger groups sit in the Italian restaurants of Highbury Park chewing on squid and culture and tactical ideas gleaned from the broadsheets and Serie A. As I mentioned before, the scut line is around my street. Here, outside the Arsenal Fish Bar, which is actually a post-modern twenty-first-century Chinese takeaway, lard-bellied skinheads stuff trays of chips down their throats to soak up the beer. Inside the café, on the walls nearest the counter, there’s a picture of ex-Gunners superstar Nigel Winterburn looking like he’s in a police photo and has been arrested for stealing an unco-ordinated outfit from C&A, which he is wearing (should have destroyed the evidence, Nige).

In the Arsenal museum they have lots of great cut-out figures of many of the players who have long since departed. And a film, with Bob Wilson’s head popping up at the most inopportune moments. He does the voiceover but materializes (bad) magically every time there’s something profound to say, then dematerializes (good) in the style of the Star Trek transporter. Lots of nice old photos, and they make no bones about the fact that they never actually officially won promotion to the top division – in fact they’re even quite proud of the shenanigans and arm twisting that went on. My main question, how Gillespie Road tube was changed to Arsenal, is never answered apart from the comment that the London Electric Railway Company did it after being ‘persuaded’ (tour guide laughs) by Chapman.

It’s my belief that Arsenal were somehow involved in the shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

(#ulink_0bc6a841-5cf8-59fa-9737-9433e85c1a86) and the onset of World War I so they wouldn’t have to spend too long in Division Two. For lo and behold, the first season after the war they got promoted, despite only finishing fifth in the Second Division. How did that happen? It was decided by the powers that be (Royalty, Government, Masons, Arsenal) to expand the First Division following the end of World War I in an attempt to stave off proletarian revolution by giving them more football. By coincidence, Tottenham finished in the bottom three of Division One that year, yet were still relegated.

I dive into the Arsenal Tavern on Blackstock Road for a quick pint of Guinness because it’s only £1.60 during the day and I weigh up whether to ask the landlady about history but she is slumbering near the side door, arms like hams, chins on gargantuan bosoms, so I sit at the bar and chat to a gentleman called Dublin Peter, Cork Johnny, actually no I think it was Mullingar Mick, who anyway I’ve seen and talked to in here before and I notice that everyone is facing east. There are about twelve people in the pub – stare at pint sip stare at pint stare at wall stare at pint sip stare at pint stare at wall and repeat until need piss. The pub was called the New Sluice in the nineteenth century and I imagine they must have documents and photos of the pub back then.

The back room of the Arsenal Tavern is the exact point at which the boarded river crossed over Hackney Brook. I stand there for a few moments drinking and breathing hard, waiting for inspiration or some kind of sign. Peter Johnny Mick then appears again and starts explaining to me why Niall Quinn is still so effective as a front man for Sunderland: ‘He’s got mobility. Mobility, I tell you. He has the mobility of a smaller man. Have you seen how he can turn in the box?’

I walk along an alleyway past a building site where the crushed remains of a tower block lie in mesh-covered cubes like Rice Krispie honey cakes. Nearby is a weeping willow, a nice riverside touch. I eventually come out at the not very aptly named Green Lanes then cross through the northern end of Clissold Park about 200 yards from the New River walk, by the ponds – the brook ran alongside them. It’s an enchanted place, with birds and mad people sitting on the benches. For a brief moment, I imagine I am back a couple of hundred years. Through the gate and over Queen Elizabeth’s Walk.

(#ulink_8505ef96-a773-514c-b2c5-a8e7a1e9b1af) Then along Grazebrook Road, where sheep, I suppose, used to, er, graze next to the brook. Then the land rises up to the right. And left. There’s a school in the way so I go up to Church Street, which is full of young well-spoken mums, old leathery Irishmen dodging into the dark haven of the Auld Shillelagh, unshaven blokes in hooded tops sitting on the pavement asking for spare change, estate agents crammed with upwardly mobile families fecund with dosh or young couples looking longingly at places they can’t afford, skinny blokes with beards on bikes, kids, lots of kids, kids in prams, kids running, kids in backpacks, kids with ice creams, kids playing football, kids coming out of every doorway, Jewish guys with seventeenth-century Lithuanian suits, young lads with thick specs and thin ringlets, the odd big African in traditional dress, tired-eyed socialists and anarchists drinking in big, dirty old pubs and still dreaming of the revolution.

Turning into Abney Park Cemetery, I walk in a loop around its perimeter, past the grave of Salvation Army founder William Booth. It’s quiet and boggy, with lots of standing water and a strange atmosphere like a temperature shift or pressure change. Or something else … ghostly legions of Salvation Army brass bands emitting the spittle from their instruments. Branches curling down over old weathered stone, graves half buried in turf and moss, some with fresh flowers, which is strange as these graves are all well over 100 years old. I wade through big puddles as the track pretty much follows the course of the brook along the cemetery’s northern boundary. My beautiful new trainers keep slipping into the water and I fear I’ll be pulled down to an underworld by the grasping corpse-hands of the shaven-headed vegan N16 dead. The track ends at the main entrance on Stoke Newington High Street.

Just down the road is the Pub Formerly Known As Three Crowns, so called because James I (and VI) apparently stopped for a pint there when he first entered London and united the thrones of England, Scotland and Wales for the first time. Maybe he had the small town boy’s mentality and thought that Stoke Newington was London (‘Och, ut’s on’y gorrt threee pubs!’) In those days Stokey was pretty much the edge of London. Up until that time the Three Crowns had been called the Cock and Harp, a grand fifteenth-century pub which was knocked down in the mid-nineteenth century just to be replaced by a bland Victorian version. When I first used to come to N16 the three nations had become Ireland, the West Indies and Hardcore Cockney, and the age limit was sixty-five and over. Then it was the Samuel Beckett (Beckett wasn’t from bloody Stoke Newington). Now it’s called Bar Lorca (and neither did bloody Lorca. Bloody). How unutterably sad is that? (Puts on cardigan and lights pipe then walks off in a huff). There should be. A law against. That kind. Of. Thing.

I continue towards Hackney, with the common on the right. This used to be called Cockhanger Green, suggesting that Stoke Newington was a sort of Middle Ages brothel Centre Parcs, until someone, most likely a Victorian do-gooder, decided to change the name to the rather less exciting Stoke Newington Common. There used to be an exhibit timeline at the Museum of London showing a Neolithic dinner party. A nineteenth-century archaeological dig had unearthed evidence of London’s earliest Stone Age settlers right here next to the Hackney Brook. The exhibit showed what looked like some naked hippies in a clearing holding twigs, and barbecuing some meat. These days they’d be chased off by a council employee or more likely a drug dealer. I buy a sandwich and wander onto the common then sit down to finish my snack, wondering if any evidence of my meal will appear in some museum 3,000 years hence (‘And here we have artefacts from the time of the Chicken People … ’).

At the junction with Rectory Road ‘Christ is risen’ graffiti is on a wall. A gang hangs about on the street corner, just down from Good Time Ice Cream, typical of gangs around here in that they are all around eleven years old.