По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

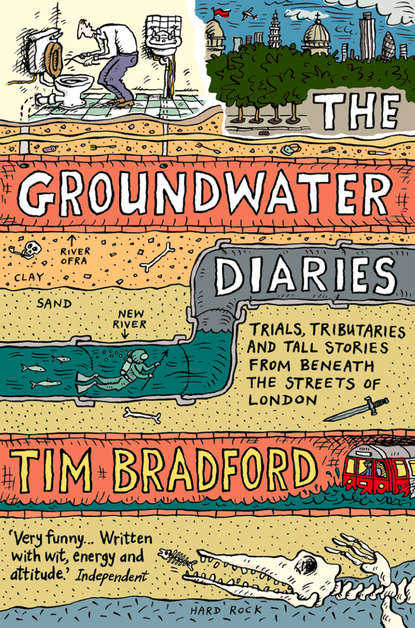

The Groundwater Diaries: Trials, Tributaries and Tall Stories from Beneath the Streets of London

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A tall black geezer strolls up to me and cocks his head to one side.

‘Aabadadddop?’

‘What?’

‘Aabbadabbadop?’

‘What did you say?’

‘Are you an undercover cop?’

‘Argh?’

‘An undercover cop, man? Talkin’ into that tape recorder. What you doin’?’

I spend about five minutes explaining to him about the buried rivers, in my special ‘interesting’ researcher voice, showing him the Hackney Brook drawn into my A to Z and how the settlements grew up around the stream. His eyes start to glaze over and he makes his excuses and speeds off towards Stoke Newington.

At Hackney Downs I can see the slope of the shallow river valley with an impressive line of trees, like an old elm avenue, except they can’t be elms because they’re all dead. At this point I should say what kind of trees they are, being a country boy, but fuck me if I can remember. I used to be able to tell in autumn by looking at the seeds.

At the Hackney Archive there are some old illustrations of Hackney in which the river looks very pretty and rustic as it winds its way past various countryish scenes and one of the Hackney Downs in the late eighteenth century, with a little Lord Fauntleroy type looking down into a babbling (or in Hackney these days it would be ‘chattering’) crystal stream. Behind him, where now there would be muggers, dead TVs, piss-stained tower blocks and junkyards, are bushes, shrubs, trees and general countryside.

Benjamin Clarke, writing 120 years ago, lamented how much it had changed in the previous 150 years and had it on good authority that in the 1740s ‘the stream [“purling and crystal”] was quite open to view, trickled sweetly and full clearly across the road in dry weather but rapidly changed to a deep and furious torrent when storms along the western heights of Highgate and Hampstead poured down their flood waters’.

A few people are hanging out in the Downs but it’s not a real beauty spot, more an old common. A battered train clatters past along the embankment to the right. Along cobbled Andre Street and its railway arches with garages, taxis, banging, welding, industrial city smell of petrol and chemicals, and those urban standing-blokes who never seem to have anything to do. And, of course, smashed cars and engine parts. People doing business, chatting, negotiating, and almost medieval noise among the cobbles. Are you into cars? If not what are you doing down here? We all love cars. Water drips along the cobbles. One day all this will be really shite coffee bars. I make it to the end of the street without buying a car then turn left past the Pembury Tavern – alas, not open any more.

Here, the Victorian stuff blends with spoiled tower blocks/failed high-density housing projects, burned-out cars piled high behind wire fences; swirling purple, shaved-head speccy blokes jogging with three-wheeler prams; shaven-headed bomber-jacketed blokes pulled along by two or three heavily muscled dogs, nineteenth-century schools refurbished for urban pioneers with lots of capital. Hackney used to be shitty, now it’s not so shitty (Tourist sign: ‘Welcome to “Not As Shitty As It Used To Be” Country!’) The brook in central Hackney was culverted in 1859–60. In his book, Benjamin Clarke visits the old church and finds a ducking stool in the tower which used to be near here and where they’d give scolds (women with opinions) the dip treatment. A bloke is following me laughing madly and loudly, then runs across the road into Doreen’s pet shop, no doubt to buy a budgerigar for his lunch.

I head up towards Tesco, built on the site of old watercress beds – I reckon the stream goes right underneath their booze section. I hang around near the liqueurs for a while, checking the emergency exit, when the alarm goes off so I nip around the vegetable section and out by another door. Onto Morning Lane now, which follows the line of the river. There used to be a mill for silk works here and the Woolpack Brewery using Hackney Brook water. I love Benjamin Clarke’s idea that this is a River of Beer. I wonder how easy it would be to turn a stream into beer. Just add massive amounts of hops, malt, barley and yeast, I suppose. Further down there used to be a Prussian blue factory. Lots of big blond lads with moustaches singin’ ‘bout how their woman gone left them ja and ’cos the trains are so damn efficient she’ll be miles away by now. Woke up this morning etc., etc.’ Oh, blue factory, that’s ink, right? Now it’s heavy traffic, cars, white vans, trucks, housing estates.

Large swathes of this part of Hackney must have been flattened by bombs in the Second World War. Or by the progressive council madmen who hated the elitism of nice houses and squares. Past Wells Street and little funky shops where the tributary marked ‘Hackney Brook’ on my map used to flow. Reggae blasts out from a shop – Rivers of Dub. People shouting, radios blaring, big arguments. At the end of Wick Road two guys in tracksuit trousers (or sports slacks) are giving hell to each other and pointing at each other’s chests. Up above is the sleek black hornet shape of a helicopter, watching. On the other side of these flats, to the north, are the Hackney marshes.

Two pubs here, one a cute compact place, dark green and yellow Prince Edward, not the not-gay TV production guy but the Prince of Wales who became Edward VII, the fat bloke with a goatee who liked shagging actresses. I have an idea for stickers with a river logo and pint glass plus a thumbs up sign, like an Egon Ronay guide thing, that landlords of pubs along the routes of rivers could put on their front doors.

Benjamin Clarke wrote that when he was young that ‘the popular name for the area around Wick Lane and beyond was “Bay” or “Botany”, so nicknamed because of the many questionable characters that sought asylum in the wick, and were ofttimes not only candidates for, but eventually contrived to secure transportation to Botany Bay itself’.

More flats here, cubist and Cubitt mixed together. Then at the junction to Brook Road the roads rise up each side from the river valley. I keep straight on. There’s a new Peabody Trust building site, announced by their little logo, which is two blue squiggly lines, like waves – maybe they only build on top of buried rivers. From Victoria Park, on a slight hill where the river once skirted round the north-east corner, I can see tower blocks in the distance of different shapes and sizes.

Back out and down into the river valley into the heart of the Wick under some rough-looking dual carriageways, past a lime green lap dancers’ pub on the left. I turn right underneath both roads of the A12 Eastcross route, onto the Eastway. A little old building says ‘Independent Order of Mechanics lodge no. 21, 1976’. Their sign is a sort of Masonic eye with lines coming out from the centre. I pass the Victoria, an old Whitbread pub seemingly left high and dry by the road building, and St Augustine’s Catholic Church, which hosts Eastway Karate Club. Then a beautiful thirties swimming pool in the urban Brit Aztec style. I look along Hackney Cut, a waterway made for the mills of the district so the Lea could still be navigable, as it stretched down further into the East End.

Now I am in Wick Village with its CCTV and sheltered housing. It’s pretty dead, like the end of the line, a real backwater – dead cars resting on piles of tyres then a graveyard with hundreds of cars piled up. I climb up a footbridge to take a look around. It’s still ugly from there, except I can see more of it. Lots of dirt in the air, windswept, everything is coated in it, blasted and bleached, grit in my eyes. Someone has dropped a big TV from a height and it lies in pieces by the stairs – perhaps in protest at the death of the Nine O’clock News. Great piles of skips here like children’s toys, and lots of traffic. I cross over the Stratford Union Canal lock and to the Courage Brewery, where an army of John Smiths bitter kegs wait to do their duty.

A couple of old people dawdle up to me and I ask them about what they know about Hackney Brook.

Responses of local old people when you ask them about an underground river

1. Outright lying

2. Wants to unburden soul

3. Does rubbing thing with ear suggesting they’re contacting some secret organization

4. Doesn’t understand me

5. Idea of underground river makes them want to urinate – ‘You are my best friend!’ etc.

There’s a plaque for the Bow Heritage Trail and the London Outfall Sewer walk. Part of London’s main drainage system constructed in the mid-nineteenth century by Sir Joseph Bazalgette. I can smell the shit. It’s a shitty sky as well. But at last I can hear birdsong. There are scrub trees, wildflowers, grasshoppers, daisies and cans of strong cider.

Finally I am at the point where the newer Lea Navigation cut meets the old River Lea/Lee. The name is of Celtic origin, from lug, meaning ‘bright or light’. Or dedicated to the god Lugh (Lugus). There are two locks here. This is the end of my walk, although the path continues to Stratford marsh. Two big pipes appear, on their way down to a shit filter centre (technical term) somewhere out east. Maybe there is poo in one and wee in the other. I go down some steps to have a closer look at the river. The sewer is in a big metal culvert under the path. There’s a small sluice gate on the other side, also an old wooden dock. Water rushes out a bit further up, and I’m happy. Maybe that is the Hackney Brook, maybe it isn’t. It’s good enough for me.

To the left is Ford Lock near Daltons peanut factory, on the right the placid winding waters of the old Lea. I cross over the locks and am blasted by the smell of roast potato and cabbage. It’s deserted, like an old film set.

My online dream doctor Mike’s online dream interpretation arrives:

Hello Tim!

A very interesting dream indeed! It looks to me more like it is set in a future setting than in the past, and it sounds like a very beautiful place! (!) Water is symbolic of change, and it seems that your dream makes quite an artwork out of change. Walking over the deep crevices in the ground is symbolic of passing over problems in life successfully. If you were not passing over them successfully you’ll be falling into or stumbling on the crevices. The glass over it covered in little red dots sounds to be very symbolic of health issues.

The flying water sounds to be very symbolic of the turbulent future, but the way you handle yourself and your feelings about this dream make it sound like everything will be fine. It sounds like this dream is predicting some hard times ahead, but you are able to overcome them and continue along a path.

I certainly hope this helped you, there really wasn’t a whole lot to go on. If I may be of further assistance please feel free to write.

Sincerely,

Mike

ps: This is not to be considered medical or psychological advice because I am not a doctor or psychologist. I offer this as my opinion and should be evaluated with this in mind.

I phoned up Arsenal F.C. and got through to the club historian, who denied any knowledge of the underground river (he would) but he did tell me that the site was purchased from the St John Ecclesiastical college. The Knights of St John, the Knights Hospitallers, acquired the Templars’ land when they were outlawed in the early fourteenth-century. Canonbury Tower, whose lands stretched down to St John’s Priory, Clerkenwell, has Templarism for its foundations, and a cell in Hertfordshire, on or near, the old estate of Robert de Gorham, was connected with the Order of St John established in Islington. All of Hackney was owned by the Templars, and large parts of Islington. Does this mean anything? Is Highbury Stadium a Masonic stronghold?

The historian skilfully rebuffed my information-gathering technique which, I’ll be honest, consisted of me saying, ‘Blah blah underground rivers blah – so, are you a Mason?’ in a Jeremy Paxman voice. He laughed and made a joke of it. Then I heard a very audible click, which could have been the gun he was about to shoot himself with. Or the sound of secret service bugging equipment. MI5 could be listening in. Or is it my hurdling knee playing up again?

Various people have attempted to explain Occam’s Razor to me. Basically, if there are two explanations for something, you should choose the simplest.

Choice 1: The land near reclaimed rivers was cheap and was bought up by football clubs.

Choice 2: Something to do with mysticism and Masonry, paganism, choosing a river site and picking up on power vibe of ancient druids for occult football purposes.

Hmm. A lesser-known theory is Occam’s Shaving Brush, in which you coat everything with a thin veneer of absurdity and then you can’t see the chin for the stubble. As it were. By burying the streams they – the Victorian sewer maker, brick manufacturers, builders, football club chairmen, the Masons, Edward VII – were burying the last vestiges of the scared goddess worshipping holy springs. It was violent and anti-female, defiling London. No, I meant sacred goddess.

‘What have you got to say to that then?’ I asked the Arsenal historian.

He’d hung up.

More religious people are starting to turn up at my door. It’s the end times, they say. They are joined by an ever-growing band of needy folk who just want something. Yugoslavian immigrants who can only say ‘Yugoslavia’ and ‘hungry’, Childline charity workers, Woodland Trust, gas board people wanting to sell us electricity, electricity board people wanting to sell us gas, people from Virgin wanting to sell us electricity, gas, financial services and some of the thousands of copies of Tubular Bells by Mike Oldfield that they’ve still got piled up in an underground warehouse in the sticks, homeless people trying to sell us kitchen cleaning gear, cancer charity people, environmental groups. One day I opened the door and there was a chicken on the floor outside. It must be an omen. Actually it was a half-eaten piece of KFC with a few chips left behind as well. An urban trash culture post-modern voodoo juju hex. Without a doubt.

Film idea – The Herbert Chapman Story

It’s a mixture of Foucault’s Pendulum, Escape to Victory and The Third Man. Takes over struggling Arsenal and gets in with the Masons to utilize the power of Hackney Brook. Have a spring. Players drink magical waters.