По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

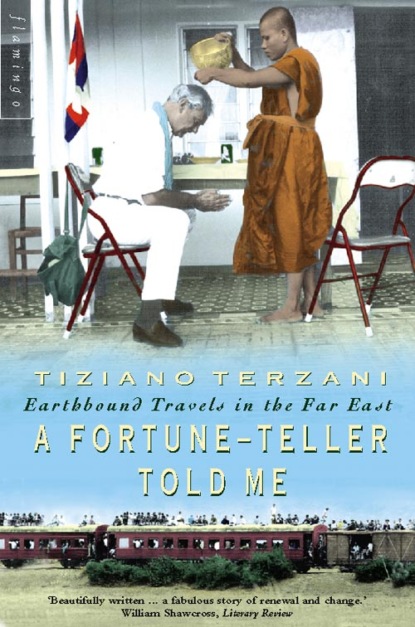

A Fortune-Teller Told Me: Earthbound Travels in the Far East

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But now I was facing a difficult year. I had assumed that even if I could move only very slowly, I would be able to get around by boat. I could not have been more wrong.

Bangkok is a port: hundreds of ships dock there every day, and several times a week the local newspapers publish a thick supplement listing the names and destinations of all the vessels and the times at which they load cargo. We began telephoning around for information about sailings to the Philippines, Vietnam, Hong Kong and Singapore. We may as well have been asking for the moon. I talked with chief clerks, chairmen and managing directors. No use. The politest would say, ‘No, not us. But try another line.’ Or, ‘Yes, we used to carry passengers, but now…’ Impossible. Ships no longer transport anything but goods, preferably sealed in containers which are loaded and unloaded automatically by computer-operated cranes.

To stave off the temptation to give up the whole project I began telling everyone about the Hong Kong fortune-teller and my decision not to fly for a year. This reinforced my commitment, but above all I attracted the sympathy of various Thai friends who suddenly felt ‘understood’. The fact that I had taken a Chinese fortune-teller’s prophecy seriously meant that I had entered into their logic, that I had accepted the culture of Asia. This flattered them, and they declared their willingness to help me, even if only with suggestions and advice. One of the most commonly repeated was: ‘Don’t worry. Try to acquire some merits!’

The underlying idea of acquiring merits is that fate is not ineluctable: a fortune-teller’s predictions must be taken as a warning, or as indicating a tendency, but never as a sentence without appeal. Suppose a fortune-teller sees that you are about to fall gravely ill? Or that someone in your family will soon die? No need to despair. Make offerings in a temple, help an unfortunate, free some caged animals, adopt an orphan, pay for the construction of a stupa or donate a coffin to a poor man, and you will deflect what is otherwise coming for you. Obviously one must be guided by a professional in the choice of the quality, quantity and object of the merits to be acquired, but having done this, one’s destiny has to be examined anew, or rather, it is returned to the hands of the person concerned. Fate is negotiable; you can always come to an agreement with heaven.

Despite all the advice I was given, it was difficult to get an answer to the simple question: ‘Who is the best fortune-teller in Bangkok?’ I had the impression that everyone wanted to keep his favourite to himself. And then too, they are all convinced that the best fortune-tellers are to be found not among themselves but somewhere else. The Thais say the best are in Cambodia, the Cambodians say India, the Chinese that nobody can equal the Mongols, the Mongols believe only in the Tibetans, and so on. It is as if each one, conscious of the relativity that surrounds him, wants to preserve the hope that the absolute exists elsewhere. ‘Ah, if only I could go to that fortune-teller in Ulan Bator!’ a Javanese will say, thus keeping alive the hope that in some other place the key to his happiness can surely be found.

My case was simpler: I was in Bangkok and I wanted to see a fortune-teller there. I wanted to begin my flightless year by reconfirming my fate, by having my future read again. After all, since my encounter with the Hong Kong fortune-teller I had consulted none other.

Since none of my Thai acquaintances was able to recommend a fortune-teller, my friend Sulak Sivaraksa came to mind. He is Thailand’s leading philosopher, twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. A convinced Buddhist, he has been a persistent critic of the way his country is abandoning its traditions, and he never misses a chance of attacking those he believes have strayed from the traditional Buddhist path. The Thai establishment does not care for him, and because of his outspokenness he has been accused of lèse-majesté, a crime that no longer exists elsewhere, and has spent some time in prison. The last time they arrested him I went to see his wife, thinking she would be distraught. Not at all! She had consulted a fortune-teller who had assured her that in a few days Sulak would be released. That is just what happened: the fellow had named the day and the hour. I decided to consult him.

I knew where he lived, and that he was blind. I needed an interpreter, but I did not want to take my secretary or anyone who knew anything about me: he or she might, even if unconsciously, give the fortune-teller a clue as to my trade or my family. So I telephoned an agency that provides secretaries for visiting businessmen. Pretending to be a guest at the Oriental Hotel, I made an appointment to meet my escort in the hotel lobby. The woman who arrived was about fifty, plump, with big glasses. She was delighted at the idea of not having to translate clauses of contracts and conversations about buying and selling.

The fortune-teller lived in the heart of Chinatown, and the Oriental Hotel’s cream-coloured limousine, with a driver in white gold-braided livery, crept at a snail’s pace into the marvellous, chaotic Vorachak quarter which is still one of the noisiest and liveliest parts of Bangkok – still unchanged, thank God, with its thousands of shops selling hardware, pumps, curtains, nails, coffins, sweets; with its myriad smells of incense wafting from little altars at the back of every hole in the wall, or balsam from the pharmacies; with the usual teeming crowds of overseas Chinese in their black shorts, immutable with white undershirts pulled up over their bellies, as if to air the navel and to stimulate the qi – the vital force – which, according to them, has its true centre there.

The fortune-teller lived at the far end of a tangle of little streets reachable only by foot. Finally we found his house. But it was not a house, exactly: through a big iron grille that opened on to the street we entered a large room that doubled as shop and home, where goods and gods cohabited. On one side, among the sacks of rice, was an old iron desk. Behind it, on a cane chair, was a blind man. More perching than sitting, he was massaging his feet, as the Chinese do, convinced that the bodily organs, from the heart to the lungs, the intestines to the liver, are controlled from there; it is enough to know the right points to touch. His eyes were blank. Where the pupils should have been were white spots that seemed always turned skywards. On the desk was a small teapot, a dish of tangerines – a symbol of prosperity – and an empty turtle-shell. The room was filled with a strong smell of incense from a large altar in one corner, full of statuettes made of gilded wood and representing gods and ancestors, the dead not as they were in life, but as they would have liked to have been. This is a curious tradition among the southern Chinese. An uncle failed the Imperial examination? Never mind: after death he is represented as a mandarin. Another had dreamed of being a policeman? After death he appears on the ancestral altar in uniform, with a rifle slung over his shoulder. Many of the fortune-teller’s statuettes held raised swords, as if to protect him in his blindness. An old woman in green silk pyjamas, perhaps his wife, had just finished eating at a round table. She put wicker covers on the pots with the remains of her meal and sat down on a stool at the sink and began washing up.

Slowly, as if he did not want to hurry our relationship, the blind man began whispering something. My assistant translated. It was the usual question, to which I gave the usual reply: ‘I was born in Florence, Italy, on 14 September 1938, at about eight in the evening.’

He seemed satisfied, and began performing some strange calculations with his fingers in the air. His sightless eyes, still raised to heaven, brightened as if he had a great secret with which to capture my attention. His lips whispered a sort of nonsense rhyme, but he said nothing intelligible. A Chinese girl in white pyjamas ran in, handed something to his wife and dashed off, first joining her hands over her bosom in salutation to all the impassive ones on the altar. An old clock on the wall ticked for long minutes. I had the impression that the blind man was searching for something in his memory, and had found it.

At long last his mouth opened. ‘The day you were born was a Wednesday!’ he announced, as if he expected to surprise me. (Right. Bravo! A few years ago he might have impressed many people with that calculation, done entirely by memory. Now it seemed much less impressive. My computer does the same thing in a few seconds.) His satisfaction was touching, but I was disappointed and my interest flagged. I listened to him absent-mindedly. ‘You have a good life, a healthy body and a lively mind, but a very bad character,’ he said. ‘You are capable of great anger, but you are also able to calm down quickly.’ Generalities, likely to be true for anyone sitting before him, I thought. ‘Your mind is never still, you are always thinking about something, which is not good. You are very generous to others.’ Again, true for almost anyone, I told myself.

I had placed a small tape recorder on the table, and took notes as well, but I suspected I was wasting my time. Then I heard the woman translate: ‘When you were a child you were very ill, and if your parents had not given you away to another family you would not have survived.’ My curiosity revived: true, as a small child I was not very healthy. We were poor, it was wartime and we had little to eat; I had lung trouble, anaemia, swollen glands. ‘From the age of seven to twelve you did well at school, but you were often ill and you moved house. From seventeen to twenty-seven you had to study and work at the same time. You have a very good brain, capable of solving various problems, and now you have no worries because you studied engineering. From the age of twenty-four to twenty-nine you went through the most unhappy period of your life. Then everything went better.’

It is true that as a child I was often ill, but not that I began working at seventeen. It is not true that we moved house, but the years between twenty-four and twenty-nine were the most unhappy of my life: I had a job with Olivetti, and thought of nothing but getting away, but did not know how. As for engineering, I studied law.

I was not impressed: it looked like a typical case, where the fortune-teller’s pronouncements have a fifty-fifty chance of being true. My mind wandered. I looked at his hands, which were caressing the turtle-shell on the desk. I heard his continuous whispered calculations, like a computer sifting its memory. Obviously he was mentally shuffling cards. But perhaps his real strength was instinct. Being blind, not distracted by the sight of all the things that distracted me, perhaps he was able to concentrate, to sense the person he had before him. Perhaps his instinct told him that my attention was wandering, because he suddenly broke off the singsong recital.

‘I’ve bad news for you,’ he said. For an instant I was worried. Was he going to warn me about flying? ‘You’ll never be rich. You’ll always have enough money to live, but never will you become rich. That is certain,’ he declared.

I almost laughed. Here we were, in the middle of the Chinese city where everyone’s dream is to become rich, where the greatest curse is just what the fortune-teller had told me. For the people here it really would be bad news, but not for me: becoming rich has never been my aim.

Well then, what would interest me? I asked myself, continuing my silent mental dialogue with the blind man. If I do not want to be rich, what would I like to be? The answer had just taken shape in my head when it came to me from him, still reading his invisible computer. ‘Famous. Yes. You’ll never become rich, but between the ages of fifty-seven and sixty-two you will become famous.’

‘But how?’ I asked instinctively, this time aloud.

The translation had hardly reached him when he lifted his hands and, with a widening smile on his lips, began tapping an imaginary typewriter in mid-air. ‘By writing!’

Extraordinary! The blind man could of course guess that anyone sitting before him would like to be famous, but what gave him the idea that I might do so by writing? Why not by starring in a film, say? Had I perhaps told him? Told him mentally, in no actual language – there was none we had in common – but in that language of gestures comprehensible to anyone who could…see?

Unconsciously, internally, at the very moment when I asked, ‘But how?’ I answered the question and mentally made the gesture of a hand that wrote. Could it be that the blind man ‘read’ this gesture and immediately repeated it with his hands? Is there any other explanation of this brief sequence?

He felt that he had regained my attention, and continued. ‘Until the age of seventy-two you’ll have a good life. After seventy-three you’ll have to rest, and you’ll reach the age of seventy-eight. From now on never try your hand at any business dealings or you’ll lose every penny. If you want to start something new, if you want to live in another country, you must absolutely do it next year.’

Business is something I have never thought about. As for changing countries, I knew I wanted to go and live in India, but definitely not before May 1995, when my contract with Der Spiegel and the lease on the Turtle House were due to expire. And then? It would depend on various circumstances if I could then move. To go next year was impossible, in any case.

‘Be careful; this year isn’t good for your health,’ said the blind man. Then he stopped and did some more calculations with his fingers in the air. ‘No, no, the worst is over. You were through with all that was bad at the beginning of September of last year.’

At this point it seemed only right to let him know why I had come to him, and to tell him about the prophecy of the Hong Kong fortune-teller. The blind man burst out laughing, and said, ‘No, definitely not. The dangerous year was 1991; you did then indeed risk death in a plane.’ He was not mistaken. I shuddered at the memory of all the ghastly planes in which I had flown that summer of 1991 in the Soviet Union, when I was working on my book Goodnight, Mister Lenin.

For a moment I had a sense of disappointment. Perhaps it was only because he knew I was firm in my resolve not to fly that he saw no danger in the future. As I told myself this, I realized how readily the mind will perform any somersault to rationalize what suits it.

We thanked the man, paid, and left. In the little square we found the limousine with the driver in his fine white uniform. ‘Well?’ the woman asked me. I did not know what to say. The strangest thing the blind man had told me was that as a child my real parents had given me to another family, and that only thanks to this had 1 survived. What a risk he took in saying such a thing! In the vast majority of cases it cannot be true, as it was not true in mine. Or perhaps it was? The Oriental Hotel’s car inched slowly through the traffic; my thoughts flew rapidly and delightfully in every direction.

There can be no doubt that I am my mother’s son. Where else would I have got this potato nose, which has re-emerged identically in my daughter? Yet it is equally true that in a certain sense I have never belonged to the family I grew up in. I felt this from an early age, and my relatives recognized it too, jokingly saying to my father: ‘But that one, where did you ever dig him out from?’

The blind man had got the facts wrong, but he had hit on something profoundly true. One only had to interpret, to focus on that part of us that goes beyond our physical being, and ask where it comes from. In my case it does indeed come from ‘another family’, that is to say from another source than the genes that determine the shape of my nose, my eyes, and even certain gestures which now, the older I grow, I recognize more and more as those of my paternal grandfather.

In the tenor of my parents’ ways there was not so much as a germ of the life I have lived up till now. Both of them came from poor, magnificently simple people. Calm people, close to the earth, chiefly concerned with survival – never restless or adventurous, never looking for novelty as I have always done since childhood. On my mother’s side they were peasants who had always worked other people’s land; on my father’s side, stonecutters in a quarry that is still called by their name. For centuries the Terzanis have chiselled the paving stones of Florence, and – it was said – those of the Palazzo Pitti. Nobody in either family had ever gone regularly to school, and my mother and father’s generation was the first that had learned, barely, to read and write.

Where then did I get my longing to see the world, my fetish for printed paper, my love of books, and above all that burning desire to leave Florence, to travel, to go to the ends of the earth? Where did I get this yearning for always being somewhere else? Certainly not from my parents, with their deep roots in the city where they were born and grew up, which they had left only once, for their honeymoon in Prato – ten miles from the duomo.

Among all my relatives there was not one to whom I could look for inspiration, to whom I could turn for advice. The only ones I felt indebted to were my father and mother, who I saw literally go without food to allow me to study after primary school. What my father earned never lasted to the end of the month, and I well remember how sometimes, holding my mother’s hand and trying not to be seen by anyone who knew us, I would go with her to the pawnbroker in the Via Palazzuolo with a linen sheet from her trousseau. Even the money for a notebook was a worry, and my first long trousers – new corduroy ones, good for summer and winter, indispensable for secondary school – were bought by instalments. Every month we would go to the shop to hand over the amount due. It is hard to imagine today, but the pleasure of putting on those trousers is one I have never felt again with any other garment, not even those made to measure for me in Peking by Mao’s own tailor.

As I grew up I had a great affection for my family and its history, but I never felt any real affinity for them – as if I really had been put there by accident. My relatives were irritated by the fact that I studied and did not start working at a very young age, as they had all done. A brother of my father’s, who dropped in every evening before dinner, used to say: ‘What’s he done today, the layabout?’ Then he would trot out the wisecrack that so offended my mother: ‘If he carries on like this he’ll go farther than Annibale!’ Annibale was a cousin, another Terzani, who had gone far indeed. Since boyhood he had worked as a city street cleaner, walking the tram tracks with a spade and rake to clear away the horse droppings.

Why did I practically flee from home when I was fifteen, to go and wash dishes all over Europe? Why, when I arrived in Asia, did I feel so much at home that I stayed there? Why does the heat of the tropics not tire me? Why do I sit cross-legged without discomfort? Is it the charm of the exotic? The wish to get as far away as possible from the poverty-stricken world of my childhood? Perhaps. Or perhaps the blind man was right, if he meant that something in me – not my body, which I certainly got from my parents, but something else – came from another source, that brought with it a baggage of old yearnings and homesickness for latitudes known to me in some life before this one.

Slumped in the back seat of the Oriental Hotel’s car, I let these thoughts whirl around in my head, and amused myself by chasing them as if they were not mine. Could it be that I believed in reincarnation? I had never thought seriously about it. But why not? Why not imagine life as a relay race in which, like the baton that passes from hand to hand, something not physical, not definable, something like a collection of memories, a store of experiences lived elsewhere, passes from body to body and from death to death, and all the while grows and expands, gathering wisdom and advancing towards that state of grace that concludes every life: towards illumination, in Buddhist terms? That would help to explain my difference from the Terzani clan, and to interpret the blind man’s statement that as a child I was passed from one family to another.

At times we all have the disquieting sensation of having already experienced something that we know is in fact happening for the first time, of having already been in a place where we are sure we have never set foot. Where does this feeling of déjà vu come from? From a ‘before’? That would surely be the easiest explanation. And where have I been, if there is a ‘before’? Perhaps somewhere in Asia, an Asia without concrete, without skyscrapers, without superhighways. So I pondered as I watched the dull, grey streets of Bangkok as they slid past the window, suffocated by the exhaust of thousands and thousands of cars.

My interpreter lived on the outskirts of the city, and I had offered to see her home. The car entered a bit of motorway I did not know. ‘A very dangerous stretch, this,’ she said. ‘People die here all the time. Do you see those cars?’ In the shadows of an underpass I saw two strange vans with Thai writing on them, and some men in blue overalls standing nearby. ‘The body-snatchers,’ said the woman. It was the first time I had heard the word in Bangkok. The story behind it was grisly.

According to popular belief, when a person dies violently his spirit does not rest in peace. And if, in the moment of death, the body is mutilated, decapitated, crushed or torn to pieces, that spirit becomes particularly restless; unless the prescribed rites are quickly performed it goes to join the enormous army of ‘wandering spirits’. These spirits, along with the evil phii, constitute one of the great problems of today’s Bangkok. Hence the importance of the ‘body-snatchers’, volunteers from Buddhist associations who cruise around the city collecting the bodies of people who have died violently. They put the pieces together and perform the appropriate rites so that the souls may depart in peace, and not hang about playing tricks on the living.

Apart from murder victims and suicides, the most obvious candidates for becoming wandering spirits are those killed in road accidents. That is why the Buddhist associations station their vans at the most notorious black spots on the roads, and why their men stand guard, tuned to the police radio frequencies, ready to rush to corpses at a moment’s notice. And they really do rush, for this kind of work has become so profitable that the charitable associations are in fierce competition, and each tries to take away more corpses than the others so as to get more donations from the public. The first to arrive has the right to the body, but the men from the different associations often come to blows over a dead person. Sometimes they carry off someone who isn’t dead yet. To advertise their public service each association holds special exhibitions with macabre colour photographs of the victims, clearly showing the severed heads and hands, so that they can press for generous donations.

That evening Bangkok really felt to me like a city from which there was no escape. Despite the competitive zeal of the body-snatchers, the number of angry phii is constantly increasing. Finding no peace, they wander about creating disasters. In vain have thousands of bottles of holy water been distributed by the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces of Thailand to exorcize the evil eye from the City of Angels, which the angels all seem to have forsaken.

CHAPTER FIVE Farewell, Burma (#ulink_7624d398-bc0c-5896-859f-c4306f2c99dc)

In January I heard that the Burmese authorities at the frontier post of Tachileck, north of the Thai town of Chiang Mai, had begun issuing some entry visas ‘to facilitate tourism’. You had to leave your passport at the border and pay a certain sum in dollars, after which you were free to spend three days in Burma and travel as far as Kengtung, the ancient mythical city of the Shan.

This scheme was obviously dreamed up by some local military commander to harvest some hard currency, but it was just what I was after. I was looking for something to write about without having to use planes, and this was an interesting subject: a region which no foreign traveller had succeeded in penetrating for almost half a century was suddenly opening up. By pretending to be a tourist I could again set foot in Burma, a country from which as a journalist I had been banned.

In Tachileck the Burmese had probably not yet installed a computer with their list of ‘undesirables’, so Angela and I, together with Charles Antoine de Nerciat, an old colleague from the Agence France Press, decided to try our luck. We came back with a distressing story to tell: the political prisoners of the military dictatorship, condemned to forced labour, were dying in their hundreds. We brought back photographs of young men in chains, carrying tree trunks and breaking stones on a riverbed. Thanks to that short trip we were able to draw the attention of public opinion to an aspect of the Burmese drama which otherwise would have passed unobserved. And I had gone there by chance – or rather because of a fortune-teller who told me not to fly.

This is one aspect of a reporter’s job that never ceases to fascinate and disturb me: facts that go unreported do not exist. How many massacres, how many earthquakes happen in the world, how many ships sink, how many volcanoes erupt, and how many people are persecuted, tortured and killed. Yet if no one is there to see, to write, to take a photograph, it is as if these facts had never occurred, this suffering has no importance, no place in history. Because history exists only if someone relates it. It is sad, but such is life; and perhaps it is precisely this idea – the idea that with every little description of a thing observed one can leave a seed in the soil of memory – that keeps me tied to my profession.

The two towns of Mae Sai in Thailand and Tachileck in Burma are linked by a little bridge. As I crossed it with Angela and Charles Antoine, I felt once again that tremor of excitement, so pleasing but rarer as time goes on, of setting foot where few had been and where perhaps I might discover something. This had been a forbidden frontier at one time. There was said to be a heroin refinery just a few dozen yards inside Burmese territory. With good binoculars, you could make out a sign in English: ‘Foreigners, keep away. Anyone passing this point risks being shot.’ Now in its place is one proclaiming in big gold letters: ‘Tourists! Welcome to Burma!’

So, Burma too has yielded to the common fate. For thirty years it tried to resist by remaining isolated and going its own way, but it did not succeed. No country can, it would seem. From Mao’s China to Gandhi’s India to Pol Pot’s Cambodia, all the experiments in autarchy, in non-capitalist development with national characteristics, have failed. And what is more, most have left millions of victims.

At least the Burmese experiment had a fine name. It was called ‘the Buddhist way to socialism’. This was the invention of General Ne Win, who took power in 1962 and imposed a military dictatorship. He tried to spare Burma the severity of the Communist regime that ruled China on the one hand, and the American-style materialist influence that was taking root in Thailand on the other. Ne Win closed the country, nationalized its commerce and imprisoned his opponents, claiming that only in that way could Burmese civilization be protected. In a certain sense he was right, and ultimately this bestowed legitimacy on his dictatorship. In Ne Win’s hands Burma did indeed preserve its identity. The old traditions survived, religion flourished, and the way of life of the forty-five million inhabitants was not thrown into confusion by industrialization, urbanization and mindless aping of the West. By these means a country like Thailand has indeed been developed, but it has also been traumatized.