По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

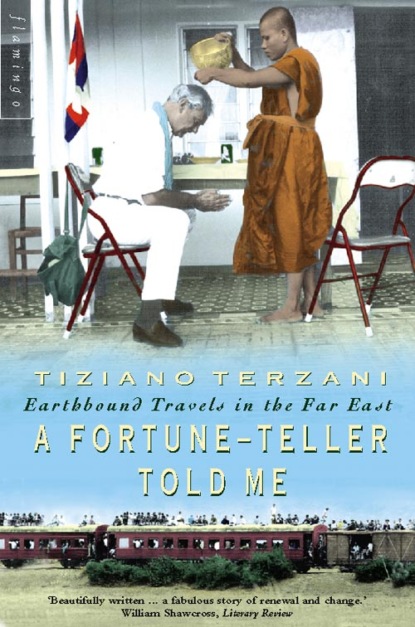

A Fortune-Teller Told Me: Earthbound Travels in the Far East

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Rangoon authorities did not want too many foreigners to ‘pollute the atmosphere’; they doled out visas sparingly, allowing only seven-day visits. Those who went there came back feeling that they had seen a country still untouched by influences from the rest of the world. Burma was a fascinating piece of old Asia, a land where men still wear the longyi, a sort of skirt woven locally; where even women smoke the cheroot, strong green cigars rolled by hand, and not Marlboros; a land where Buddhism is still a living faith and the beautiful old pagodas are still places of living worship, not museums for tourists to stroll around.

That Burma is now about to disappear, too. After a quarter of a century of uncontested power, Ne Win handed over the reins to a new generation of military men, who have imposed a dictatorship more brazen, more violent and murderous, but also more ‘modern’, than the former paternalistic one.

One had only to walk through the market in Tachileck to see that the new generals who are now the masters in Rangoon have dropped all pretence of following ‘a Burmese path’. They have decided to put a stop to the country’s isolation, and have adopted as a model of development the one that for decades has been knocking at their door, as at those of the Laotians, the Khmer and now the Vietnamese: Thailand.

Tachileck has already lost its Burmese patina. It has fourteen casinos and numerous karaoke bars. Heroin is on sale more or less openly. The largest restaurant, two discotheques and the first supermarket are owned by Thais. No transaction takes place in the local currency, the kyat. Even in the market the money they all want is that of Bangkok, the baht.

It is the military and the police who organize tourist visas, who change dollars, who procure a jeep, a driver and an interpreter. I took it for granted that the interpreter assigned to me was a spy, and I managed to get rid of him by offering him three days’ paid holiday. In the market I had been approached by a man of about fifty who seemed more trustworthy. He was a Karen – a member of an ethnic minority hostile to the Burmese; a Protestant, and hence used to Western modes of thought; and he spoke excellent English. Meeting him was a rare piece of luck, because Andrew – a name given him by American missionaries – was a mine of information and explanations.

‘Why are the hills so bare?’ I asked as soon as we left Tachileck.

‘The Thais have cut down the forests.’

‘Whose houses are those?’ I enquired at the first village we came to, where several new dwellings stood out glaringly among the old dark wooden ones.

‘They belong to families who have daughters working in the brothels in Thailand.’

‘And those cars?’

‘They are on the way from Singapore to China. The Wa, they’re no longer headhunters. They’re smugglers.’

‘In heroin?’

‘Only in part. Here in the south they’re in competition with Khun Sa, the real drug king.’

We drove into the mountains, which still looked as if they were hiding a thousand mysteries. In the old maps this part of the world was labelled the ‘Shan States’ because the Shan, who came from China in the twelfth century to escape the advancing Mongols, formed the bulk of the population. The whole region was a sort of living museum of the most varied humanity. Apart from the Shan there were dozens of other tribes living there, each with its own language, its own customs and traditions, its own way of farming and hunting. The encounter with these different groups, of which the Pao’, Meo, Karen and Wa tribes became the best known, was one of the great surprises that greeted the first European explorers in the region.

The long necks of the ‘giraffe women’ of the Padaung, like the tiny bound feet of Chinese women, exemplified Asia’s bizarre aberrations. Even today, the Padaung judge a woman’s beauty by the length of her neck. From birth every girl has big silver rings forced under her chin. By the time she is old enough to marry her head will be sixteen to twenty inches above her shoulders, supported by a stack of these precious collars. If they were removed she would die of suffocation: her head would fall to one side and her breathing would be cut off.

For centuries the Shan have resisted every attempt on the part of the Burmese to dominate them, and have managed to stay independent. The British too, when at the end of the nineteenth century they arrived from India to extend their colonial power, recognized the authority of the thirty-three sawbaws, the Shan kings, and left them to administer their rural dominions, which bore names like ‘the Kingdom of a Thousand Banana Trees’.

In 1938 Maurice Collis, a sometime colonial administrator who became a writer, visited the Shan States and tried to bring to the attention of the British public this unknown wonder of the Empire. Kengtung, with its thirty-two monasteries, struck him as a pearl, and he found it absurd that no one in London seemed to have heard of it. The book he wrote, The Lords of the Sunset – as the sawbaws were called, to distinguish them from the ‘Lords of the Dawn’, the kings of western Burma – is the last testimony of a traveller in that uncontaminated world of peasant kings, where life had been the same for centuries, its rhythm that of old ceremonies, its rules those of feudal ties. I had brought that fifty-five-year-old book with me as a guide.

The road that took us to Kengtung was in places little more than a cart track, barely ten feet wide and full of potholes, often perilously skirting the edge of a precipice, but it was obviously of recent construction.

‘Who built it?’ I asked Andrew.

‘You’ll see them soon.’ Andrew had realized that we were not normal tourists, but that did not seem to worry him. Quite the contrary.

After a few miles Andrew told the driver to stop near a pile of timber at the side of the road. We had scarcely got out of the jeep than we heard a strange clanking sound from the brushwood, like chains being dragged. Yes – chains they were. They were around the ankles of about twenty emaciated ghosts of men, some shaking with fever, all in dusty rags, moving wearily in unison like an enormous centipede, with a long tree trunk on their shoulders. The chains on their feet were joined to another around their waists.

The two soldiers accompanying the prisoners made us a sign with their rifles to drop our cameras.

‘They’re missionaries. Don’t worry,’ said Andrew. It worked. A couple of cigarettes added conviction.

The prisoners put down the trunk and stopped. One of them said he was from Pegu, another from Mandalay. Both had been arrested five years before, during the great demonstrations for democracy: political prisoners, doing forced labour.

It is strange to stand before such an atrocity, be obliged to take mental notes and discreetly snap a few photos, trying to avoid risks and not to give those poor devils more problems than they already had; and then to realize that you have not even had the time to feel compassion, to exchange a word of simple humanity. You suddenly find yourself looking into an abyss of pain, you try to imagine its depths, and all you can think of asking is, ‘And those?’ pointing to the chains.

‘I’ve had them on for two years. One more and I’ll be able to take them off,’ said the young man from Pegu. He was one of the lucky ones: he was wearing a pair of old socks that slightly mitigated the contact of the iron rings with his flesh. Others, lacking such protection, had ugly wounds on their ankles.

‘And malaria?’

‘Lots,’ said the young man from Mandalay, turning mechanically to his neighbour, who was shaking, yellow and puffy-faced. His bony hands were covered in strange stains, like burns. The prisoners – about a hundred in all – lived in a field not far away. Soon we were to see their companions, also chained, breaking stones on the riverbed. These too were guarded by armed soldiers, who would not allow us to stop.

Since the coup in 1988, the massacre of the demonstrators and the arrest of the heroine of the pro-democracy struggle Aung San Suu Kyi, the Rangoon dictators have continued to terrorize the country and to stifle any expression of dissent at birth. Tens of thousands, especially young people, have been arrested and sent to forced labour, used as porters in the army or in fields mined by the guerrillas. Political prisoners are thrown in with common criminals in this forgotten tropical gulag.

‘There are camps like this everywhere,’ Andrew said. ‘Private firms acquire contracts for road-building, and go to the prisons for the men they need. If they die they go back and take some more.’ He had heard that to build the 103 miles of road from Tachileck to Kengtung several hundred men had already died.

It took us seven hours to cover those 103 miles, but by the time we arrived in Kengtung the use of that road was clear to us: it was Burma’s road to the future. Though its original purpose had been to finance the dictatorship and to provide an umbilical cord linking Burma with the neighbouring countries that shared its goals – China and Thailand – by now the road lived by a logic of its own, and served all sorts of people for all sorts of traffic. Communist ex-guerrillas, recently converted to opium cultivation, use it to move consignments of drugs; the Wa, former headhunters, to smuggle cars, jade and antiques; Thai gangsters to top up their supply of prostitutes with young Burmese girls. Thanks to its isolation Burma has, so far, staved off the AIDS epidemic, so these girls, often only thirteen or fourteen years old, are in great demand for the Thai brothels, where thousands of them are already working. At the end of 1992 about a hundred who tested HIV positive were expelled and sent home. Rumour has it that the Burmese military killed them with strychnine injections.

We arrived in Kengtung at sunset. After many miles of tiresome ascents and descents, through narrow gorges between monotonous mountains where the eye never had the relief of distance, we suddenly found ourselves in a vast, airy valley. In the middle of it white pagodas, wooden houses and the dark green contours of great rain trees were silhouetted like paper cutouts against a background of mist that glowed first pink and then gold in the setting sun. Kengtung was evanescent, incorporeal like the memory of a dream, a vision outside time. We stopped; and perhaps, from the distance, we saw the Kengtung of centuries ago, when the four brothers of the legend drained the lake that once filled the valley, built the city, and erected the first pagoda. There they placed the eight hairs of Buddha, which the Great Teacher had left when passing through.

The town was at supper. Through the open doorways of the shop-houses, with dogs on the thresholds, we could see families sitting around their tables. Oil lamps cast great shadows on walls dotted with photographs, calendars and sacred images. There was no traffic on the streets; the air was filled with the quiet murmur of evening’s isolated voices and distant calls.

A fair was in progress in the courtyard of a pagoda. People crowded around the many stalls, lit by small acetylene lamps, to buy sweets and to gamble with large dice that had figures of animals instead of numbers. Wide-eyed children peered through the forest of hands holding out bets to the peasant croupiers. In the shadows, at the feet of three large Buddhas smiling timidly in bronze, a group of the faithful were gathered in meditation. Some women, their long hair gathered in off-centre chignons, had lit fires on the pavements and were cooking sugared rice in large bamboo canes.

There was nothing physically breathtaking about Kengtung – no particularly impressive monument, temple or palace. Its touching charm lay in its atmosphere, in its tranquillity, in the timeless pace of life without stress.

Is it strange to find all this beautiful? Is it absurd to worry that it is changing? In appearance everything is fine these days in Asia. The wars are over, and peace – even ideological peace – reigns, with very few exceptions, over the whole continent. Everywhere people speak of nothing but economic growth. And yet this great, ancient world of diversity is about to succumb. The Trojan horse is ‘modernization’.

I find it tragic to see this continent so gaily committing suicide. But nobody talks about it, nobody protests – least of all the Asians. In the past, when Europe was beating at the doors of Asia, firing cannonballs from her gunboats and seeking to open ports, to obtain concessions and colonies, when her soldiers were disdainfully sacking and burning the Summer Palace in Peking, the Asians, one way or another, resisted.

The Vietnamese began their war of liberation the moment the first French troops landed on their territory; that war lasted more than a hundred years, and only ended with the fall of Saigon in 1975. The Chinese fought in the Opium Wars, and in the end trusted to time to free themselves from the foreigners who ruled with the force of their more efficient weapons. (The last two pieces of Chinese territory still in foreign hands, Hong Kong and Macao, are returning to Peking’s sovereignty in 1997 and 1999 respectively.)

Japan, on the other hand, reacted like a chameleon. It made itself externally Western, copied everything it could from the West – from students’ uniforms to cannons, from the architecture of railway stations to the idea of the state – but inwardly strove to become more and more Japanese, inculcating in its people the idea of their uniqueness.

One after another the countries of Asia have managed to free themselves from the colonial yoke and show the West the door. But now the West is climbing back in by the window and conquering Asia at last, no longer taking over its territories, but its soul. It is doing it without any plan, without any specific political will, but by a process of poisoning for which no antidote has yet been discovered: the notion of modernity. We have convinced the Asians that only by being modern can they survive, and that the only way of being modern is ours, the Western way.

Projecting itself as the only true model of human progress, the West has managed to give a massive inferiority complex to those who are not ‘modern’ in its image – not even Christianity ever accomplished this! And now Asia is dumping all that was its own in order to adopt all that is Western, whether in its original form or in its local imitations, be they Japanese, Thai or Singaporean.

Copying what is ‘new’ and ‘modern’ has become an obsession, a fever for which there is no remedy. In Peking they are knocking down the last courtyard houses; in the villages of South-East Asia, in Indonesia as in Laos, at the first sign of prosperity the lovely local materials are rejected in favour of synthetic ones. Thatched roofs are out, corrugated iron is in, and never mind if the houses get as hot as ovens, and if in the rainy season they are like drums inside which the occupants are deafened.

So it is with everyone these days. Even the Chinese. Once so proud to be the heirs of a four-thousand-year-old culture, and convinced of their spiritual superiority to all others, they too have capitulated; significantly, they are beginning to find it embarrassing still to eat with chopsticks. They too feel more presentable with a knife and fork in their hands, more elegant if dressed in jacket and tie. The tie! Originally a Mongol invention for dragging prisoners tied to the pommels of their saddles…

By now no Asian culture can hold out against the trend. There are no more principles or ideals capable of challenging this ‘modernity’. Development is a dogma; progress at all costs is an order against which there can be no appeal. Merely to question the route taken, its morality, its consequences, has become impossible in Asia.

Here there is not even an equivalent of the hippies who, realizing there was something wrong with ‘progress’, cried ‘Stop the world, I want to get off!’ And yet the problem exists, and it is everyone’s. We should all ask ourselves – always – if what we are doing improves and enriches our lives. Or have we all, through some monstrous deformation, lost the instinct for what life should be: first and foremost, an opportunity to be happy. Are the inhabitants happier today, gathered in families chatting over supper, or will they be happier when they too spend their evenings mute and stupefied in front of a television screen? I am well aware that if we were to ask them, they would say that in front of a television is better! And that is precisely why I should like to see at least a place like Kengtung ruled by a philosopher-king, by an enlightened monk, by some visionary who would seek a middle way between isolation cum stagnation and openness cum destruction, rather than by the generals now holding Burma’s fate in their hands. The irony is that it was a dictatorship that preserved Burma’s identity, and now another dictatorship is destroying it and turning the country, which had so far escaped the epidemic of greed, into an ugly copy of Thailand. Would Aung San Suu Kyi and her democratic followers be any different? Probably not. Probably they too wish only for ‘development’. They too, if they ever came to power, could only allow the people that freedom of choice which in the end leaves them with no choice at all. No one, it seems, can protect them from the future.

Night fell in Kengtung, timeless night, a blanket of ancient darkness and silence. All that remained was a quiet tinkling of bells stirred by the wind at the top of the great stupa of the Eight Hairs. Led by this sound we climbed the hill by the light of the moon, which, almost full, rimmed the white buildings in silver. We found an open door, and spent hours talking with the monks, sitting on the beautiful floral tiles of the Wat Zom Kam, the Monastery of the Golden Hill. That afternoon several lorries had arrived from the countryside full of very young novices. Accompanied by their families, they were all sleeping on the ground along the walls, at the feet of large Buddhas with their faint, mysterious smiles, that glimmered in the light of little flames. Statues though they were, they were dressed in the orange tunic of the monks, exactly as if they too were alive and had to be shielded from the night breeze that came in at the windows. The novices, small shaven-headed boys of about ten, lay wrapped in new saffron-coloured blankets given them by their relatives for the initiation. For years to come the pagoda would be their school – a school of reading, writing and faith, but also of traditions, customs and ancient principles.

What a difference, I thought, between growing up that way – educated in the spartan order of a temple, beneath those Buddhas, teachers of tolerance, with the sound of the bells in their ears – and growing up in a city like Bangkok where children nowadays go to school with a kerchief over their mouths to protect them from traffic fumes, and with Walkmans plugged in their ears to drown out the traffic noise with rock music. What disparate men must be created by these disparate conditions. Which are better?

The monks were interested in talking about politics. They were all Shan, and hated the Burmese. Two of them were great sympathizers of Khun Sa, the ‘drug king’, but now also the champion in the struggle for the ‘liberation’ of this people which feels oppressed.

In 1948, under pressure from the English, the Shan, like all the other minority populations, consented to become part of a new independent state, the Burmese Union, with the guarantee that if they chose they could secede during the first ten years. But the Burmese took advantage of this to wipe out the sawbaw and reinforce their control over the Shan States. Secession became impossible, and ever since there has been a state of war between the Shan and the Burmese. Here the Rangoon army is seen as an army of occupation, and often behaves like one. In 1991 some hundreds of Burmese soldiers occupied the centre of Kengtung and razed the palace of the sawbaws to the ground, claiming the space was needed for a tourist hotel. The truth is that they wanted to eliminate one of the symbols of Shan independence. In that palace had lived the last direct descendant of the city’s founder. His dynasty had lasted seven hundred years. Old photographs of that palace now circulate clandestinely among the people, like those of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa.

When we left the pagoda it was still a couple of hours before dawn, but along the main street of Kengtung a silent procession of extraordinary figures was already under way. Passing in single file, they seemed to have come out of an old anthropology book: women carrying huge baskets on long poles supported by wooden yokes across their shoulders; men carrying bunches of ducks by the feet; more women, moving along with a dancing gait to match the movement of the poles. The groups were dressed in different colours and different styles: Akka women in miniskirts with black leggings and strange headgear covered with coins and little silver balls; Padaung giraffe-women with their long necks propped up on silver rings; Meo women in red and blue embroidered bodices; and men with long rudimentary rifles. These were mountain people who had come to queue for the six o’clock opening of one of Asia’s last, fascinating markets.