По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

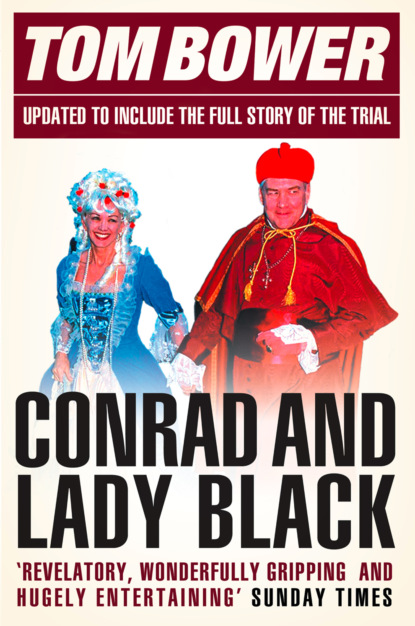

Conrad and Lady Black: Dancing on the Edge

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Newman had been encouraged to cast his subject as an intellectual and a philosopher. ‘Every act must have its consequences,’ Black told Newman, posing as the profound historian who did not believe in redemption or atonement.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘Hal Jackman and I agree,’ he continued, ‘that we’re basically more Nietzschean than Hegelian.’ Black ‘revealed’ his sympathy with the ‘exquisitely sad comment by the seventeenth-century French satiric moralist Jean de la Bruyère that “Life is a tragedy for those who feel, and a comedy for those who think.”’

(#litres_trial_promo) Newman was encouraged to conclude, ‘He has trouble working out any form of understandable motivation for himself.’ Blessed with that smokescreen, Black’s disarming confession, ‘I may make mistakes, but at the moment I can’t think of any,’ was recorded without comment.

(#litres_trial_promo) Despite Newman’s talent, several of Black’s fundamental flaws remained concealed. The cosmetics were impenetrable.

Initially, Black was delighted by the book. Reading his own interpretation of himself fed the conviction that journalists were easily beguiled. Self-interest, however, dictated that he maintain a chasm between himself and potential critics. The publication in Newman’s own Maclean’s of articles describing his Norcen troubles justified that caution. In 1983, fearing further allegations of dishonesty, he issued a writ for defamation against Newman and the magazine. His prosperity depended upon suppressing any objective examination of his fortune-hunting and perpetuating the myth of his being self-made, unblessed by any inheritance: ‘I’m rich and I’m not ashamed of being wealthy. Why should I be? I made all my money fairly.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In 1983 Black was, by the scale of his own ambitions, neither rich nor powerful. His gross wealth was about C$200 million, but most of that was used as collateral against loans. His debt was increasing, and he decided that he would sell Argcen’s (Argus’s successor) stake in Standard Broadcasting and Dominion Stores Ltd. Just as he had failed in mining and oil, so he had proved ineffectual at Standard Broadcasting, the owner of several radio stations, and Radler’s attempts to save Dominion had proved dismal. Newspapers, he agreed with Radler, were their best option. By slashing costs they could make profits, and newspaper ownership would satisfy his craving for political influence. His passion was to own the Washington Post, but more realistically he wanted Southam, Canada’s biggest newspaper chain. The owners, Radler spotted, had borrowed large sums to modernise and expand, but the business was deemed to be unprofitable. Only by making massive cuts would the group earn satisfactory profits. Black and Radler bought a small stake in the company, and made an offer wrapped around an uncongenial pronouncement. Southam, Black sneered outrageously, was run by long-haired, dope-smoking freaks left over from the 1970s. His offer to buy the company was rejected. Black was stuck. Frustrated by Canada’s politics and concerned about his image, he was aware of his shortcomings. ‘I’m a great believer,’ he had told Peter Newman, ‘in not becoming hypnotised by the rhythm of one’s own advancement. I have always felt it was the compulsive element in Napoleon that drew him into greater and greater undertakings, until he was bound to fail.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The ‘compulsive element’ was a characteristic Conrad Black shared with Barbara Amiel. Another common quality was living behind a mask. A third similarity was incompatibility with their spouses. After seven years of marriage the Blacks were irreconcilable, but were in mutual denial about their inevitable fate. Similarly, on 26 January 1985, Barbara Amiel also denied the obvious. Like Conrad Black, she had hoped that happiness would follow her marriage vows to the multi-millionaire David Graham. The expensive wedding party on the thirty-third floor of the Sutton Place Hotel, with a spectacular panoramic view of Toronto, was intended to seal her bliss. Instead, her itinerant search for permanence was doomed. Fate determined that Conrad Black should witness the beginning of her predicted disappointment.

* (#ulink_6ddb429b-41f1-5ee0-9163-20b2d2249b6d) In an agreed swap of shares, Norcen bought 20 per cent of Hanna shares while Hanna sold its shares in Labrador.

3 The Survivor (#ulink_b1973511-f94a-5801-afa2-e36843648e90)

THE ORIGINS OF A WOMAN later renowned as a ‘drama queen’ were remarkably ordinary.

In summer 1940, Barbara Amiel’s parents, middle-class Jews, moved from central London to Chorley Wood near Watford, north of the capital, to escape the Luftwaffe’s remorseless bombardment. On 4 December 1940, the day of her birth, the area around her grandparents’ homes in the East End was blazing. Among the subsequent victims of the incendiary bombs would be Isaac Amiel, her paternal grandfather, the owner of a sweet shop and an air raid warden.

Harold and Vera Amiel greeted their daughter’s birth with joy but understandable fear. The Blitz was the prelude to an anticipated German invasion, and if Britain was defeated, the fate of the country’s Jews was uncertain. Harold Amiel, a twenty-five-year-old solicitor, had joined the Buffs, the Royal East Kent Regiment, and was due to be posted to the 8th Army in North Africa. In his absence his wife Vera, a strikingly good-looking woman of twenty-four, could rely on her family: her sister Katherine, a doctor, and Harold’s three younger brothers and older sister Irene, had also left London. Several of them, including Harold and Vera, had settled in Chorley Wood.

In common with all their relations, Harold and Vera had been born in London’s squalid East End, but long before the outbreak of the war most of the Amiels and the Barnetts (Vera’s family) had escaped from the Jewish ghetto. The new generation, including a midwife, a doctor, a school teacher, an actuary, lawyers and businessmen, had abandoned regular attendance at synagogue and had consciously assimilated into British society. Although the Amiels stemmed from a well-known family of Sephardic Jews from Spain, and the Barnetts were descended from Vladimir Isserlis, an Ashkenazi scholar in Russia, Barbara and her cousins growing up in Chorley Wood were only vaguely aware that their family’s arrival in Britain had followed the discovery of great-grandfather Isserlis floating in the River Dnieper with a knife in his back. To escape the pogroms his widow had sold valuables to buy tickets on a boat sailing to Britain. Sixty years later, the fate of Europe’s Jews was rarely discussed in Chorley Wood. Rather, some families were preoccupied with persuading Britons to support the socialist or Communist parties in the next elections. Irene Amiel’s husband Bernard Buckman, the owner of department stores, was particularly close to two rich Jewish families, the Sedleys and the Seiferts. Together they championed and financed the British Communist Party. Barry Amiel, Harold’s younger brother, was also a member of the Communist Party. Among that group, Harold and Vera Amiel were known to be markedly uninterested in politics.

Vera was also noted as a neurotic, which caused tension during Harold’s return on leave in late 1942. Since their marriage in June 1939 the articulate and intelligent lawyer, now newly promoted as a major, had become disturbed by his wife’s emotions. That concern appeared to be brushed aside as he regaled his nephews and nieces with stories about the war and handed out epaulettes taken from captured Italian generals. The prizes from the battle-front would remain an indelible memory among the boys after they had bade Harold farewell on his return to Africa. In Harold’s absence his second daughter Ruth was born in 1943. One year later, Lieutenant Colonel Amiel’s war ended. Shot in the shoulder by a sniper while riding in a Jeep in Italy, he was repatriated as an invalid. Dressed in his colonel’s uniform, he spent time playing with his four-year-old daughter Barbara, who had struck up a close friendship with Peter Buckman, her older cousin. ‘Will you marry me?’ Peter asked Barbara. ‘We can’t,’ she replied. ‘We’ve both got dandruff, and that means that our children will be bald. I learned that in biology.’

During the last months of the war, Harold arranged to establish a solicitors’ partnership with his younger brother Barry. At the same time, he fell in love with a woman called Eileen Ford. Some would blame the tensions of the war for the breakdown of Harold and Vera’s marriage in 1945; others said that Vera was an uneducated neurotic and an unsuitable wife for a cultured lawyer. Divorce was common in the immediate post-war period, but Vera was unusually incandescent about Harold’s infidelity, not least because she had partly financed his new law partnership.

Despite the Amiels’ ugly arguments about money, Barbara Amiel was more fortunate than the many children who had lost their fathers in combat. Nevertheless, her early childhood was insecure. ‘I’ve suffered from insomnia all my life,’ she would write. ‘My earliest memory as a child of four was being sedated to sleep.’

(#litres_trial_promo) There was, however, support from Mary Vangrovsky, Harold’s mother. After the divorce in 1946 and Harold’s marriage to Eileen in 1948, she gave her son money to set up a new home, and cared for her two granddaughters. By then Vera and her daughters were living in Hendon, in north-west London.

Barbara Amiel’s early school years were comfortable. Although affected by the general post-war austerity and the rationing of food and clothes, she attended North London Collegiate, one of England’s best state schools for girls, and enjoyed the privileges of a middle-class upbringing. There were ballet lessons, excursions to the theatre and cinema, visits to the new Festival Hall to hear Dame Myra Hess play Grieg, and regular meetings with her father at weekends.

(#litres_trial_promo) Forbidden by Vera to entertain his two daughters in his new home, Harold would take the girls to visit their cousins – Anita Amiel in Swiss Cottage and the Buckmans in Hampstead – for lunch and tea before returning to Hendon. In the era of the nationalisation of major industries by the Labour government and the Cold War division of Europe, politics was passionately discussed in many homes, especially by Jews, a number of whom ranked among the leadership of the left-wing parties. Stimulated by the arguments, especially while visiting the Buckmans, Barbara Amiel would recall her growing understanding of their ‘interest in creating a more just society … through socialism’.

(#litres_trial_promo) At thirteen she was an intelligent, socially aware schoolgirl enjoying a stable life. Her mother was considering transferring her to Roedean, the expensive private boarding school on the south coast, but instead opted for a more dramatic change.

In the early 1950s Vera had begun a relationship with Leonard Somes, a non-Jewish draughtsman. Among the Barnetts and Amiels, Somes was regarded as decent and unassuming, but intellectually unimpressive. In 1953 Vera married him and declared that they would emigrate to Canada to find a new life. Amiel would later write that emigration was her mother’s only option, because the British class system discriminated against working-class men like her new stepfather, but that was fanciful. Many ambitious working-class Britons earned fortunes in the post-war era. Leonard Somes’s difficulties were his lack of talent and purpose, and his social unease. Canada, promised the advertisements, was a guaranteed escape from austerity and offered an idyllic future. Barbara’s fate was decided. By then her father had two more children, the elder of whom, a boy, was mentally handicapped. There was no possibility of Harold Amiel caring for his elder daughters.

The emigrants arrived in Hamilton, near Toronto, at the end of autumn 1953. There was disillusion rather than a honeymoon. The job Leonard Somes was expecting had disappeared, and after their savings were spent he was compelled following a long period of unemployment to work as a labourer at a local steel mill. Home life in Tragina Avenue, recalled Amiel, was a desperate ‘rat race’ to ‘make ends meet’. The family’s plight worsened when her mother went into premature labour. Although she and her son survived after weeks in hospital, Amiel was horrified that her mother’s wedding ring had been ‘wrenched from her finger’ by a robber in the hospital’s parking lot.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At fifteen, Barbara Amiel was angry. In place of a comfortable home in London, an excellent school and endless cultural excursions, she found herself marooned in a grim wasteland surrounded by uneducated, insular provincials. Her mother, she screamed, was responsible for the calamity. Relations between Leonard and Vera deteriorated. They decided to move to St Catharines, a nearby town where there was the promise of a better job and a bigger home, a necessity since Vera had discovered that she was again pregnant. The only obstacle was Barbara, and there were furious arguments. Vera condemned her daughter’s behaviour as unreasonable. For her part, Barbara judged her mother to be neurotic and unstable, and she was equally dissatisfied with her stepfather’s lacklustre achievements. Although she would write twenty-five years later that her stepfather was ‘a handsome, warm man of whom I was enormously proud’, at the time she was infuriated by his responsibility for her plight.

(#litres_trial_promo) In her mother’s version of events, there was concern about Barbara’s education. She was settled at the local school, and was ambitious to attend university. The best temporary solution, they agreed, was for Barbara to stay with neighbouring friends and to visit her family at weekends. Accordingly, her clothes were packed and carried to her temporary home.

(#litres_trial_promo) Barbara’s version is more apocalyptic. She describes arriving home from school one day at the age of fourteen to discover all her possessions ‘packed in a cardboard box next to the front door. My mother was very apologetic. “Your stepfather and I can’t cope with you any more, so you have to move out.” They found me a room in a house on a council estate and paid my rent until the end of the school term.’ The publication of Barbara’s account in 1980 would cause great hurt to Vera and Leonard, and to many others in her family who disputed her recollection of events.

Growing up alone without a family became increasingly difficult. In Amiel’s various descriptions, she lodged in a part-time brothel while revising for her high-school exams at St Catharines Collegiate, or was a tenant with an unpleasant Polish family. She kept her concentration by stuffing her ears with wax earplugs, but after the ‘hurt had passed and I had cried a bit, after I got over the fright of sleeping in cellars underneath the furnace pipes, I came to cherish my freedom’. During her adolescence, she would also write, she found herself ‘in the middle of a room, stranded, sitting in my own urine, sitting for hours, too frightened to cry and too frightened to move’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Her occasional companions in sexual experimentation and drinking alcohol were the children of Polish émigrés and Canadian aboriginals. To accommodate that lifestyle she moved into a boarding house during the week, and stayed with a succession of girlfriends’ families at the weekends. To finance herself, she worked in the evenings and holidays, in a drugstore, a fruit-canning factory and clothes shops. Illness forced her once to return temporarily to her parents’ home, but she soon resumed life in Hamilton. Told she was entitled to a ‘secure home’ by a social worker, she later commented, ‘I had never thought about what I was entitled to. Things were simply taken as they came.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Her brave struggle was rewarded by her securing the grades to study philosophy and English at the University of Toronto. Amiel had become a toughened, streetwise survivor. Her ‘wild’ days, she would write thirty years later, left a legacy. ‘Something decent died in me, or perhaps was stillborn: I would never be able to create a successful family life.’ Incorrect reports suggested that she never saw her mother again.

(#litres_trial_promo) Her anger at Vera was compounded by another surprise. In 1959, on the eve of going to university, she and her sister were invited by their family to return to England for their summer holidays.

Unknown to Amiel, in early 1956 her father had become severely troubled. Harold Amiel, the practice’s accountant, had been stealing money from clients and from his solicitors’ partnership. Exposure was imminent. Fearing disgrace and the anger of his younger brother Barry, he went on 19 April to his mother’s flat in Marylebone while she was on a winter cruise, and took an overdose of barbiturates. A verdict of suicide was declared by the coroner one week later. In their grief, the families decided not to tell Harold’s two daughters in Canada, partly because he rarely talked about them, and also because he had not mentioned them in his last will, signed the day before his death. Barbara’s cousins were told that Uncle Harold had died of his wartime wounds. Amiel’s sole memento of her father was a photograph of him dressed in a colonel’s uniform. Many years later she described her father swallowing the tablets while listening to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

(#litres_trial_promo) In contrast, Barry Amiel recalled that his brother was reading a good book and eating an apple before his death.

Considering her hardships over the previous six years, Barbara Amiel’s arrival at university had been achieved at a price. Emotionally she was unstable. To relieve her stress and tiredness she swallowed a dozen Codeine 222 tablets a day, and took antidepressants to help her sleep. The physical result was an undernourished, sultry young woman with deep black shadows under her eyes. Sprawled across the bed in her room in the students’ hall of residence were panda bears and other soft toys. On a shelf was the solitary photograph of her father in uniform. ‘Welcome to the Jewish Common Room,’ laughed fellow-student Larry Zolf as the thin Barbara entered the Junior Common Room. ‘The most beautiful fellow-travelling Marxist I have ever seen,’ was Zolf’s conclusion after a few conversations revealed her fascination with Stalin, ‘and certainly the most intelligent.’ Curious about her past, Zolf asked the shy girl about her family. ‘Oh, my father was very poor and unemployed,’ replied Amiel, ‘and we were kept afloat by a rich uncle.’ Other family members do not recall those circumstances.

Sitting regularly in the JCR, the centre of her social life, with her new best friend Ellie Tesher, Amiel confessed her need for security. ‘Who’s that?’ she asked when a handsome, dark-haired student walked in. ‘That’s Gary Smith,’ replied Tesher. ‘He lives in Forest Hill’ (an affluent area of Toronto). ‘I think I’ll marry him,’ said Amiel flatly.

Gary Smith, a gentle, quietly-spoken law student, was the son of Harry Smith, the owner of the once-famous Prince George Hotel in Toronto and a member of a well-known family. In 1958 Harry Smith had opened the luxurious Riviera Hotel in Havana, Cuba, in partnership with Meyer Lansky, the Mafia boss, who owned the hotel’s casino. Fidel Castro’s revolution one year later terminated their investment. In an attempt to recoup some of their money, Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis Jr and Sophie Tucker were booked to appear at the Prince George Hotel, and the income their performances generated was substantial. The downside was Harry Smith’s chronic and unsuccessful gambling in casinos across the USA. Nevertheless, to Barbara Amiel, the Smiths appeared a wealthy, stable Jewish family who might offer her salvation.

Amiel enjoyed Gary Smith’s adulation. Silently, he admired her skills in political argument – the legacy, she said, of those family debates in north London. As her self-confidence grew, she became the centre of attraction in student debates as a fiery supporter of neo-Marxism and Leon Trotsky. ‘You don’t know the difference between Trotsky and a hole in the ground,’ laughed Zolf. Once their relationship had become established, Smith was untroubled by Amiel’s frequent indifference towards him, even when she treated him like an imbecile. Gladly he satisfied her craving for cashmere sweaters, her enjoyment of expensive trips and, at the weekends, her desire to smoke pot and win at Monopoly. ‘Sex is good with Barbara,’ Smith confided, albeit that it invariably took place in the back of the car he borrowed from his parents – by no means an uncommon experience among their age group. Her thin waist and large, high breasts were breathtaking. ‘If anything,’ Smith murmured, ‘Barbara needs breast reduction, they’re so huge.’ Many years later, Conrad Black was to make the same type of comment publicly. Smith had never met such a sexually experienced woman who frequently took the initiative. His placid temperament could easily cope with her dramatic, even histrionic moods, but while Amiel was vitriolic in criticising others, she was vulnerable to even friendly mocking of herself. In those helpless moments he provided the support she needed, especially during the weeks when she consulted the college psychiatrist about her hallucinations and her growing addiction to Codeine. A doctor prescribed Elavil, an antidepressant. ‘The drug,’ she wrote, ‘was to be my undoing [and the cause of] my erratic emotional life … I never realised quite how drugged I was for those seven years.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Amiel’s erratic life had started long before the summer of 1962, but that year was a landmark. Isaac Barnett, her grandfather, died and bequeathed her £400. She flew to London with Gary Smith to collect the money and see her family. In the new, exciting environment, Amiel’s imagination let rip. Smith was under the mistaken impression that she had found her father’s corpse after he committed suicide, and she suggested that she had been brought up as a Marxist, mixing with the Seiferts and Sedleys, the rich Jewish Communist families who lived in mansions in Hampstead, although neither family could recall her presence in their homes, or her being invited to their frequent parties. She would later recollect that she was met at Heathrow by ‘my Maoist uncle’s chauffeur’, while Gary Smith recalls them taking a bus into the city and walking to a hotel.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Amiels and the Buckmans recall trying their best to care for their niece whose innocence had, it seemed, been irretrievably lost. As a gesture of their consideration, her uncle Bernard Buckman suggested that she join the British delegation to that year’s World Youth Festival in Helsinki, a Soviet-sponsored summer camp for Communist supporters. Amiel bade farewell to Gary Smith and set off, passing through the newly-built Berlin Wall, to compare the theory of Communism discussed at university in Toronto with the reality.

Eighteen years later, Amiel would assert that the Helsinki experience had immediately and fundamentally changed her political opinions, although the student who returned to Canada still spoke as a Marxist. The noticeable difference was her change of personality. The shy trepidation had been replaced by a flaunting of her sexual attractions. With her family’s support, she did not need to work that summer. Instead she stayed with Florence Smith, Gary’s aunt, while he continued to live with his parents.

Despite her growing dependence on the Smiths, Amiel’s visit to Helsinki did bring about one basic change – she began to live a double life, which would continue until she married Conrad Black. She would travel to Montreal, moving in circles where people played with ‘real drugs’, and discovering that she got high on marijuana more quickly if she used a pipe. While apparently faithful to Gary Smith, she also enjoyed other sexual relations.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Canadian idol of the era was Leonard Cohen, the brilliant, handsome poet and singer. Cohen’s philosophy appealed to countless female admirers who flocked to the star in the hope of seducing him. Amiel suggests that she joined the queue. Cohen, she said, could offer women ‘everything, except of course fidelity … In his own terms he is not unfaithful to anyone because he cares for them all.’ The poet’s attitude towards free love and open relationships, while caring for all his lovers, appealed to Amiel’s gypsy temperament.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘The secret that Leonard shares with Casanova,’ she would write, ‘is the one that costs him dear: it is real desire.’ Amiel showed the same unfaithfulness, but in her case it was to satisfy different requirements. She always needed a man, but hated relying on other people. Her dilemma was how to balance her dependence and her desire for independence. Unlike Cohen, she would not advertise her roaming, astutely compartmentalising her life.

Just after completing her final university examinations in 1963, Amiel opted for financial stability. ‘I wrote a message under the seal of your degree,’ she told Gary Smith, referring to a romantic gesture she had made while preparing the degree certificates in the university administrator’s office. ‘It’s a love message,’ she confided. Days later, at the end of a sexual session in Gary’s father’s car, she unexpectedly snapped, ‘Let’s get married.’ Gary understood the reasons. Barbara was fed up with sex in the back of a car. She wanted a bed, security and, above all, money. Their first date for the ceremony was abandoned. ‘We’ve got cold feet,’ Gary told his parents. A few weeks later they were married in a rabbi’s study in front of eight witnesses including her mother and Leonard Somes, Gary’s parents and Larry Zolf. At the party afterwards in the Smiths’ family apartment, Zolf pushed through gamblers, bookmakers and scam artists to ask a small man, ‘Are you Meyer Lansky?’ ‘So what if I am?’ he growled.

The newly married couple rented an apartment on Toronto’s Spadina Road, and while Gary Smith began his career as a lawyer, Amiel was employed as a secretary and script assistant in the television section of CBC. Not long afterwards, there was a terrible shock. Harry Smith, having lost all his money gambling, was arrested with his brother and accused of fraud. Soon after, he was convicted and imprisoned. Instead of joining a stable Jewish family, Amiel had associated herself with criminals. It was not long before she realised that her decision to marry Gary Smith had been short-sighted. Domestic life with the modest lawyer was dull compared to the thrills at CBC, especially following her appearance on the cover of Toronto Life magazine. Increasingly, she returned home late and too tired for sex. Just nine months after their marriage she asked her husband, ‘Do you know what I’m thinking?’ ‘I would not presume to know what’s going on in your head,’ replied Smith. ‘This isn’t working. I’m off.’

Late that night in summer 1964, George Jonas, a twenty-nine-year-old Hungarian émigré also employed by CBC, was driving along Spadina Road and spotted Amiel crossing the street, ‘weighed down with more baggage than a ten-hand army mule’. ‘Don’t tell me,’ said Jonas. ‘You just robbed a dwelling and can’t remember where you parked the getaway car.’ ‘Close,’ she replied. ‘I just split up with my husband.’ ‘Great,’ said Jonas. ‘Let’s go have coffee.’ ‘Can’t,’ said Amiel. ‘Have to unload all this stuff before seven. Call me tomorrow if you like.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Jonas, a right-wing intellectual, was an unusual character in Toronto. Alternately, he dressed in black leather and rode a motorcycle or assumed the mantle of a Central European, carrying a silver-headed cane as a prop to his hand-kissing and heel-clicking. In London or New York his act might have been ridiculed, but Amiel was attracted to the ambience of an East European intellectual’s home filled with books, music and passionate arguments. Since her visit to Helsinki she had moved from the far left towards the political centre, and Jonas’s fervent anti-Communism was appealing. For his part, Jonas said, ‘I found her very attractive and thoroughly unpleasant.’