По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

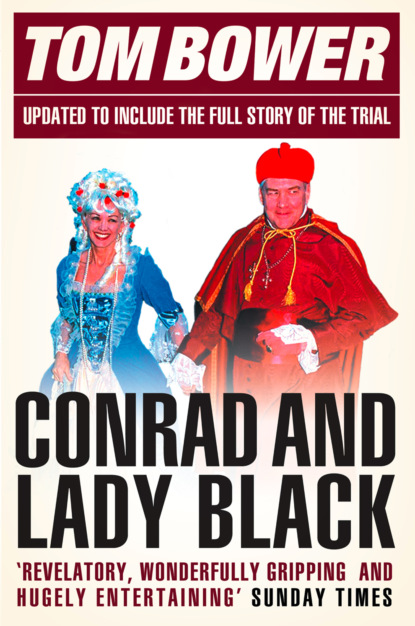

Conrad and Lady Black: Dancing on the Edge

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The contrast between Amiel writing her book in Sam Blyth’s unkempt home, even wearing a coat when the electricity was cut off, and her personal credo was notable. ‘I knew what I wanted,’ she wrote about her time in London in 1971. ‘To be dropped at Selfridges’s or Harrods to pick up fresh salmon and search for quails’ eggs,’ besides taking lessons to be a hostess and sharing a masseur with Lady Weidenfeld.

(#litres_trial_promo) She had become envious of the Canadian jet set’s use of private planes, ‘clubby travellers wafting across borders with sleek impunity’, living ‘our fantasies’. Her reality check was a conviction that those birds of paradise had no ‘durability’ and that few would survive.

(#litres_trial_promo)

More revealing, considering her future conduct as Lady Black, was her attitude towards materialism. ‘The true spirit of liberalism,’ she wrote, ‘simply judges everyone on his or her own merit … We are all responsible for ourselves. That is not callous. That is liberation.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Transgressors, she warned, would be punished: ‘Greed can be held in check by ordinary criminal laws.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Her most pertinent comment, in the light of Conrad Black’s problems twenty-three years later, was her reproach, in Maclean’s, of John Dean, Richard Nixon’s dishonest legal adviser in the White House during the Watergate scandal. Amiel was scathing about Dean’s ‘moral myopia’ as a party to the President’s cover-up. Instead of accepting personal responsibility for his conduct, she wrote, he ‘still clings to the soothing thought that it was all somebody else’s fault’, blaming ‘the environment [for his crimes] rather than a person’s own morality’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In January 1981, soon after the book’s publication, Amiel and Blyth visited Mozambique. She wanted to witness the damage wreaked by Western aid on native agriculture while sustaining Marxist regimes. The journey ended in embarrassment. Attempting to enter the country without visas, they were arrested and imprisoned for some days. She would later claim to have eaten her press pass to avoid recognition. ‘That would have been difficult,’ said Peter Newman. ‘It’s plastic.’ Others quipped that the hardest bit to swallow would have been Newman’s signature, or her own. Amiel’s plight, and her melodramatic plea that her life was in danger, provoked anger from the Canadian ambassador, who was irritated by her behaviour, and from rival journalists. But Peter Worthington, the editor of the Toronto Sun, was surprised by the apparent jealousy. ‘She’s sailing through life like the Spanish Armada,’ he said, apparently unaware that the Armada was destroyed by the English navy and a storm. Amiel’s values and humour, he decided, were ideal for his newspaper. On her return she was appointed a columnist on the Sun, and her life became even more hectic.

Living in squalor with Blyth while renting a comfortable apartment in Forest Hill, she wrote regularly about her abortion, her drugs, her family feuds and her love life. Playing the Jewish card, the impoverished Jew became the aggrieved Jew championing prejudice. Her private life became as varied as her writing. ‘I’ve got this penchant for young men,’ she told a girlfriend. Blyth became just one of several young boyfriends, including twenty-four-year-old journalist Daniel Richler, whom she met during a radio debate. Their affair began soon afterwards. Arguing and laughing in restaurants, Amiel was carefree about her reputation. Just a month after starting the relationship with Richler, there was a silence followed by a sigh during a telephone conversation. ‘This isn’t going anywhere,’ she declared. The relationship was over. Her ‘penchant’ was for other young men, including Eric Margolis, a freelance journalist specialising in the Middle East whom she met at a lunch hosted by one of her many admirers. The host’s misfortune was that Amiel, impressed by Margolis’s charm and expertise about Islam, decided to pursue him. ‘I’m coming over,’ she announced in a telephone call. ‘I’ve got another date,’ replied Margolis. But finally he succumbed, and discovered what he called ‘an Act of God’, Amiel’s breasts. To her irritation, Margolis was too independent, frequently rejecting her suggestions that she visit his flat. ‘Is there someone else there tonight?’ she asked. If Margolis answered ‘Yes,’ she was sufficiently liberal to cope. But if he replied ‘No, I’m working, babe,’ she became incensed, repeatedly calling, seeking to change his mind. ‘You’re like one of the boys,’ laughed Margolis.

At the age of forty-one, Amiel had reached a crossroads. Fearing loneliness, she was seeking marriage in order to have children and embed her social and professional ambitions. Margolis, she decided, was ideal to give her life that structure. He was intelligent, independent and good fun. Frustratingly, he did not show the obedience she liked in her men, and was patently weary that she always wanted to win her point. Amiel could not resist bickering that he should be rich and famous. A fraught ten-day trip to Hong Kong and China ended with her demand, ‘Marry me!’ ‘No,’ he replied, ‘I’d end up in jail.’ ‘Why?’ she asked. ‘Because I’d wring your neck.’ Amiel did not give up her marital ambitions despite an overture from a new admirer. In 1983 Peter Worthington offered her the editorship of the Toronto Sun’s comment section. She would, Worthington believed, succeed as the newspaper’s ambassador for ideological conservatism, providing a public profile on TV shows to attract the Thatcherites among Canada’s East European migrants. To celebrate her appointment she was taken by Doug Creighton, the Sun’s publisher, to Winston’s. There are two versions of what followed during the lunch.

In the first version, Creighton asked Amiel in a loud voice, ‘Are you fucking Peter?’ The restaurant fell silent to hear the answer. Amiel jumped up and ran to the lavatory. According to the second version, Creighton kept naming Worthington. ‘Why do you keep mentioning Worthington?’ Amiel asked. ‘Well, he was your predecessor, he hired you, and he trained you as editor. I’m just trying to say he’s gone.’ Waiting for a moment of silence, Amiel screeched, ‘You think I’m fucking him, don’t you?’ Creighton was nonplussed, but replied, ‘Yes.’ ‘Well,’ she said, ‘I’m not.’ Worthington’s explanation of the exchange is benign: ‘Doug was mesmerised by her. She dazzled him. He was persuaded that she was a bombshell.’

Worthington issued the invitations to Amiel’s appointment party: ‘The Sun has a new editor. It’s a girl.’ Transfixed by Amiel, Worthington became unhappy that Eric Margolis was asked by Amiel to edit the comment section in her absence. The triangle could lead to the farce of Worthington calling at Amiel’s flat while she was at Margolis’s. There was gossip that on one occasion Amiel was standing outside Margolis’s flat, waiting for another woman to leave, while Worthington stood outside Amiel’s flat, waiting for her to return. Amiel’s eccentric personal life and odd hours spread into the editorial newsroom. Either she arrived dressed in a chocolate-brown velour tracksuit, looking harassed with unkempt hair and sunglasses, or she appeared as carefully groomed as a Vogue model. ‘Either a bag lady or a $1 million outfit,’ commented Worthington. On one occasion she strode purposefully past Christie Blatchford, one of Canada’s notable columnists, wearing an ‘open trenchcoat, under which could be clearly seen a black bustier, garter belt and fishnet stockings’. Amiel’s gyrating moods were experienced by Allan Fotheringham, another columnist and an occasional boyfriend, during a trip to Vancouver. After flying 3,000 miles to a gathering of theologians, Amiel felt inclined to shock. Ten minutes after arriving at the party, Fotheringham was surprised to hear her shrill ‘Fuck!’, followed minutes later by a loud ‘Cocksuckers!’ Soon after, the two were standing alone in the garden. The theologians had fled into the house.

By 1984 Amiel’s limitations as an editor were causing even Worthington unease. While she was appreciated by some women journalists as an intellectual, fun, right-wing babe, Worthington marked her down as ‘a dangerous writer’. She was, he decided, ‘not an original thinker but a clear thinker. She marshals other people’s ideas and then personalises them. She knows how to get under people’s skin and find their Achilles heel.’ That talent was inadequate when the news broke of Britain’s response to Argentina’s invasion of the Falklands in April 1982. Amiel needed guidance about ‘our line’. Repeatedly she tried to call Worthington, who was out of reach climbing mountains in China. In desperation, she telephoned George Jonas. ‘I’m against the British,’ said Jonas. So that was the Toronto Sun’s line, and Jonas was given a column as a poet and later as a commentator. Amiel’s attitude did not inspire loyalty. ‘Her people skills are not great,’ sighed Worthington. ‘She’s focusing on people she likes, and she’s not happy working in the background instead of the spotlight.’

Amiel had reached yet another crossroads. Margolis, she decided, was a bon vivant, uninterested in commercial success. The relationship, she concluded, just like her other concurrent affairs, was pointless. In 1982 she had met David Graham, the good-looking, rich stepbrother of Ted Rogers, Canada’s leading communications mogul. Four years older than Amiel, Graham represented upper-class wealth from the Ottawa Valley. Relationships with WASP businessmen, she decided, were less complicated than with men of mixed European backgrounds. ‘A relatively simple person,’ she would write, ‘can be a very attractive quality in a lover.’ By ‘simple’ she did not mean ‘unintelligent’, just not ‘psychologically complex’. Complexity, she decided, ‘is an awful pain in the neck in lovers. It can create mood swings, whining and sometimes meanness [because] good lovers paradoxically want to please no one but themselves.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Graham was, she decided, uncomplicated, and therefore a good lover. To keep everyone on their toes, she introduced the new to the old. Margolis met Graham, and smiled his lack of concern. Amiel chose Graham, not suspecting that twenty years later Margolis would own a multi-million dollar vitamin company with over three hundred employees. ‘I’m hankering for David,’ she told a friend. Committing herself to Graham reflected her desperation for domesticity and a child.

Graham, renowned for his many relationships with glamorous women, wanted a home-maker in London, but was casually unspecific about his other requirements. A beautiful, intelligent woman was appealing, but marrying a forty-four-year old Jewish libertine who paraded her ‘erratic emotional life’, implying sexual promiscuity, was an untested experience. At least there was good reason to believe that Amiel had abandoned her pose as an opinionated, left-wing hippie. Recently she had praised the virtues of wealth and comfort. ‘I so loathe the permissive, promiscuous society,’ she had written, ‘and so long for fidelity, stability and monogamy, but it is always just out of my reach. There is a thing called discipline. I have tried to inflict it on my work. I’ve tried to inflict it on me. But all that emerges is self-indulgence. Really, I won’t talk about my personal life, because I am ashamed of it.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

One minor forewarning for Graham of the perils of cohabiting with Amiel occurred at the wedding of Roy Faibish, a Canadian television producer and political adviser, at Chelsea Register Office in London. Amiel arrived with Graham, and met the CBC TV producer Patrick Watson with his girlfriend Caroline. ‘She’s so cute,’ said Amiel. ‘You’ve been together for some years. I always marry the men I sleep with.’ This carping comment to someone who was familiar with Amiel’s career at CBC provoked a blistering argument in front of thirty guests. Graham noted his fiancée’s independent spirit. Unlike other women, she had achieved fame on her own account, without depending on a rich husband’s wealth. Marrying her would not expose him to a financial liability – in fact she could be generous – but harnessing her strong character would be a challenge .

On 2 July 1984, while visiting Nantucket, off the coast of Massachusetts, Barbara Amiel and Graham married. Soon after the ceremony, Graham was badly injured in a car crash in France. After his recovery Amiel decided to celebrate the marriage again in Toronto, and to host a party at the Sutton Place Hotel.

No man in ‘33 Stop’, the hotel’s summit banqueting room, could have appeared to be less attractive to Barbara Amiel than Conrad Black. The two had met in 1979, at a dinner party in Toronto hosted by Black’s friend John Bassett, and had since discovered that they shared conservative opinions. The eventual union of two insecure Canadians dreaming of glamour, fame and fortune among the jet set could have been predicted by no one.

4 Salvation (#ulink_e8704fbe-d53a-5805-aa05-8aa3ea06025c)

CONRAD BLACK DROVE AWAY from Barbara Amiel’s wedding party in a bad mood. Having agreed to give Allan Fotheringham a lift in his limousine, he discovered that his companion was drunk. He didn’t like Fotheringham. The journalist had a habit of telling the truth about the aspiring press tycoon, and one truth was that Black’s finances were not in good shape. He was determined that in the future he would have his revenge. ‘As [Fotheringham] stepped out of the car,’ Black would write years later, ‘he fell flat in front of the doorman.’ Although the story was denied by Fotheringham, Black ordered his editor to run it anyway: ‘Let him sue.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Black disliked most journalists. Their ‘sanctimonious and tendentious’ assertion of independence while greedily grabbing his dollars was as irksome as their refusal to accept his own judgement of himself. In public testimony he had once damned journalists as ‘a very degenerate group. There is a terrible incidence of alcoholism and drug abuse.’ Since then, his contempt had increased as he and David Radler struggled to build a newspaper business.

The original $500 investment in the Knowlton Advertiser in 1966 had grown into the American Publishing Company. The slender profits depended upon Radler’s constant criss-crossing of the country searching for savings and imposing cuts, and monitoring the financial results on a primitive central computer. Radler’s gospel never changed: ‘Count the chairs,’ he habitually ordered. Halving the number of employees was his familiar recipe, regardless of the consequences for the newspaper’s quality. Having exhausted the search in Canada, the two men began scouring America for small community newspapers with circulations as low as 5,000. In particular they wanted free shopping publications, weekly and community newspapers enjoying monopolies and a lot of advertising. By 1986 they owned eighty daily newspapers in thirty states, and fantasised about creating an empire to rival the two Goliaths, the Washington Post and the New York Times. In the meantime Black would have been satisfied with Toronto’s Globe and Mail, but he had recently been outbid by Ken Thomson, not least because under Black’s control the newspaper would have been made to reflect his conservative opinions. ‘I hate its leftish, pompous tenor and the editor’s smarmy pretensions,’ he had said. Ever since, the Globe’s journalists, he believed, had been unfairly scrutinising his business. He heard that the newspaper’s editors were planning an article describing ‘a rapacious, right-wing Bay Street baron’ who ‘milked’ his businesses, ‘destroyed public companies’ and oppressed minority shareholders ‘in a series of complex corporate shuffles designed primarily to fill his own coffers’.

Throughout his life, Black had cared little for the working classes. Politicians, he believed, should encourage and protect the rich rather than mollycoddle the poor. His true colours had been shown at Massey-Ferguson, and in 1985 he expressed similar ire against the employees of Dominion Stores. Radler’s attempt to revive the supermarket chain had failed. Selling the whole company to one buyer had proved impossible. The shabby supermarkets, Black knew, could only be sold piecemeal and the workers given compensation for losing their jobs. He blamed the staff for his predicament. Accusing them of gross larceny, he sniped in public, ‘Lobsters are walking out of my stores.’ The suggestion of theft was akin to throwing fuel on the fire, but Black enjoyed watching the effect of his provocation. ‘I’ll win,’ he told a friend, ‘because I say these things in such an erudite way.’ His verbal assault disguised the true reasons for the sale. Ravelston’s debts had risen to C$150 million, and the banks were pressing for repayment of loans worth C$40 million advanced to Dominion. Some whispered that Black was on the verge of bankruptcy.

(#litres_trial_promo) His salvation, he decided, was the Dominion Stores pension fund. To profit from the company’s sale, he anticipated using much of the fund’s C$62 million surplus for redundancy payments and to repay the company’s loans, a potentially permissible if controversial move. With skilful negotiation, he persuaded the Pensions Commission of Ontario to authorise his appropriation of those funds.

(#litres_trial_promo) The commission’s approval provoked outrage among trade unions. ‘He’s the representative of bloated capitalism at its worst,’ complained one prominent politician. Thrilled to engage in verbal combat, Black accused his critics of being ‘a symbol of swinish, socialist demagoguery’. The trade unions sued the Pensions Commission, claiming that legal requirements were unfulfilled. At the Globe and Mail journalists began investigating Black’s handling of his employees’ pension fund. The article would conclude, ‘He has been wrong when found with his hand near the cookie jar.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Black was once again a hate figure, and the banks were alarmed. Under pressure to sell his assets, including his private plane, he became ill, damaging his relations with his brother Monte, who was in the midst of an acrimonious divorce. Unexpectedly, Monte agreed to sell his equal interest in the business for $22.4 million, some suspected because he had proven to be unhelpful to his brother’s schemes. Conrad later justified the transfer as a scheme to help Monte avoid a more expensive divorce settlement. Black raised the purchase money by mortgaging his homes in Palm Beach and Toronto. The comparatively small amount exposed the limited value of the Blacks’ business. Their inheritance and the opportunities after the Argus coup had been squandered. Instead of glorying in his status as a global billionaire, Black was slithering along Bay Street sucking a lifeline.

Monte’s replacement as finance director was John ‘Jack’ Boultbee, an aggressive tax planner.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘Jack will bring some imagination to our accounts,’ Black told a friend. Physically, Boultbee was hardly attractive. His hair was dyed black, his suits fitted badly over a paunch, and there were ugly gaps between his teeth. For professional rather than aesthetic reasons, he remained hidden from public view, known as ‘the man behind the curtain’. After his appointment, Black and Radler made no decisions without Boultbee’s scrutiny and approval. He became the brains behind all their schemes, and expected to be rewarded accordingly.

Jack Boultbee had little time to settle into his new position. A Canadian court overruled the Pensions Commission and ordered Black to return C$37.9 million to Dominion’s pension funds. Simultaneously, Don Fullerton, the head of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, told Black, his friend and a fellow director, to repay a C$40 million loan. After selling his 41 per cent stake in Norcen for C$300 million to repay his debts, Black once again reassessed his business. Eight years after the Argus grab, everything had been sold except the collection of small newspapers. Some of Argus’s shareholders complained about the fate of the company’s assets, although Black denied any wrongdoing. Posing as the great capitalist entrepreneur, he had accomplished a vanishing trick, and everyone appeared to have lost money.

During 1985, with Radler and Boultbee’s help, Black again restructured his business. In discussions between them, Boultbee offered ‘scenarios’ to produce profits and avoid taxes. Each one was offered to lawyers and accountants with a request: ‘Will it play?’ If approved, there was a professional’s letter – a ‘good housekeeping certificate’ – giving the trio approval to proceed to the edge of legality. In the succession of complicated transactions, Black once again appeared to his critics to have legitimately profited from asset stripping and insider dealing.

(#litres_trial_promo) Sterling, the company controlling his newspapers in Canada, was sold to Hollinger, also owned by Black, for $37 million, which he took in Hollinger shares. Most of the cash ended up as management fees in Ravelston, his private company.

Those events had spurred the Globe and Mail to finally publish their investigation, under the headline ‘Citizen Black: Can a Right-Wing Tycoon Buy his Way into the Press?’. Black did not appreciate the criticism. He blamed the ‘Canadian spirit of envy’ for failing to glorify tycoons like himself. With delight, he announced that he would sue the Globe to ‘painfully punish’ his critics by forcing them to prove that his dealings were dishonest. That hurdle, as the newspaper’s lawyers soon discovered, would be more than difficult to surmount.

Black drew strength for his battle from the like-minded supporters of raw capitalism gathering in May 1985 for the Bilderberg Conference at Arrowhead, near New York. He regarded his fellow guests as close friends, akin to his family. Among them was Andrew Knight, the editor of the Economist. Knight was more than an intelligent, genial, successful editor. As a global networker, he was entrusted with indiscretions and secrets. ‘Let’s have another fiery Armagnac,’ Black suggested. Over several drinks after midnight, Black confided his frustration at having failed to buy a major Canadian newspaper. Naturally, he omitted mentioning the distrust of himself in his own country. ‘Canada’s a backwater,’ he complained. ‘I sometimes wish I was an American and could own the Washington Post.’ ‘If you’re looking for a big newspaper, Conrad,’ replied Knight, in what would undoubtedly be the most decisive sentence ever uttered in Black’s career, ‘the Daily Telegraph might be a possible target.’ Too much Armagnac had flowed for Knight to notice Black’s reaction.

The Telegraph was among the world’s most successful broadsheets, selling 1.2 million copies daily, 750,000 more than the London Times and 300,000 less than the New York Times. But the headline success disguised dire problems. The Telegraph’s sales were 300,000 lower than five years earlier, and the company was losing about £1 million a month. The reasons were painful. Compared to its rivals, the Telegraph’s advertising revenues had fallen steeply, and the trade unions were effectively blackmailing the company. Every year the employees hired to compose, print and distribute the newspaper were illicitly pocketing millions of pounds, either by threatening to strike just before the paper was due to be printed, or by signing on under names like ‘Mickey Mouse’ and disappearing to work in another newspaper or as taxi drivers. Within its decrepit headquarters in Fleet Street, the Telegraph’s ageing executives appeared helpless, and refused to recruit younger experts to stem the haemorrhage of money.

Isolating himself in a sanctum on the top floor of the Telegraph’s building was Lord Hartwell, formerly Michael Berry, the newspaper’s seventy-five-year-old chairman and editor-in-chief. Abstemious and shy, Hartwell cared passionately about journalism, reading every word he published. His solution to the trade unions’ theft was radical. Two modern printing plants were under construction in London’s Docklands area and in Manchester. By using computers rather than traditional printing craftsmen, he could expel his dishonest employees from the industry forever. Hartwell’s experts had estimated the modernisation would cost £130 million.

One aspect of the Telegraph’s poor management was the inaccurate accounts prepared by Coopers Lybrand, the auditors. Consistently, the company’s costs were underestimated. The Telegraph’s drift towards insolvency had remained unnoticed until, halfway into the Docklands plant’s construction, Hartwell was told that the building costs had increased by £89 million. Unperturbed, he asked his old friend Evelyn de Rothschild, the chairman of the merchant bank N.M. Rothschild, to find lenders on the market. Trusting the famous bankers to care for his interests, Hartwell approved Rothschild’s prospectus to raise the money. The result was disappointing. A group of banks agreed to lend £50 million only if Hartwell provided a further £30 million. To Hartwell’s surprise, by May 1985 he had found only £20 million. A further £10 million was needed before the loan could be secured. Sketchy rumours about Hartwell’s plight had reached Andrew Knight before he flew to America for the Bilderberg Conference. He returned to London with the news of Black’s enthusiastic interest.

Travelling on the Tube from Heathrow airport to London, Knight was surprised to read a Times report of the Telegraph’s failure to find sufficient money. He immediately telephoned Evelyn de Rothschild. ‘I think Michael Richardson must have leaked it,’ said Rothschild. Richardson was the bank’s director responsible for raising the loan. Greedy and sly, Richardson would in later years find it difficult to prove his integrity, but in 1985 he was still trusted. ‘We need another £10 million,’ continued Rothschild, ‘and can’t find anyone.’ ‘Would any money be welcome?’ asked Knight. ‘Even from a North American?’ ‘I would see no problem,’ replied Rothschild. By the next day, Knight had received the prospectus and other reports. ‘Horrendous,’ he muttered. At the outset, Richardson had failed to warn Hartwell that £130 million would be insufficient to build the new printing plants, and had subsequently refused to seek out other reputable investors.

Excited by the news, Knight telephoned Black. The time in Toronto was 8 a.m. on Monday, 20 May, and it was Victoria Day, a public holiday. Black was asleep, and to Knight’s surprise refused to take the call until lunchtime. Knight interpreted that rebuff as an amusing idiosyncrasy rather than the lazy arrogance he would later perceive. For a fleeting moment he considered telephoning Katharine Graham, the impeccable owner of the Washington Post who would make an ideal proprietor of the Telegraph. The thought soon evaporated.

Once awake, Black rapidly understood his latest chance of taking advantage of another’s distress. ‘I’ll fax you Rothschild’s papers,’ said Knight. ‘I don’t have a fax machine here,’ replied Black. Noting his casualness, Knight sped to meet Lord Hartwell. ‘Would you be prepared to accept a Canadian investor?’ asked Knight. Trusting the emissary, Hartwell agreed to meet Black in New York. Knight was doubly delighted: first by Hartwell’s eagerness, and second by Rothschild’s failure to undertake any enquiries about Conrad Black’s reputation and probity. Unbriefed, Hartwell flew by Concorde to New York on 28 May, under the mistaken assumption that the money was being offered by Conrad Ritblat, a London property developer. Behind him in the aircraft sat his directors and Michael Richardson, uncertain of his loyalties.

Conrad Black had not yet arrived when the group entered a scruffy suite in the Hilton Hotel at Kennedy airport. Twenty minutes later, he appeared. He was struck by the Dickensian eccentricity of Hartwell and his entourage, seemingly carrying the dust and smells of olde London from which they had reluctantly taken a day’s leave. Hartwell resembled the battered Ford Cortina car in which he daily drove himself to Fleet Street. The others looked like characters from The Pickwick Papers. Sitting next to Hartwell was Black’s old friend Rupert Hambro, who had been in the plane from London. Frustratingly, Hartwell had spent the entire flight scrutinising every word of that day’s Telegraph, which prevented the banker from initiating a probing conversation. His misfortune was rectified by Richardson’s opening remarks: ‘Lord Hartwell needs an investor offering £10 million,’ said the banker, confirming the Telegraph’s plight.

Black required no advice about his tactics. His cultivated performance, concealing a burning ambition to become a media tycoon, suggested a gentle knight coming to the rescue. ‘All I have to worry about is which pocket the money’s coming from,’ he told Hartwell as he described his achievements and his limitless cash flow.

(#litres_trial_promo) There was no hint that his bankers in Toronto were demanding the repayment of loans, or that he was being publicly described in some quarters as dishonest. Nor did he reveal that he would need to borrow the £10 million he was offering Hartwell. Before committing himself, however, he wanted to tilt the odds in his favour. He and Hambro excused themselves and went for a walk, despite the heat and humidity, in the hotel garden. Hartwell, they agreed, was clearly on his last legs. The question was how to use the loan to capture ownership of the Telegraph. Knight had suggested that Black should only agree to invest £10 million in exchange for one strict condition: if Hartwell needed more money, he would be contractually bound to first ask Black, who would then become the Telegraph’s majority shareholder. ‘It could take five years before he needs the money and you get the newspaper,’ Hambro cautioned. There was, he explained, uncertainty about Britain’s newspaper industry. Eddie Shah, a printer, had provoked a bitter battle outside his premises at Warrington in Lancashire by using non-union labour. If Shah won, the trade unions’ grip over the Telegraph might be weakened, but nothing more. Neither Hambro nor Black knew that Rupert Murdoch, owner of The Times and the Sun, was building a new printing plant in Wapping, near Tower Bridge, and was secretly planning to destroy the print unions by printing all his newspapers with non-union labour. Better-informed than Hambro, Knight had estimated Hartwell’s eventual downfall within two years. Either way, the two men agreed as they returned to the suite, the opportunity was astonishing. ‘It’s a wonderful entrée,’ concluded Hambro. Black nodded. He scented blood.

Hiding his excitement in a performance that would have been worthy of an Oscar, Black formally made his offer of £10 million for 14 per cent of the Telegraph’s shares, on condition that if Hartwell needed to raise more money, Black should have the right of first refusal, and that any investment would give Black a majority shareholding in the company. At that moment Michael Richardson ought to have intervened to warn his client about the possible consequences. Instead, he remained silent. Hartwell, he had decided, was beyond saving. ‘My role,’ he would later say, ‘was to ensure the successful placement of the loan, not to care for the Berry family’s interests.’ Unprotected by Rothschild’s, Hartwell replied without fully understanding the implications of Black’s condition, ‘I don’t think, Mr Black, we can resist that.’ Convinced that he would not need more money, Hartwell agreed to gamble his empire for just £10 million.

As Black watched Concorde take off for London carrying Hartwell and his entourage, he understood the astonishing opportunity organised by Andrew Knight. He had cast the bait, the reel was running, and once the pressure slackened he would jerk the rod and wind in the line. There was a risk, but it was limited. As he returned to his plane he could reflect that only six years after the turmoil and aggression following Bud McDougald’s death, he might be about to become a legitimate media tycoon in London. The outstanding hurdle was whether Hartwell would honour his verbal agreement within a formal contract. Black entrusted the final negotiations and drafting to Dan Colson, a friend from McGill University who was now working as a lawyer in London. Colson was to ensure that the pre-emption clauses giving Black an irrefutable right to the company were watertight.

If anyone in the City or the British establishment had wanted to protect the Telegraph from a foreign predator, there was still time to do so. Black was not entirely unknown in London. In the early 1980s he had appeared at a dinner held by Charles Price III, the American ambassador, and was introduced to Tim Bell, the famous publicist who had been at the heart of organising Margaret Thatcher’s first election victory. Bell, well connected and liked, was among those needed by Black if he was to persuade the establishment in London of his wealth and honesty. Gratifyingly for Black, that was unnecessary in 1985. Although Knight was aware of Black’s reputation, he remained silent, while others did not bother to attempt to discover the truth from contacts in Canada. Unlike the protests that had greeted Rupert Murdoch’s purchase of The Times in 1981, no one in London understood or even cared about Hartwell’s fate, least of all his financial advisers. ‘Rothschild’s,’ the banker David Montagu would say, ‘handed the Berry family’s balls to Black on a silver platter.’

Hartwell’s fate was inescapably sealed on 13 June 1985. After the agreement was signed, Black’s behaviour was orchestrated by Knight. ‘Don’t say a word when the announcement is made,’ he ordered, ‘and stay in Toronto, out of sight.’ Without protest, Black obeyed. If his reputation was discussed in London, he knew, there could still be problems once Hartwell’s plight became terminal.