По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

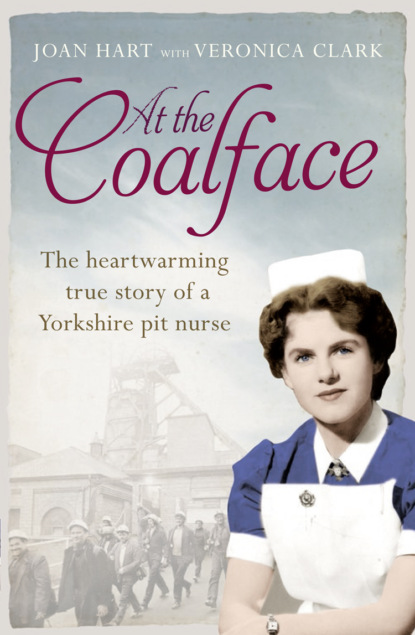

At the Coalface: The memoir of a pit nurse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Surely drinking on the job wasn’t allowed?

Then I thought of the poor man waiting for us, and the gruesome amputation. I grabbed the bottle and took a quick gulp. The brandy warmed my mouth and throat as I swallowed. I gave the hip flask back to Dr Creed, expecting him to replace the cap – only he didn’t. Instead, he held it aloft and took a quick swig too! He inhaled a huge breath of air, replaced the lid and turned to face me.

‘Better?’ he asked.

‘Better.’

And I felt it. We were just about to step into the cage when Bert came running over to find us. He’d received a call to say the miner had been freed and rescued from the rubble. His leg was barely attached but the first-aid team underground had tied a tourniquet around his thigh and strapped his legs together to keep the damaged leg stable. When the injured miner – a man called John – was brought back up to the surface, Dr Creed administered a maximum dose of morphine, and John was loaded by stretcher into the pit ambulance. I travelled with him to hospital, where I handed him over to the doctors who’d been waiting for his arrival. With nothing else to do, I travelled home, both physically and emotionally spent. I felt helpless and began to sob. I’d been taken on to care for these men but I wasn’t God and I couldn’t perform miracles.

‘It was just so awful,’ I wept. Peter wrapped his arms around me and tried his best to comfort me. ‘I just felt so helpless.’

I refused to shed a tear at work. Instead, I stored it all up inside so I could release it later at home where no one could see or hear me. I couldn’t let the men see me upset because I needed to be strong for them. I couldn’t let them see my tears because by now they trusted me to do the right thing, even when faced with a life-or-death situation. But the truth was that the responsibility often weighed me down.

John was eventually stabilised, and later that evening the hospital surgeons amputated his right leg. He was still a little woozy when I called to visit him in hospital the following morning, but he was also very accepting in spite of losing a limb.

‘I’ll be honest wi’ yer, I’d rather it hadn’t happened, Sister, but at least I’m alive, so I’ve that to be grateful for,’ he reasoned. His bravery made me want to let go of my resolve and cry.

It’d been a horrendous accident, made worse by the fact that John had initially been trapped underground, miles away from the nearest hospital. But that was the importance of my job. I was there to keep the men safe, and not only to try to help prevent accidents, but also to treat them accordingly should one occur. I was their first port of call, and together with Bert we had a responsibility to our men. There was such camaraderie among the miners that within 24 hours of John’s accident the afternoon shift had collected enough money for a state-of-the-art wheelchair. They’d collected even more to pay his wife’s wages so she could stay with him at his hospital bedside. I loved that about working at a pit – the miners were a family. The men looked out for one another in a way that most people would for their own blood. During my time as a pit nurse I became stronger because I realised I’d always have that same support too.

The automation of the pits made the mines more productive than with a man armed with just a pick and shovel. The latest machinery brought with it fewer accidents, but more danger and risk of amputation. After John’s accident, I tended to men who’d had their fingers ripped off. At first, I found it difficult because the patients would be filthy from working underground when they came to see me – hardly perfect conditions when trying to keep infection at bay. I knew I always had Bert, and a Coal Board doctor was only a phone call away, but ultimately I had to learn to trust my judgement and make the right decision.

At first I was over-cautious. If a man had a foreign object in his eye, I’d send him to hospital. Chest pains were another direct route and a ride in the pit ambulance to A&E. You could never tell if a pain in the chest was the start of a heart attack or something less sinister. I didn’t take any chances and packed them off all the same. However, there were a few miners who knew the system and tried to play me like a fiddle. Doncaster Rovers were playing a vital home game when I received a call an hour or so before kick-off, to say a man was being carried to the medical centre on a stretcher. He’d complained of severe stomach pains, and at first I’d been a little concerned. However, my father, who was the afternoon gaffer, knew the miner well. He also knew that he was an avid fan who became ill every time Rovers played at home.

‘Watch him, Joan. He’s trying to pull t’wool over yer eyes to get off work so he can go and watch t’game. He’s known for it – we all call him Sick Note.’

Sure enough, I was presented with a man who had absolutely nothing wrong with him other than a burning desire to watch his home team.

‘Where does it hurt?’ I asked as I proceeded to examine his stomach. I placed my hands flat against it, feeling for tenseness. Patients with severe stomach pains, as he professed to have, automatically tense their muscles because the last thing they want is to be examined. His stomach was soft and relaxed. I smelt a rat. The more I examined him, the more the pain seemed to move around and change direction.

‘No, Nurse, it’s more over this side,’ he wailed dramatically.

‘That’s funny. I thought you said it was over there a minute ago.’

The man stopped his crying and looked directly at me.

‘It is, I mean, it’s over there as well,’ he said, resuming his play-acting. ‘Oooh, it hurts so much, I think I need to go home to me bed.’

I knew I was being taken for a fool so I decided to give him a taste of his own medicine, or more directly, some of my own.

‘Here,’ I said, spooning out a foul concoction – a special mixture of peppermint, sal volatile (smelling salts) and kaolin. It was one I used specially on time-wasters.

The medicine was thick and white, and it tasted disgusting. I knew it wouldn’t do him any harm, only make him feel a little queasy. If he hadn’t felt sick before, he certainly would now. It seemed to do the trick because he never came to see me with stomach pains ever again.

Dad was a great source of information whenever I was in doubt. I knew I was lucky to have him there. My father was wise, firm – but fair – and he didn’t suffer fools gladly. Also, he’d never, ever ask his men to do anything he wouldn’t do himself. The miners knew this, so they respected him, and in turn they came to respect me.

One day, my father was complaining he couldn’t hear very well.

‘Must be old age,’ he grumbled, putting his index finger inside his ear, ringing it around in frustration.

‘Come over to the medical centre so I can have a proper look,’ I shouted back at him. It was true; he’d slowly become as deaf as a post.

Once inside the medical centre, I took out my auroscope – I knew what this was by now after my embarrassing newspaper débâcle – and had a proper look. I immediately knew what was wrong.

‘You’re not going deaf, Dad. It’s your ears – they’re full of coal dust. You just need to have them syringed.’

But the thought of me sticking a big needle into his ears made him reel back in his chair.

‘Whaaaat?’

I stifled a giggle.

‘Don’t worry. It’s not as painful as it sounds. I just need to pop some olive oil inside your ears for a week, and when you come back I’ll syringe it out.’

‘Will it help with my hearing?’ he asked dubiously.

‘Absolutely. When I’m done, you’ll have ears like a bat!’ I grinned, before grabbing a small bottle of olive oil and some pads of cotton wool to start the procedure.

Sure enough, he was back in the chair a week later as I syringed the muck from his ears. As soon as I’d finished a wide smile broke across his face.

‘Bluddy ’ell, Joan, it’s a miracle! I can hear everything. Tha’ sounds as clear as a bell!’

I tried not to laugh. Secretly, I was delighted my father had allowed me to treat him. But not as delighted as he’d been, because he told everyone about me and my miracle cure for deafness. At first the men had been suspicious of me and my fancy new ways, but now my father was living proof that I knew exactly what I was doing. I could and would work wonders for them too. Soon I had a queue of men at my door, all waiting for my ‘miracle treatment’.

‘I’d like you all to go and see your doctor first, get him to check your ears, ask for a note and then come back to see me.’

I needed a doctor to check the men first to ensure that they didn’t have any underlying conditions. Days later, hordes of big burly miners dropped in one by one clutching their consent forms. A week later, when the first batch of men had been successfully syringed, they told their colleagues, and so word began to spread. One day, I arrived at the medical centre to find more than twenty miners queued up outside the door. Soon there was so much demand that I had to hold a special Saturday clinic to keep up with it. I didn’t mind coming in for a few hours on my day off. The fact that I was slowly winning the trust of the men was more important to me. But it wasn’t just ears I treated. One day, I was syringing a man’s ears when he mentioned that he also had a bad back.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: