По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

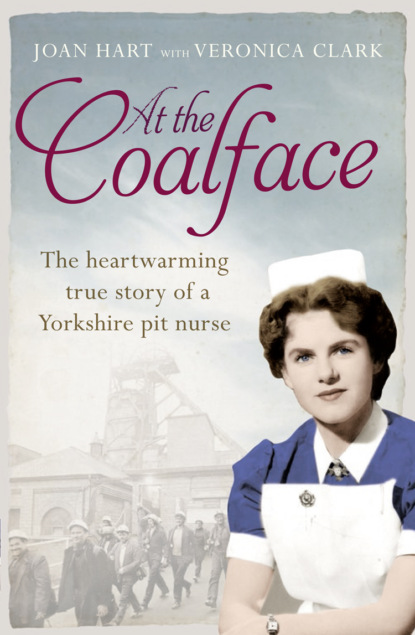

At the Coalface: The memoir of a pit nurse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We spoke long into the afternoon and then he told me something quite unexpected.

‘You do know your mother came to Doncaster looking for you after you’d left London, don’t you?’

I was astounded.

‘Yes,’ he continued, ‘she scoured all the hospitals in the area but no one had a record of a Joan Hart, so in the end she came back to London.’

Somehow, the fact that both Mum and Peter had come looking for me filled me with hope. I thought no one would have even noticed that I’d gone, but I’d been wrong.

‘I love you with all my heart,’ I said, taking his hand in mine.

‘Me too, Joan, me too.’

Dad was relieved when we told him we’d made up. But first, Peter had to return down south to serve his notice. In a way it made things easier because it gave me time to find us a suitable house to live in.

‘I think I can help you there,’ Harry, my step-brother, said.

Harry was Polly’s eldest son. He was a successful businessman who owned four busy shops, so he mixed in high circles. One of his acquaintances was a flying officer in the RAF who owned a house he was looking to rent out in a place called Balby, situated on the outskirts of Doncaster. The house, on Stanley Street, sounded charming by description, but if I’d imagined a palatial home then I was sorely mistaken. The two up, two down was a complete tip! To make matters worse, the walls rattled every time a train went past on the main line, which ran along the bottom of the garden right beside the outside loo! Still, with little else available, we took it – beggars can’t be choosers. Thankfully, Tony and Ann offered to help clean it.

‘Don’t worry, Joan. We’ll soon have it sorted!’ Ann said breezily, rolling up her sleeves. I admired her optimism.

There were so many empty beer bottles stashed under the sink and in various hidey-holes around the house that, by the time we’d collected and returned them all to the off-licence – or beer-off, as we called it – we’d earned ourselves £5! The previous tenant, it seemed, had been partial to a drink or three. The house was freezing cold, but thankfully it had a fireplace in the living room, which doubled up as the dining room. Ann would cart huge carrier bags of coal over to me from home, travelling all the way on the bus from Woodlands, because Dad got it for free. It was a good 8 miles away, so her arms always felt a little longer by the time she arrived. I couldn’t have cleaned it without her and Tony because it was the dirtiest place I’d ever seen – even Elsie would have flinched. We discovered some strange things, but the strangest and most interesting find came right at the end, when we tackled the basement.

‘Here, look what I’ve found,’ Tony called as I squinted in the dim light. I could just make him out – he was holding something in the air, high up above his head. He started clacking them with his fingers. At first I thought they were a pair of castanets, but as Ann and I got closer we realised it was a pair of false teeth! Ann screamed the house down, but I fell about laughing and so did Tony. It was nice to laugh; otherwise I think I might have cried. Still, we did what we could with the rest of the house. Ann and I bought metres of red gingham checked material from Doncaster market so that we could make curtains. We hung them up in the kitchen window, and strung them on a piece of elastic in a ‘skirt’ around the bottom of the big white butler’s sink.

Peter visited whenever he could to help out, but without a car he had to catch the train. It was such a long journey that half the weekend was taken up by travel alone. Peter also needed to find himself a job. True to his word, Dad had heard of a position at Brodsworth Colliery. He put Peter’s name forward and helped set him on his way.

‘It’s hard graft, mind you,’ he said, sizing Peter up. I could tell he was wondering if my southern husband was up to the job.

Peter took it, but four weeks later Dad’s north–south prejudice was confirmed when Peter was laid off sick with a sprained back. He was a highly skilled plumber, so he wasn’t used to digging or hard labour to earn a living.

With a house to move into, I gave my notice at the nursing home and secured a better position as Deputy Matron at a day nursery that cared for babies and children aged from a few months old up to two years. The nursery was different to others in the area in that it was used by a lot of one-parent families, which was something I identified with. The matron was an unmarried mother with a little boy who attended the same nursery. I admired her because this was a time when many mothers were so shamed by having a baby out of wedlock that they’d simply abandon them or give them up for adoption, but not this lady. She was incredible, and I had nothing but the utmost respect for how she loved and cared for her little boy.

The working hours were almost as gruelling as the nursing home. When I arrived at 6 a.m., I’d find half a dozen prams already lined up and waiting outside the main door. The parents would’ve gone, usually straight off to work. There was no worry or concern back then that someone might steal a baby, because everyone did the same thing. Mind you, it was also a blissful time when you could leave your front door unlocked without fear of being burgled or murdered in your bed. If I was shocked by the babies being left in the morning, then I was even more surprised when the same parents forgot to pick them up at night. More often than not there was usually a mix-up or breakdown in communication. One parent would presume a friend or relative was picking the child up and vice versa. A lot of the parents were bus drivers or conductors working long shifts, so I’d have to ring Doncaster police station to get them to trace the missing mum or dad.

‘Hello, its Elmfield nursery. I’m afraid we’ve got another no-show,’ I told the officer on the other end of the phone.

‘Another one?’ he gasped. ‘How on earth can you forget to pick up your child?’ The line went silent for a moment and I visualised the officer shaking his head in despair. ‘Don’t worry; someone will be along shortly.’

Whenever I had a situation like that, Peter would sit and wait with me until the police officer arrived. The officer would try to track down the parent, who always had a valid excuse, but they’d still be given a police caution.

I loved working with the children, and I often imagined myself as a mother with a brood of my own. All the same, it was nice to hand them back at the end of the day and switch off. I’d worked at the nursery for almost a year when Dad called to see me. He’d heard of a new job at Brodsworth Colliery.

‘They’re looking to set up a new medical centre, so they need a fully qualified nursing officer. I’ve put your name forward. Hope that’s all right?’

It was, because by now I knew it was time to move on, although it didn’t stop the nerves rising inside my stomach. I was still in my early twenties – in many ways I was still learning – yet at the pit I knew I’d be in charge of thousands of men. I’d always been confident in my own nursing world of hospitals and sterile wards, but this was a different type of nursing – this was industrial nursing, which I’d never done before. But I wasn’t proud. I’d ask for help if I needed it.

Although I realised it’d be a whole different ball game, I trusted my father and his judgement. Ultimately, I knew he wouldn’t have recommended me if he didn’t think I was up to the job.

5

A Miner’s Nurse (#ufa4c5668-c4b9-5095-a361-ebfb2e0f45bd)

I was a complete first and a bit of a curiosity at Brodsworth Colliery – a female nursing officer in charge of 3,000 men – but the National Coal Board was trying to improve its safety record after the pits had been nationalised nine years previously. Now that I’d been hired, the health of the Brodsworth miners was down to me. I’d work in a preventative role as well as being there to treat the men.

Before I’d arrived, the miners relied on a bloke called Bert, a tall, slim and authoritative man in his mid-forties. He’d been at the pit for donkeys’ years and was a trained first aider. He was also the man you went to in an emergency. It was 1956, and Bert was so trusted and highly respected that all the people in the village would call on him rather than use a doctor. To be honest, I didn’t blame them because what Bert didn’t know wasn’t really worth knowing. His office was an old wooden hut situated by the shaft side. The hut was cramped and dark and as far removed from sterile hospital wards as you could get. Nevertheless, Bert, who had a mop of thick, dark, curly hair, would expertly bandage and generally patch the men up in the dim light and dusty surroundings. If it was a serious injury then he’d pack them off to the hospital, or call for one of the Coal Board doctors, but Bert was always the miners’ first port of call in an emergency.

He was also very obstinate and viewed me, just 24 and a mere slip of a girl, with extreme suspicion. He resented the fact that I was heading up the brand new medical centre, because his male ego wouldn’t allow him to accept orders from a young lass. The centre was being built specially but he disliked the idea so much that he refused to come out of his hut even to take a look at it. I’m sure the curiosity must have killed him, but he was a stubborn old goat and he refused to budge an inch. Despite this, I looked up to Bert because he was so knowledgeable.

I’d been brought up in Woodlands, the village attached to Brodsworth Colliery, and my father – Harry Smith to everyone else – was a senior official there. Dad was respected, and everyone knew I was his eldest daughter. By this time, my brother Tony had started at Brodsworth as a trainee cadet, so the men called me either ‘Harry Smith’s eldest’ or ‘Tony Smith’s sister’. I was never called by my actual name, despite my protests. Sometimes the men couldn’t even be bothered to refer to me by the family name, and instead called me ‘the head girl from Woodlands school’. I’d come off the hospital wards and never done industrial nursing before, so I was also a little intimidated by the miners and my surroundings. The medical centre was still being built, so I got to choose the colour scheme.

‘I think I’d like a nice canary yellow,’ I said as I surveyed the plans. The man was horrified and his mouth fell open as though I’d asked him to paint it candy pink. To say the men on site were appalled by my choice of colour would be an understatement.

‘Yellow!’ one of the miners shrieked, shaking his head in dismay. ‘But we normally have navy blue on the walls.’

I turned to face him. I was only young and I knew I was a woman working in a man’s world, but I was also very determined.

‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘And navy blue is a horrible, dark colour. I need it to be light and welcoming, so I’d like it painting yellow, please.’

I nodded my head as though that was my final word on the matter. Despite many objections, my wish was eventually granted, much to Bert’s disapproval. I’d not consulted him, but I could just imagine him sitting over in his dreary dark wooden cabin, rolling his eyes in despair. As soon as the medical centre opened, I realised it was going to be hard to win the men over because, instead of coming to me, they continued to consult Bert. Now it was a battle of wills.

‘Have you heard? She’s only gone and painted it bloody yellow!’ one of the men grumbled as he passed by my window early one morning.

I was up and running, but with no patients to treat and yellow walls to boot, I knew I had my work cut out. The medical centre held all the latest equipment, including a state-of-the-art steriliser, but try as I might, I couldn’t get Bert or his team of first-aiders through the door. And then fate intervened. One day, I stretched over the autoclave – the device used to sterilise equipment to a very high temperature – when I caught my right arm against it. The burn was painful because it was deep and it had penetrated through several layers of skin. Also, because it was my right arm, it was impossible for me to dress with a bandage. With no one else to turn to, I walked across the pit yard towards Bert’s hut. I tapped lightly on the door. As he opened it, I could tell he was shocked to find me standing there. He also seemed a little suspicious, as though I was trying to trick him.

‘Sorry to bother you, Bert,’ I began, ‘but I wondered if you could take a look at my arm, please? I caught it on the autoclave. It’s really painful and it’s my right arm … I can’t dress it properly.’

I was so busy trying to explain that I hadn’t noticed that Bert had left the door ajar and had sat back down. I took it as a signal to go inside.

‘Tha needs to be more careful,’ he grunted as he pulled out a roll of bandage from a nearby drawer. He expertly dressed my wound as his dark curly hair flopped around his face, hiding his expression.

‘I’m really grateful, Bert.I don’t know what I’d have done without you.’

He looked up at me and nodded, but he was a hard man to read and I wondered if he thought I’d burned my arm on purpose. I hadn’t, of course, and it was painful all the same. I winced as he tied the bandage, and he nodded to indicate that he’d finished. I wasn’t quite sure what to do so I stood up and turned to leave. As I did, Bert spoke.

‘It’s a nasty wound, that is. Tha better come back tomorrow so I can change t’dressing.’

I turned and smiled gratefully.

‘Thanks, Bert. I really appreciate it.’ And I did. I also saw a chink of light. Maybe Bert wasn’t such a tough nut to crack after all.

The following day I went back to have my dressing changed, and the day after, until soon I’d visited Bert for the best part of the week. Early one morning, I was told an official would be visiting the medical centre. I asked Bert if he could come over to me instead, but he wasn’t keen. He’d already made it plain that he didn’t approve of me or my canary-yellow walls.

‘Please, Bert. I’ll get into trouble if I’m over here with you and not over there,’ I said, pointing at the medical centre. ‘It’ll only take a minute, and then you can leave.’

After much deliberation, Bert decided that he would indeed come over to dress my wound. I think a small part of him really wanted to see the inside of the centre, but his male ego wouldn’t let him cross the threshold without good reason. Of course, Bert changed my dressing to his usual high standard. As he packed up to leave, I took a chance.

‘While you’re here I may as well show you around.’