По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

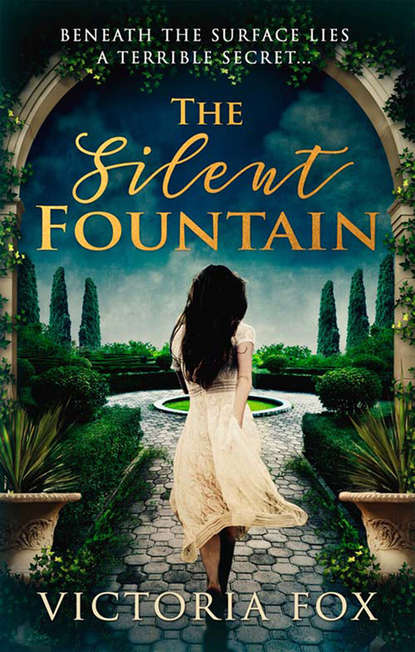

The Silent Fountain

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_0d2dcee7-335c-5b90-875f-fcd140541378)

London

One month earlier

They say you can never love again like you love the first time. Maybe it’s the heart changing shape, unable to resume its original form. Maybe it’s the highs made more acute for their novelty and strangeness. Or maybe it’s the soul that grows wise. It learns that the risks aren’t worth taking. It learns to hurt, and in doing so protect itself.

There is consolation in this, I think, as I thread through the crowds on the Underground – commuters in rush hour, plugged into their phones; tourists checking maps and getting stuck by the ticket machines; couples kissing on the escalators – the certainty that whatever happens, wherever I end up, I will never again go through what I have been through before. We are shepherded from the Northern Line up into fresh air, where the blare and hum of the city bleeds past in myriad lights and colour. I pass a group of girls heading out for the night; they must be my age, I suppose, late twenties, but the gulf between us is yawning. I look at them as if through a window, remembering when I was like them, frivolous, carefree, naïve – how it feels to stand on the brink of the world, no mistakes made, at least none so irrevocable as mine.

One thing I love about London is the anonymity. So many people and so many lives, and it’s an irony that I came here to be noticed, to be someone, yet it was at the centre of everything that I achieved invisibility. I will miss the anonymity, when they find out. I will look back on it as a cherished prize, never to be regained once lost.

I catch the bus, staring out of the window at rapidly darkening streets. Across the aisle a guy in glasses reads the Metro, its front page belting the headline: MURDERER HELD: COPS CATCH CAR BOOT KILLER. I shiver. Will I earn my own headline, one day soon? What will they say about me? I see my name, plain old Lucy Whittaker, in the round, friendly handwriting that as a child adorned my homework, my thank you letters, the birthday cards I wrote to my friends, then latterly the typed headers on my job applications, become all at once horrid and threatening, a name to be appalled by. People I once knew will say, ‘Not that Lucy Whittaker? But she’s far too quiet, far too shy, she wouldn’t do anything like that…’

But I did, I think. I did do something like that.

We come to my stop and I step out into the evening, wrapping my coat tight as the wind picks up. I keep my head down, the plastic box clamped under my arm.

My phone beeps. For a stupid moment I think it’s him, and I despise myself for how swiftly I dive into my pocket, hand trembling and hope sinking as I realise it’s not. It’s Bill, my flatmate. Belinda’s her name, but she never liked it.

When are you home? I have wine Xxx

I’m almost there so it isn’t worth replying. My walk slows. As ever when I open my messages I find my eyes drawn to his, our chains of all-night conversations, flirty, thrilling, the way my heart danced every time that screen lit up at two in the morning. I should delete them, but I can’t. It’s as if wiping them will erase any proof that it happened in the first place. That before the bad, there was good. There was, before. It was good. What happened, there was a reason for it…

Don’t be an idiot. There is no reason. Nothing justifies what you did.

And of course he wouldn’t be in touch. He’d never be in touch. It was over.

I turn on to our street. Unlocking the front door, I see Bill still hasn’t got the hang of sorting through the post, so I scoop the scattered envelopes off the floor and divide them between the flats, before taking our own upstairs. Bill still hasn’t got the hang of a lot of shared living, I’ve noticed, like replacing loo roll or putting out the recycling every once in a while. I don’t mind, though. She’s been my best friend since we could walk; she’s been with me through it all and she’s still with me now, the only one who knows the brutal truth and even then she didn’t walk away, when she really could have. When she should have. That’s why I don’t care about the recycling.

‘How was it?’ She’s waiting when I go in, drink poured, TV on, some rehash of a talent show, and she drains the volume when I lift my shoulders.

‘As expected.’ I set the box down and consider, as I had back at the office, how five years can be compressed into five minutes’ packing. Some old notecards, my desk calendar, a sangria-bottle fridge magnet from Portugal sent to me by a client.

‘No fanfare, then?’ Bill gives me a hug and a squeeze. The squeeze brings up tears but I blink them away. ‘It’s your own fault,’ Natasha, his deputy, had hissed, as I’d slunk towards the exit of Calloway & Cooper, trying to ignore the stares that followed, fascinated and horrified, like traffic crawling past a pile-up.

Natasha has had it in for me from day one. My theory? She’s in love with him. As his Commercial Director she was widely regarded as his second in command – but then I came along, usurping her as the closest person to him, his PA, and I know she tried to get someone else into the role because Holly in Accounts told me. Only, Natasha didn’t win. I did. And I think she couldn’t handle the fact that, for a second there, towards the end, before it all went wrong, it looked as if he might have loved me back. When it blew up, all her Christmases came at once. Natasha was delighted to see me go, and couldn’t believe her luck at the circumstances that drove me to it.

I try a laugh but it dies in my throat. ‘No fanfare,’ I agree, and grab the wine and sink it in one. Bill refills me. I want to smoke a cigarette, but I’m trying to give up. Great timing, Lucy, I think. Who cares now, if you live or die? But that is melodrama, and I annoy myself for thinking it. Instead, I keep focused on the alcohol. If I keep drinking, I’ll get numb, and if I get numb, I won’t feel anything. I won’t feel his touch on my cheek, his kiss on my mouth, my neck…

‘Come on,’ says Bill, with an uncertain smile. ‘It’s finished.’

‘Is it?’

‘You never have to see those people again. You never have to see him again.’

One thing Bill doesn’t understand, and I can’t find the words to explain: I have to see him again. Even after everything, how I should want to run as far away from him as I can, I’m as addicted to him as I was the first day. Inappropriate isn’t the half of it. I read that the funeral happened this morning, in a cemetery south of the river, and I can’t stop thinking of him, rigid with grief, those grey, beautiful eyes set hard on the ground, the cool drizzle settling on the shoulders of his coat, a coat I’d once warmed my hands in on a cold night on Tower Bridge, and he’d kissed the tip of my nose. How I long to put my arms around him now, tell him I am sorry and that I miss him. When what I should be feeling is guilt, burning guilt, shame and disgrace and all those things, and I do feel them, every day I do, but at the same time I can’t forget the power of us. We don’t belong with any of that confusion or chaos or sadness.

‘…You could consider it, you know, if that’s what you want.’

Bill is looking at me gently, waiting for a response.

‘What? I was miles away.’

‘Freddy’s sister’s boyfriend,’ she says, presumably for the second time. ‘He’s just come back from Italy – that language course he went on in Florence?’ Bill prompts me and to placate her I nod, even though I have no memory of this (so much over the last twelve months has dissolved to insignificance; I can’t even remember who Freddy is – someone Bill works with?). ‘While he was out there,’ she goes on, ‘he made friends with this girl who was looking after a house on weekends. Well, I say house, but it’s more like a mansion. In fact Freddy said it was this giant pile, and someone famous lives there but the friend never met her, and anyway, this woman’s a recluse and never goes out.’ Bill slumps down on the sofa. ‘Sounds intriguing, right? Like the start of a novel.’ There’s something behind the cushion and she reaches to retrieve it. ‘Hey,’ her face lights up, ‘I found 50p!’

I frown. ‘What’s this got to do with me?’

Bill crosses her legs. ‘The girl got fired and they’re looking for someone to replace her. All very hush-hush… apparently they’d never advertise. The woman sounds a bit weird, sure, but how hard could it be? Dusting a few shelves, sweeping the floor…’ She makes a face and I wonder if her knowledge of looking after a house extends beyond Cinderella. ‘Then getting to sunbathe all day with some sexy Italian you’ve met in the city? I’d do it myself if I didn’t have to go to work on Monday.’

I’m wary. ‘What are you suggesting?’

‘Think about it, Lucy.’ Her voice softens. ‘Since this thing happened, you’ve been desperate to get away. You haven’t stopped talking about it, how you can’t stay here. Look,’ she says, standing, ‘I want to show you something.’ She steers me to the mirror in the hall. ‘Tell me what you see,’ she says. ‘Honestly.’

It doesn’t help that strewn across the wall are pictures from the days before. Nights out with Bill, holidays with friends, a bungee jump I did on my twenty-fifth birthday, after I finally broke free from home and started building a future for myself. That’s how I see it, this looming punctuation mark in the story of my life, isolating the years preceding him and the lonely days after, creeping into weeks, and I was a different girl then: bright, hopeful, lucky, alive. What do I see now? A dull ache in my eyes, my skin wan with nights spent thinking and wondering and turning over what ifs, hollowness in my cheeks, and sadness, mostly sadness.

‘I don’t want to do this,’ I say, shrugging free.

‘You’re not you, Lucy. This isn’t you.’

‘What do you expect?’ I round on her, not keen on starting a fight but unable to help it. I need to shout at someone, to be angry, because I’m sick of being angry with myself. ‘Her funeral was today – did you know that? And I’m supposed to leave everything behind, the mess I’ve made, and swan off to Italy for a holiday?’

‘It’s not a holiday,’ says Bill, ‘it’s a job. And, let’s face it, you need one.’

‘I’ll manage.’

‘What about the press?’ She’s silenced me now. ‘What about when they’re blowing up your phone, or when they’re smashing down the door and you’re afraid to go outside? Do you think he’s going to defend you, then? He doesn’t care, Lucy – he doesn’t give a crap about you. He’ll put it all on you and then how’s it going to look?’

‘Don’t say those things about him.’

‘Fine, we won’t go there. You know how I feel. My point is: this is your chance. I mean, talk about timing! You could leave it all, come back once it’s settled.’

‘How’s it getting settled?’

‘It will. Everything fades eventually.’

I snort. But my back is to her, so she can’t see my face.

‘What’s the alternative?’ Bill asks.

I think about the alternative. Fronting the world, my family, my face splashed across the nation’s papers, quotes taken out of context, painted to be someone I’m not.

Would he break his silence then? Would he reach to help me; would he stand at my side? Bill’s words sting: He doesn’t care. He doesn’t give a crap about you.

Her question hangs unanswered. It’s all I can do to turn to my friend, the fight gone out of me. ‘I’m sorry,’ I say, meaning it, and she shakes her head like it doesn’t matter. ‘I just…’ A well swims up my chest, threatening to spill over, and my voice goes funny. ‘I’m just not coping.’

‘I know.’ Bill hugs me. ‘Please promise me you’ll consider it?’

In bed that night, I do. Lying awake, pretending to myself that I’m not waiting for my phone to light up, I listen to the passing hum of traffic that gradually dwindles to quiet, before, at around two, I finally fall asleep. The last thing I think of, for the first time in months, isn’t him. It’s a house, surrounded by cypress trees, deep in the middle of the Italian hills. As I walk towards dreams, I’m in a tangled rose garden. Something unseen beckons me, a shadow slipping in and out of sunlight.