По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

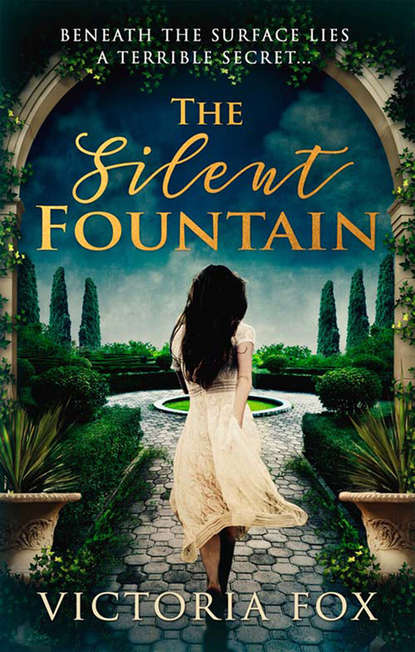

The Silent Fountain

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We embark up a grand staircase, burned-amber sandstone with an ornate banister, where we pass a series of portraits. ‘Who’s that?’ I ask, forgetting Adalina’s warning, transfixed as I am by the image of a man wearing a red blazer. One of his eyes is black and the other is green. He is standing against an emerald forest and the light of mischief dances in his stare, a light so convincingly caught on the canvas that I’m certain in the real world he is dead. Adalina watches me sideways.

‘We are in the process of covering these up,’ she says carefully, and beyond I spy several further frames draped in dustsheets. Reluctant, I follow her. Off the first landing, she shows me a series of bedrooms, unused but all the same needing care. One houses two rows of wooden sleigh beds, hospital-like, intended for children.

‘It was a sanatorium, last century,’ explains Adalina, a little too quickly.

The first thing I’ll do is air the rooms, I think, making a note of tasks I can begin in the morning. I’ve decided quickly that this is not a place in which I can allow myself to grow idle – partly because that road leads to him, and partly because I’m already resisting temptation to tease open drawers, to explore inside cabinets, to force rusted locks… to fling pale shrouds off portraits and read the names beneath.

The upper three floors are the same. There’s an old library, books caked in powder with spines cracked, and a mezzanine looking out over the garden. I want to climb up but Adalina tells me the steps are dangerous. ‘They haven’t been used in years.’ There are dressing rooms, reading rooms, water closets; pantries, larders and butteries; boudoirs and cabinets, storerooms, undercrofts and cellars; spaces left empty and who knows what they were once used for. The whole impression is one of a labyrinth, winding and never-ending, deliberately confusing where one space resonates almost exactly another. If I were alone, I’d already be lost.

We come to a door at the end of a corridor, and stop.

‘This leads to the attic,’ I say, and take the wooden handle in my palm, as if I’m testing it, as if Adalina might be wrong and it will swing open unaided. It doesn’t.

‘Nobody goes,’ confirms Adalina, and I understand this is the out-of-bounds top floor. ‘Your work extends to this point,’ she says, ‘and not beyond.’

I take my hand away.

‘I tell you this because of the girl we let go before you,’ says Adalina. ‘She did not heed my advice and Signora had no choice but to dismiss her.’

‘Will I meet her?’ I ask, and it hits me then that no one has told me her name. She. Her. Signora. The woman of the house…

‘Soon.’ Adalina’s gaze flits away. ‘For now I will show you your quarters.’

*

The Lilac Room, as it turns out, isn’t lilac at all. It is painted cream, with high, corniced ceilings and a four-poster bed swathed in thick red fabric. Crudely painted olive trees adorn one wall, just above the skirting, drawn, I’d wager, by a child.

Adalina wasn’t lying when she described this as my quarters, for, like the rest of the Barbarossa, it’s extensive. There is an adjoining bathroom, a little rundown but I’m not about to complain (I don’t relish the thought of getting lost out there in the middle of the night in pursuit of the loo), a writing desk, a couple of armchairs by a handsome fireplace (a peep up the flue tells me it’s long been blocked) and a mahogany wardrobe several times the size of the one Bill and I share back in London. Below the window, whose panes reach to twice my height, is an embroidered chaise.

Alone now, I can appreciate the full spread of the estate. Once upon a time the lawns would have been neatly landscaped, descending in tiers separated by stone to a pink- and peach-strewn rose garden, but the steps now leak into each other, the walls peeling and draped in vines, the grass overgrown. Beyond the roses, light catches on glass, where an old greenhouse is bursting with plants, and etched into a screen of brick I detect the subtle outline of a door. It reminds me of a book I read as a child, or maybe Mum read it to me, because the memory is accompanied by the mellow tang of cloves, but then I realise the window is ajar and it could just as easily be the cluster of herbs whose scent swims in on the breeze. I want to step outside and go towards that door and turn the rusted key. You will know if you trespass.

Further still, the lemon groves and the track I came in on, and, to the west, where the sun is gently setting and flooding the sky with orange and gold, there is a pergola, majestic on its mound of grass, as perfect as the curve on a paperweight. Against the bloodshot sky, twin swifts dip and dive their dusk-hour acrobatics.

There is one thing I’m omitting from this view, the thing I came past earlier and that I’m reluctant even now to acknowledge. The fountain by the entrance, set amid a dozen cypress trees, appears gloomier now the sun has fallen. I don’t know why it’s such a horrible thing. The protruding shape I detected earlier is an ugly stone fish, eyes bloated, scales crusted, its open mouth gasping air, fossilised mid-leap as if cast under a terrible spell. The trees don’t help either, standing guard, their spears raised – and perhaps that’s all it is, the notion that there is something cosseted within that requires protection, something beyond the decaying stone and stagnant water…

I turn away and fumble in my bag for my phone. There is a message from Bill, asking if I got here OK, but I must have picked it up in the city and then gone out of signal, for there’s no reception here at all. The thought of asking after Wi-Fi is anachronistic. Back at home, I’d have panicked at being off radar, but here it seems natural. Nobody except Bill knows where I am. Nobody can find me. I think of the bomb waiting to detonate in London – Natasha triumphantly handing my name to whoever’s interested, whoever wants to destroy it – and it seems impossibly far away.

Only when I lie on the bed and close my eyes does it occur to me that no contact means no him. What if he needs me? What if he has to get in touch, and can’t? I reassure myself with a plan to get connected in the city: soon, soon.

In the meantime, there is a pinch of pleasure in the thought, however unlikely, that he might be trying to reach me, that he might be the one seeking me out, instead of my repeatedly glimpsing a screen that gives me nothing. For once, I’m unavailable.

I’m gone. Nobody can catch me.

In minutes, I’m asleep.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_491ea532-e5b9-5d27-8ad7-9d317d1227be)

‘Vivien?’

The maid knocks gently then steps inside. It’s rare that Adalina addresses her by her name, and Vivien knows it is because they are about to share a confidence.

‘What is she like?’ Vivien asks. It isn’t what she really wants to ask, but she cannot ask that yet. It will seem too desperate, too close to the bone.

‘As we expected,’ says Adalina. ‘She’ll be fine.’

‘You told her…?’ Vivien glances away. ‘How much did you tell her?’

‘I told her nothing.’

Vivien exhales. Adalina lays down a supper tray, soup and crackers, a bunch of grapes the colour of bruises, but she has no appetite.

‘Are you all right, signora?’

‘I saw her from the window,’ Vivien says, daring to meet Adalina’s eye, wanting to know if the maid has seen it too. But Adalina gives nothing away.

‘Do you think she looks like…?’ Vivien swallows. She cannot say the name. ‘I saw her and I thought what a remarkable resemblance she has to—’

‘She’s dark. That is where it ends,’ says Adalina.

‘But her height, her build, everything – it’s everything.’

‘Not at all.’ Adalina protests, unwilling to give her charge any scope for indulgence. Vivien notices this, and seizes it as proof of her agreement.

‘You can’t deny it.’

‘I can. Up close she is entirely different.’

‘It was like seeing her again.’ The ‘her’ is spat like venom. It’s been years – years – but the poison remains. She cannot get her mouth around it, the taste bitter, too horrible, too immediate, all that hate multiplying inside her with nowhere to go.

‘Then you must meet the girl,’ says Adalina. ‘I will arrange it.’

‘I cannot have her living here if you are wrong.’ Vivien is trembling, her voice skittish, her heart leaden. Get control of yourself, she thinks, aware the resemblance the girl has is impossible, a trick of her mind, but the uncanny is all around, in the windows, in the water, in shadows and reflections, and she would not put it past the house to test her in this way. Vivien has heard the noises late at night, the creak of a floorboard, the slam of a door, the howl of the wind so like a woman’s scream…

‘You must eat,’ says Adalina. The pills come out, the tray set down.

Without warning, Vivien takes her hand. Adalina is surprised.

‘It isn’t her, is it?’ she asks in a strange, disembodied voice.

‘Of course not, signora.’

‘That would be impossible.’

‘Absolutely.’

‘She wouldn’t come back for me, would she?’

Adalina is frightened now.