По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

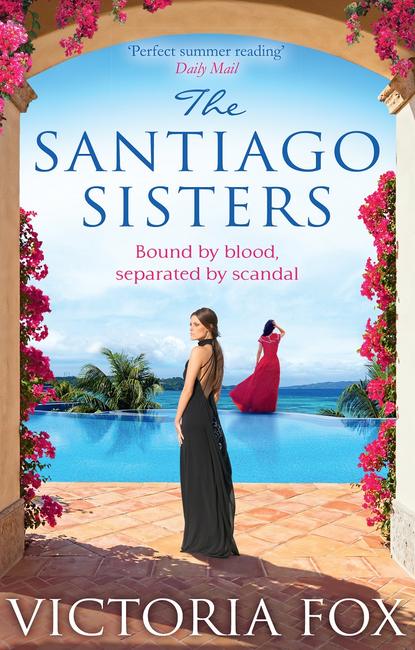

The Santiago Sisters

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Every day the sisters went riding with their father, while Julia stayed at home. It had been that way since time began. Their mother rarely emerged and the girls knew not to make noise in that part of the ranch, especially when Julia was resting.

Calida tried not to feel sad at how, on Julia’s better days, she would invite Teresita into her bedroom; Calida would listen at the door, shut out of their exchange, desperate to hear and be part of the confidence, until she heard her papa’s tread and shame directed her away. Julia spent hours brushing Teresita’s ebony hair and singing her songs, telling her stories of the past and stories of the future, assuring her what a magical woman she was destined to become. Her mama adored Teresita, because Teresita was beautiful. The twins’ division was responsible for this injustice, marking their physical difference: Teresita as exquisite and Calida as average. Calida knew there were greater things in life than beauty, but still it hurt. She wasn’t special, or in any way extraordinary, like her sister. If she were, her mama would love her more.

Once upon a time, when Julia had first been married, she herself had been a magical woman. Calida had seen the evidence, photographs her father had taken when they had worked the land as a couple: Julia against the melting orange sunset, her head turned gently away and her hair in a thick plait down her back. The horse’s tail had been frozen in time, a blur when it had swished away flies. Calida loved those pictures. This was a woman she had never known. She longed to ask her mama about that time, and what was so different now, but she was afraid of making Julia angry.

Julia told Teresita those things, anyway. At least she was telling someone.

Summer 1995 was unbreakingly hot. Sunshine spilled through open doors, the heat bouncing off wood-panelled walls. The twins were in the kitchen, paper pads balanced on their knees. Their home tutor was a harsh-looking woman called Señorita Gonzalez. Gonzalez was thirty-something, which seemed ancient, and the way she wore her hair all scraped back from a high forehead and her glasses on the end of her nose only made her more alarming. She wore heavy black boots whose tops didn’t quite reach the hem of her sludge-coloured skirt, so that a thin strip of leg could be seen in between. In classes, Teresita would giggle at the black hairs they spied lurking there, and Calida had to tell her to shut up before they got told off. Gonzalez was strict, and wasn’t afraid to use their father’s riding switch if the occasion arose.

‘I’m hot,’ said Teresita, kicking the floor in that way she knew drove Señorita Gonzalez mad. Calida’s own legs were stuck to the wooden chair, and when she adjusted position the skin peeled away with a damp, thick sound.

‘Díos mio, cállate!’ hawked Gonzalez, scribbling on the board. ‘All you do is moan, Teresa!’ It was only the family who called her Teresita: it meant ‘little Teresa’.

Teresita stuck her tongue out. Since the teacher’s back was turned, this failed to have the desired effect, so she tore off a sheet of paper, balled it up and tossed it at Gonzalez, nudging Calida as she did so, to include her in the game. But Calida didn’t like to stir up trouble. The woman froze. Calida gripped the seat of her chair.

‘You little—!’ Gonzalez stormed, blazing down the kitchen towards them, whereupon she grabbed Teresita’s hair and hauled her up, making her scream.

‘Ow! Ow!’

‘Stop it!’ Calida begged. ‘You’re hurting her!’

‘I’ll show you what hurts, you disrespectful child!’

Gonzalez dragged Teresita up to the cast-iron stove and launched her across the top of it. ‘That hot enough for you?’ she spat. Calida felt the impact as sorely as if she were the one being assaulted: Teresita’s pain was her pain. But her sister stayed silent, contained, her dark eyes hard as jewels and the only giveaway to her panic the lock of black hair that hovered next to her parted lips, blown away then in, away then in, flickering with every breath. Gonzalez took the riding switch from behind her desk and drew it sharply into the air. ‘Time for a lesson you’ll really remember!’

‘Wait!’ Calida leaped up. ‘It was me. I threw the paper. It was me.’

There was a moment of silence. Gonzalez looked between the twins. Calida rushed to her sister’s side and shielded her, just as the kitchen door opened.

‘What is going on in here?’

Diego stood, his arms folded, surveying the scene. Calida felt Teresita squirm free, but not before she took Calida’s fingers in her own and squeezed them tight.

‘The girls fell down …’ Gonzalez explained, in a different voice to the one she used with them: softer, sweeter, with an edge of something Calida was too young to classify but that seemed to promise a favour, or a reward. ‘You know how energetic they are, rushing about … Honestly, Señor, I have my back turned for one minute!’

Diego approached and ruffled Calida’s hair. ‘There, there, chica.’

Calida clung to her father. She inhaled his warm soil scent. Diego held his other arm out to Teresita, but Teresita watched him and stayed where she was.

‘Nobody’s hurt?’ he asked.

‘Nobody’s hurt,’ confirmed Gonzalez. She narrowed her eyes at Calida and Calida thought: We’re stronger than you. There are two of us. You can’t fight that.

Winter came, and with it the rains. Teresita was staring out of the window; mists from the mountains pooled at their door and the freezing-cold fog was sparkling white. The reaching poplars that bordered the farm were naked brown in the whistling wind, and the lavender gardens, once scented, were bare: summer’s ghosts.

‘What are you thinking about?’ asked Calida, coming to sit with her. Teresita always had her head in some faraway place, where Calida couldn’t follow. She was forever making up stories she would sigh to her sister at bedtime, some that made her laugh and others that made her cry. Now Teresita reached to take her arm, looping her own through it, a ribbon strong as rope, and rested her head on her shoulder.

‘The future,’ she said.

‘What about it?’

‘The world … People. Places. What life is like away from here.’

A nameless fear snaked up Calida’s spine. Privately, the thought of leaving the ranch, now or ever, made her afraid. The estancia was their haven, all she needed and all she cherished, by day a golden-hued wilderness and at night a sky bursting with so many stars that you could count to a thousand and forget where you started.

‘But this is our home,’ Calida said.

‘Yes. Maybe. It can’t be everything, though—can it?’

‘What about me?’

‘You’ll come too.’

It was another dream, another fantasy. Teresita would never leave. They were happy here, happy and safe, and Calida comforted herself with this thought every night, locking it up and swallowing the key, until finally she could fall asleep.

2 (#ulink_3262f26a-4b88-5234-adeb-c3d8d5ec4b96)

Teresa Santiago would often think of her twelfth birthday as the day she left her childhood behind. This was for two reasons. The first was the bomb that exploded halfway across the world that same day in March, in a place called Jerusalem. They heard about it on the crackly television Diego kept in the barn, a small, black box with a twisted aerial that they had to hit whenever the reception went. Teresa tried to grasp what was happening—the flickering news footage, the exploded civilian bus, the hundreds of swarming, panicking faces. It seemed like it belonged on another planet. She felt helpless, unable to do anything but watch.

‘It’s a long way away,’ reassured Calida. ‘Nothing can harm us here.’

Her sister was wrong.

Because the second reason was that it was the day Teresa witnessed another type of combat, a different, confusing sort, which reminded her of two maras she had once seen scrapping on the Pampas. Only these were no maras: one was her father, and neither he nor the woman he was fighting with had any clothes on. Moreover, there was the faint inkling that this woman should be her beloved mama—and wasn’t.

It happened in the evening. The twins were outside; shadows from the trees lengthened and stretched in the lowering sun, and the air carried its usual aroma of vanilla and earth. Calida was on her knees, taking pictures with the camera Diego had given her that morning. She had been obsessed with photography for ages, and had waited patiently for this gift. ‘You’re old enough now,’ Diego had told her, smiling fondly as Calida basked in his love, always her papa’s angel. He never looked at Teresa that way, or gave her such special birthday presents. Teresa was too silly, too wistful; too girlish. Instead Diego spent time with Calida, teaching her the ways of the farm and entrusting her with practical tasks he knew she would carry out with her usual endurance and fortitude, while Teresa drew a picture he never commented on or wrote a poem he never read. Calida would be the one to find them later and tell her how good they were, and insist on pinning them to the wall. Teresa remembered she had her mother’s affection. That, at least, was something Calida didn’t have.

‘I’m going to wake Mama.’ Teresa stood and dusted off her shorts.

Her sister glanced up. ‘Don’t.’

‘Why not? It’s our birthday.’

‘She already saw us today.’ Indeed, Julia had graced them with her presence that morning, thirty minutes at breakfast in her night robe, pale-faced and sad-eyed.

‘She’ll want to see me again.’ Teresa said it because she knew it would hurt. She loved her sister deeply, an unquestioning, imperative love, but sometimes she hated her too. Calida was clever and useful and smart. What was she, in comparison? The youngest, made to follow directions and do as she was told. Why couldn’t she have been born first? Then her father would respect her. Then she could make her own decisions. Jealousy, a nascent seed, had grown over the years into creeping ivy.

‘Whatever.’ Calida pretended Julia’s preference didn’t wound her but her sister knew better. Teresa knew every little thing she thought or felt. ‘I don’t care.’

Teresa stalked past. It was as though the twins could argue on the barest of words, those surface weapons sufficient, like ripples on the deepest ocean.

Inside the house, it was cool and quiet. Teresa glanced down the hallway and decided she would take her mother a sprig of lavender, her favourite. She knew where the best of the purple herb grew, at the side of the stables, and went to find some. She imagined Julia’s face when she handed her the lilac bouquet, and lifted at the thought.

A strange sound came upon her slowly. At first she thought it was an animal in pain, one of the horses, maybe, and she hoped it wasn’t Paco.

But as she drew nearer, she knew it wasn’t that at all.

Teresa stopped by the stable door. The scent of lavender enveloped her, heady and sweet, and from that day forward it would eternally be associated with sex. In her adult years, in fields in France or in gardens in England, in perfumed tea-blends or in Hollywood spas, it would carry with it an echo of that exotic, bewildering revelation, all the more tender for the age at which she had discovered it.