По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

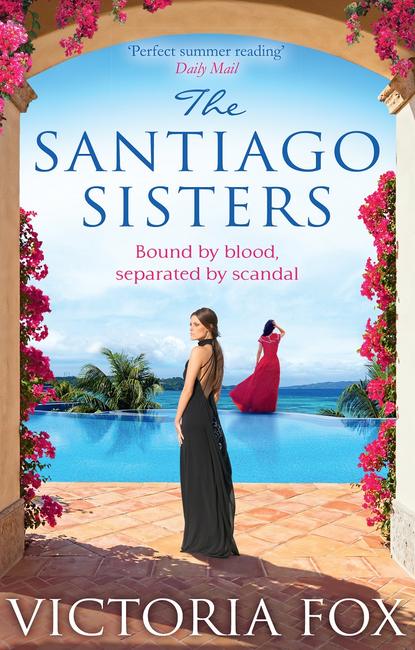

The Santiago Sisters

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The internet? Are they in a catalogue or something?’

Michelle stepped back. ‘You’re not considering it, surely,’ she said.

‘Why not?’

‘What does Brian think?’

Right then, Simone couldn’t give a hooting crap what Brian thought. He wouldn’t know what it was like to go through life with no child to call her own. He wouldn’t understand. As with all else in their marriage, Simone would make the decision herself and then she would inform him of it. His opinion mattered not a jot. ‘Michelle, I want you to look into it for me.’

Michelle was used to dealing with her clients’ whims—this one would blow over in a week. ‘OK,’ she agreed. ‘Do you want a brown one?’

‘No.’

‘A Chinese one?’

‘No.’

‘Mexican? Filipino?’

‘I’m not ordering a goddamn takeaway. I don’t know.’

‘I’ll get you some information.’

‘Good. This could be the missing piece, Michelle. It really could.’

Brian joined them. On a happy impulse, Simone leaned in to kiss his cheek. A passing paparazzo captured the moment. ‘Hello, baby,’ he said, chuffed.

Hello, baby …

Except it wouldn’t be a baby. She had her own reasons for that. It would be a child. Hello to the child who was somewhere out there, halfway across the world, waiting to be plucked from poverty to riches, from obscurity to the spotlight, from nothing to having it all. What little girl wouldn’t want that?

She smiled. It would happen—and soon.

For, when Simone Geddes put her mind to something, she did not fail.

4 (#ulink_c39f7568-4c1e-5c79-a873-d68f5cdeffee)

Argentina

In the autumn, without explanation, Señorita Gonzalez was fired. Diego appeared to make the decision overnight, and Calida didn’t dare question it—except to her sister.

‘What happened?’ she whispered.

‘I don’t know.’

‘Do you think he found out what she was really like?’

‘Maybe. Who cares? She’s gone now.’

Teresita was flicking through one of their mama’s romance novels. Calida frowned: she could read her twin just as easily as the words on the page.

‘You know something,’ she said. ‘About Gonzalez—I can tell.’

‘No, you can’t. You don’t know everything about me.’

‘I know you can’t actually like those books. Come on, A Prince’s Affair?’

Teresita bristled. ‘What’s wrong with them?’ she countered.

Calida could list the reasons from the covers alone—plastic men in open shirts with chests like dolls, smooth and hairless, and bright white teeth; how Julia swooned over their aeroplanes and chunky watches and forgot about the life that was right here in front of her. Calida thought the books looked like nonsense, but she didn’t say so, because she didn’t want to prove her twin right. They did know everything about each other—and in that case Calida didn’t need to explain what she disliked, nor Teresita what she enjoyed, so it seemed safer to walk away, and to try not to think about what Teresita was keeping from her, and why she hid it so deep, out of sight.

A month later, the girls were watching television in the barn when the phone rang.

Calida went through to the house. She lifted the receiver.

‘Hello?’

The voice on the line sounded far away. It was a woman.

‘Es la policía,’ it said. ‘My name is Officer Puerta and I need to speak with Julia, wife of Diego Santiago. Is that her?’

They manoeuvered Julia into the back of the Landrover with difficulty: she hadn’t taken the car out in years and professed to have forgotten how—and besides, how could she operate a vehicle at a time like this? She was a wife in crisis.

‘My husband,’ she kept gasping. ‘What’s happened to my husband?’

‘We have to get to him, Mama,’ said Calida. She was terrified but she couldn’t show it. She had to stay strong. She helped her sister into the passenger seat and held her hand. ‘Don’t worry,’ she told her firmly. ‘It will be all right.’ Teresita gazed back at her with a stoic expression, and it was an expression Calida couldn’t decipher. She couldn’t find a way into it. It closed on her as firmly as the car door.

Calida had driven on the shrubland before, but never on the roads and never without Diego. She crunched the gears as they rocked and bucked down the pot-holed drive, and she tried to remember what her papa had taught her about checking her mirrors and coordinating her feet. It helped to hear his voice, guiding her.

Please be OK, Papa. Please, please be OK.

Eventually, they met the highway. Vehicles rushed past at speed. When a gap opened in the traffic she set the Landrover in motion and immediately stalled, trapping them across the oncoming lane. ‘Move!’ screamed Julia from the back.

Calida floored the gas and the car lurched forward. Car horns screeched. The wheel spun in her fingers and she grappled for control, finally setting them straight.

She followed the police officer’s directions. Everything was alien, sinister. Thoughts whirled as she turned south to the waterfront. Mauve clouds streaked the sky over the town lake. Calida could see the pulsing red beams from the police vehicles and the lump in her throat swelled.

You’re going to be OK. You have to be OK.

In her heart, though, she knew.

All her life her father had been a rock, as solid and constant as the mountains of home—but lately, he hadn’t been right. Since Gonzalez had left, Diego had become unpredictable, suspicious, checking up on the girls, calling them trouble, shouting at them for the tiniest thing. What had happened? What had changed? Once, he would never have left them at night while he went to town. Now, it happened more often than not. She had listened at the door while her mama spoke to Officer Puerta, watching Julia’s knuckles grow paler by the second. There had been an accident.

They reached the blockade: a ribbon of tape, police talking grimly into their radios, and, beyond that, into the dark, dense fog of the night, a shape she couldn’t make out and didn’t want to see. Calida brought the car to a stop. They opened the doors and climbed out. Calida attempted to be close to her sister but her sister didn’t want to be close. Instead, Teresita wrapped her arms round herself and turned away. Calida swallowed a lump of sadness. I need you, she thought. Don’t you need me?

A woman saw their approach and crossed the tape.

‘Come with me,’ she told Julia. ‘The girls stay here.’