По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

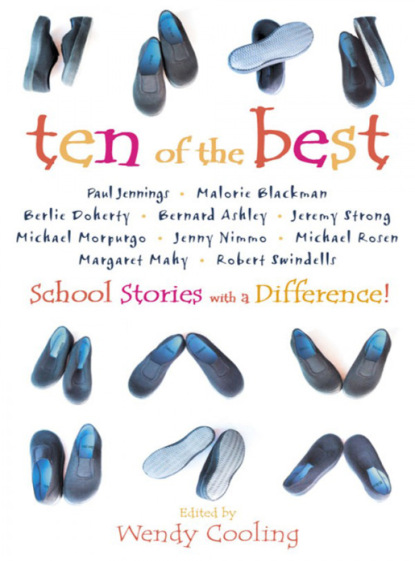

Ten of the Best: School Stories with a Difference

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The next day at school a few children called me, ‘Witchie!’ They didn’t really mean any harm. It was just ordinary teasing, and if I had been really clever I would have laughed and taken no notice. After all, anyone could see that I was just another one of the school children. Yet somehow or other the name-calling made the cackling witch spring to life in me once more. After all, if I kept on being a witch those two worlds – the everyday world and the storybook one – might melt into one another.

‘Yes,’ I told those other children, ‘I am a witch. I can do magic spells, and I also have a poisonous bite like a snake.’

But my story just did not work in the school world. Other children caught up with me on my way home from school shouting, ‘Witch! Witch! Witch!’ at me. Some of them just wanted to tease me, but there were one or two of them who were actually angry with me, and one girl swung me round yelling, ‘Witch!’ into my very face. I grabbed her arm and bit her just to prove to everyone how poisonous my bite could be. How I longed to turn those shouting children into frogs! They would have respected me then. I would have been surrounded by hopping frogs, all croaking and pleading and promising that if only I turned them back into children, they would be my friends forever. The strange thing was that I wanted other children to like me.

Anyhow, I certainly did not enjoy being a witch without magic, particularly when I was on my way home from school. Sometimes, I would run as I left the playground, making for home with other children chasing after me. Sometimes, I would turn in at strange gateways and hide on the verandas of houses that belonged to people I did not know. I would knock on doors, telling the astonished women who answered my knocking that other children were chasing me. The women would look down at me, puzzled and frowning, for they were busy, and of course they didn’t know just what was going on outside their gates. In any case, there was nothing they could do to save me. In the end I always had to go back to the street and keep running towards home. That story – the story of the witch with the poisonous bite – had certainly not worked out the way I had hoped it would. No one respected me because of it.

All the same I learned something from all this – something which altered the way I felt about the adventures other people were having at school. And to this very day, more than fifty-five years later, I can still feel that lesson working in me.

There were small shed-like shelters in our playground into which we were expected to cram ourselves if it began to rain while we were outside at playtime, and during one particular break I joined a group of children to torment another girl. I have no idea to this day why we ganged up on her, and do not even remember her name. I only know that we drove her into one of the shelter-sheds, pointed at her and cried out a nonsense rhyme that I still remember:

Stare! Stare! Like a bear,

Sitting in a monkey’s chair.

When the chair began to crack

All the fleas ran up YOUR back.

I was really enjoying being part of that chorus and part of that gang, all shouting and pointing. For once I felt I was a true part of the playground world. The girl leaped on to one of the seats in the shelter-shed and flattened herself against the wall. Suddenly, as I chanted and pointed, along with all the others, I remembered what it had been like a few weeks earlier when I was the one who was being chased, with other kids shouting, ‘Witch! Witch! Witch!’ as they ran after me. My arm flopped down at my side and I stopped chanting. If I had been a true hero I would have tried to rescue that girl who was hemmed in in the shelter-shed, but I was just too scared to try. I simply walked away.

You might think that these things – the things that happened to me and the things I saw happening to other people – might have taught me to be more sensible. No way! Though I no longer wanted to be a witch with a poisonous bite, I still wanted the everyday world to become marvellous around me. I still wanted to be the hero of some story. Day followed day in an ordinary real-world way, and then, suddenly, I had (once again) a chance to transform myself in storybook fashion. But (once again) it did not work out in the way I had hoped it would.

This time it began, not with a fancy-dress ball, but with a film that came to our local cinema. It was The Jungle Book, the story of an Indian boy, Mowgli, who, lost in the jungle when he was a baby, was adopted by wolves. Mowgli grew up among animals and learned to speak their languages, so that he could talk not only to wolves but to tigers, monkeys and snakes, as well. I loved that film. I was changed by it. Indeed, I loved it so much that I tried to make it come true for me in the everyday school-playground world.

At that time there were English children at my school – children who had been sent to live with New Zealand grandparents, so that they would escape the bombing of London. I stole part of their true story, stole part of Rudyard Kipling’s invented story and twisted them into a story of my own. ‘I flew out from London,’ I told other children in the school playground, ‘but the plane crashed in the jungle. I was found by wolves and I lived with them there in the jungle, learning to speak the language of the animals.’ This wasn’t just an invented story (I declared). It was true.

Things began slowly. I tried out this story on one or two children who told other children and my story spread around the school. Soon little groups began to challenge me once more. I did my best to prove that what I claimed was true. I invented a sort of mumbling, nonsense language which I tried out on passing dogs. When the dogs looked at me in astonishment I declared that they could understand what I was saying, but this only made the other children shout with laughter. I grew more and more determined to show them that I really belonged to the magical world of animals. What do animals do? They eat. What do they eat? I began eating grass and leaves and drinking from roadside puddles, just as some animals did, trying to prove I was truly linked to them. It was the only proof I could think of at the time.

Even when I began eating grass the other children at school were all far too sensible to believe my story. But boys and girls began to come up to me in the playground bringing handfuls of leaves and berries. ‘Eat this!’ they would demand, thrusting something – a dock leaf or a dandelion – towards me and I would eat whatever they waved in my face. I had to. I remember how some leaves burned my tongue and how horrible some of the berries tasted. However, I did not hesitate for a moment. I found out, years later, that the teachers at school knew what was going on out in the playground, but none of them interfered, though for all they knew some of the leaves and berries I was eating could have been poisonous. Once again that school playground seemed to stretch itself out all the way between school and my home. ‘Eat this! Eat this!’ other children cried as we walked home, thrusting out their grass and leaves and berries, and I would chew and then swallow whatever they offered me.

Chasing a witch with a poisonous bite can become a little boring after a while and so can the sight of someone eating leaves and drinking out of puddles. But just as other children were growing tired of seeing me eat leaves I accidentally did something that excited them all over again. I ate a leaf without noticing something that other children were already well aware of There was a caterpillar clinging to that particular leaf. If I had seen that caterpillar, I might have rescued it. Who knows? I might even have told the other children that I could talk caterpillar language. As it was, I just crammed the leaf into my mouth and ate it, caterpillar and all. Within a second other children were leaping around me screaming, ‘Ugh! Ugh! She ate a caterpillar!’ Well, I don’t really blame them.

There was no way I could enjoy what was happening to me. Indeed I hated it. It was so different from what I had imagined it would be like when I began to invent my story. Certainly, I had not turned into the mysterious and wonderful creature speaking animal language I had imagined I might be. Instead, I had become a school fool, eating leaves and caterpillars and drinking dirty water – and it was all my own fault.

Troubled times seem to go on and on. But nothing, not even a bad time, lasts forever. After a while, in spite of the caterpillar excitement, the other children lost interest in seeing me eat leaves. As for me, I fell silent. For many years I said nothing more about my magical powers. Instead, I began writing stories in little notebooks. I would go home and sit in my room scribbling tales about beautiful wild horses, and children who lived adventurous lives with pirates and gangs of outlaws. I had successfully woven my way into story-life after all, but I had to do that weaving shut away in my own room, just as I do today.

Trying to turn myself into a witch with a poisonous bite, or a child who could talk the language of animals, did not take up much of my school time. I suppose it was really only a matter of a few weeks here and there. However, whenever anyone asks me whether I enjoyed school or not, the first thing that I remember is trying out those impossible stories on other children who were all too sensible to believe me. And I also remember being part of the playground chorus tormenting that girl in the shelter-shed.

I learned a lot at school – I learned to read and write, and I learned the multiplication tables – things which I use every day. But I also learned how stories can work in the world. The odd thing is that nowadays, when I watch the news on television, it seems to me that heads of many countries are trying hard to make everyone else believe that they are the true heroes of the world’s stories, and that other countries around them are ruled by villains. I haven’t yet seen any prime minister or president eating grass…but who knows? They tell powerful stories and then have to prove them, so one of these days they might do just that.

Robert Swindells Porkies (#ulink_cf93b47a-4b04-5ccd-977f-3bff26c90a86)

Mount Everest

ROBERT SWINDELLS was in the RAF for three years, then had a variety of jobs including shop assistant, clerk, printer and engineer. He trained as a teacher, the taught for eight years before becoming a full-time writer. He won the children’s Rights Workshop Other Award for Brother in the Land which also won again for Room 13 and, in the shorter novel category, for Nightmare Stairs. He won the Carnegie Medal for Stone Cold and the Angus Book Award for Unbeliever.

Robert Swindells Porkies (#ulink_47b5c5ad-8f15-5127-b5dd-d578342b360a)

Piggo Wilson was an eleven-plus failure. We all were at Lapage Street Secondary Modern School, or Ecole Rue laPage as we jokily called it. Eleven-plus was this exam kids used to take in junior school. It was crucial, because it more or less decided your whole future. Pass eleven-plus and you qualified for a grammar school education, which meant you went to a posh school where the kids wore uniforms and got homework and learned French and Latin and went on trips to Paris. At Grammar School you left when you were sixteen to start a career, or you could stay on till you were eighteen and go to university. Fail eleven-plus and you were shoved into a Secondary Modern School where you wore whatever happened to be lying around at home and learned reading, writing and woodwork. You couldn’t get any qualifications and you left on your fifteenth birthday and got a job in a shop or factory. Not a career: a job.

One of the rottenest things about being an eleven-plus failure was that you knew you’d let your mum and dad down. Everybody’s parents hoped their kid would pass and go to the posh school. Some offered bribes: pass your eleven-plus son, and we’ll buy you a brand new bike. Others threatened: fail your eleven-plus son, and we’ll drag yer down the canal and drown yer. But grammar school places were limited and there were always more fails than passes.

It wasn’t nice, knowing you were a failure. Took some getting used to, especially if your best friend at junior school had passed. You’d go and call for him Saturday morning same as before, only now his mum would answer the door and say, ‘Ho, hai’m hafraid William hasn’t taime to come out and play: he’s got his Latin homework to do.’ William. It was Billy before the exam. You’d call round a few more times, then it’d dawn on you that you wouldn’t be playing with William any more. Grammar School boy, see: can’t be seen mixing with the peasants.

Most kids took it badly one way or another, but it seemed to bear down particularly heavily on Piggo. The rest of us compensated by jeering at the posh kids, whanging stones at them or beating them up, but that didn’t satisfy Piggo. What he started doing was telling these really humungous lies about himself. He’d stroll into the playground Monday mornings and say something like, ‘Went riding Saturday afternoon with my grandad, bagged a wildcat.’ He’d say it with a straight face as well, even though everybody knew he’d never been anywhere near a horse in his life and wildcats lived in Scotland. In fact if you pointed this out he’d say, ‘Yes, that’s where we rode to, Scotland.’ Or we’d be listening to Dick Barton on the wireless and he’d say, ‘My dad’s a special agent too, y’know: works with Barton now and then.’ If you pointed out that Dick Barton was a fictional character he’d wink and tell you that was Barton’s cover story. He couldn’t help it, old Piggo: he needed to feel he was special to make up for everybody else seeing him as a failure.

Anyway that’s how things were, and by and by it got to be 1953. There was something special about 1953, even at Lapage Street Secondary Modern School, because of two momentous events which took place that year. One was the coronation of the young Queen Elizabeth at Westminster Abbey. ‘My cousin’ll be there,’ claimed Piggo, ‘she’s a lady-in-waiting.’ ‘She’s a lady in Woolworth’s,’ said somebody: a correction Piggo chose to ignore.

The other momentous event was the conquest of Mount Everest. For decades, expeditions from all over the world had battled to reach the summit of the world’s highest peak, and many climbers had hurtled to their deaths down its icy face. Finally, in 1953, a British expedition succeeded in putting two men on the summit. They planted the Union Jack and filmed it snapping in a freezing wind. The pictures went round the world and the people of Britain surfed on a great wave of national pride: a wave made all the more powerful because it was coronation year.

As coronation day approached, and while the Everest expedition was still only in the foothills of the Himalayas, our teachers decided that Lapage Street Secondary Modern School would stage a patriotic pageant to mark the Queen’s accession to the throne, and to celebrate the dawn of a New Elizabethan Age with poetry, song and spectacle. A programme was worked out. Rehearsals began. An invitation was posted to the Lord Mayor who promised to put in an appearance on the day, should his busy schedule permit.

We failures were excited, not by all these preparations but by the prospect of the day’s holiday we were to get on coronation day itself, and the souvenir mug crammed with toffees every child in the land was to receive. I say all, but it would be more accurate to say all but one of us was excited. While the rest of us laboured to memorise a very long poem about Queen Elizabeth the First and hoarded our pennies to buy tiny replicas of the coronation coach, Piggo Wilson sank into a long sulk because he couldn’t get anybody to believe his latest story, which was that Mount Everest had actually been conquered years ago in a solo effort by his uncle.

He’d tried it on Ma Lulu first. Her real name was Miss Lewis. She was the only woman teacher in our all-boys’ school and she took us for Divinity, which is called RE now. On the day the news broke that Sir John Hunt’s expedition had planted the Union Jack on the roof of the world, she was talking to us about the courage and endurance of Sherpa Tensing and Edmund Hillary, the two men who’d actually reached the summit, when Piggo’s hand went up.

‘Yes, Wilson?’ We didn’t use first names at Lapage.

‘Please Miss, they weren’t the first.’

Ma Lulu frowned. ‘Who weren’t? What’re you blathering about, boy?’

‘Hillary and Sherpa whatsit, Miss. They weren’t the first, my uncle was.’

‘Your uncle?’ She glared at Piggo. We were all sniggering. We daren’t laugh out loud because Ma Lulu had two rulers bound together with wire which she liked to whack knuckles with. Rattling, she called it.

‘Are you asking us to believe that an uncle of yours climbed Mount Everest, Wilson?’

‘Yes, Miss.’

‘Rubbish! Who told you this, Wilson? Or are you making it up as you go along, I expect that’s it, isn’t it?’

‘No Miss, my dad told me. My uncle was his brother, Miss.’ Sniggers round the room.

‘What’s his name, this uncle?’

‘Wilson Miss, same as me, only he’s dead now.’

‘His first name, laddie: what was his first name?’

‘Maurice Miss: Maurice Wilson.’

‘Well I’ve never heard of a mountaineer called Maurice Wilson.’ She appealed to the class. ‘Has anybody else?’

We mumbled, shook our heads. ‘No,’ snapped Ma Lulu, ‘of course you haven’t, because there’s no such person.’ She glared at Piggo. ‘If this uncle of yours had conquered Mount Everest, Wilson, everybody would know his name: it would have become a household word as Hillary has, and Tensing.’

‘But Miss, he didn’t get back so it couldn’t be proved. Some people say he never reached the top, Miss.’