По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

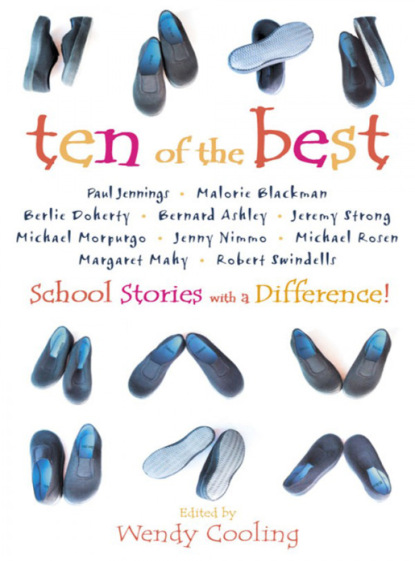

Ten of the Best: School Stories with a Difference

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Wilson,’ said Ma Lulu patiently, ‘two weeks ago I set this class an essay on the parable of the Good Samaritan. You wrote that you’d been to Jericho for your holidays and stayed at the actual inn.’ She regarded him narrowly. ‘That wasn’t quite true, was it?’

‘No Miss,’ mumbled Piggo.

‘Where did you actually spend those holidays, laddie?’

‘Skegness Miss.’

‘Skegness.’ She arched her brow. ‘Does Jesus mention Skegness at all in that parable, Wilson?’

‘No Miss.’

‘No Miss He does not, and why? Because Jesus never visited Skegness, and your uncle never visited Everest.’ She sighed. ‘I don’t know what’s the matter with you, Wilson: not only do you insult me by interrupting my lesson with your nonsense, you insult those brave men who risked their lives to plant the Union Jack on the roof of the world. Open your jotter.’

Piggo opened his jotter. ‘Write this: I have never been to Jericho, and my claim that my uncle climbed Mount Everest is another wicked lie, of which I am deeply ashamed.’ Piggo wrote laboriously, the tip of his tongue poking out. When he’d finished Ma Lulu said, ‘You will write that out a hundred times in your very best handwriting and bring it to me in the morning.’

We all had a good laugh at Piggo’s expense, but an amazing thing happened next morning. Instead of presenting his hundred lines, Piggo brought his dad. He didn’t look like a special agent, but nobody’d expected him to. We watched the two of them across the yard, but we had to wait till morning break to find out what it was all about. Turned out Piggo’s late uncle had made a solo attempt on Everest back in the thirties and had been found a year later 7,000 feet below the summit, frozen to death. The climbers who found him claimed they also found the Union Jack he’d taken with him, which seemed to prove he hadn’t reached the summit, but the story in the Wilson family was that Maurice had taken two flags, left one on the peak and died on the way down. The climbers had found his spare. The fact that nobody outside the family believed this didn’t worry them at all.

Ma Lulu probably didn’t believe that part either, but she was as gobsmacked as the rest of us to learn that Piggo’s tale was even partly true. She apologised handsomely, cancelled his punishment and used our next Divinity lesson to tell us the story of Maurice Wilson’s brave if foolhardy attempt to conquer the world’s highest peak all by himself We were a bit wary of Piggo after that, but taunted him slyly about his family’s version of the outcome. He stuck to his guns, insisting that his uncle had beaten Tensing and Hillary by more than twenty years.

Our pageant came and went. The Lord Mayor didn’t. He had another engagement but his deputy attended, wearing his modest chain of office. Some parents came too. Piggo’s mum was one of them, which is how we found out she wasn’t a Siamese twin as her son had insisted. On coronation day school was closed. There were very few TVs then, so most people listened to bits of the ceremony on the wireless. Most adults I mean. We kids had better things to do, like setting the golf-course on fire as an easy way of uncovering the lost balls we sold to players at a shilling each.

For us, the best bit of that momentous year came a few weeks later. The Headmaster announced in assembly that a local cinema was to show films in colour of the coronation ceremony, including the Queen’s procession through London in her golden coach, and of the conquest of Everest, compiled from footage shot by expedition members, including the final assault on the peak and views from the summit. Pupils from schools across the city would go with their teachers to watch history being made in this stupendous double bill. There’d be no charge, and our school was included.

We could hardly wait, and Piggo was even more impatient than the rest of us. ‘Now you’ll see,’ he crowed, ‘it’ll show the peak just before those losers Tensing and Hillary stepped on to it and my uncle’s flag’ll be there, flapping in the wind.’ We smiled pityingly and shook our heads, but he seemed so confident that as the day approached, our smug certainty wavered a bit.

It was at the Ritz, right in the middle of the city. A fleet of coaches had been laid on to carry the hundreds of kids from schools all over the district. Ours didn’t arrive first. We piled off and joined a queue that curved right round the building. The class in front of us was from one of the grammar schools so we spat wads of bubblegum, aiming at their hair and the backs of their smart blazers. Red-faced teachers darted about, yanking kids out of the queue and shaking them, hissing through bared teeth, ‘D’you think Her Majesty spat bubblegum all over Westminster Abbey: did Sherpa Tensing spag a wad from the summit to see how far it would go, eh?’ It made the time pass till they started letting us in.

They ran the coronation first. It was quite a spectacle, the scarlet and gold of the uniforms and regalia sumptuous in the grey streets, but it didn’t half go on. We got bored and began taunting Piggo. ‘Which one’s your cousin then, Wilson: you know, the lady-in-waiting?’

‘Ssssh!’ went some teacher, but it was dark: he couldn’t see who was talking. ‘Come on Wilson,’ we urged, ‘point her out.’ Piggo made a show of craning forward to peer at the faces in the procession. There were hundreds. After a bit he pointed to an open carriage that was being pulled by four horses. ‘There!’ he cried, ‘that’s her, in that cart.’ Just then the camera zoomed in, revealing that the woman was black. We shouted with laughter, and Piggo muttered something about having relatives in the colonies. As the camera lingered on her face, the commentator told us the woman was the Queen of Tonga.

The film dragged on. A great aunt of mine, who had a bit of money and owned the only TV in our family, had had people round on coronation day. Those early TVs had seven-inch screens, the picture was black and white, or rather black and a weird bluish colour, the image so fuzzy you had to have the curtains drawn if you wanted to see anything. Coverage had lasted all day, and my great aunt’s guests had sat with their eyes glued to it from start to finish. Get a life I suppose we’d say nowadays, but it was the novelty: none of those people had seen a TV before. Anyway, I was thankful not to have been there.

The Everest film was a great deal more interesting to kids like us. Much of it had been shot with hand-held cameras on treacherous slopes in howling gales so you got quite a lot of camera-shake, but the photographers had captured some breathtaking scenery, and it was interesting to see mountaineers strung out across the snowfield roped together, stumping doggedly upward with ice-clotted beards. Another interesting thing was the mounds of paraphernalia lying around their camps: oxygen cylinders, nylon tents, electrically-heated snowsuits, radio transmitters and filming equipment, not to mention what looked like tons of grub and a posse of Sherpas to hump everything. Brought home to us how pathetically underequipped Piggo’s uncle had been with his three loaves and two tins of oatmeal, his silken flag. Or had it been two silken flags? Underequipped anyway.

We sat there gawping, absorbed but waiting for the climax: that first glimpse of the summit which would silence poor Piggo once and for all, and he was impatient too, confident we’d see his uncle’s flag and be forced to eat our words. It was a longish film, but presently the highest camp was left behind and we were seeing shaky footage of Tensing: ‘Tiger,’ the press would soon christen him, inching upward against the brilliant snow, and of Hillary, filmed by the Sherpa. We were getting occasional glimpses of the peak too, over somebody’s labouring shoulder, but it was too distant for detail. There was what looked like a wisp of white smoke against the blue, as though Everest were a volcano, but it was the wind blowing snow off the summit.

Presently a note of excitement entered the narrator’s voice and we sat forward, straining our eyes. The lead climber had only a few feet to go. The camera, aimed at his back, yawed wildly, shooting a blur of rock, sky, snow. Any second now it’d steady, focusing on the very, very top of the world. We held our breath, avid to witness this moment of history whether it included a silken flag or not.

The moment came and there was no flag. No flag. There was the tip of Everest, sharp and clear against a deep blue sky and it was pristine. Unflagged and, for a moment longer, unconquered. A murmur began in thirty throats and swelled, the sound of derision. ‘Wilson you moron,’ railed someone, ‘where is it, eh: where is your uncle’s silken flipping flag?’

Piggo sat gutted. Crushed dumb. We watched as he shrank, shoulders hunched, seeming almost to dissolve into the scarlet plush of the seat. Fiercely we exulted at his discomfiture, his humiliation, knowing there’d be no more bragging, no more porkies from this particular piggo. The film ended and we filed out, nudging him, tripping him up, sniggering in his ear.

We were feeling so chipper that when we got outside we looked around for some posh kids to kick, but they’d gone. This small disappointment couldn’t dampen our spirits however. We knew that what had happened inside that cinema: the final, irrevocable sinking of Piggo Wilson was what we’d remember of 1953. We piled on to our coach, which pulled out and nosed through the teatime traffic, bound for Ecole Rue laPage. When we came to a busy roundabout the driver had to give way. In the middle of the roundabout was a huge equestrian statue; the horse rearing up, the man wearing a crown and brandishing a sword. Piggo, who’d been sitting very small and very quiet, pointed to the statue of Alfred the Great and said, ‘See the feller on the horse there: he was my grandad’s right-hand man in the Great War.’

Berlie Doherty The Puppet Show (#ulink_6d256e2d-7eb7-5854-81b9-866d1afd0d57)

‘My theatre’s broken.’

BERLIE DOHERTY started writing seriously at university, where she was studying to be a teacher. She has twice won the prestigious Carnegie Medal, once for Granny Was a Buffer Girl – in which there was a whole chapter based on her parents – and once for Dear Nobody, the playscript of which won the Writers’ Guild Award. Daughter of the Sea also won the Writers’ Guild Award. Her other books include The Snake-stone, Street Child, The Sailing-ship Tree, Tough Luck, Spellhorn and Holly Starcross.

Berlie Doherty The Puppet Show (#ulink_01c77beb-32cf-5dc1-b2ee-7c6513b91558)

It began with Mickey and Minnie Mouse. My older brother, Denis, gave them to me for my ninth birthday. I had just left the little school in Meols at the time. I loved that school. In winter we had a real coal fire in the classroom, and when it grew dark the flames would flicker shapes and shadows on the walls until the light was put on. You could hear the sea from the yard. In the autumn we gathered chestnuts and leaves from the monkey woods round the school and brought them in to decorate the walls and windows. Some children hardened the chestnuts in vinegar and made holes in them, then threaded them with bits of string for conker fights in the playground. I liked to line mine up on my desk, admiring the way they gleamed like brown eyes. At the end of the day we used to run home along the prom, with the gritty sand whistling round our bare legs, and if there was time we’d play out till dark.

But the autumn term in the year of my ninth birthday had hardly started when the parish priest told my parents that I should be going to a Catholic school, and persuaded them to take me away from there. So I had a long journey by bus to a large flat school in the middle of a modern housing estate. There was a plaster statue of a saint in every classroom. Our room had the Virgin Mary in a blue dress, and she seemed to be watching us all the time with her sorrowing eyes. Occasionally the sickly smell of chocolate drifted in through the windows from the nearby Cadbury’s factory, mingling with the smell of boiling cabbage or fish from the kitchens.

By the time I started there, nearly halfway through the autumn term, friendships had already been made. I was much too shy to talk to anyone, and nobody talked to me. I used to stand in the windy playground with my back against the railings and watch all the children running and shrieking and wonder how there could be so many children in one place, and how they could all know each other. I wished I could squeeze through the railings and run back home. When Mr Grady blew the whistle at the end of playtime the children all froze like the statues in the classrooms, and then at his second whistle they walked absolutely silently into class rows. There wasn’t a child in the school who wasn’t afraid of Mr Grady. His face was cold and hard and white, and I don’t think I ever saw him smile.

One day he caught me reading in a lesson. I was supposed to be doing Arithmetic. I felt his hand coming over my shoulder and too late, he snatched the book away from my grasp and held it up. I was ice-cold with fear. The whole class watched him as he walked with the book to his desk. He had been known to beat children with his cane until they bled. He sat on the edge of his desk and drew a pile of exercise books towards him. Then he rooted through them and drew one out. It was mine.

‘One day,’ he said to the class, ‘this girl will be a writer.’

But I did not feel proud or happy that he had said that. I felt afraid, and ashamed. I hung my head and didn’t look at anyone.

Our class teacher was Miss O’Brien, who had auburn hair like a fox’s back. Her lips were bright red and shiny, as if she was always licking them wet, though I never saw her doing it. I longed to be noticed by her, but she always seemed to be in a dream, gazing out of the window as she taught us, somewhere far away. And around me, the children in the class giggled quietly and passed notes to each other, and shared secrets. They all seemed to be going to each other’s houses for tea or to birthday parties. I was outside it all, just watching.

When my own birthday came around, in November, there was no point having a party. There was no one to invite. So it was a special treat when my brother arrived home unexpectedly, especially as he brought me two presents. ‘I couldn’t decide which one to get you,’ he said. ‘So I got them both.’

They were glove puppets, one of Mickey in a blue smock, one of Minnie in a pink smock with a yellow bow painted on her shiny black rubber head. They both had round beaming cheeks and huge smiling eyes. The heads were hollow, so I could put my hand inside them and bunch up my fist in the cheeks. The smocks covered my hands. I could make the heads bob about and look round and talk to each other. Everybody laughed when I made funny voices and made the puppets talk. I found I could say anything I liked with these puppets on my hands, and nobody minded. I could tell Jean, my sister, that her hairstyle was horrible, or her new dress looked like a sack of potatoes, and as long as I said it in Mickey’s voice she thought it was really funny.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: