По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

The Witness for the Prosecution: And Other Stories

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Witness for the Prosecution: And Other Stories

Agatha Christie

Agatha Christie’s classic short story collection, published to tie-in with a new BBC TV adaptation of the book’s most enduring and shocking thriller, The Witness for the Prosecution.1920s London. A murder, brutal and bloodthirsty, has stained the plush carpets of a handsome London townhouse. The victim is the glamorous and enormously rich Emily French. All the evidence points to Leonard Vole, a young chancer to whom the heiress left her vast fortune and who ruthlessly took her life. At least, this is the story that Emily’s dedicated housekeeper Janet Mackenzie stands by in court. Leonard however, is adamant that his partner, the enigmatic chorus girl Romaine, can prove his innocence.

Copyright (#ulink_968931c5-87a2-54c0-962d-8cd473cbc2d2)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

‘The Witness for the Prosecution’, ‘The Fourth Man’, ‘The Mystery of the Blue Jar’, ‘The Red Signal’, ‘S.O.S.’ and ‘Wireless’ previously published in the UK in The Hound of Death (1933).

‘Accident’, ‘Mr Eastwood’s Aventure’, ‘Philomel Cottage’ and ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’ previously published in the UK in The Listerdale Mystery (1934).

‘The Second Gong’ previously published in the UK in Problem at Pollensa Bay (1991).

‘Poirot and the Regatta Mystery’ previously published in the UK in Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories (2008).

Witness for the Prosecution®, Agatha Christie®, Poirot® and the Agatha Christie Signature are registered trade marks of Agatha Christie Limited in the UK and elsewhere.

This collection copyright © Agatha Christie Limited 2016

All rights reserved.

www.agathachristie.com (http://www.agathachristie.com)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

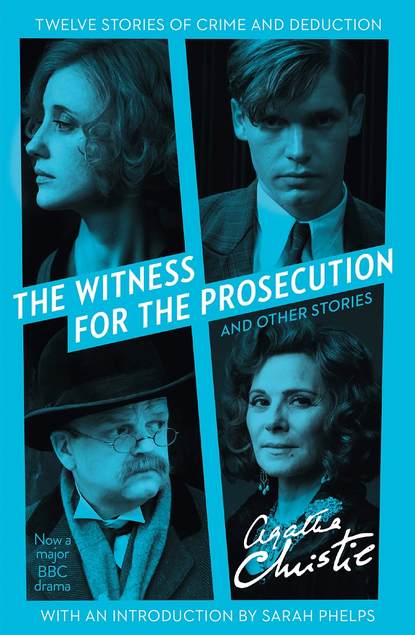

Cover photographs by Todd Anthony (Kim Cattrall) and Robert Viglasky © Agatha Christie Productions and Mammoth Screen 2016

From the major BBC series The Witness for the Prosecution starring Kim Cattrall, Billy Howle, Toby Jones and Andrea Riseborough

Agatha Christie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008201258

Ebook Edition © December 2016 ISBN: 9780008201265

Version: 2017-09-13

Contents

Cover (#u8169a72a-0782-52b5-a3ff-4ccce20f3558)

Title Page (#uf9b71289-1ed4-50fd-8b3e-29239370d10f)

Copyright (#u030a1193-8812-5a9f-be0b-8218bcc3b179)

Introduction (#uc1091b7c-d541-5c59-b7ca-b6eb612c0df1)

1. The Witness for the Prosecution (#u80cb489d-1f4f-515e-b4dd-0ee851d9e4df)

2. Accident (#ua07919d2-493e-535d-97a7-263032e897cd)

3. The Fourth Man (#u4abb2d1d-02c9-5450-a8b9-60b49631a835)

4. The Mystery of the Blue Jar (#litres_trial_promo)

5. Mr Eastwood’s Adventure (#litres_trial_promo)

6. Philomel Cottage (#litres_trial_promo)

7. The Red Signal (#litres_trial_promo)

8. The Second Gong (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Sing a Song of Sixpence (#litres_trial_promo)

10. S.O.S. (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Wireless (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Poirot and the Regatta Mystery (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnote (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Agatha Christie (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_b152fe83-b755-52fd-aa65-f5e274f22b7c)

I should come clean from the start. Until a few years ago, I had never read anything by Agatha Christie, nor had I ever watched one of the many adaptations of her novels. I’d seen bits of them, yes, but watched them from beginning to end, no. I’d walked past the St Martin’s Theatre, where The Mousetrap has been running for over 60 years, hundreds of times, stepping into the street to avoid the queues on the pavement. The name Agatha Christie was wholly familiar to me and so I thought I knew what she was all about: vicarages and village greens, the Orient Express and the Nile, country houses, clipped accents and a corpse on the floor. ‘Murder!’ somebody shrieks, but the murder really serves as catalyst for the ludic delights of the mystery and an abundance of cryptic clues that only the outsiders – such as the sharp-eyed and sharp-tongued spinster Miss Jane Marple or the extravagantly moustachioed Belgian detective Hercule Poirot – can unravel. It’s entertainment. Cosy. The epitome of a particular nostalgia-laden Englishness. The mystery is satisfactorily resolved, the villain is identified and the status quo restored. Everything is alright in The End. That is what I thought.

Then I was asked to read And Then There Were None to adapt it for the BBC, and the savagery of the novel knocked me sideways. Ten strangers are invited to a remote island by a mysterious host. Archetypal characters: the Doctor, the General, the Detective, the Judge, the Schoolmistress, the Spinster, the Butler, like pieces set out for a board game. A recorded voice accuses them all of murder and names their victims. One by one, the characters die, the manner of their deaths in keeping with a chilling nursery rhyme. They search for the murderer but there is no one else on the island. The killer is one of them. But which one?

And Then There Were None is many things: the ultimate locked-room mystery; a nerve-shredding psychological thriller; a forensic disquisition on the nature of guilt; a portrait of a psychopath … and despite the flashes of mordant wit, it is terrifying. Ten isolated and paranoid characters, facing a brutal and remorseless reckoning from which there is no possible mitigation, no chance to plead and nowhere to hide. No sleuth will arrive to interpret the clues, apprehend the villain and restore order, and the only thing you can do is try desperately to survive. Cosy is the very last thing it is. It also struck me that this is a novel of its time. Written and published in 1939, as the world was about to be precipitated into another cataclysmic war, the story felt on the very edge of the chaos and slaughter of the Second World War and, simultaneously, shockingly contemporary. It also felt profoundly subversive.

Following And Then There Were None, I was asked to read The Witness for the Prosecution for a two-hour BBC adaptation. It is a story of sex, money, deceit, performance and murder with the most glorious, sleight-of-hand twist. It has all the elements of classic Noir – murky motives, an enigmatic femme fatale and a seemingly decent man drawn deep into the web. It is set (as are many of the stories in this collection) in the deeply divided 1920s, an era of giddy hedonistic excess, champagne, shingled hair, the sizzle and thrill of jazz for some but grinding penury and want for most. It’s a world of grimy boarding houses, dank streets thick with chill fog, flickering gaslights and the cold clear light of the courtroom. The shadow of the First World War, with its seismic upheavals, ruptured certainties, scars and horrors, looms darkly. In the TV adaptation Leonard Vole, the penniless young man accused of seducing and manipulating the wealthy, indulgent Emily French into making her will in his favour, and then murdering her, tells his pedantic solicitor John Mayhew

that he hadn’t been able to ‘settle to anything, not since service’. This detail thrums with battle trauma. Romaine, a Viennese actress and the only person who can speak in Vole’s defence, is considered to have got her ‘hooks’ into Vole to get herself out of the scorched ruins of Europe. She is a ‘dangerous woman’, thinks Mayhew, ‘very dangerous.’ He has no idea.

The story is rife with the bat-squeaks of transgression. The relationship between Emily French and Leonard Vole that Vole describes as motherly could equally be perceived as sexual. Janet the maid is described as so consumed with loathing and jealousy that you wonder at the dynamic of the household that Vole becomes a part of. Even Mayhew, with his dry little cough and his pince-nez and his adherence to ‘normal procedure’, isn’t immune to transgression. He is fascinated by Romaine to the point of obsession. His stuffy legal language is abandoned for eroticism during her very public humiliation; her ‘exquisite body’, how she flames and flaunts herself ‘like a tropical flower’. You can’t help but feel how much he’s enjoying watching Romaine break while the rest of the court judges her. The scarlet woman – not so dangerous now. The twist, when it comes, explodes like a bomb. The law is flawed. Justice is entirely fallible, driven by emotion, and emotions are easily manipulated. It’s not the truth that matters, Christie seems to suggest, but performance. Performance is everything.

Agatha Christie

Agatha Christie’s classic short story collection, published to tie-in with a new BBC TV adaptation of the book’s most enduring and shocking thriller, The Witness for the Prosecution.1920s London. A murder, brutal and bloodthirsty, has stained the plush carpets of a handsome London townhouse. The victim is the glamorous and enormously rich Emily French. All the evidence points to Leonard Vole, a young chancer to whom the heiress left her vast fortune and who ruthlessly took her life. At least, this is the story that Emily’s dedicated housekeeper Janet Mackenzie stands by in court. Leonard however, is adamant that his partner, the enigmatic chorus girl Romaine, can prove his innocence.

Copyright (#ulink_968931c5-87a2-54c0-962d-8cd473cbc2d2)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

‘The Witness for the Prosecution’, ‘The Fourth Man’, ‘The Mystery of the Blue Jar’, ‘The Red Signal’, ‘S.O.S.’ and ‘Wireless’ previously published in the UK in The Hound of Death (1933).

‘Accident’, ‘Mr Eastwood’s Aventure’, ‘Philomel Cottage’ and ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’ previously published in the UK in The Listerdale Mystery (1934).

‘The Second Gong’ previously published in the UK in Problem at Pollensa Bay (1991).

‘Poirot and the Regatta Mystery’ previously published in the UK in Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories (2008).

Witness for the Prosecution®, Agatha Christie®, Poirot® and the Agatha Christie Signature are registered trade marks of Agatha Christie Limited in the UK and elsewhere.

This collection copyright © Agatha Christie Limited 2016

All rights reserved.

www.agathachristie.com (http://www.agathachristie.com)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs by Todd Anthony (Kim Cattrall) and Robert Viglasky © Agatha Christie Productions and Mammoth Screen 2016

From the major BBC series The Witness for the Prosecution starring Kim Cattrall, Billy Howle, Toby Jones and Andrea Riseborough

Agatha Christie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008201258

Ebook Edition © December 2016 ISBN: 9780008201265

Version: 2017-09-13

Contents

Cover (#u8169a72a-0782-52b5-a3ff-4ccce20f3558)

Title Page (#uf9b71289-1ed4-50fd-8b3e-29239370d10f)

Copyright (#u030a1193-8812-5a9f-be0b-8218bcc3b179)

Introduction (#uc1091b7c-d541-5c59-b7ca-b6eb612c0df1)

1. The Witness for the Prosecution (#u80cb489d-1f4f-515e-b4dd-0ee851d9e4df)

2. Accident (#ua07919d2-493e-535d-97a7-263032e897cd)

3. The Fourth Man (#u4abb2d1d-02c9-5450-a8b9-60b49631a835)

4. The Mystery of the Blue Jar (#litres_trial_promo)

5. Mr Eastwood’s Adventure (#litres_trial_promo)

6. Philomel Cottage (#litres_trial_promo)

7. The Red Signal (#litres_trial_promo)

8. The Second Gong (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Sing a Song of Sixpence (#litres_trial_promo)

10. S.O.S. (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Wireless (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Poirot and the Regatta Mystery (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnote (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Agatha Christie (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_b152fe83-b755-52fd-aa65-f5e274f22b7c)

I should come clean from the start. Until a few years ago, I had never read anything by Agatha Christie, nor had I ever watched one of the many adaptations of her novels. I’d seen bits of them, yes, but watched them from beginning to end, no. I’d walked past the St Martin’s Theatre, where The Mousetrap has been running for over 60 years, hundreds of times, stepping into the street to avoid the queues on the pavement. The name Agatha Christie was wholly familiar to me and so I thought I knew what she was all about: vicarages and village greens, the Orient Express and the Nile, country houses, clipped accents and a corpse on the floor. ‘Murder!’ somebody shrieks, but the murder really serves as catalyst for the ludic delights of the mystery and an abundance of cryptic clues that only the outsiders – such as the sharp-eyed and sharp-tongued spinster Miss Jane Marple or the extravagantly moustachioed Belgian detective Hercule Poirot – can unravel. It’s entertainment. Cosy. The epitome of a particular nostalgia-laden Englishness. The mystery is satisfactorily resolved, the villain is identified and the status quo restored. Everything is alright in The End. That is what I thought.

Then I was asked to read And Then There Were None to adapt it for the BBC, and the savagery of the novel knocked me sideways. Ten strangers are invited to a remote island by a mysterious host. Archetypal characters: the Doctor, the General, the Detective, the Judge, the Schoolmistress, the Spinster, the Butler, like pieces set out for a board game. A recorded voice accuses them all of murder and names their victims. One by one, the characters die, the manner of their deaths in keeping with a chilling nursery rhyme. They search for the murderer but there is no one else on the island. The killer is one of them. But which one?

And Then There Were None is many things: the ultimate locked-room mystery; a nerve-shredding psychological thriller; a forensic disquisition on the nature of guilt; a portrait of a psychopath … and despite the flashes of mordant wit, it is terrifying. Ten isolated and paranoid characters, facing a brutal and remorseless reckoning from which there is no possible mitigation, no chance to plead and nowhere to hide. No sleuth will arrive to interpret the clues, apprehend the villain and restore order, and the only thing you can do is try desperately to survive. Cosy is the very last thing it is. It also struck me that this is a novel of its time. Written and published in 1939, as the world was about to be precipitated into another cataclysmic war, the story felt on the very edge of the chaos and slaughter of the Second World War and, simultaneously, shockingly contemporary. It also felt profoundly subversive.

Following And Then There Were None, I was asked to read The Witness for the Prosecution for a two-hour BBC adaptation. It is a story of sex, money, deceit, performance and murder with the most glorious, sleight-of-hand twist. It has all the elements of classic Noir – murky motives, an enigmatic femme fatale and a seemingly decent man drawn deep into the web. It is set (as are many of the stories in this collection) in the deeply divided 1920s, an era of giddy hedonistic excess, champagne, shingled hair, the sizzle and thrill of jazz for some but grinding penury and want for most. It’s a world of grimy boarding houses, dank streets thick with chill fog, flickering gaslights and the cold clear light of the courtroom. The shadow of the First World War, with its seismic upheavals, ruptured certainties, scars and horrors, looms darkly. In the TV adaptation Leonard Vole, the penniless young man accused of seducing and manipulating the wealthy, indulgent Emily French into making her will in his favour, and then murdering her, tells his pedantic solicitor John Mayhew

that he hadn’t been able to ‘settle to anything, not since service’. This detail thrums with battle trauma. Romaine, a Viennese actress and the only person who can speak in Vole’s defence, is considered to have got her ‘hooks’ into Vole to get herself out of the scorched ruins of Europe. She is a ‘dangerous woman’, thinks Mayhew, ‘very dangerous.’ He has no idea.

The story is rife with the bat-squeaks of transgression. The relationship between Emily French and Leonard Vole that Vole describes as motherly could equally be perceived as sexual. Janet the maid is described as so consumed with loathing and jealousy that you wonder at the dynamic of the household that Vole becomes a part of. Even Mayhew, with his dry little cough and his pince-nez and his adherence to ‘normal procedure’, isn’t immune to transgression. He is fascinated by Romaine to the point of obsession. His stuffy legal language is abandoned for eroticism during her very public humiliation; her ‘exquisite body’, how she flames and flaunts herself ‘like a tropical flower’. You can’t help but feel how much he’s enjoying watching Romaine break while the rest of the court judges her. The scarlet woman – not so dangerous now. The twist, when it comes, explodes like a bomb. The law is flawed. Justice is entirely fallible, driven by emotion, and emotions are easily manipulated. It’s not the truth that matters, Christie seems to suggest, but performance. Performance is everything.