По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

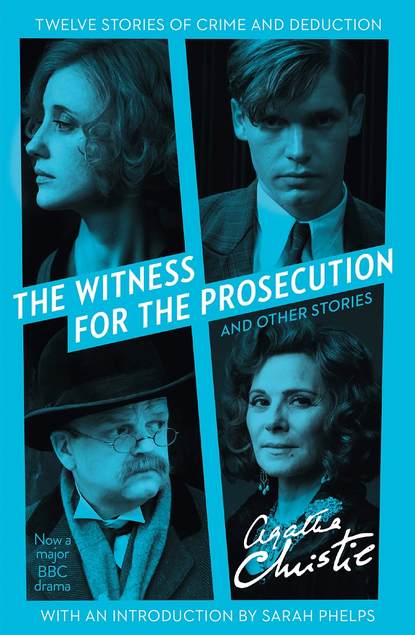

The Witness for the Prosecution: And Other Stories

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No—’ Again the constraint.

‘You will permit me to say,’ said the lawyer, ‘that I hardly understand your attitude in the matter.’

Vole flushed, hesitated, and then spoke.

‘I’ll make a clean breast of it. I was hard up, as you know. I hoped that Miss French might lend me some money. She was fond of me, but she wasn’t at all interested in the struggles of a young couple. Early on, I found that she had taken it for granted that my wife and I didn’t get on—were living apart. Mr Mayherne—I wanted the money—for Romaine’s sake. I said nothing, and allowed the old lady to think what she chose. She spoke of my being an adopted son for her. There was never any question of marriage—that must be just Janet’s imagination.’

‘And that is all?’

‘Yes—that is all.’

Was there just a shade of hesitation in the words? The lawyer fancied so. He rose and held out his hand.

‘Goodbye, Mr Vole.’ He looked into the haggard young face and spoke with an unusual impulse. ‘I believe in your innocence in spite of the multitude of facts arrayed against you. I hope to prove it and vindicate you completely.’

Vole smiled back at him.

‘You’ll find the alibi is all right,’ he said cheerfully.

Again he hardly noticed that the other did not respond.

‘The whole thing hinges a good deal on the testimony of Janet Mackenzie,’ said Mr Mayherne. ‘She hates you. That much is clear.’

‘She can hardly hate me,’ protested the young man.

The solicitor shook his head as he went out.

‘Now for Mrs Vole,’ he said to himself.

He was seriously disturbed by the way the thing was shaping.

The Voles lived in a small shabby house near Paddington Green. It was to this house that Mr Mayherne went.

In answer to his ring, a big slatternly woman, obviously a charwoman, answered the door.

‘Mrs Vole? Has she returned yet?’

‘Got back an hour ago. But I dunno if you can see her.’

‘If you will take my card to her,’ said Mr Mayherne quietly, ‘I am quite sure that she will do so.’

The woman looked at him doubtfully, wiped her hand on her apron and took the card. Then she closed the door in his face and left him on the step outside.

In a few minutes, however, she returned with a slightly altered manner.

‘Come inside, please.’

She ushered him into a tiny drawing-room. Mr Mayherne, examining a drawing on the wall, started up suddenly to face a tall pale woman who had entered so quietly that he had not heard her.

‘Mr Mayherne? You are my husband’s solicitor, are you not? You have come from him? Will you please sit down?’

Until she spoke he had not realized that she was not English. Now, observing her more closely, he noticed the high cheek-bones, the dense blue-black of the hair, and an occasional very slight movement of the hands that was distinctly foreign. A strange woman, very quiet. So quiet as to make one uneasy. From the very first Mr Mayherne was conscious that he was up against something that he did not understand.

‘Now, my dear Mrs Vole,’ he began, ‘you must not give way—’

He stopped. It was so very obvious that Romaine Vole had not the slightest intention of giving way. She was perfectly calm and composed.

‘Will you please tell me all about it?’ she said. ‘I must know everything. Do not think to spare me. I want to know the worst.’ She hesitated, then repeated in a lower tone, with a curious emphasis which the lawyer did not understand: ‘I want to know the worst.’

Mr Mayherne went over his interview with Leonard Vole. She listened attentively, nodding her head now and then.

‘I see,’ she said, when he had finished. ‘He wants me to say that he came in at twenty minutes past nine that night?’

‘He did come in at that time?’ said Mr Mayherne sharply.

‘That is not the point,’ she said coldly. ‘Will my saying so acquit him? Will they believe me?’

Mr Mayherne was taken aback. She had gone so quickly to the core of the matter.

‘That is what I want to know,’ she said. ‘Will it be enough? Is there anyone else who can support my evidence?’

There was a suppressed eagerness in her manner that made him vaguely uneasy.

‘So far there is no one else,’ he said reluctantly.

‘I see,’ said Romaine Vole.

She sat for a minute or two perfectly still. A little smile played over her lips.

The lawyer’s feeling of alarm grew stronger and stronger.

‘Mrs Vole—’ he began. ‘I know what you must feel—’

‘Do you?’ she said. ‘I wonder.’

‘In the circumstances—’

‘In the circumstances—I intend to play a lone hand.’

He looked at her in dismay.

‘But, my dear Mrs Vole—you are overwrought. Being so devoted to your husband—’

‘I beg your pardon?’

The sharpness of her voice made him start. He repeated in a hesitating manner:

‘Being so devoted to your husband—’