По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

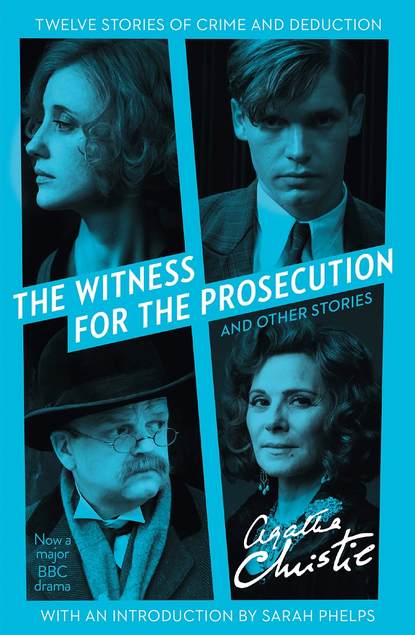

The Witness for the Prosecution: And Other Stories

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As the story proceeded, the feeling of the court which had, to begin with, been slightly favourable to the prisoner, now set dead against him. He himself sat with downcast head and moody air, as though he knew he were doomed.

Yet it might have been noted that her own counsel sought to restrain Romaine’s animosity. He would have preferred her to be a more unbiased witness.

Formidable and ponderous, counsel for the defence arose.

He put it to her that her story was a malicious fabrication from start to finish, that she had not even been in her own house at the time in question, that she was in love with another man and was deliberately seeking to send Vole to his death for a crime he did not commit.

Romaine denied these allegations with superb insolence.

Then came the surprising denouement, the production of the letter. It was read aloud in court in the midst of a breathless stillness.

Max, beloved, the Fates have delivered him into our hands! He has been arrested for murder—but, yes, the murder of an old lady! Leonard who would not hurt a fly! At last I shall have my revenge. The poor chicken! I shall say that he came in that night with blood upon him—that he confessed to me. I shall hang him, Max—and when he hangs he will know and realize that it was Romaine who sent him to his death. And then—happiness, Beloved! Happiness at last!

There were experts present ready to swear that the handwriting was that of Romaine Heilger, but they were not needed. Confronted with the letter, Romaine broke down utterly and confessed everything. Leonard Vole had returned to the house at the time he said, twenty past nine. She had invented the whole story to ruin him.

With the collapse of Romaine Heilger, the case for the Crown collapsed also. Sir Charles called his few witnesses, the prisoner himself went into the box and told his story in a manly straightforward manner, unshaken by cross-examination.

The prosecution endeavoured to rally, but without great success. The judge’s summing up was not wholly favourable to the prisoner, but a reaction had set in and the jury needed little time to consider their verdict.

‘We find the prisoner not guilty.’

Leonard Vole was free!

Little Mr Mayherne hurried from his seat. He must congratulate his client.

He found himself polishing his pince-nez vigorously, and checked himself. His wife had told him only the night before that he was getting a habit of it. Curious things habits. People themselves never knew they had them.

An interesting case—a very interesting case. That woman, now, Romaine Heilger.

The case was dominated for him still by the exotic figure of Romaine Heilger. She had seemed a pale quiet woman in the house at Paddington, but in court she had flamed out against the sober background. She had flaunted herself like a tropical flower.

If he closed his eyes he could see her now, tall and vehement, her exquisite body bent forward a little, her right hand clenching and unclenching itself unconsciously all the time.

Curious things, habits. That gesture of hers with the hand was her habit, he supposed. Yet he had seen someone else do it quite lately. Who was it now? Quite lately—

He drew in his breath with a gasp as it came back to him. The woman in Shaw’s Rents …

He stood still, his head whirling. It was impossible—impossible—Yet, Romaine Heilger was an actress.

The KC came up behind him and clapped him on the shoulder.

‘Congratulated our man yet? He’s had a narrow shave, you know. Come along and see him.’

But the little lawyer shook off the other’s hand.

He wanted one thing only—to see Romaine Heilger face to face.

He did not see her until some time later, and the place of their meeting is not relevant.

‘So you guessed,’ she said, when he had told her all that was in his mind. ‘The face? Oh! that was easy enough, and the light of that gas jet was too bad for you to see the make-up.’

‘But why—why—’

‘Why did I play a lone hand?’ She smiled a little, remembering the last time she had used the words.

‘Such an elaborate comedy!’

‘My friend—I had to save him. The evidence of a woman devoted to him would not have been enough—you hinted as much yourself. But I know something of the psychology of crowds. Let my evidence be wrung from me, as an admission, damning me in the eyes of the law, and a reaction in favour of the prisoner would immediately set in.’

‘And the bundle of letters?’

‘One alone, the vital one, might have seemed like a—what do you call it?—put-up job.’

‘Then the man called Max?’

‘Never existed, my friend.’

‘I still think,’ said little Mr Mayherne, in an aggrieved manner, ‘that we could have got him off by the—er—normal procedure.’

‘I dared not risk it. You see, you thought he was innocent—’

‘And you knew it? I see,’ said little Mr Mayherne.

‘My dear Mr Mayherne,’ said Romaine, ‘you do not see at all. I knew—he was guilty!’

Accident (#ulink_cd870f69-7b43-5a7c-b0cb-698954d028bf)

‘… And I tell you this—it’s the same woman—not a doubt of it!’

Captain Haydock looked into the eager, vehement face of his friend and sighed. He wished Evans would not be so positive and so jubilant. In the course of a career spent at sea, the old sea captain had learned to leave things that did not concern him well alone. His friend, Evans, late C.I.D. Inspector, had a different philosophy of life. ‘Acting on information received—’ had been his motto in early days, and he had improved upon it to the extent of finding out his own information. Inspector Evans had been a very smart, wide-awake officer, and had justly earned the promotion which had been his. Even now, when he had retired from the force, and had settled down in the country cottage of his dreams, his professional instinct was still active.

‘Don’t often forget a face,’ he reiterated complacently. ‘Mrs Anthony—yes, it’s Mrs Anthony right enough. When you said Mrs Merrowdene—I knew her at once.’

Captain Haydock stirred uneasily. The Merrowdenes were his nearest neighbours, barring Evans himself, and this identifying of Mrs Merrowdene with a former heroine of a cause célèbre distressed him.

‘It’s a long time ago,’ he said rather weakly.

‘Nine years,’ said Evans, accurately as ever. ‘Nine years and three months. You remember the case?’

‘In a vague sort of way.’

‘Anthony turned out to be an arsenic eater,’said Evans, ‘so they acquitted her.’

‘Well, why shouldn’t they?’

‘No reason in the world. Only verdict they could give on the evidence. Absolutely correct.’

‘Then that’s all right,’ said Haydock. ‘And I don’t see what we’re bothering about.’