По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

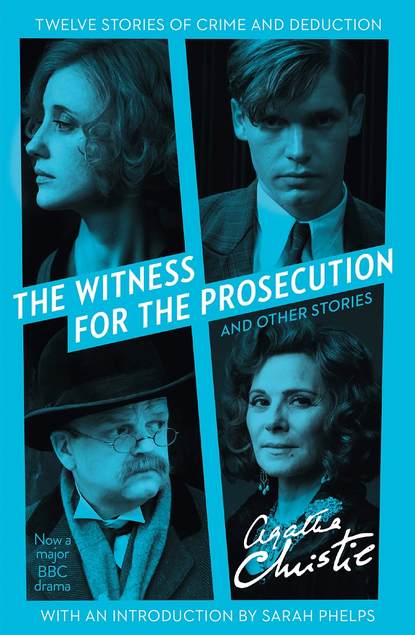

The Witness for the Prosecution: And Other Stories

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It was clever—it was damnably clever. He would be able to prove nothing. She counted on his not suspecting—simply because it was ‘so soon’. A woman of lightning rapidity of thought and action.

He drew a deep breath and leaned forward.

‘Mrs Merrowdene, I’m a man of queer whims. Will you be very kind and indulge me in one of them?’

She looked inquiring but unsuspicious.

He rose, took the bowl from in front of her and crossed to the little table where he substituted it for the other. This other he brought back and placed in front of her.

‘I want to see you drink this.’

Her eyes met his. They were steady, unfathomable. The colour slowly drained from her face.

She stretched out her hand, raised the cup. He held his breath. Supposing all along he had made a mistake.

She raised it to her lips—at the last moment, with a shudder, she leant forward and quickly poured it into a pot containing a fern. Then she sat back and gazed at him defiantly.

He drew a long sigh of relief, and sat down again.

‘Well?’ she said.

Her voice had altered. It was slightly mocking—defiant.

He answered her soberly and quietly:

‘You are a very clever woman, Mrs Merrowdene. I think you understand me. There must be no—repetition. You know what I mean?’

‘I know what you mean.’

Her voice was even, devoid of expression. He nodded his head, satisfied. She was a clever woman, and she didn’t want to be hanged.

‘To your long life and to that of your husband,’ he said significantly, and raised his tea to his lips.

Then his face changed. It contorted horribly … he tried to rise—to cry out … His body stiffened—his face went purple. He fell back sprawling over his chair—his limbs convulsed.

Mrs Merrowdene leaned forward, watching him. A little smile crossed her lips. She spoke to him—very softly and gently.

‘You made a mistake, Mr Evans. You thought I wanted to kill George … How stupid of you—how very stupid.’

She sat there a minute longer looking at the dead man, the third man who had threatened to cross her path and separate her from the man she loved.

Her smile broadened. She looked more than ever like a madonna. Then she raised her voice and called:

‘George, George! … Oh, do come here! I’m afraid there’s been the most dreadful accident … Poor Mr Evans …’

The Fourth Man (#ulink_34badc09-1f13-5850-8a8f-afaf509a8812)

Canon Parfitt panted a little. Running for trains was not much of a business for a man of his age. For one thing his figure was not what it was and with the loss of his slender silhouette went an increasing tendency to be short of breath. This tendency the Canon himself always referred to, with dignity, as ‘My heart, you know!’

He sank into the corner of the first-class carriage with a sigh of relief. The warmth of the heated carriage was most agreeable to him. Outside the snow was falling. Lucky to get a corner seat on a long night journey. Miserable business if you didn’t. There ought to be a sleeper on this train.

The other three corners were already occupied, and noting this fact Canon Parfitt became aware that the man in the far corner was smiling at him in gentle recognition. He was a clean-shaven man with a quizzical face and hair just turning grey on the temples. His profession was so clearly the law that no one could have mistaken him for anything else for a moment. Sir George Durand was, indeed, a very famous lawyer.

‘Well, Parfitt,’ he remarked genially, ‘you had a run for it, didn’t you?’

‘Very bad for my heart, I’m afraid,’ said the Canon. ‘Quite a coincidence meeting you, Sir George. Are you going far north?’

‘Newcastle,’ said Sir George laconically. ‘By the way,’ he added, ‘do you know Dr Campbell Clark?’

The man sitting on the same side of the carriage as the Canon inclined his head pleasantly.

‘We met on the platform,’ continued the lawyer. ‘Another coincidence.’

Canon Parfitt looked at Dr Campbell Clark with a good deal of interest. It was a name of which he had often heard. Dr Clark was in the forefront as a physician and mental specialist, and his last book, The Problem of the Unconscious Mind, had been the most discussed book of the year.

Canon Parfitt saw a square jaw, very steady blue eyes and reddish hair untouched by grey, but thinning rapidly. And he received also the impression of a very forceful personality.

By a perfectly natural association of ideas the Canon looked across to the seat opposite him, half-expecting to receive a glance of recognition there also, but the fourth occupant of the carriage proved to be a total stranger—a foreigner, the Canon fancied. He was a slight dark man, rather insignificant in appearance. Huddled in a big overcoat, he appeared to be fast asleep.

‘Canon Parfitt of Bradchester?’ inquired Dr Campbell Clark in a pleasant voice.

The Canon looked flattered. Those ‘scientific sermons’ of his had really made a great hit—especially since the Press had taken them up. Well, that was what the Church needed—good modern up-to-date stuff.

‘I have read your book with great interest, Dr Campbell Clark,’ he said. ‘Though it’s a bit technical here and there for me to follow.’

Durand broke in.

‘Are you for talking or sleeping, Canon?’ he asked. ‘I’ll confess at once that I suffer from insomnia and that therefore I’m in favour of the former.’

‘Oh! certainly. By all means,’ said the Canon. ‘I seldom sleep on these night journeys, and the book I have with me is a very dull one.’

‘We are at any rate a representative gathering,’ remarked the doctor with a smile. ‘The Church, the Law, the Medical Profession.’

‘Not much we couldn’t give an opinion on between us, eh?’ laughed Durand. ‘The Church for the spiritual view, myself for the purely worldly and legal view, and you, Doctor, with the widest field of all, ranging from the purely pathological to the—super-psychological! Between us three we should cover any ground pretty completely, I fancy.’

‘Not so completely as you imagine, I think,’ said Dr Clark. ‘There’s another point of view, you know, that you left out, and that’s rather an important one.’

‘Meaning?’ queried the lawyer.

‘The point of view of the Man in the Street.’

‘Is that so important? Isn’t the Man in the Street usually wrong?’

‘Oh! almost always. But he has the thing that all expert opinion must lack—the personal point of view. In the end, you know, you can’t get away from personal relationships. I’ve found that in my profession. For every patient who comes to me genuinely ill, at least five come who have nothing whatever the matter with them except an inability to live happily with the inmates of the same house. They call it everything—from housemaid’s knee to writer’s cramp, but it’s all the same thing, the raw surface produced by mind rubbing against mind.’

‘You have a lot of patients with “nerves”, I suppose,’ the Canon remarked disparagingly. His own nerves were excellent.

‘Ah! and what do you mean by that?’ The other swung round on him, quick as a flash. ‘Nerves! People use that word and laugh after it, just as you did. “Nothing the matter with so and so,” they say. “Just nerves.” But, good God, man, you’ve got the crux of everything there! You can get at a mere bodily ailment and heal it. But at this day we know very little more about the obscure causes of the hundred and one forms of nervous disease than we did in—well, the reign of Queen Elizabeth!’