По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

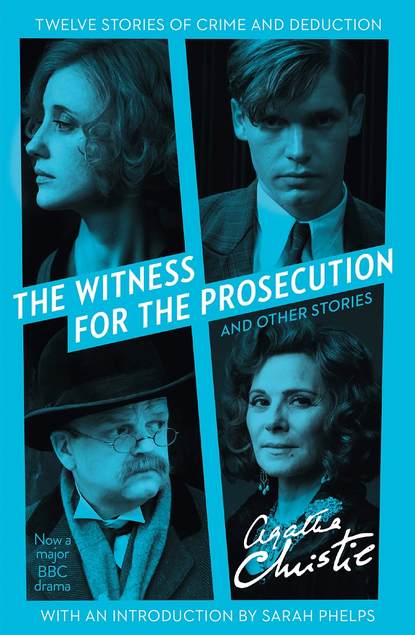

The Witness for the Prosecution: And Other Stories

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Sir George Durand merely composed himself in an attitude of keen attention.

‘My name, gentlemen,’ began their strange travelling companion, ‘is Raoul Letardeau. You have spoken just now of an English lady, Miss Slater, who interested herself in works of charity. I was born in that Brittany fishing village and when my parents were both killed in a railway accident it was Miss Slater who came to the rescue and saved me from the equivalent of your English workhouse. There were some twenty children under her care, girls and boys. Amongst these children were Felicie Bault and Annette Ravel. If I cannot make you understand the personality of Annette, gentlemen, you will understand nothing. She was the child of what you call a “fille de joie” who had died of consumption abandoned by her lover. The mother had been a dancer, and Annette, too, had the desire to dance. When I saw her first she was eleven years old, a little shrimp of a thing with eyes that alternately mocked and promised—a little creature all fire and life. And at once—yes, at once—she made me her slave. It was “Raoul, do this for me.” “Raoul, do that for me.” And me, I obeyed. Already I worshipped her, and she knew it.

‘We would go down to the shore together, we three—for Felicie would come with us. And there Annette would pull off her shoes and stockings and dance on the sand. And then when she sank down breathless, she would tell us of what she meant to do and to be.

‘“See you, I shall be famous. Yes, exceedingly famous. I will have hundreds and thousands of silk stockings—the finest silk. And I shall live in an exquisite apartment. All my lovers shall be young and handsome as well as being rich. And when I dance all Paris shall come to see me. They will yell and call and shout and go mad over my dancing. And in the winters I shall not dance. I shall go south to the sunlight. There are villas there with orange trees. I shall have one of them. I shall lie in the sun on silk cushions, eating oranges. As for you, Raoul, I will never forget you, however rich and famous I shall be. I will protect you and advance your career. Felicie here shall be my maid—no, her hands are too clumsy. Look at them, how large and coarse they are.”

‘Felicie would grow angry at that. And then Annette would go on teasing her.

‘“She is so ladylike, Felicie—so elegant, so refined. She is a princess in disguise—ha, ha.”

‘“My father and mother were married, which is more than yours were,” Felicie would growl out spitefully.

‘“Yes, and your father killed your mother. A pretty thing, to be a murderer’s daughter.”

‘“Your father left your mother to rot,” Felicie would rejoin.

‘“Ah! yes.” Annette became thoughtful. “Pauvre Maman. One must keep strong and well. It is everything to keep strong and well.”

‘“I am as strong as a horse,” Felicie boasted.

‘And indeed she was. She had twice the strength of any other girl in the Home. And she was never ill.

‘But she was stupid, you comprehend, stupid like a brute beast. I often wondered why she followed Annette round as she did. It was, with her, a kind of fascination. Sometimes, I think, she actually hated Annette, and indeed Annette was not kind to her. She jeered at her slowness and stupidity, and baited her in front of the others. I have seen Felicie grow quite white with rage. Sometimes I have thought that she would fasten her fingers round Annette’s neck and choke the life out of her. She was not nimble-witted enough to reply to Annette’s taunts, but she did learn in time to make one retort which never failed. That was a reference to her own health and strength. She had learned (what I had always known) that Annette envied her her strong physique, and she struck instinctively at the weak spot in her enemy’s armour.

‘One day Annette came to me in great glee.

‘“Raoul,” she said. “We shall have fun today with that stupid Felicie. We shall die of laughing.”

‘“What are you going to do?”

‘“Come behind the little shed, and I will tell you.”

‘It seemed that Annette had got hold of some book. Part of it she did not understand, and indeed the whole thing was much over her head. It was an early work on hypnotism.

‘“A bright object, they say. The brass knob of my bed, it twirls round. I made Felicie look at it last night. ‘Look at it steadily,’ I said. ‘Do not take your eyes off it.’ And then I twirled it. Raoul, I was frightened. Her eyes looked so queer—so queer. ‘Felicie, you will do what I say always,’ I said. ‘I will do what you say always, Annette,’ she answered. And then—and then—I said: ‘Tomorrow you will bring a tallow candle out into the playground at twelve o’clock and start to eat it. And if anyone asks you, you will say that is it the best galette you ever tasted.’ Oh! Raoul, think of it!”

‘“But she’ll never do such a thing,” I objected.

‘“The book says so. Not that I can quite believe it—but, oh! Raoul, if the book is all true, how we shall amuse ourselves!”

‘I, too, thought the idea very funny. We passed word round to the comrades and at twelve o’clock we were all in the playground. Punctual to the minute, out came Felicie with a stump of candle in her hand. Will you believe me, Messieurs, she began solemnly to nibble at it? We were all in hysterics! Every now and then one or other of the children would go up to her and say solemnly: “It is good, what you eat there, eh, Felicie?” And she would answer: “But, yes, it is the best galette I ever tasted.” And then we would shriek with laughter. We laughed at last so loud that the noise seemed to wake up Felicie to a realization of what she was doing. She blinked her eyes in a puzzled way, looked at the candle, then at us. She passed her hand over her forehead.

‘“But what is it that I do here?” she muttered.

‘“You are eating a candle,” we screamed.

‘“I made you do it. I made you do it,” cried Annette, dancing about.

‘Felicie stared for a moment. Then she went slowly up to Annette.

‘“So it is you—it is you who have made me ridiculous? I seem to remember. Ah! I will kill you for this.”

‘She spoke in a very quiet tone, but Annette rushed suddenly away and hid behind me.

‘“Save me, Raoul! I am afraid of Felicie. It was only a joke, Felicie. Only a joke.”

‘“I do not like these jokes,” said Felicie. “You understand? I hate you. I hate you all.”

‘She suddenly burst out crying and rushed away.

‘Annette was, I think, scared by the result of her experiment, and did not try to repeat it. But from that day on, her ascendancy over Felicie seemed to grow stronger.

‘Felicie, I now believe, always hated her, but nevertheless she could not keep away from her. She used to follow Annette around like a dog.

‘Soon after that, Messieurs, employment was found for me, and I only came to the Home for occasional holidays. Annette’s desire to become a dancer was not taken seriously, but she developed a very pretty singing voice as she grew older and Miss Slater consented to her being trained as a singer.

‘She was not lazy, Annette. She worked feverishly, without rest. Miss Slater was obliged to prevent her doing too much. She spoke to me once about her.

‘“You have always been fond of Annette,” she said. “Persuade her not to work too hard. She has a little cough lately that I do not like.”

‘My work took me far afield soon afterwards. I received one or two letters from Annette at first, but then came silence. For five years after that I was abroad.

‘Quite by chance, when I returned to Paris, my attention was caught by a poster advertising Annette Ravelli with a picture of the lady. I recognized her at once. That night I went to the theatre in question. Annette sang in French and Italian. On the stage she was wonderful. Afterwards I went to her dressing-room. She received me at once.

‘“Why, Raoul,” she cried, stretching out her whitened hands to me. “This is splendid. Where have you been all these years?”

‘I would have told her, but she did not really want to listen.’

‘“You see, I have very nearly arrived!”

‘She waved a triumphant hand round the room filled with bouquets.

‘“The good Miss Slater must be proud of your success.”

‘“That old one? No, indeed. She designed me, you know, for the Conservatoire. Decorous concert singing. But me, I am an artist. It is here, on the variety stage, that I can express myself.”

‘Just then a handsome middle-aged man came in. He was very distinguished. By his manner I soon saw that he was Annette’s protector. He looked sideways at me, and Annette explained.

‘“A friend of my infancy. He passes through Paris, sees my picture on a poster et voilà!”

‘The man was then very affable and courteous. In my presence he produced a ruby and diamond bracelet and clasped it on Annette’s wrist. As I rose to go, she threw me a glance of triumph and a whisper.

‘“I arrive, do I not? You see? All the world is before me.”

‘But as I left the room, I heard her cough, a sharp dry cough. I knew what it meant, that cough. It was the legacy of her consumptive mother.

‘I saw her next two years later. She had gone for refuge to Miss Slater. Her career had broken down. She was in a state of advanced consumption for which the doctors said nothing could be done.