По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

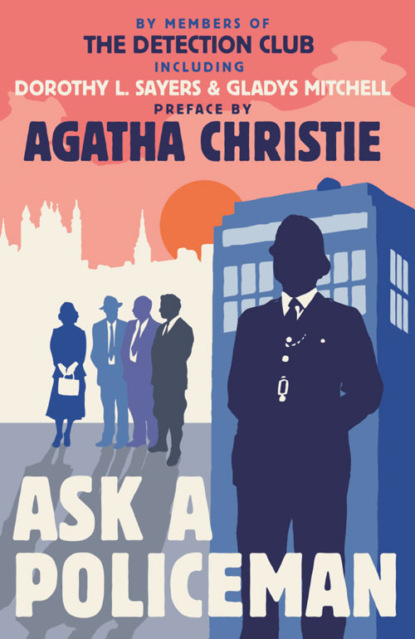

Ask a Policeman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

ASK A DETECTIVE WRITER

By MARTIN EDWARDS

ASK A POLICEMAN, first published in 1933, was the fourth in a sequence of collaborative mysteries produced in quick succession by members of the Detection Club. The Club was set up three years before this book was written, as an elite and rather secretive social network of leading detective novelists. It continues to flourish to this day, although current members include prominent thriller and espionage writers as well as specialists in the whodunit.

Ask a Policeman followed two radio serials, Behind the Screen and The Scoop, and a full-length detective novel, The Floating Admiral. These collective ventures generated enough revenue for the Club to rent premises in Soho, where, as Dorothy L. Sayers put it, members convened “chiefly for the purpose of eating dinners together and of talking illimitable shop.”

In the early Thirties, detective fiction was hugely popular, and many writers treated the detective story as a game in which they pitted their wits against their readers’. It was supposed to be important to “play fair”. Father Ronald Knox, a founder member of the Club, went so far as to devise a jokey Decalogue of ten commandments for the genre (“not more than one secret room or passage is allowable”, for instance)—which he and his colleagues were happy to break whenever it suited them.

Anthony Berkeley, who organized the dinner meetings that led to the foundation of the Club, and Dorothy L. Sayers, a towering presence in its ranks, headed a group of talented crime writers who became increasingly determined to explore criminal psychology and write novels of literary merit. Yet they too relished the intellectual exercise of creating elaborate puzzles.

Writing a round-robin mystery presents a variety of challenges for any team of authors, and Club members had to decide how to top the success of The Floating Admiral. Their answer was to come up with a fresh concept—they would write a story in which they exchanged detectives with each other. This gimmick afforded contributors the chance to poke fun at the genre, and at the quirks of their colleagues’ most famous sleuths. But transforming the idea into a readable story was bound to prove complex, with each contributor in turn needing plenty of space to develop the narrative in a distinctive way. This explains why, although 13 members provided ingredients for the mix in The Floating Admiral, just half a dozen created Ask a Policeman.

The original dust jacket blurb captured the gleeful spirit of the enterprise:

“Here is something delightfully new in ‘thrills’—a story which combines the interest of detection with the fun of parody. A problem is propounded; ingenious, and, for the solvers, malicious, and in itself a parody of a thousand and one detective stories. A great newspaper proprietor dies in his study, and suspicion falls upon an Archbishop, a Secretary, a Police Commissioner, and the Chief Whip of the political party in power. There is, too, a Mysterious Lady. What, then, can the Home Secretary do but call in the Amateur Experts? There are four of them; each takes a hand and each produces a different solution.”

The industrious and prolific John Rhode set the scene in a long introductory section. Rhode was the main pen-name of Cecil John Street (1884–1965), a former army officer who had won the Military Cross. His most famous detective was Dr. Lancelot Priestley, a rather severe intellectual who featured in a long line of novels but is absent here. Rhode was an efficient plot-builder, and created the perfect victim, a tyrannical media mogul whom every other character in the story seemed to have a possible motive to kill. In keeping with the fashion of the time, a plan of the scene of the crime was included.

The story was introduced by an exchange of letters between Rhode and Milward Kennedy. Kennedy (1894–1968) also concealed his identity under several pseudonyms—his real name was Milward Rodon Kennedy Burge. He worked in Military Intelligence during the First World War, and was awarded the Croix de Guerre prior to taking up a career in diplomacy. Like Anthony Berkeley, he wanted to push out the boundaries of the detective story, and several of his books experiment with the form. None of his characters, however, appeared in more than two books, and the absence of a series detective may help to explain why his fame did not last. To Kennedy fell the unenviable task of tying up the loose ends of the story, and one of the in-jokes of this book is that he gave the job of making sense of the case that had taxed Lord Peter Wimsey and others to a character who was, like himself, a civil servant. Another is his tongue-in-cheek admission to breaking the “Rules to which my fellow-members of the Detection Club always, and I on all occasions but this, make it a point of honour to adhere”.

Once Rhode had set the scene, the baton passed to Helen Simpson. Born in Sydney in 1897, she was both gifted and charismatic; Sayers, a close friend, said after Simpson’s untimely death from cancer in 1940, “I have never met anybody who equalled her in vivid personality and in the intense interest she brought into her contacts with people and things.” Simpson tried her hand at poetry and plays before collaborating with Clemence Dane on Enter Sir John, which introduced Sir John Samaurez, the actor-manager of the Sheridan Theatre. Sir John sets about clearing the name of a young actress who has been charged with murder, and makes such a success of the task that, by the time Ask a Policeman appeared, the two of them are husband and wife. Enter Sir John was turned into a film by Alfred Hitchcock called Murder! Simpson co-wrote two more books with Dane, as well as producing several solo novels, including Under Capricorn, which later became another Hitchcock movie. Turning to politics, Simpson was adopted as Liberal Parliamentary Candidate for the Isle of Wight before the cruel intervention of the disease that killed her. The energy, wit and skill with which, in this book, she tackles her portrayal of Gladys Mitchell’s detective, Mrs. Bradley, seem typical of how she approached everything in her life.

Gladys Mitchell had been elected to membership of the Club shortly before this book was written. She too admired Simpson, describing her in an interview with B.A. Pike as “brilliant, witty, charming and highly intellectual”; she even allowed Simpson to bestow a second forename, Adela, upon her detective. Mitchell (1901-1983), combined writing with a career as a schoolteacher; she introduced Mrs. Bradley in a convention-defying mystery called Speedy Death, and continued to write about her for more than half a century. Her books often contain bizarre elements, but she attracted a devoted band of readers, including Philip Larkin, who called her “the Great Gladys”. Mrs. Bradley, a psychiatrist and consultant psychologist to the Home Office, has the looks of a “sinister pterodactyl”, but when The Mrs. Bradley Mysteries aired on BBC Television in 1998-9, she was played by Diana Rigg, a casting decision so eccentric as to be worthy of Mitchell herself.

Anthony Berkeley was one of crime fiction’s leading innovators. His real name was Anthony Berkeley Cox (1893-1971), and he wrote a good many humorous articles for magazines before introducing Roger Sheringham in The Layton Court Mystery, which was at first published anonymously. Writing as Francis Iles, he produced ground-breaking—and deeply cynical—novels about crime, notably Malice Aforethought and Before the Fact; the latter was filmed by Hitchcock as Suspicion. The Sheringham mysteries often feature puzzles with ingenious multiple solutions; the most dazzling example, The Poisoned Chocolates Case, is name-checked by Sayers in this book. Berkeley liked to explore dilemmas about justice, and was intrigued by the idea of the fallible sleuth. So in his work, murderers sometimes escape unpunished, Sheringham does not always come up with the right solution to the mystery, and tricky plot devices are allied to a sharp, ironic wit. To take on the job of writing about Sayers’ hero Lord Peter required some courage, as she was a formidable woman, held in awe by many of her Detection Club colleagues. But Berkeley rose to the challenge, and he captured Wimsey brilliantly, in a chapter that offers one of the finest of all Golden Age parodies as well as a clever solution to the problem Rhode had posed. Gladys Mitchell—who liked Berkeley rather more than Sayers—recalled in her old age that “Anthony’s manipulation of Lord Peter Wimsey caused the massive lady anything but pleasure”, but although in later years, these two strong, and often intimidating personalities came increasingly into conflict, it is hard to believe that Sayers failed to appreciate the flair displayed in Berkeley’s contribution to Ask a Policeman.

At the time this book was written, Sayers was taking the detective story in a new direction. Wimsey had started out as little more than a caricature, albeit a caricature portrayed with affectionate humour. In Whose Body?, published in 1923, we are told that his “long amiable face looked as if it had generated spontaneously from his top hat, as white maggots breed from Gorgonzola”. But once he met and fell in love with Harriet Vane, a detective novelist convicted of murder (was Sir John Samaurez’ first case the inspiration for this idea?), he grew as a character. Sayers’ depiction of his relationship with Harriet set the pattern for succeeding generations of crime writers, who preferred to create serious and believable protagonists with lives that change as the years pass, rather than ‘supermen’ detectives in the mould of Sherlock Holmes. Sayers (1893-1957) was self-consciously intellectual, and in her only non-series novel, The Documents in the Case, co-written with Robert Eustace, musings on the nature of life were integral to the plot. Sayers was dissatisfied with the end product, but her very attempt at such an ambitious undertaking showed that the genre had much more to offer than glorified crossword puzzles. In her chapter for Ask a Policeman, Sayers renders Sheringham effectively, with a neat joke when he overhears two employees of the late Lord Comstock being rude about him, and if the solution she puts forward is not quite as compelling as Berkeley’s, perhaps that underlines her increasing focus on characterisation as opposed to mere puzzle-making.

After the start of the Second World War, however, she turned her attention away from crime writing, focusing on the translation of Dante, and writing about religious subjects. Similarly, Berkeley and Kennedy began to concentrate on reviewing rather than producing novels. But all three of them remained associated with the Detection Club, with Sayers holding the office of President from 1948 until her death.

Agatha Christie, who had participated in the first three Detection Club collaborations, sat this one out. However, it is a real pleasure to be able to include here a delightful essay she wrote about her fellow practitioners—the first time it has appeared in volume form. She wrote it in 1945, at the request of the Ministry of Information, for publication in a Russian magazine. Presumably because she was confident that none of her peers in the Detection Club would come across her comments, she was quite candid.

So it is interesting to see that Christie disapproved of Wimsey’s transformation into a “handsome hero”, and damned Rhode’s prose style with faint praise as “straightforward”, as well as to note her admiration for Anthony Berkeley’s ability to provide first class entertainment. But she also made it clear that the writers she mentioned were those at the top of their profession. Today, though, not only are the books of H.C. Bailey, Rhode, Kennedy and many of their contemporaries forgotten by everyone except a small band of enthusiasts, surprisingly little is known about most of the Detection Club members themselves. I was honoured to be appointed as the first archivist of the Club—although the fact that the official archives are more or less non-existent is somehow typical of this unusual and mysterious institution. Its members—not just the usual suspects in Christie and Sayers, but also A.A. Milne and Baroness Orczy, who in addition to their detective stories were the creators respectively of Winnie-the-Pooh and the Scarlet Pimpernel—played a much more significant part in developing popular culture in the twentieth century than has so far been recognized. Frustratingly, no minutes of meetings appear to have survived, and some of the reminiscences of early members are classics of unreliable narration. So the challenge of discovering more about the early days of the Club, and the lives of its members, is almost as fascinating as many of those Golden Age puzzles

Ask a Policeman is, when all is said and done, a period piece. Kennedy’s solution does not really “play fair” with the reader, but the book is laden with charm as well as humour, and its reappearance is as welcome as it is overdue. Howard Haycraft, a noted American historian of the genre, hailed this book as “a matchless tour de force”, and its success prompted plenty of other writers to parody the classic detective story. But few of them achieved such enjoyable results as the six members of the Detection Club who combined to create this lively entertainment.

PREFACE

DETECTIVE WRITERS IN ENGLAND

BY AGATHA CHRISTIE

WHAT kind of people read detective stories and why? Invariably, I think, the busy people, the workers of the world. Highly placed men in the scientific world, even if they read nothing else, seem to have time for a detective story; perhaps because a detective story is complete relaxation, an escape from the realism of everyday life. It has, too, the tonic value of a puzzle—a challenge to the ingenuity. It sharpens your wits—makes you mentally alert. To follow a detective story closely you need concentration. To spot the criminal needs acumen and good reasoning powers. It has also a sporting interest and is much less expensive than betting on horses or gambling at cards! Its ethical background is usually sound. Very very rarely is the criminal the hero of the book! Society unites to hunt him down, and the reader can have all the fun of the chase without moving from a comfortable armchair.

Before speaking of present day English writers, I must first pay tribute to Conan Doyle, the pioneer of detective writing, with his two great creations Sherlock Holmes and Watson—Watson perhaps the greater creation of the two. Holmes after all has his properties, his violin, his dressing gown, his cocaine etc., whereas Watson has just himself—lovable, obtuse, faithful, maddening, guaranteed to be always wrong, and perpetually in a state of admiration! How badly we all need a Watson in our lives!

Most detective writing since then has been modelled roughly on the same structure. The detective is the “central character”. But there has come to be something too artificial about a “private investigator”. The essence of a detective story is that it shall be “natural” in its setting and characters. My own Hercule Poirot is often somewhat of an embarrassment to me—not in himself, but in the calling of his life. Would anyone go and “consult” him? One feels not. So, more and more, his entry into a murder drama has to be fortuitous. My Miss Marple is more happily placed—an elderly gossipy lady in a small village, who pokes her nose into all that does or does not concern her, and draws deductions based on years of experience of human nature.

At the present day, I should call Margery Allingham one of the foremost writers of detective fiction. Not only does she write excellent English, but her drawing of character is masterly and she has wonderful power in creating atmosphere. You can feel the sinister influences behind the scenes, and her characters live on in your memory long after you have put the book away: the grim autocrat Mrs. Faraday of Police at the Funeral; the kindly and lovable “belle” in Death of a Ghost; Jimmy Sutane, the sad faced dancer with the twinkling feet. They are unusual but real personalities, vividly interesting. And through the books moves “Mr. Campion”, apparently vacuous, actually keenly acute, and with him the faithful Lugg (in whom, alas, I never can quite believe!) The pleasant negative inconsequence of Campion makes a dramatic contrast with the undercurrent of suspicion and fear that grows to a climax—particularly is this so in Flowers for the Judge. Sometimes, one feels, Margery Allingham is inclined to subordinate plot to characters. She is so interested in them that the denouement of the crime sometimes comes rather flatly as inevitable, rather than as a surprising bombshell.

Dorothy Sayers, alas, has wearied of the detective story and has turned her attention elsewhere. We all regret it for she was such an exceptionally good detective story writer and a delightfully witty one. Her earlier books Whose Body?, Unnatural Death and The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club are decidedly her best, having greater simplicity and more “punch” to them. Also her detective “Lord Peter Wimsey”, whose face was originally piquantly described as “emerging from his top hat like a maggot emerging from a gorgonzola cheese”, became through the course of years merely a “handsome hero”, and admirers of his early prowess can hardly forgive his attachment to, and lengthy courtship of, a tiresome young woman called Harriet. One had hoped that, once married to her, he would resume his old form, but Lord Peter remains an example of a good man spoilt.

Not so Mr. Fortune, H.C. Bailey’s great creation. Reggie Fortune is always the same, and marriage to a discreet and charming wife has left his incisive character untouched. The stories stand or fall by Mr. Fortune. It is not the cases themselves but Mr. Fortune’s handling of them wherein lies the fascination. For Mr. Fortune is, undeniably, a great man. Now to label a man a great man and then write about him and show him to be a great man is a supreme literary feat! A noted surgeon and consultant to the Home Office, Reggie Fortune’s handling of his problems is like a surgical operation. Where all is apparently straightforward, he feels, probes, notes some tiny fact that a complacent police official has swept aside, and then he cuts down to the heart of the trouble. His method is the method of the knife, ruthless and incisive. His rudeness to the wretched Lomas (Assistant Commissioner of Police) is unbelievable—and leads one to speculate whether one day worm Lomas will turn and murder Mr. Fortune!

H.C. Bailey’s longer books are not so satisfactory as his shorter stories. All the characters are inclined to speak a special Baileyesque language of their own—a clear clipped jargon. This is effective in short doses as the atmosphere of the operating theatre. But the atmosphere of an operating theatre is essentially artificial—created deliberately for specific purposes. It cannot be prolonged into a picture of daily life. Some of the best of the Fortune stories show the deduction of a whole malignant growth from one small isolated incident. For instance, the discovery of a couple of withered leaves in a woman’s handbag, recognized by Mr. Fortune as Arctic Willow, cause him to inquire into an apparently satisfactory case of suicide.

Fat, lazy, incredibly greedy (his delight in cream and jam for tea make tantalizing reading in war days!), underneath Fortune’s smiling exterior there is cold steel. Reggie Fortune is for Justice—merciless and inexorable justice. His pity and indignation are aroused by the victims—in execution he is as ruthless as his own knife.

John Dickson Carr (or Carter Dickson, for they are one and the same) is a master magician. I believe that only those who write detective stories themselves can really appreciate his marvellous sleight of hand. For that is what it is—he is the supreme conjurer, the King of the Art of Misdirection. Each of his books is a brilliant, fantastic, quite impossible conjuring trick.

“You watch my hands, ladies and gentlemen, you watch my sleeves, the hat is empty, nothing anywhere—Hey presto! A Rabbit!” He has, too, the gift of story telling, once you begin a book of his, you simply cannot put it down. As each chapter draws to a close, you see ahead a reasonable explanation, then, like Alice through the Looking Glass’s path, it seems to shake itself, and off it goes in a twist of fresh bewilderment. His characterization is not particularly good, his people talk in a way quite unlike life, his events are fantastic. It is all stagey—set behind footlights—but what a performance!

Carr’s penchant is for the impossible situation. He starts with that—either with the familiar “closed room”, or “closed circle” or with, as in the “Arabian Nights Mystery”, a setting of pure fantasy, with a set of people behaving apparently like lunatics. Then with a shake of the kaleidoscope you get the reason of it, all is quite normal—and then fresh impossibilities, fresh rationalisations. For some people, the twists of the plot may be too complicated. He can certainly be accused of occasionally loading the dice, but that can be forgiven for the brilliance with which it is done. The clues to the truth are so slight as to be almost unfair: one little sentence slipped into the middle of a tense situation; a mention of a car radiator on p.30 that does not agree with the same car’s radiator on p.180. Do you notice it? Of course not! Your eyes are riveted on a suspicious circumstance which you think only you have spotted. Misdirection, again.

A crowd of people are assembled round a dinner table in The Red Widow Murders. There is a sinister room in the house, nailed up for many years. Anyone who stays in it alone is found dead. A man goes in, locks himself in while the others wait outside. Every quarter of an hour they call to him and he replies—but when the door is opened the man is dead, in a room with locked shutters and no secret ways in or out—and, what is more, that man has been dead for over an hour. The impossible has happened! You never noticed a little descriptive phrase about the man at dinner; pale, nervous, eating nothing but soup … Your clue was there, in those four words.

Dickson Carr’s detective is the beer drinking Dr. Fell, Carter Dickson’s sleuth is Sir Henry Merrivale, the “old man”, a former chief of Military Intelligence. I much prefer him of the two—but it is the actual unfolding of the story that is the real strength of Dickson Carr’s genius. He is a male Scheherazade—and certainly no cruel Empress could order his execution until she had heard the next instalment!

Ngaio Marsh is another deservedly popular detective writer. Her style is amusing and her characterizations excellent. Surfeit of Lampreys was a delightful book, though perhaps one so enjoyed the Lamprey family that one rather forgot about the murder. Death in Ecstasy is a very clever picture of a little coterie of worshippers in a “New Religion” adroitly put over by the infamous Father Garnett. Artists in Crime is a good story of murder amongst a collection of painters. Both the atmosphere and the people are first rate.

Then there is the master of alibis, Freeman Wills Crofts. Inspector French is a kindly painstaking man who accomplishes his results by sheer hard work. If you like alibis, then you will enjoy the efforts of Inspector French. The Cask, one of his earliest books, is a model of its kind. A cask arrives at a business firm in London and is found to contain the body of a young woman. From there on you trace the cask back to its sender and forward again—there seems no loop hole, no possible opportunity for the cask to have been opened and the body substituted for the original piece of statuary. Nevertheless, there is a flaw and at last, slowly worried out, the truth emerges.

There are many other good detective writers—space forbids the mention of all of them. There is Michael Innes, a brilliant and witty writer. There is straightforward John Rhode with Dr. Priestley in charge. There is Gladys Mitchell with her fascinating Mrs. Bradley, ugly as a toad and armed with the latest up-to-date theories of psychology. And Austin Freeman’s books remain interesting examples of scientific methods of crime deduction.

I have chosen out for fullest description those writers whom I myself admire most and consider at the top of their profession. No collection would be complete without the mention of Anthony Berkeley, founder of the Detective Club, although he has, alas, been silent for many years. But what delightful books he has written. Detection and crime at its wittiest—all his stories are amusing, intriguing, and he is a master of the final twist, the surprise dénouement. Roger Sheridan, the slightly fatuous novelist, is his detective, though Roger is not always allowed to shine. He remains always the gifted amateur—hit or miss—but whichever way it is, the entertainment is first class.

And now, perhaps, a few words about myself. Since I have been writing detective stories for a quarter of a century and have some forty-odd novels to my credit, I may lay claim at least to being an industrious craftsman. A more aristocratic title was given to me by an American paper which dubbed me the “Duchess of Death”.

I have enjoyed writing detective stories, and I think the austerity and stern discipline that goes to making a ‘tight’ detective plot is good for one’s thought processes. It is the kind of writing that does not permit loose or slipshod thinking. It all has to dovetail, to fit in as part of a carefully constructed whole. You must have your blueprint first, and it needs really constructive thinking to make a workmanlike job of it.

Naturally one’s methods alter. I have become more interested as the years go on in the preliminaries of crime—the interplay of character upon character, the deep smouldering resentments and dissatisfactions that do not always come to the surface but which may suddenly explode into violence. I have written light-hearted murder stories, and serious crime stories, and technical extravaganzas like Ten Little Niggers [And Then There Were None]. I have laid a crime story in Ancient Egypt, and a murder play on a modern Nile steamer. I have had the conventional Body in the Library, and Bodies in Aeroplanes, and on Boats and in Trans-European Trains. Hercule Poirot has made quite a place for himself in the world and is regarded perhaps with more affection by outsiders than by his own creator! I would give one piece of advice to young detective writers. Be very careful what central character you create—you may have him with you for a very long time!

INTRODUCTION TO PART I

(a)

“DEAR JOHN RHODE,

“People ask me, when they find out (let me be honest, ‘when I tell them’) that I write detective stories, ‘Oh, how do you begin? Do you think of a Murder and then work it out, or do you think of a Solution and do it backwards?’ I suppose the question is inevitable; I have never discovered the answer.

“At the moment I’m in a peculiar position: I’ve thought of a title—’ Ask a Policeman.’ That ought to suggest a nice murder, surely? You know, with Cabinet Ministers, and Papal Nuncios, and Libraries, and all the rest of it.

“But the queer thing is, the title does nothing of the sort—to me: how does it strike you?

“Yours ever,

“MILWARD KENNEDY.”