По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

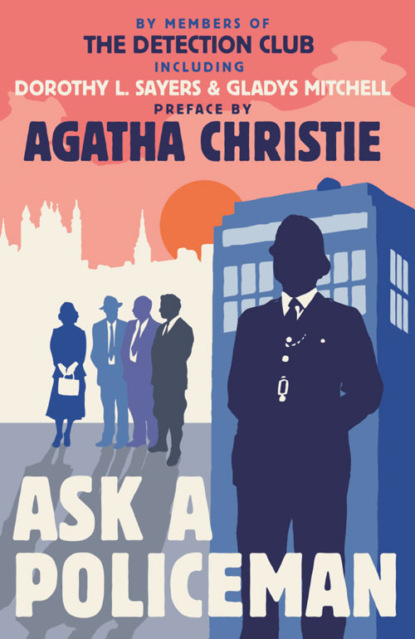

Ask a Policeman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(b)

“DEAR MILWARD KENNEDY,

“Yes, I know. I have never answered the question myself. I have come to the conclusion that writing detective stories is just like any other vice. The deed is done without one’s having any clear knowledge of the temptation which led up to it. But I must confess that I usually start with something more comprehensive than a title.

“I suppose your veiled suggestion is that I supply a plot to fit your title. But, honestly, to my simple mind ‘Ask a Policeman’ suggests the pawning of a watch—or are you too young to remember the old song?—rather than your galaxy of celebrities. Besides, I have never met a Papal Nuncio. I shouldn’t know what to say to him if I did. But I have seen an Archbishop—in the distance. And once I used to hold awestruck conversations with a Cabinet Minister, whose powers of invective I have always admired.

“So here is your plot. As you will see, you have a choice of many Policemen to interrogate as to its solution.

“Yours,

“JOHN RHODE.”

PART I

DEATH AT HURSLEY LODGE

BY JOHN RHODE

IT was impossible to tell, from the Home Secretary’s expression, exactly how the news had affected him. He was a big, heavy man, who looked much more like a country farmer than a Minister of the Crown. Punch was fond of caricaturing him in breeches and gaiters, with a pitchfork over his shoulder. You might have expected his position in the Cabinet to have been Minister of Agriculture.

But those who knew Sir Philip Brackenthorpe were well aware that a very keen brain was at work beneath his rather bucolic exterior. And that that brain was particularly active at this precise moment the Commissioner of Metropolitan Police had no doubt. The two were alone together in Sir Philip’s private room at the Home Office. Through the open windows came the muffled roar of the traffic in Whitehall, the only sound to break the silence which had followed the Commissioner’s terse statement.

“Comstock!” exclaimed Sir Philip at last, “The man lived on sensation, and it is only fitting that his death should provide the greatest sensation of all. Yes, you’re quite right, Hampton. I shall have to have all the facts at first hand. This business is bound to come up when the Cabinet meets to-morrow. Who have you got there?”

“Rather a crowd, I’m afraid, sir,” replied Sir Henry Hampton, “I don’t know whether you’ll care to see them all—”

“I’ll see anybody who’s got anything relevant to say about the affair. But, mind, I want evidence, and not speculation. But, before we start, I should like to see Littleton, since he’ll be primarily responsible for the investigations. He came here with you, of course?”

Hampton’s tall, gaunt frame imperceptibly stiffened. The question had been asked a good deal earlier than he had anticipated. It was devilish awkward, for Sir Philip was not the sort of person who could be put off with evasions. “Littleton was not in his office when the message came through to Scotland Yard just now, I’m sorry to say,” he replied simply.

No use going into details, thought Hampton. Littleton, the Assistant Commissioner in charge of the Criminal Investigation Department, might be expected to return at any minute now. He would find a message telling him to come at once to the Home Office. And then, as Hampton reflected grimly, he could tell his own story. And, if the amazing rumour which had reached the Commissioner as to his whereabouts was true, his story might prove particularly interesting.

Sir Philip must have guessed that Hampton was withholding something from him. “You are responsible for your own Department,” he said, with a touch of severity. “You will naturally give Littleton such instructions as you consider necessary. But I want to impress upon you that the death of a man like Comstock is not an everyday event. It will require, shall we say, special methods of investigation. And that for many reasons, which I need scarcely point out to you.”

From the far-away expression of his eyes, it seemed that Sir Philip was mentally addressing a larger and more important audience. Hampton wondered idly whether it was the Cabinet or the House of Commons that he was thinking of. The murder—if it was murder—of a man like Lord Comstock was an event of world-wide importance. The newspapers controlled by the millionaire journalist exerted an influence out of all proportion to their real value. Inspired by Comstock himself, they claimed at frequent intervals to be the real arbiters of the nation’s destiny at home and abroad. Governments might come and go, each with its own considered policy. The Comstock Press patronized, ignored, or attacked them, as suited Lord Comstock’s whim at the moment. His policy was fixed and invariable.

This may seem an astounding statement to those who remember how swiftly and how frequently the Daily Bugle changed its editorial opinions. But Lord Comstock’s policy was not concerned with the welfare of the State, or of anyone else but himself, for that matter. It was devoted with unswerving purpose to one single aim, the increase in value of his advertisement pages. The surest way to do this was to increase, circulation, to bamboozle the public into buying the organs of the Comstock Press. And nobody knew better than Lord Comstock that the surest way of luring the public was by a stunt, the more extravagant the better.

Stunts therefore followed one another with bewildering rapidity. Of those running at the moment, two had attracted special attention. To be successful, stunts must attack something or somebody, preferably so well established that it or he has become part of the ordinary person’s accepted scheme of things. Lord Comstock had selected Christianity as the first object of his attack.

But he was far too able a journalist merely to attack. His assault upon Christianity had nothing in common with the iconoclasm of the Bolshevists. Christianity must be abandoned, not because it was a menace to Socialism, but because the Christian civilization had manifestly failed. The economic slough of despond had demonstrated that, clearly enough. Christianity had swept away the conception of the Platonic Republic, with its single and logical solutions of all problems which could beset the Commonwealth. “Back to Paganism!” was the slogan, and the Daily Bugle devoted many columns daily to proving that by this means alone the existing economic depression could be finally cured.

One antagonist at a time, even so formidable an antagonist as Christianity, could not satisfy the restless spirit of Lord Comstock. He sought another and found it in the Metropolitan Police, his choice being influenced mainly by the implicit faith which that institution most justly inspired. Scotland Yard was the principal object of the invective of the Comstock Press. It was inefficient, ill-conducted, and corrupt. It must be reformed, root and branch. The crime experts of the Comstock Press, men who knew how to use their brains, were worth the whole of the C.I.D. and its elaborate machinery, which imposed so heavy and useless a burden upon the tax-payer.

Now and then it happened that a crime was committed, and no arrest followed. This was the opportunity of the Comstock Press. Without the slightest regard for the merits of the case, and safe in the knowledge that a Government Department cannot reply, the Daily Bugle, and its evening contemporary, the Evening Clarion, unloosed a flood of vituperation upon the C.I.D., from the Assistant Commissioner himself to his humblest subordinate. And the most recent instance of this—the echoes of the storm were still rumbling—was vividly in the Home Secretary’s mind as he sat thoughtfully drawing elaborate geometrical patterns upon his blotting paper.

In fact, the shadow of Lord Comstock lay heavily on both men, as they sat in the oppressive warmth of the June afternoon. It was as though his invisible presence lurked in the corner of the room, masterful, contemptuous, poisoning the air with the taint of falsehood. That at that very moment he lay dead in his own country retreat, Hursley Lodge, was a fact so incredible that it required time for its realization. Hence, perhaps, the silence which had once more fallen upon the room.

It was broken by Sir Philip. “Did you know the man personally?” he asked abruptly, without taking his eyes from the figures he was tracing.

“I’ve seen him often enough, and spoken to him once or twice;” replied the Commissioner; “but I can’t say that I knew him.”

“I knew him,” said Sir Philip slowly. From his manner it seemed as though he were more interested in his designs than in his subject. “At least, I knew as much about him as he cared for anyone to know. It wasn’t difficult. He had only one topic of conversation. With men, at least. I’ve been given to understand that his conversation with women was apt to be more intimate. And that was himself.”

With infinite care he drew a line joining two triangles apex to apex. He contemplated the result with evident satisfaction, then looked up, and continued more briskly. “He loved to talk about himself and his achievements, up to a point. You can guess the sort of thing. The contrast between what he was and what he became. You couldn’t help admiring the fellow as you listened, however much you disliked him. He was an able man in his own way, Hampton, there’s no getting away from that. An able man, and a strong man, with that innate ruthlessness which makes for success. You know how he started life, of course?”

“Pretty low down in the social scale, from all I’ve heard,” replied the Commissioner.

“His father worked in a mill somewhere up north. A very decent and respectable chap, I believe. Quite a different type from Comstock. Saved and scraped with only one object in view, to make a gentleman out of that scapegrace son of his. It’s a mercy he never lived to know how completely his efforts failed. Anyhow, he sent the lad to Blackminster Grammar School. Lord knows what sort of a figure he must have cut when he first went there. But he was head of the school before he left.”

“No lack of brains, even then, apparently,” remarked the Commissioner.

“No lack of brains, or of determination. But then comes a gap. Comstock disappears from sight—conversationally, I mean—after that. Nobody has ever heard him mention the intervening years. The rungs of the ladder are hidden from us. He reappears in a blaze of glory as Lord Comstock, reputed millionaire, and owner of heaven knows how many disreputable rags. Ambitious, too. Life’s work not yet accomplished, and all that sort of thing. And now you say he’s lying dead at that country place of his, Hursley Lodge. I’ve never seen it. Male visitors were not made welcome there, I’ve always understood.”

“Welcome or not, there were quite a crowd of them there this morning,” remarked the Commissioner grimly. “Only quite a small house, too.”

Sir Philip nodded. His reminiscent mood passed suddenly. “All right, bring them in,” he said. “Your own people first. The police, I mean. This chap who was called in first. I’ll leave you to get the story out of them.”

The Commissioner opened the door which led into the Private Secretary’s room beyond. He looked round sharply, hoping to see the truculent figure of the Assistant Commissioner among the group which stood there, nervous and ill at ease. A frown expressed his disappointment. He beckoned sharply to three men, standing by. In single file they followed him into Sir Philip’s presence.

Hampton introduced them curtly. “Chief Constable Shawford, Superintendent Churchill, sir. Both of the Yard. This is Superintendent Easton, of the local police.” Sir Philip glanced at the men in turn, nodded at each but said nothing beyond a curt “sit down,” addressed to them all in general. They obeyed—the lower the rank, the greater the distance maintained from the Home Secretary. The Commissioner at first occupied a large arm-chair touching the desk, but as the interview went on he ceased to have a regular station—he would sit one minute, stand the next, lean on the big desk, and almost promise (so it seemed to the inexperienced Easton) to whisk away the Home Secretary and occupy his chair. Sir Philip, picking up his pencil again, drew with more deliberation than skill, a large circle upon his blotting-paper.

“Easton’s district includes Hursley Lodge, sir,” the Commissioner began, without further preface. “He was at the police-station when a call was received that Lord Comstock had been found dead in his study. This was at 1.7 this afternoon.”

Sir Philip glanced at the clock on his desk. It was then 2.35 p.m.

“He drove at once to Hursley Lodge, and was received by Lord Comstock’s secretary, Mr. Mills, who took him straight up to the study. His story will be more easy to follow, sir, if you keep this plan in front of you.”

He placed a neatly-drawn diagram on the desk, and Sir Philip studied it curiously. “Where did this come from?” he asked.

“Easton brought it with him from Hursley Lodge, sir,” replied the Commissioner, with a touch of impatience. He was anxious to get on with the facts.

Sir Philip looked up, and for the first time Easton appeared to him as an individual. He was tall, with a soldierly moustache and bearing, but obviously unnerved by the distinguished company in which he found himself; the Home Secretary’s glance had somehow brought him to his feet, and under his gaze he shifted from one foot to the other, and with difficulty suppressed an almost irresistible inclination to salute.

“Pretty smart of you to get hold of a plan like this, Easton,” said Sir Philip encouragingly. “Where did you find it?”

“Mr. Mills gave it to me, sir—the secretary,” replied Easton. Something in Sir Philip’s manner seemed to have put him quite at his ease. During the rest of the interview he addressed himself to him exclusively, as though some mysterious bond of sympathy had been established between them. He even took a couple of paces towards the Home Secretary’s desk.

“Mr. Mills gave it to you, did he?” said the Home Secretary. “Where did he get it from? People don’t as a rule have plans of their houses ready to hand like that.”

“It’s a rough tracing of a plan of the drains, really, sir,” Easton explained gravely, “with the drains left out and a few other things put in. Mr. Mills told me that a new system of drainage had recently been put in at Hursley Lodge, and the builder left a plan behind in case any alterations were required.”

“I see. Very well, Easton. Tell me what you found when you got into the study.”

“It was a large room, sir, with a big bow-window on the south side. The frames were of the casement type, and were all wide open. There was very little furniture in the room, sir. A row of bookcases round the walls, and half a dozen chairs standing in front of them. One of them had been overturned, and was lying close inside the door leading into the hall. There were two other doors, sir. One led into the drawing-room, and was disguised as a bookcase. The bookcase swung open with the door, if you understand me, sir.”

Sir Philip nodded. “And the third door?” he asked.