По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

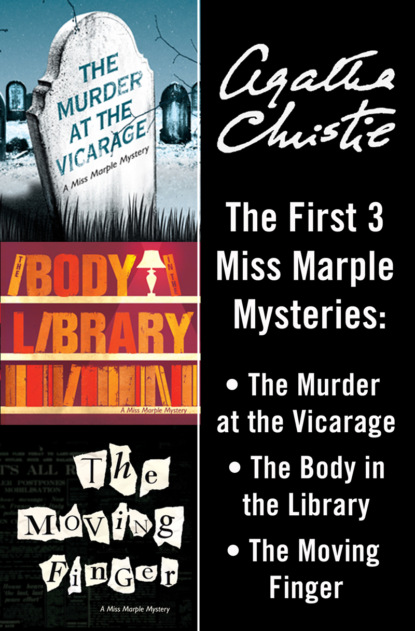

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Why?’

‘Because your job deals very largely with what we call right and wrong – and I’m not at all sure that there’s any such thing. Suppose it’s all a question of glandular secretion. Too much of one gland, too little of another – and you get your murderer, your thief, your habitual criminal. Clement, I believe the time will come when we’ll be horrified to think of the long centuries in which we’ve punished people for disease – which they can’t help, poor devils. You don’t hang a man for having tuberculosis.’

‘He isn’t dangerous to the community.’

‘In a sense he is. He infects other people. Or take a man who fancies he’s the Emperor of China. You don’t say how wicked of him. I take your point about the community. The community must be protected. Shut up these people where they can’t do any harm – even put them peacefully out of the way – yes, I’d go as far as that. But don’t call it punishment. Don’t bring shame on them and their innocent families.’

I looked at him curiously.

‘I’ve never heard you speak like this before.’

‘I don’t usually air my theories abroad. Today I’m riding my hobby. You’re an intelligent man, Clement, which is more than some parsons are. You won’t admit, I dare say, that there’s no such thing as what is technically termed, “Sin,” but you’re broadminded enough to consider the possibility of such a thing.’

‘It strikes at the root of all accepted ideas,’ he said.

‘Yes, we’re a narrow-minded, self-righteous lot, only too keen to judge matters we know nothing about. I honestly believe crime is a case for the doctor, not the policeman and not the parson. In the future, perhaps, there won’t be any such thing.’

‘You’ll have cured it?’

‘We’ll have cured it. Rather a wonderful thought. Have you ever studied the statistics of crime? No – very few people have. I have, though. You’d be amazed at the amount there is of adolescent crime, glands again, you see. Young Neil, the Oxfordshire murderer – killed five little girls before he was suspected. Nice lad – never given any trouble of any kind. Lily Rose, the little Cornish girl – killed her uncle because he docked her of sweets. Hit him when he was asleep with a coal hammer. Went home and a fortnight later killed her elder sister who had annoyed her about some trifling matter. Neither of them hanged, of course. Sent to a home. May be all right later – may not. Doubt if the girl will. The only thing she cares about is seeing the pigs killed. Do you know when suicide is commonest? Fifteen to sixteen years of age. From self-murder to murder of someone else isn’t a very long step. But it’s not a moral lack – it’s a physical one.’

‘What you say is terrible!’

‘No – it’s only new to you. New truths have to be faced. One’s ideas adjusted. But sometimes – it makes life difficult.’

He sat there, frowning, yet with a strange look of weariness.

‘Haydock,’ I said, ‘if you suspected – if you knew – that a certain person was a murderer, would you give that person up to the law, or would you be tempted to shield them?’

I was quite unprepared for the effect of my question. He turned on me angrily and suspiciously.

‘What makes you say that, Clement? What’s in your mind? Out with it, man.’

‘Why, nothing particular,’ I said, rather taken aback. ‘Only – well, murder is in our minds just now. If by any chance you happened to discover the truth – I wondered how you would feel about it, that was all.’

His anger died down. He stared once more straight ahead of him like a man trying to read the answer to a riddle that perplexes him, yet which exists only in his own brain.

‘If I suspected – if I knew – I should do my duty, Clement. At least, I hope so.’

‘The question is – which way would you consider your duty lay?’

He looked at me with inscrutable eyes.

‘That question comes to every man some time in his life, I suppose, Clement. And every man has to decide in his own way.’

‘You don’t know?’

‘No, I don’t know…’

I felt the best thing was to change the subject.

‘That nephew of mine is enjoying this case thoroughly,’ I said. ‘Spends his entire time looking for footprints and cigarette ash.’

Haydock smiled. ‘What age is he?’

‘Just sixteen. You don’t take tragedies seriously at that age. It’s all Sherlock Holmes and Arsene Lupin to you.’

Haydock said thoughtfully:

‘He’s a fine-looking boy. What are you going to do with him?’

‘I can’t afford a University education, I’m afraid. The boy himself wants to go into the Merchant Service. He failed for the Navy.’

‘Well – it’s a hard life – but he might do worse. Yes, he might do worse.’

‘I must be going,’ I exclaimed, catching sight of the clock. ‘I’m nearly half an hour late for lunch.’

My family were just sitting down when I arrived. They demanded a full account of the morning’s activities, which I gave them, feeling, as I did so, that most of it was in the nature of an anticlimax.

Dennis, however, was highly entertained by the history of Mrs Price Ridley’s telephone call, and went into fits of laughter as I enlarged upon the nervous shock her system had sustained and the necessity for reviving her with damson gin.

‘Serve the old cat right,’ he exclaimed. ‘She’s got the worst tongue in the place. I wish I’d thought of ringing her up and giving her a fright. I say, Uncle Len, what about giving her a second dose?’

I hastily begged him to do nothing of the sort. Nothing is more dangerous than the well-meant efforts of the younger generation to assist you and show their sympathy.

Dennis’s mood changed suddenly. He frowned and put on his man of the world air.

‘I’ve been with Lettice most of the morning,’ he said. ‘You know, Griselda, she’s really very worried. She doesn’t want to show it, but she is. Very worried indeed.’

‘I should hope so,’ said Griselda, with a toss of her head.

Griselda is not too fond of Lettice Protheroe.

‘I don’t think you’re ever quite fair to Lettice.’

‘Don’t you?’ said Griselda.

‘Lots of people don’t wear mourning.’

Griselda was silent and so was I. Dennis continued:

‘She doesn’t talk to most people, but she does talk to me. She’s awfully worried about the whole thing, and she thinks something ought to be done about it.’

‘She will find,’ I said, ‘that Inspector Slack shares her opinion. He is going up to Old Hall this afternoon, and will probably make the life of everybody there quite unbearable to them in his efforts to get at the truth.’

‘What do you think is the truth, Len?’ asked my wife suddenly.

‘It’s hard to say, my dear. I can’t say that at the moment I’ve any idea at all.’