По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

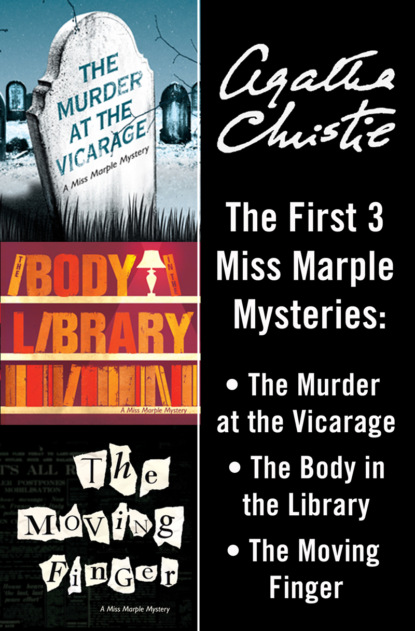

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘But you are going to do so?’

I was silent. I dislike hounding a man down who has already got the forces of law and order against him. I held no brief for Archer. He is an inveterate poacher – one of those cheerful ne’er-do-weels that are to be found in any parish. Whatever he may have said in the heat of anger when he was sentenced I had no definite knowledge that he felt the same when he came out of prison.

‘You heard the conversation,’ I said at last. ‘If you feel it your duty to go to the police with it, you must do so.’

‘It would come better from you, sir.’

‘Perhaps – but to tell the truth – well, I’ve no fancy for doing it. I might be helping to put the rope round the neck of an innocent man.’

‘But if he shot Colonel Protheroe –’

‘Oh, if! There’s no evidence of any kind that he did.’

‘His threats.’

‘Strictly speaking, the threats were not his, but Colonel Protheroe’s. Colonel Protheroe was threatening to show Archer what vengeance was worth next time he caught him.’

‘I don’t understand your attitude, sir.’

‘Don’t you,’ I said wearily. ‘You’re a young man. You’re zealous in the cause of right. When you get to my age, you’ll find that you like to give people the benefit of the doubt.’

‘It’s not – I mean –’

He paused, and I looked at him in surprise.

‘You haven’t any – any idea of your own – as to the identity of the murderer, I mean?’

‘Good heavens, no.’

Hawes persisted. ‘Or as to the – motive?’

‘No. Have you?’

‘I? No, indeed. I just wondered. If Colonel Protheroe had – had confided in you in any way – mentioned anything…’

‘His confidences, such as they were, were heard by the whole village street yesterday morning,’ I said dryly.

‘Yes. Yes, of course. And you don’t think – about Archer?’

‘The police will know all about Archer soon enough,’ I said. ‘If I’d heard him threaten Colonel Protheroe myself, that would be a different matter. But you may be sure that if he actually has threatened him, half the people in the village will have heard him, and the news will get to the police all right. You, of course, must do as you like about the matter.’

But Hawes seemed curiously unwilling to do anything himself.

The man’s whole attitude was nervous and queer. I recalled what Haydock had said about his illness. There, I supposed, lay the explanation.

He took his leave unwillingly, as though he had more to say, and didn’t know how to say it.

Before he left, I arranged with him to take the service for the Mothers’ Union, followed by the meeting of District Visitors. I had several projects of my own for the afternoon.

Dismissing Hawes and his troubles from my mind I started off for Mrs Lestrange.

On the table in the hall lay the Guardian and the Church Times unopened.

As I walked, I remembered that Mrs Lestrange had had an interview with Colonel Protheroe the night before his death. It was possible that something had transpired in that interview which would throw light upon the problem of his murder.

I was shown straight into the little drawing-room, and Mrs Lestrange rose to meet me. I was struck anew by the marvellous atmosphere that this woman could create. She wore a dress of some dead black material that showed off the extraordinary fairness of her skin. There was something curiously dead about her face. Only the eyes were burningly alive. There was a watchful look in them today. Otherwise she showed no signs of animation.

‘It was very good of you to come, Mr Clement,’ she said, as she shook hands. ‘I wanted to speak to you the other day. Then I decided not to do so. I was wrong.’

‘As I told you then, I shall be glad to do anything that can help you.’

‘Yes, you said that. And you said it as though you meant it. Very few people, Mr Clement, in this world have ever sincerely wished to help me.’

‘I can hardly believe that, Mrs Lestrange.’

‘It is true. Most people – most men, at any rate, are out for their own hand.’ There was a bitterness in her voice.

I did not answer, and she went on:

‘Sit down, won’t you?’

I obeyed, and she took a chair facing me. She hesitated a moment and then began to speak very slowly and thoughtfully, seeming to weigh each word as she uttered it.

‘I am in a very peculiar position, Mr Clement, and I want to ask your advice. That is, I want to ask your advice as to what I should do next. What is past is past and cannot be undone. You understand?’

Before I could reply, the maid who had admitted me opened the door and said with a scared face:

‘Oh! Please, ma’am, there is a police inspector here, and he says he must speak to you, please.’

There was a pause. Mrs Lestrange’s face did not change. Only her eyes very slowly closed and opened again. She seemed to swallow once or twice, then she said in exactly the same clear, calm voice: ‘Show him in, Hilda.’

I was about to rise, but she motioned me back again with an imperious hand.

‘If you do not mind – I should be much obliged if you would stay.’

I resumed my seat.

‘Certainly, if you wish it,’ I murmured, as Slack entered with a brisk regulation tread.

‘Good afternoon, madam,’ he began.

‘Good afternoon, Inspector.’

At this moment, he caught sight of me and scowled. There is no doubt about it, Slack does not like me.

‘You have no objection to the Vicar’s presence, I hope?’

I suppose that Slack could not very well say he had.