По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

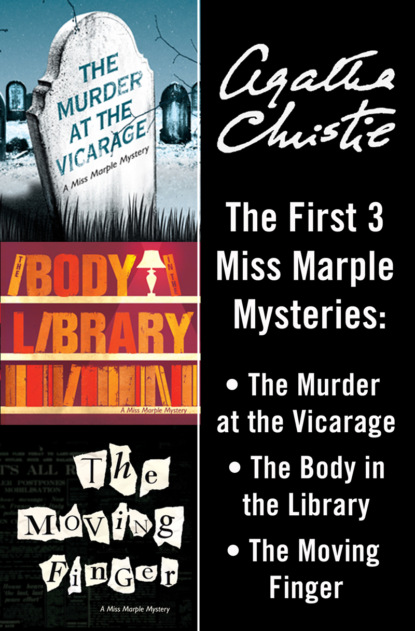

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No-o,’ he said grudgingly. ‘Though, perhaps, it might be better –’

Mrs Lestrange paid no attention to the hint.

‘What can I do for you, Inspector?’ she asked.

‘It’s this way, madam. Murder of Colonel Protheroe. I’m in charge of the case and making inquiries.’

Mrs Lestrange nodded.

‘Just as a matter of form, I’m asking every one just where they were yesterday evening between the hours of 6 and 7 p.m. Just as a matter of form, you understand.’

‘You want to know where I was yesterday evening between six and seven?’

‘If you please, madam.’

‘Let me see.’ She reflected a moment. ‘I was here. In this house.’

‘Oh!’ I saw the Inspector’s eyes flash. ‘And your maid – you have only one maid, I think – can confirm that statement?’

‘No, it was Hilda’s afternoon out.’

‘I see.’

‘So, unfortunately, you will have to take my word for it,’ said Mrs Lestrange pleasantly.

‘You seriously declare that you were at home all the afternoon?’

‘You said between six and seven, Inspector. I was out for a walk early in the afternoon. I returned some time before five o’clock.’

‘Then if a lady – Miss Hartnell, for instance – were to declare that she came here about six o’clock, rang the bell, but could make no one hear and was compelled to go away again – you’d say she was mistaken, eh?’

‘Oh, no,’ Mrs Lestrange shook her head.

‘But –’

‘If your maid is in, she can say not at home. If one is alone and does not happen to want to see callers – well, the only thing to do is to let them ring.’

Inspector Slack looked slightly baffled.

‘Elderly women bore me dreadfully,’ said Mrs Lestrange. ‘And Miss Hartnell is particularly boring. She must have rung at least half a dozen times before she went away.’

She smiled sweetly at Inspector Slack.

The Inspector shifted his ground.

‘Then if anyone were to say they’d seen you out and about then –’

‘Oh! but they didn’t, did they?’ She was quick to sense his weak point. ‘No one saw me out, because I was in, you see.’

‘Quite so, madam.’

The Inspector hitched his chair a little nearer.

‘Now I understand, Mrs Lestrange, that you paid a visit to Colonel Protheroe at Old Hall the night before his death.’

Mrs Lestrange said calmly: ‘That is so.’

‘Can you indicate to me the nature of that interview?’

‘It concerned a private matter, Inspector.’

‘I’m afraid I must ask you tell me the nature of that private matter.’

‘I shall not tell you anything of the kind. I will only assure you that nothing which was said at that interview could possibly have any bearing upon the crime.’

‘I don’t think you are the best judge of that.’

‘At any rate, you will have to take my word for it, Inspector.’

‘In fact, I have to take your word about everything.’

‘It does seem rather like it,’ she agreed, still with the same smiling calm.

Inspector Slack grew very red.

‘This is a serious matter, Mrs Lestrange. I want the truth –’ He banged his fist down on a table. ‘And I mean to get it.’

Mrs Lestrange said nothing at all.

‘Don’t you see, madam, that you’re putting yourself in a very fishy position?’

Still Mrs Lestrange said nothing.

‘You’ll be required to give evidence at the inquest.’

‘Yes.’

Just the monosyllable. Unemphatic, uninterested. The Inspector altered his tactics.

‘You were acquainted with Colonel Protheroe?’

‘Yes, I was acquainted with him.’

‘Well acquainted?’

There was a pause before she said:

‘I had not seen him for several years.’