По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

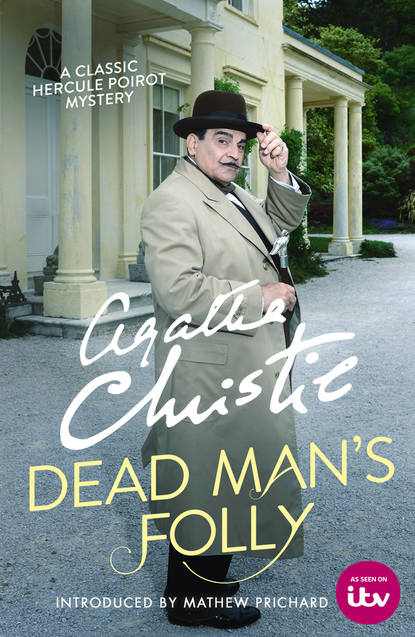

Dead Man’s Folly

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘George,’ said Mrs Folliat, ‘this is M. Poirot who is so kind as to come and help us. Sir George Stubbs.’

Sir George, who had been talking in a loud voice, swung round. He was a big man with a rather florid red face and a slightly unexpected beard. It gave a rather disconcerting effect of an actor who had not quite made up his mind whether he was playing the part of a country squire, or of a ‘rough diamond’ from the Dominions. It certainly did not suggest the navy, in spite of Michael Weyman’s remarks. His manner and voice were jovial, but his eyes were small and shrewd, of a particularly penetrating pale blue.

He greeted Poirot heartily.

‘We’re so glad that your friend Mrs Oliver managed to persuade you to come,’ he said. ‘Quite a brain-wave on her part. You’ll be an enormous attraction.’

He looked round a little vaguely.

‘Hattie?’ He repeated the name in a slightly sharper tone. ‘Hattie!’

Lady Stubbs was reclining in a big arm-chair a little distance from the others. She seemed to be paying no attention to what was going on round her. Instead she was smiling down at her hand which was stretched out on the arm of the chair. She was turning it from left to right, so that a big solitaire emerald on her third finger caught the light in its green depths.

She looked up now in a slightly startled childlike way and said, ‘How do you do.’

Poirot bowed over her hand.

Sir George continued his introductions.

‘Mrs Masterton.’

Mrs Masterton was a somewhat monumental woman who reminded Poirot faintly of a bloodhound. She had a full underhung jaw and large, mournful, slightly blood-shot eyes.

She bowed and resumed her discourse in a deep voice which again made Poirot think of a bloodhound’s baying note.

‘This silly dispute about the tea tent has got to be settled, Jim,’ she said forcefully. ‘They’ve got to see sense about it. We can’t have the whole show a fiasco because of these idiotic women’s local feuds.’

‘Oh, quite,’ said the man addressed.

‘Captain Warburton,’ said Sir George.

Captain Warburton, who wore a check sports coat and had a vaguely horsy appearance, showed a lot of white teeth in a somewhat wolfish smile, then continued his conversation.

‘Don’t you worry, I’ll settle it,’ he said. ‘I’ll go and talk to them like a Dutch uncle. What about the fortune-telling tent? In the space by the magnolia? Or at the far end of the lawn by the rhododendrons?’

Sir George continued his introductions.

‘Mr and Mrs Legge.’

A tall young man with his face peeling badly from sunburn grinned agreeably. His wife, an attractive freckled redhead, nodded in a friendly fashion, then plunged into controversy with Mrs Masterton, her agreeable high treble making a kind of duet with Mrs Masterton’s deep bay.

‘– not by the magnolia – a bottle-neck –’

‘– one wants to disperse things – but if there’s a queue –’

‘– much cooler. I mean, with the sun full on the house –’

‘– and the coconut shy can’t be too near the house – the boys are so wild when they throw –’

‘And this,’ said Sir George, ‘is Miss Brewis – who runs us all.’

Miss Brewis was seated behind the large silver tea tray.

She was a spare efficient-looking woman of forty-odd, with a brisk pleasant manner.

‘How do you do, M. Poirot,’ she said. ‘I do hope you didn’t have too crowded a journey? The trains are sometimes too terrible this time of year. Let me give you some tea. Milk? Sugar?’

‘Very little milk, mademoiselle, and four lumps of sugar.’ He added, as Miss Brewis dealt with his request, ‘I see that you are all in a great state of activity.’

‘Yes, indeed. There are always so many last-minute things to see to. And people let one down in the most extraordinary way nowadays. Over marquees, and tents and chairs and catering equipment. One has to keep on at them. I was on the telephone half the morning.’

‘What about these pegs, Amanda?’ said Sir George. ‘And the extra putters for the clock golf ?’

‘That’s all arranged, Sir George. Mr Benson at the golf club was most kind.’

She handed Poirot his cup.

‘A sandwich, M. Poirot? Those are tomato and these are paté. But perhaps,’ said Miss Brewis, thinking of the four lumps of sugar, ‘you would rather have a cream cake?’

Poirot would rather have a cream cake, and helped himself to a particularly sweet and squelchy one.

Then, balancing it carefully on his saucer, he went and sat down by his hostess. She was still letting the light play over the jewel on her hand, and she looked up at him with a pleased child’s smile.

‘Look,’ she said. ‘It’s pretty, isn’t it?’

He had been studying her carefully. She was wearing a big coolie-style hat of vivid magenta straw. Beneath it her face showed its pinky reflection on the dead-white surface of her skin. She was heavily made up in an exotic un-English style. Dead-white matt skin; vivid cyclamen lips, mascara applied lavishly to the eyes. Her hair showed beneath the hat, black and smooth, fitting like a velvet cap. There was a languorous un-English beauty about the face. She was a creature of the tropical sun, caught, as it were, by chance in an English drawing-room. But it was the eyes that startled Poirot. They had a childlike, almost vacant, stare.

She had asked her question in a confidential childish way, and it was as though to a child that Poirot answered.

‘It is a very lovely ring,’ he said.

She looked pleased.

‘George gave it to me yesterday,’ she said, dropping her voice as though she were sharing a secret with him. ‘He gives me lots of things. He’s very kind.’

Poirot looked down at the ring again and the hand outstretched on the side of the chair. The nails were very long and varnished a deep puce.

Into his mind a quotation came: ‘They toil not, neither do they spin…’

He certainly couldn’t imagine Lady Stubbs toiling or spinning. And yet he would hardly have described her as a lily of the field. She was a far more artificial product.

‘This is a beautiful room you have here, Madame,’ he said, looking round appreciatively.

‘I suppose it is,’ said Lady Stubbs vaguely.

Her attention was still on her ring; her head on one side, she watched the green fire in its depths as her hand moved.

She said in a confidential whisper, ‘D’you see? It’s winking at me.’