По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

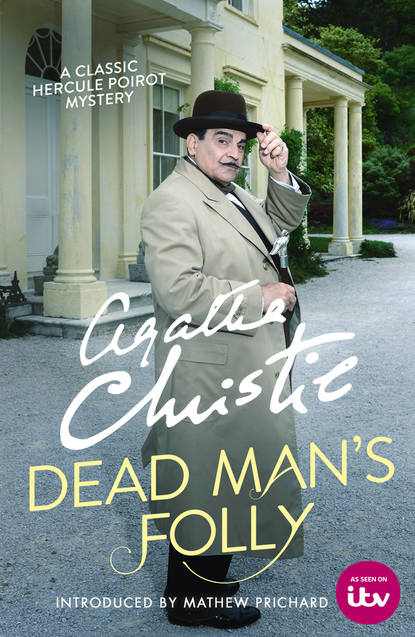

Dead Man’s Folly

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Which just shows you what fools women are!’

‘It shows you what people are. It is, perhaps, that absorption in one’s personal life that has led the human race to survive.’

Alec Legge gave a scornful laugh.

‘Sometimes,’ he said, ‘I think it’s a pity they ever did.’

‘It is, you know,’ Poirot persisted, ‘a form of humility. And humility is valuable. There was a slogan that was written up in your underground railways here, I remember, during the war. “It all depends on you.” It was composed, I think, by some eminent divine – but in my opinion it was a dangerous and undesirable doctrine. For it is not true. Everything does not depend on, say, Mrs Blank of Little-Blank-in-the-Marsh. And if she is led to think it does, it will not be good for her character. While she thinks of the part she can play in world affairs, the baby pulls over the kettle.’

‘You are rather old-fashioned in your views, I think. Let’s hear what your slogan would be.’

‘I do not need to formulate one of my own. There is an older one in this country which contents me very well.’

‘What is that?’

‘“Put your trust in God, and keep your powder dry.”’

‘Well, well…’ Alec Legge seemed amused. ‘Most unexpected coming from you. Do you know what I should like to see done in this country?’

‘Something, no doubt, forceful and unpleasant,’ said Poirot, smiling.

Alec Legge remained serious.

‘I should like to see every feeble-minded person put out – right out! Don’t let them breed. If, for one generation, only the intelligent were allowed to breed, think what the result would be.’

‘A very large increase of patients in the psychiatric wards, perhaps,’ said Poirot dryly. ‘One needs roots as well as flowers on a plant, Mr Legge. However large and beautiful the flowers, if the earthy roots are destroyed there will be no more flowers.’ He added in a conversational tone: ‘Would you consider Lady Stubbs a candidate for the lethal chamber?’

‘Yes, indeed. What’s the good of a woman like that? What contribution has she ever made to society? Has she ever had an idea in her head that wasn’t of clothes or furs or jewels? As I say, what good is she?’

‘You and I,’ said Poirot blandly, ‘are certainly much more intelligent than Lady Stubbs. But’ – he shook his head sadly – ‘it is true, I fear, that we are not nearly so ornamental.’

‘Ornamental…’ Alec was beginning with a fierce snort, but he was interrupted by the re-entry of Mrs Oliver and Captain Warburton through the window.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_1d25b4eb-9f62-5085-845d-6f54105adc8e)

‘You must come and see the clues and things for the Murder Hunt, M. Poirot,’ said Mrs Oliver breathlessly.

Poirot rose and followed them obediently.

The three of them went across the hall and into a small room furnished plainly as a business office.

‘Lethal weapons to your left,’ observed Captain Warburton, waving his hand towards a small baize-covered card table. On it were laid out a small pistol, a piece of lead piping with a rusty sinister stain on it, a blue bottle labelled Poison, a length of clothes line and a hypodermic syringe.

‘Those are the Weapons,’ explained Mrs Oliver, ‘and these are the Suspects.’

She handed him a printed card which he read with interest.

Suspects

Poirot blinked and looked towards Mrs Oliver in mute incomprehension.

‘A magnificent Cast of Characters,’ he said politely. ‘But permit me to ask, Madame, what does the Competitor do?’

‘Turn the card over,’ said Captain Warburton.

Poirot did so.

On the other side was printed:

Name and address .….….….….….………

Solution:

Name of Murderer:….….….….….………

Weapon:….….….….….….….………

Motive:….….….….….….….….

Time and Place:….….….….….…..

Reasons for arriving at your conclusions:.….…..….….….….….….….….….…..

‘Everyone who enters gets one of these,’ explained Captain Warburton rapidly. ‘Also a notebook and pencil for copying clues. There will be six clues. You go on from one to the other like a Treasure Hunt, and the weapons are concealed in suspicious places. Here’s the first clue. A snapshot. Everyone starts with one of these.’

Poirot took the small print from him and studied it with a frown. Then he turned it upside down. He still looked puzzled. Warburton laughed.

‘Ingenious bit of trick photography, isn’t it?’ he said complacently. ‘Quite simple once you know what it is.’

Poirot, who did not know what it was, felt a mounting annoyance.

‘Some kind of barred window?’ he suggested.

‘Looks a bit like it, I admit. No, it’s a section of a tennis net.’

‘Ah.’ Poirot looked again at the snapshot. ‘Yes, it is as you say – quite obvious when you have been told what it is!’

‘So much depends on how you look at a thing,’ laughed Warburton.

‘That is a very profound truth.’

‘The second clue will be found in a box under the centre of the tennis net. In the box are this empty poison bottle – here, and a loose cork.’

‘Only, you see,’ said Mrs Oliver rapidly, ‘it’s a screw-topped bottle, so the cork is really the clue.’

‘I know, Madame, that you are always full of ingenuity, but I do not quite see –’

Mrs Oliver interrupted him.