По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

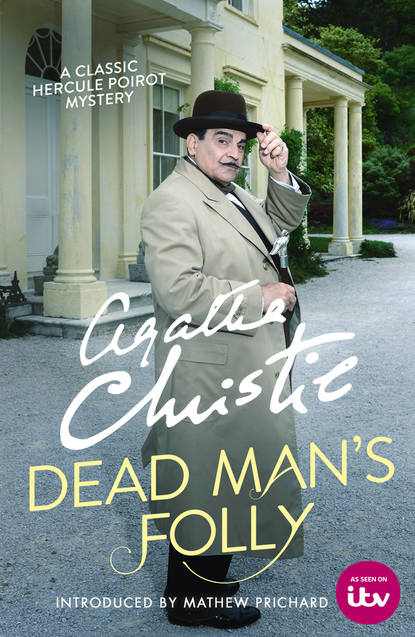

Dead Man’s Folly

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Look here, Jim,’ she said, ‘you’ve got to be on my side. That tent’s got to be where we all decided – on the far side of the lawn backing on the rhododendrons. It’s the only possible place.’

‘Ma Masterton doesn’t think so.’

‘Well, you’ve got to talk her out of it.’

He gave her his foxy smile.

‘Mrs Masterton’s my boss.’

‘Wilfred Masterton’s your boss. He’s the M.P.’

‘I dare say, but she should be. She’s the one who wears the pants – and don’t I know it.’

Sir George re-entered the window.

‘Oh, there you are, Sally,’ he said. ‘We need you. You wouldn’t think everyone could get het up over who butters the buns and who raffles a cake, and why the garden produce stall is where the fancy woollens was promised it should be. Where’s Amy Folliat? She can deal with these people – about the only person who can.’

‘She went upstairs with Hattie.’

‘Oh, did she –?’

Sir George looked round in a vaguely helpless manner and Miss Brewis jumped up from where she was writing tickets, and said, ‘I’ll fetch her for you, Sir George.’

‘Thank you, Amanda.’

Miss Brewis went out of the room.

‘Must get hold of some more wire fencing,’ murmured Sir George.

‘For the fête?’

‘No, no. To put up where we adjoin Hoodown Park in the woods. The old stuff’s rotted away, and that’s where they get through.’

‘Who get through?’

‘Trespassers!’ ejaculated Sir George.

Sally Legge said amusedly:

‘You sound like Betsy Trotwood campaigning against donkeys.’

‘Betsy Trotwood? Who’s she?’ asked Sir George simply.

‘Dickens.’

‘Oh, Dickens. I read the Pickwick Papers once. Not bad. Not bad at all – surprised me. But, seriously, trespassers are a menace since they’ve started this Youth Hostel tomfoolery. They come out at you from everywhere wearing the most incredible shirts – boy this morning had one all covered with crawling turtles and things – made me think I’d been hitting the bottle or something. Half of them can’t speak English – just gibber at you…’ He mimicked: ‘“Oh, plees – yes, haf you – tell me – iss way to ferry?” I say no, it isn’t, roar at them, and send them back where they’ve come from, but half the time they just blink and stare and don’t understand. And the girls giggle. All kinds of nationalities, Italian, Yugoslavian, Dutch, Finnish – Eskimos I shouldn’t be surprised! Half of them communists, I shouldn’t wonder,’ he ended darkly.

‘Come now, George, don’t get started on communists,’ said Mrs Legge. ‘I’ll come and help you deal with the rabid women.’

She led him out of the window and called over her shoulder: ‘Come on, Jim. Come and be torn to pieces in a good cause.’

‘All right, but I want to put M. Poirot in the picture about the Murder Hunt since he’s going to present the prizes.’

‘You can do that presently.’

‘I will await you here,’ said Poirot agreeably.

In the ensuing silence, Alec Legge stretched himself out in his chair and sighed.

‘Women!’ he said. ‘Like a swarm of bees.’

He turned his head to look out of the window.

‘And what’s it all about? Some silly garden fête that doesn’t matter to anyone.’

‘But obviously,’ Poirot pointed out, ‘there are those to whom it does matter.’

‘Why can’t people have some sense? Why can’t they think? Think of the mess the whole world has got itself into. Don’t they realize that the inhabitants of the globe are busy committing suicide?’

Poirot judged rightly that he was not intended to reply to this question. He merely shook his head doubtfully.

‘Unless we can do something before it’s too late…’ Alec Legge broke off. An angry look swept over his face. ‘Oh, yes,’ he said, ‘I know what you’re thinking. That I’m nervy, neurotic – all the rest of it. Like those damned doctors. Advising rest and change and sea air. All right, Sally and I came down here and took the Mill Cottage for three months, and I’ve followed their prescription. I’ve fished and bathed and taken long walks and sun-bathed –’

‘I noticed that you had sunbathed, yes,’ said Poirot politely.

‘Oh, this?’ Alec’s hand went to his sore face. ‘That’s the result of a fine English summer for once in a way. But what’s the good of it all? You can’t get away from facing truth just by running away from it.’

‘No, it is never any good running away.’

‘And being in a rural atmosphere like this just makes you realize things more keenly – that and the incredible apathy of the people of this country. Even Sally, who’s intelligent enough, is just the same. Why bother? That’s what she says. It makes me mad! Why bother?’

‘As a matter of interest, why do you?’

‘Good God, you too?’

‘No, it is not advice. It is just that I would like to know your answer.’

‘Don’t you see, somebody’s got to do something.’

‘And that somebody is you?’

‘No, no, not me personally. One can’t be personal in times like these.’

‘I do not see why not. Even in “these times” as you call it, one is still a person.’

‘But one shouldn’t be! In times of stress, when it’s a matter of life or death, one can’t think of one’s own insignificant ills or preoccupations.’

‘I assure you, you are quite wrong. In the late war, during a severe air-raid, I was much less preoccupied by the thought of death than of the pain from a corn on my little toe. It surprised me at the time that it should be so. “Think,” I said to myself, “at any moment now, death may come.” But I was still conscious of my corn – indeed, I felt injured that I should have that to suffer as well as the fear of death. It was because I might die that every small personal matter in my life acquired increased importance. I have seen a woman knocked down in a street accident, with a broken leg, and she has burst out crying because she sees that there is a ladder in her stocking.’